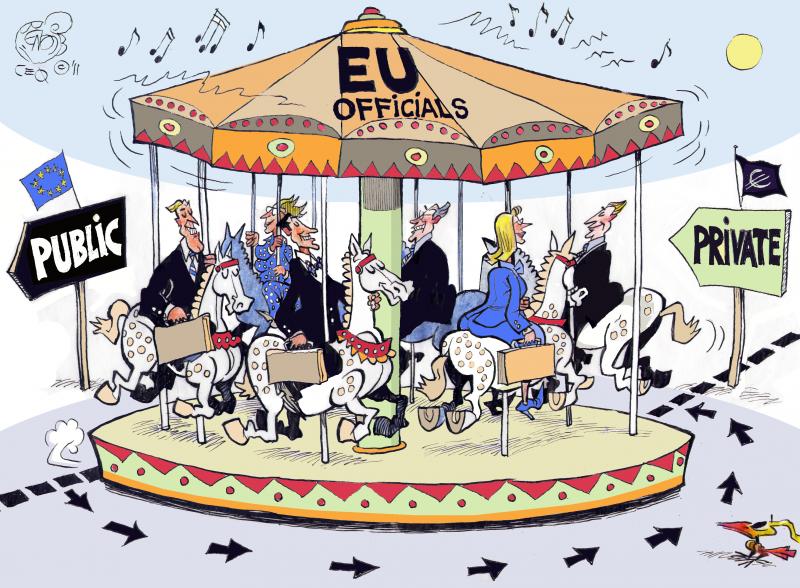

Commission's Refusal to Block Revolving Door triggers Ombudsman Complaint

Corporate Europe Observatory, alongside Greenpeace, Lobbycontrol and Spinwatch, have submitted a complaint about the Commission's repeated refusal to take the revolving door problem seriously. The 'revolving door' describes the movement of staff from public sector positions to lobby jobs in the private sector, or vice versa. The Commission's laissez-faire approach to the revolving door has failed to prevent former employees selling their knowledge and influence to industry, while industry lobbyists are recruited to work on the staff. Rules exist, but are not being properly implemented - and when breaches do occur, no proper sanctions are imposed. We have submitted a complaint to the European Ombudsman as we believe this situation undermines the credibility of decision making in the Commission, contributing to the corporate capture of the EU.

A large number of senior EU staff have moved through the "revolving door" to jobs as industry lobbyists, or vice versa, creating potential conflicts of interest.* Over the years that CEO and other watchdog groups have been documenting these cases, the Commission has seemed reluctant to take the breaches of its own rules seriously. Frequently failing to impose restrictions or cooling-off periods where there is clear risk of conflicts of interest, