Revolt brewing across Europe? Don’t get out your pitchforks and torches just yet

Where does resistance to austerity in Europe stand, four years into the crisis? Journalist Leigh Phillips, until recently based in Brussels, where he reported for the EUobserver and the Guardian, assesses the situation and identifies four priorities for a progressive anti-austerity movement in Europe.

Last spring, as EU finance ministers met at the Godollo Palace just outside the Hungarian capital to agree on the imposition of a bail-out on a recalcitrant Portugal, a boisterous anti-austerity demonstration - the largest labour protest in the country in 20 years - filled the streets of Budapest. A local reporter managing to buttonhole Swedish finance minister Anders Borg pressed the ponytail-and-earring-sporting conservative whether the scale of the protest would have any impact on their deliberations.

He chuckled at such a ludicrous question. The journalist might as well have asked whether the stodginess of the sour-cream-paprika-and-lard-laden Hungarian cuisine would have any impact on austerity discussions.

“They’re unions. Isn’t that what they do?” he responded before moving onto more serious inquiries.

The incident, though inconsequential in itself, was for this reporter emblematic of European elite deafness to the anger of the street.

However many general strikes - and there have been dozens now - however rambunctious the protest, they simply could not care less. There was plainly nothing the popular classes could do, no act of disobedience, that matched the vertiginous scale of economic destruction both threatened and being wrought by the markets.

“How quaint, you with your placards and banners and marches,” seemed to be the feeling. “You know that we could be days away from the destruction of the single currency, or even the EU? A single report from a rating agency is more frightening than three million of you in the streets. What can you possibly do that compares to that? Nothing? Okay, well, thanks for popping by. We’ll just continue with the regularly scheduled programme.”

A year later however, elites appear more shaken, at least rhetorically. In October last year, Europe experienced something of a deja vu when in the space of a week, both the German chancellor and the Polish finance minister warned of war if the crisis is not rapidly resolved.

And this spring, events in France, the Netherlands and the Czech Republic, have convinced a range of commentators are convinced that the EU is experiencing an angry anti-austerity backlash and even “crisis of legitimacy”.

France’s president, Nicholas Sarkozy looks set to be toppled against a background of the highest ever levels of support for the far-right Front National and a record score for the far left. Right-wing Dutch Prime Minister Mark Rutte on Monday resigned after the hard-right Freedom Party withdrew its support for the government over opposition to austerity measures. And the Czech Republic was rocked by the biggest protest since the end of Communism on Saturday and its government too will likely tumble too, come a confidence vote on Friday, with austerity a prime factor in the downfall.

This all comes just a month after the conservative Slovak administration was turfed out by the centre-left, and weeks ahead of an Irish referendum on yet another European treaty that will likely see the document receive a drubbing from the natives of this EU vassal state. Greek elections meanwhile on 6 May will likely return a majority of anti-EU deputies in a variety of far-left, far-right and other “fringe” flavourings.

“Today’s reality is that the financial crash, whatever its origins, is stirring a potentially far-reaching crisis of legitimacy in Europe’s political system,” wrote the Financial Times’ Tony Barber in a variation on a theme of analysis repeated across Europe and indeed across the Atlantic.

With respect to France and the votes for Marine Le Pen and Jean-Luc Melenchon, Barber added: “Almost one in three voters backed this pair of extremists in spite of their doltish proposals for tackling the financial crisis.”

Others have described a revolt at the ballot box and in the street, a “backlash” (CNN, New York Times) that has gained “a critical mass” (Guardian), the “rise of populism”, a “crisis of legitimacy” for European elites. Deutsche Welle clamoured: “Crisis topples governments like dominos”. The future battles of European politics, they have discovered, will increasingly be fought between a sensible, rational, pragmatic centre (however cackhanded they may be in their messaging explaining the “necessary measures”) and a conflation of the radical left and far right extremism.

“Governments have fallen, more are at risk and in some places, a stark streak of nationalism is on the rise that could swing Europe ever deeper into a fortress mentality,” the German international broadcaster shrieked, noting that only Malta, Austria, Luxembourg and Germany had not seen a change of government since the onset of the crisis. “These states are the last refuges of stability.”

Conversely, some of these same pundits also see in France, Slovakia, the Czech Republic, as with Denmark and Ireland a revival in social democracy’s fortunes after years of Christian Democrat and conservative domination in Europe. The FTD’s Wolfgang Munchau cheered the likely victory of Hollande in France as the beginning of a “progressive insurrection” that will challenge the Merkel consensus and counteract the rise of “political extremism”.

Something is certainly stirring, but it is worthwhile going beyond what in these articles amounts to little more than the application of the methodology of fashion reporters to the field of politics - a breathless trend-spotting that is barren of evidence - never mind the barely concealed elite-sympathising received wisdom of these keyboard warriors.

Four years into the crisis, it is a good time for a sober, frank exploration of the state of play of resistance to austerity. And the events of the last few weeks provide a useful jumping-off point for assessing the current conjuncture.

Can we say, as these commentators have suggested, that a revolt is brewing?

The significance of Hollande, Melechon and Le Pen

The key lesson to draw from the first-round victory of Socialist Party presidential candidate Francois Hollande is that this is in no way represents a bloody nose for the ideologues of austerity.

It is important to understand that within the European Commission, between the EU and the IMF, between the German chancellor and her finance minister, within the European Council, there is a rainbow of what could be described as austerity perspectives, not a single programme on which everyone is united, and that this variety of positions is dynamic, changing from month to month. Washington, for example, has consistently been less disciplinarian on the question of debt repayment than Brussels.

While Hollande’s voters may have been expressing their opposition to austerity and the EU’s undermining of national sovereignty, and it is noteworthy that Hollande felt confident enough to make opposition to European austerity central to his campaign, he himself actually lies within this European austerity spectrum, not outside it.

Above all, while he certainly rattled markets by threatening to refuse to ratify the EU Fiscal Treaty. if his demands are not met, he represents absolutely no threat to the document.

Within hours of the first-round vote, his policy chief Michel Sapin, a former finance minister, picked the Financial Times as the venue to issue his boss’s assurances that the treaty is not in any peril should Hollande win the second round.

“What concerns us is not what is in the treaty, it is what is not in the treaty,” Sapin told the reporter. “[Hollande] is not saying we must renegotiate the budgetary discipline.”

The unprecedented transfer of fiscal sovereignty to unelected institutions, the effective removal of spending decisions from the realm of democratic chambers, represented in the European ‘Economic Governance’ strategy, will not be opposed. This is what Hollande, the champion of French sovereignty, has just said.

Rather, Hollande is looking for an “addition to the treaty to inject measures to boost growth”.

It remains to be seen explicitly what he would want, but in advance of more details, we can say that ‘growth measures’ of a certain type are an amplification of the austerity doctrine, not its antithesis. The aforementioned Swedish finance minister - who despite his nation being outside the eurozone, has been an eloquent cat’s paw for Berlin - described this position to the German Marshall Fund in February: “Growth-enhancing measures is not about stimulating demand. It is about releasing growth through structural reforms, particularly when it comes to regulatory barriers to entry in domestic service sectors.”

Privatisation of public services and labour market reform: these are thus what is understood within EU orthodoxy as the ‘growth’ complement to austerity. Given the enthusiasm for both by other social democratic leaders in Europe, in particular Jose Luis Zapatero, late of Spain, it is certainly conceivable that a President Hollande would be comfortable with this as well.

It is also sensible to be wary of some of the false opponents of austerity, such as former US Treasury secretary under Bill Clinton Larry Summers, who is emblematic of this tendency, who argues that austerity at the moment is counterproductive, but that “phased in, commitments in these areas would be constructive.”

“There will ultimately be a need to raise retirement ages, reform sclerosis-inducing regulations and restructure benefit programmes,” he writes.

Many in Brussels and Frankfurt have been able to calm their worst fears of the prospect of an Hollande victory by reminding themselves that neo-liberal reforms have frequently been more likely to be delivered by the left than the right and that the French Socialist may actually succeed in scaling back public expenditure and weakening labour protections where Sarkozy failed.

So if Summers’ thinking is representative of the sort of ideas at the heart of Hollande’s “progressive insurrection” against austerity, certainly, the Socialist candidate will not be a voice within the European Council pressing for a fresh “Keynesian injection of public funds into the economy,” according, again, to Sapin.

Instead, he will be satisfied with additions to the treaty to inject measures to boost growth. This involves not the issuance of EU-level bonds, but the creation of EU ‘project bonds’ “not to finance [sovereign] debt but to finance projects, for example in the development of new-energy technology.” The idea of European project bonds has already been proposed by the European Commission, so this item is very far from the heterodox.

According to German sources, Berlin has already prepared itself for demands for amendments to the fiscal treaty, but are expecting financial markets to quickly discipline Hollande should he stray too far from what concessions Merkel can accept.

Hollande’s man says that he will not be assuaged by “cosmetic changes” to the fiscal treaty, but that is precisely what is most likely to happen.

On the question of the role of the European Central Bank, Sapin continued to put Frankfurt at ease: “[Mr Hollande] never has and is not calling into question the independence of the ECB. He is not calling for a modification of the [ECB’s founding] treaty. What he says is that the ECB must take into account this issue of growth in Europe – it has already done so and it should do more.”

This is all very well. Politicians can say what they like about what the ECB should and should not be doing, but without any challenge to its independence from democratic control, this statement is empty of effect. It is also in any case identical to Sarkozy’s longstanding position on the central bank.

Hollande at best may represent an additional voice in the European Council pressing for a relaxation of austerity. Madrid’s conservative leader, Mariano Rajoy, in March, announced a softer budget target for 2012, from the original 4.4 percent to 5.8 percent, only to be quickly retreat in the face of hostility from Brussels and Berlin. Madrid would probably now have something of an ally in Paris. But this is the limit of what change can be expected.

Nevertheless, all of this is rather to be expected. Hollande is merely repeating the traditional social-democratic electoral calculus of the last two decades of campaigning to the left and governing from the right. Anyone who actually bore hopes that Hollande might be the man to inject some Keynesian reason to the monomaniacally neo-liberal discussions on the eurozone crisis cannot have been paying much attention to the social democratic experience.

What is unusual however is the degree to which his rhetoric at least could march off tangentially from the austerity consensus, giving such fright to the post-democratic architects of European economic governance in Brussels, Berlin and Frankfurt.

Around the world, there has been a qualitative change in what is permissible within the heavily policed borders of reasonable debate in the last year.

This is an enormous yet perhaps unrecognised victory.

Unrecognised as it has as yet led to very few if any concrete policy changes, but enormous because perhaps the greatest hurdle proponents of more progressive solutions to economic problems have faced for two decades is the near total ideological hegemony of neoclassicism, not merely at the official level, but via the ‘privatisation of our minds’. There Is No Alternative had ceased to be a Thatcherite mantra but become a Truth as true and ineluctable as gravity or a baby’s smile.

Globally, the likes of the Occupy movement, UK Uncut and the Indignados, however much they have been fairly or unfairly criticised for the incoherence of their demands, have stretched open a space where a genuinely oppositional, completely different vision of how society should be run can be placed on the table without all ‘right-thinking’ people laughing at the absurdity of the idea. There is still a shrill effort at declaiming what remain - however oppositional - fairly moderate reform proposals (When you compare for example, Melenchon’s tax proposals to what was standard practice by post-war governments left and right up till the 1970s, they do indeed appear decidedly moderate), as evidenced by the FT’s conflation of Melenchon and Le Pen as doltish twins of the extreme left and right. And this will get ever louder as heterodox economic ideas further gain favour. But there is a breach in the neoclassical dyke. And a big one.

This has been matched at the more ‘respectable’ level by the volume of mainstream criticism of the EU’s austerity policies in the pages of establishment publications given the scale of evidence that it simply is not working. Capital controls, even industrial policies cannot be the taboo they have been since the late eighties if even the World Bank has the confidence to dust off old textbooks on these subjects.

Domestically, this is the major significance of Melenchon phenomenon. However scary his ideas may have been to Medef, the French employers’ association, when a humorous video clip of a teenage girl singing about her obsession with the quick-witted senator goes viral, Melenchon has been both a beneficiary of and in turn a catalyst for this opening up of the ideological terrain. His success undoubtedly forced not just Hollande but also Sarkozy to tack to the left on economic issues. Melenchon’s plan to tax everyone earning above €360,000 a year at a rate of 100 percent was matched with a more moderate policy proposal from Hollande that he would grab 75 percent of everything earned over €1 million. Cheap housing and penalties for layoffs also figured prominently in the Socialist’s platform, while Sarkozy promised a crackdown on wealthy tax exiles. “It is totally abnormal not to pay tax in France but to come back for healthcare,” the president told Europe 1 radio.

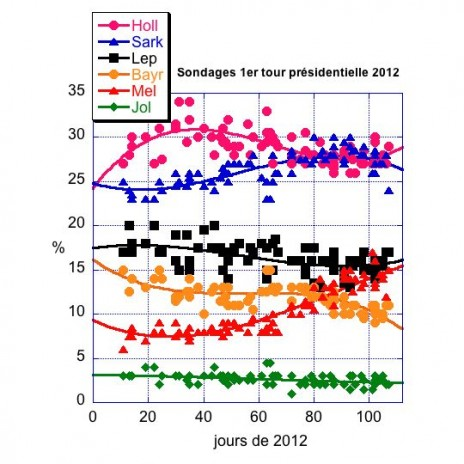

And yet, and yet. While Melenchon achieved a record score for the radical left, he did not achieve the 13-17 percent predicted in various polls. Unconfirmed online reports that a poll in early April by the DCRI, France’s internal security service, predicted that the Front de Gauche could advance to between 19 and 24 percent, with Hollande still in the lead on 23-29 percent and Sarkozy on 20-25 percent. However, the sources for this information is weak and such an interval lies as an extreme outlier from the trend seen when the variety of polls are plotted together, as seen in the graph below from French centre-left online magazine Rue89. In any case, it is enough to ask why Melenchon did not pierce the confirmed polling numbers. Worst of all, the FdG candidate did not push the Front National’s Le Pen into fourth place, as he had predicted.

The psephologists of the French left will be interrogating themselves over this question for months. This anglophone reporter hardly knows better than domestic experts. But let us remain with the broad outlines insofar as this helps us explore the significance of Melenchon’s result for the rest of Europe.

The Front National at the ballot box surpassed its poll-predicted trend, as the collection of polls towards the end of the campaign period had suggested the party would receive 15.5-16 percent, although it was beginning to tick upward again. Now, the far-right can sometimes do better than in polls, with some voters willing to cast a secret ballot for the fascists but not admit in public that they will do so. But the main attribute to be drawn from the aggregate of polls is the surprising stability of the FN numbers over the course of 2012 relative to the significant volatility of support for Sarkozy, Hollande, Melenchon and Bayrou.

Additionally, French far-right supporters seem to have been inoculated against the ‘Breivik effect’ that has, at least temporarily, hurt the far right in northern Europe badly. The sharp decline in Denmark’s hard-right Folkeparti is widely agreed to be a direct result of these ‘far-right lite’ parties being tainted with a connection to the Norwegian murderer’s ideas. The linguistic gulf between France and the rest of northern Europe will explain much of this. Others have suggested that the Jewish school shooting in Toulouse by Mohammed Merah was a gift to Le Pen. But the polling numbers belie this. It is precisely in this period that Le Pen’s numbers begin to dip. Sarkozy, who at this point overtakes Hollande in the polls for the first time in the campaign period, is instead the main beneficiary of the revival of the ‘securité’ discourse the shooting provokes, not Le Pen. Further, a slight dip in FN support can be seen coincident with the sharp rise in Melenchon’s fortunes at this same time.

Taken together, these numbers suggest two things - one worrying, the other hopeful. The general solidity of the numbers suggests a worrying consolidation of the far-right support under Marine Le Pen. Very disturbingly, she led amongst young people, with one poll putting Le Pen on 26 percent to Hollande’s 25, Sarkozy’s 17 and Melenchon’s 16. But Melenchon was also the only candidate to repeatedly take on Le Pen. In debates between these two, Melenchon very cleverly, often wittily unpicked key core elements of Le Pen’s narrative.

The far right has been advancing, although not in any uniform fashion. Nevertheless, this voting bloc seems to be consolidating. As far as this is concerned, the commentators who are noting that the hard-right response to crisis is winning adherents are broadly correct.

But at the same time, even in the face of clearly horrific criminal act seemingly tailor-made for the far-right to exploit - the shooting at the Jewish school in Toulouse, a confident pro-immigration, anti-Islamophobia discourse combined with progressive economic solutions can not only hold its ground but proves to be the best weapon there is against the far right. This further suggests that any successful movement against austerity must make defence of immigrants and the battle against Islamophobia - the new anti-semitism - a core part of the struggle.

Wilders is not the face of a Dutch backlash to austerity

The sudden collapse of the Dutch government, a coalition of right-wing liberals and Christian Democrats buttressed by the hard-right Freedom Party, has also been talked up in the press as part of this wave of anti-austerity fall-out across Europe as the Freedom Party’s leader, Geert Wilders, pulled his group’s support over disagreements about where to cut in line with EU requirements. A fresh election is now likely due to take place on 12 September.

However, the focus on Wilders as some anti-austerity maverick only aids the virulently anti-immigrant politician, who hopes to give precisely this impression to his electoral base.

"Either we opt for Henk and Ingrid [the names of an imagined ‘average Dutch couple’], or we opt for the unelected eurocrats from the superstate that's called Brussels," he said upon the withdrawal of his support for the government. As well as hiking healthcare fees, freezing wages, the effective abolition of social housing, cutting special-needs education funding and increasing VAT, the agreement on €16 billion in cuts crafted by the coalition would have increased the retirement age and cut benefits for retirees, in particular those with state pensions, both of which measures targetted a demographic that make up much of the base of the Freedom Party’s support.

Worse still for Wilders’ party, the group has seen its popular support steadily decline as it increasingly became tied to the policies of austerity while the hard-left Socialist Party (SP) saw its electoral fortunes soar to unprecedented levels, easily eclipsing the mainstream Labour Party.

Wilders emphasised the cuts to pensioners in particular when he pulled out: ““We don’t want to follow Brussels’ orders. We don’t want to make our retirees bleed for Brussels’ diktats.” But this suggests rather that the Freedom Party is less interested in opposing EU austerity than it is in preserving its electoral base.

The genuinely anti-austerity SP meanwhile, which has made EU austerity a centrepiece of its campaigning for months, seems to go unnoticed by much of the non-Dutch press, even though it is now the second party in the country. A survey by Maurice de Hond, a regularly cited pollster, put the SP on 30 MPs in the 150-seat lower house to the right-wing liberals of Prime Minister Mark Rutte’s 34, as compared with the Labour Party’s 24 and the Freedom Party’s drop to 19.

The conclusion has to be that the spectacular rise of the SP is indeed proof of a growing anti-austerity mood in the country, but as the Freedom Party’s support is being squeezed, it should not be categorised as an example of any growing resistance to the cuts.

Alongside these developments, it should be noted that one of the biggest hurdles for resistance to austerity in the Netherlands comes from the mainstream left. If the election were to take place today, according to the same de Hond poll, all the left parties taken together could cobble together a majority of up to 83 (depending on the composition of the coalition) against the right’s 66.

However, Green Left (the country’s Green Party), and D66 (left liberals) and the Christian Union (a small soft-left Protestant party) in the end supported the austerity plan in return for some concessions. An indecisive Labour Party ultimately voted against the bill, but the party has said it is not opposed to austerity as such, only to the speed with which it is being imposed and which areas will bear the brunt of the spending reduction. ““We don't object to the limits,” Ronald Plasterk, the party’s financial spokesman said.

This is not a situation that is isolated to the Netherlands. Across Europe, the centre-left - and in this we must include the continent’s Green parties - have consistently either supported austerity or presented only the most tepid opposition.

Another Irish ‘No’?

On 31 May, Ireland is once again set to vote in a referendum on an EU treaty. While the European Council this time has ensured that passage of the Fiscal Pact need not be unanimous, a No vote in Ireland is nonetheless viewed as giving ammunition to Hollande in any presumed fight with Merkel over the insertion of pro-growth clauses.

From the country whose populace has been the ‘best-behaved’ out of the bail-out brotherhood, compared to the string of general strikes and other popular demonstration other PIIGS nations have experienced, a No vote would strengthen a mood of opposition. Voters who vanquished the ‘natural party of government’, the centre-right republican Fianna Fail, in February last year, are now abandoning what remains of the Irish political establishment, the governing coalition parties of Fine Gael, the country’s second centre-right (if perhaps slightly further to the right than FF) and Labour, who are backing the Fiscal Treaty to the hilt. Sinn Fein, until recently a ‘fringe’ party in the Republic due to its connections to the IRA, has soared from 10 percent support last year to second place in polls.

An eastern ‘progressive insurrection’?

One of the most genuinely hopeful signs of resistance to austerity is of a growing willingness on the part of eastern European citizens to publicly demonstrate their opposition to austerity. In some cases, the scale of protest matches or exceeds that seen when Communism fell.

In the Czech Republic on 21 April, between 80,000 (police estimate) and 120,000 (organiser estimate) took to Wenceslas Square, birthplace of the Velvet Revolution, in a union-led protest to denounce cuts to pensions and healthcare as well as a string of corruption scandals. The unions have warned of an escalation of protests, including calling a general strike, if the government sticks to the austerity path.

The following Friday, the conservative Civic Democrat government of Petr Necas barely survived a confidence vote after several members of a junior coalition partner, Public Affairs, exited after the group’s chairman was convicted of bribery. Should the Necas administration fall in the coming months, the opposition Social Democrats, who have promised to overturn many of the austerity measures, are assured an easy victory. They currently maintain a 20 percent lead in the polls.

But such an election, delivering an additional social democratic voice to the overwhelmingly conservative-dominated European Council, would likely change little if similar government reversals in Romania and neighbouring Slovakia are any measure.

October last year, the right-wing government of Iveta Radicova fell after a libertarian coalition partner refused to back a strengthening of the eurozone's bail-out fund. Amidst a corruption scandal in which secret police wiretaps revealed meetings between governing MPs and financiers where public tenders were traded for cash, Robert Fico’s centre-left Smer party won a landslide.

The main focus of the election was the scandal rather than economics and Fico has since insisted that his government remains committed to austerity: "The government must, in the interest of the country and also because of a risk of international sanctions, respect a commitment to cut the deficit to below 3 percent in 2013,” he said upon his appointment by the president on 4 April.

There is a silver lining however, as the new government has said that it aims to increase the corporate tax by three points to 22 percent, introduce a new tax bracket for top earners within the country’s otherwise flat-tax system and to establish a special tax on financial transactions and raise property taxes on the rich.

Nevertheless, this guarded optimism must be placed alongside a recognition that under Fico’s previous administration after an election win in 2010, the leader went back his promises to reverse or cancel conservative economic policies and in 2012, he confronts a further weakened economy and potentially even greater market and EU pressure.

Similarly, on 27 April, Romania’s centre-left opposition alliance, the Social Liberal Union (USL), brought down the country’s government of Prime Minister Mihai Razvan Ungureanu in a no-confidence vote just two months after his conservative administration was elected.

Mass popular opposition has soared in the EU’s second-poorest member state against austerity measures that include a hike in sales tax to 24 percent and the slashing of public sector pay imposed by the EU and IMF under bail-out agreements with the international lenders. Here as well, the intensity of protests has not been seen since 1989.

Yet here too, 39-year-old USL leader Victor Ponta was quick to reassure markets in an interview with Reuters that he would not immediately cut the VAT to 19 percent from 24 percent as promised, but instead would cut it gradually to 20 percent by 2016 if he were to win in the November election. Additionally, the USL is to keep Romania’s 16 percent flat tax on income and profits, reversing an earlier commitment to the introduction of a progressive taxation system.

If it can be said that there has been an escalation of protest and resistance to austerity in the east, it remains hard to ascribe this to a movement that fits in with a generalised backlash against austerity across Europe as developments here cannot be separated from what are specific local conditions, in particular the role of corruption scandals. Poland, the largest economy in the east and Europe’s sole economy not to have experience recession during the crisis, has not seen developments akin to what has happened in the Czech Republic, Slovakia or Romania, other than a union-led anti-austerity protest of an estimated 40,000 last September.

Moreover, the leaders of Latvia, also subject to brutal EU-IMF bailout conditionality, repeatedly remind Brussels that it has been a good pupil of austerity with none of the protests seen in Europe’s south has instead seen some 10 percent of its population emigrate. Here, EU-demanded austerity has been a catalyst for resignation and flight, not resistance.

The response of a Czech reporter to the query of a Russian TV station whether after the local demonstrations together with the French vote: “Can one talk about a trend towards the left in the EU?”

“I would put it differently. [The] protest mood now involves people who are not disposed towards protesting, i.e., the centrists. They are infuriated at the open social inequality when five percent of the society has enormous income, while ordinary workers can hardly make the ends meet.

“We are not talking about left or right, but of elementary fairness. I am convinced that the EU is on the verge of radical transformation and there is a demand for a completely different type of European integration.”

What can be said is that popular opposition to austerity is growing but it remains amorphous and could as easily be channelled to the extreme right as to some genuinely progressive alternative to the EU economic orthodoxy. Readers will be familiar with stories of growing anti-Roma violence and anti-semitism across the east. But here as well, the lazy narrative of austerity being the midwife of extremism is too crude. Local specificities condition the nature of the growth of the right, which itself fluctuates dependent on a range of factors frequently unrelated to the politics of austerity. There is no recipe that says two cups of austerity and half a cup of structural adjustment will bake you a neo-Nazi cake.

German unions rising from their slumber?

Most significantly, there remains very little in the way of any popular movement in Germany against EU-led but Berlin-designed austerity. Worse still, German union leadership has been key to blocking more ambitious pan-European action. No ‘backlash’ worthy of the name can exist without at least something beginning to shift within the bloc’s largest economy.

And yet there is the whispering of something. IG Metall, the major industrial trade union, launched work stoppages the last week in April across the country and are set to intensify following the 1 May holiday. And IG Metall’s action takes place after a victory in March by Ver.di, the services union, which won a 6.3 percent pay increase over three years for 2 million public sector workers. The European Central Bank, which believes its current ultra-low interest rate policy is maladapted for the Germany economy but must also hold steady with a loose monetary policy for the sake of the rest of the eurozone, is following the dispute nervously.

A balance sheet for the ‘backlash’

This analysis has not attempted to take into account the state of play in every single EU member state, but instead has offered an appraisal of trends in some signal European nations in order to be able to aid a more clear-headed assessment of the continent-wide balance of forces than what might be suggested from some of the more excitable pieces seen in the press in recent days.

So what are the trends that can be teased out of all this? There does appear to be a spotty but growing electoral opposition to EU austerity dogma, with many parties losing power, but it is more accurate to say that it is incumbents - right and left - that are losing as the result of a generalised frustration than that some sort of self-aware anti-austerity programme is cohering. Equally, it is too simplistic to place the new left forces and the hard right should in the same basket, as in some places such as the Netherlands, the hard right is actually declining. New left forces are expanding in the West, but face uneven growth, while new shoots of resistance are sprouting up in the east, but local conditions often dominate. Questions of corruption and scandal here cannot be separated from the austerity question. And finally, though social democratic forces may be feeling bolder in their ability to rhetorically counter austerity, they rapidly retreat from this position once they have won.

Additionally, while media pundits are talking about some kind of pan-European wave of resistance, the truth is that each of the struggles remains for the most part isolated. There is as yet no pan-European movement against austerity. This isolation above all is what allows the core EU powers, as with the derision of Sweden’s finance minister, to ignore social upheaval even when it amounts, in Greece’s case, to over a dozen general strikes.

So what would be the pillars of a genuine ‘backlash against austerity’ or ‘progressive insurrection’? What would signify the establishment of some movement that would give pause to the policy-makers in Brussels, Berlin and Frankfurt, that would at the very least force them to acknowledge and respond to such a ‘contrepouvoir’?

Four pillars of resistance

The good news is that construction of each of these four pillars is already well under way. In the case of the first pillar, it has almost entirely been built.

1) Targetting the European Union and its anti-democratic structures

Until relatively recently, many people have been reluctant to make the European Union itself a target of opposition for very understandable reasons. Internationalism is the opposite of nationalism and all its dark consequences. Eurosceptics are in most cases outside Scandinavia a swivel-eyed, hard-right bunch of nativists. A Europe - indeed a world - without borders should remain a cherished goal of all who favour reason and brotherhood over ignorance and the fiction of national division.

However, it is not merely the case that the EU is basically all right but just happens to be dominated at the moment by Christian Democracy; its entire construction takes an actively anti-democratic form that aims at insulating policy-making from the interference of stupid citizens who do not know what is best for them. The European Commission, European Central Bank and European Court of Justice are all appointed; the European Council and Council of Ministers are legislative bodies that never undergo general elections and whose bills are crafted by diplomats; the European Parliament may be elected, but it is the weakest of the institutions, with little power even after the Lisbon Treaty.

However, in the last four years, the sometimes occluded anti-democratic nature of the EU edifice has been nakedly displayed in the imposition of austerity against the will of national electorates, in the effective removal of fiscal policy from the realm of democratic debate, and, most egregiously, in the overthrow of elected governments. The scale of anti-democratic atrocity goes well beyond the iniquitous but resoluble corporate regulatory capture that these structures have long encouraged. It is clear now to so many that Brussels does not govern in our name.

It remains the case however that despite all this, there remain many key progressive forces that would prefer to focus their criticism on the markets, financial institutions or conservative political forces. This is no longer tenable. The European system itself must be overturned - but this position must be wholly distinct from the nativism of the eurosceptic right.

The anti-austerity movement must at the same time be a pro-democracy movement. Our democratic demands must be just as prominent as our economic ones, which leads to the second pillar.

2) Proposals for a new Europe

The first pillar however is insufficient without a concrete series of proposals of what sort of Europe we do want to see. Those who are reluctant to criticise the EU out of fear of a return to a Europe of mutually antagonistic national economies, swords drawn, are right to demand of their comrades who are bolder in their criticisms of Brussels: “Well, what would you replace it with?”

Even if a brave, unwavering anti-austerity government came to power in one of the EU’s member states - even in an economy the size of France - capital flight and economic sabotage would very quickly undermine almost all efforts to chart a different path. And an economy the size of Greece would simply be crushed. Any successful response to this crisis will require mass public investment and continent-wide democratic planning. Constructing some form of transnational governance is unavoidable if a democratic, socially just Europe is to be built. Another European Union is not just possible, it is also necessary.

Yet the movements opposing austerity, such as they are, are for the most part simply reactive, opposing this or that policy. Few pro-active plans for the Europe we want to see have been placed on the table.

The dismantling of borders is a task for labour, not capital.

3) A pan-European network of grassroots activists that can issue calls for action that are widely supported

Here too, there is at least some advance over recent years, where other than a handful of EU policy dorks, very few amongst the forces of progressive politics even well into the years of crisis cared much about what the EU was doing. Palestine or Venezuela or climate change - important issues all - were simply sexier than boring old Europe.

Thankfully, this is beginning to change, not least with this conference and the work of a growing number of organisations and publications.

But what has been achieved across borders remains at the level of intellectuals and ‘activists with platinum air-miles cards’. Protests, direct action and strikes against austerity have been nationally focussed. This leaves the core structure that is responsible off the hook and unthreatened.

It is true that the European Trades Union Congress has brought some people together and called one day of action, but this has been a top-down, uninspiring process that was never intended to threaten anything. Without a strongly connected cross-border grassroots network of activists, trade unionists, faith groups and NGOs that has the capacity of calling and leading actions independent of official organisations, we are simply waiting for the day that the ETUC will pull its finger out and announce a European general strike. We have to be honest: that day will never come.

We have to build the movement ourselves - and it has to be built in Germany too.

4) Cross-border general strikes and direct action

It is a truism that electoral change without pressure from below has rarely if ever been sufficient to alter anything in a progressive direction, and with the European institutions, we don’t even have the opportunity to attempt electoral change. Other than to the European Parliament, there are no elections!

But one-day national general strikes - and European states in the last four years have seen many - seem to be insufficient to garner much response or even notice from elites. They pale in comparison to the juggernaut threat from markets. So we have to come up with some sort of resistance that matches this rather enormous scale. This means that it is no longer wishful thinking or impractical maximalism to suggest extended cross-border general strikes and direct action: these are the only tactics we have left.

It is true that a Europe-wide general strike is unrealistic, but at the same time it seems absurd that in the four years of the crisis, the continent has experienced dozens of general strikes and not once has there been any effort to co-ordinate action across borders. A powerful strike movement does not have to take place in all 27 EU member states to be effective: a two-day strike for example across just Greece, Italy, Spain, and Portugal, perhaps Ireland if it can be pulled off and whichever other states can be roped in, maybe in the east, would be tremendously powerful and would likely create a self-sustaining momentum of its own. It would scream to EU elites: “We know who our enemy is. The enemy is not just at home, but in Brussels and Frankfurt and Berlin as well, and we are united in our resistance to all of you.”

Other forms of resistance, such as civil disobedience and non-violent direct action, also co-ordinated across borders, can fill in the gaps between more official strike days. The disruptive targeting of key nodes and channels of distribution essential to the European economy can be forms of action that many types of citizens, from students to pensioners, can get involved with.

Everywhere European officials, commissioners, diplomats speak across the continent, they should be afraid of activists disrupting their events. The calendar is full of EU-related award nights, opening ceremonies and ribbon-cuttings across the continent that are legitimate quarry.

The pranks and denial of service attacks hackers mount against the record industry and Arab dictators need to be frequent occurrences that frustrate and slow the workings of EU websites and information channels.

It should be as common for actors and musicians and scientists and journalists to refuse honours, write open letters and speak out in public against EU austerity and for European democracy as it is for them to speak out about the West Bank or Tibet or orang-utans or breast cancer.

***

Only if all of these four pillars can be constructed - a development that is certainly attainable and need not take years - only then can the newspapers truly say that that a backlash, an insurrection, a revolt against austerity has begun.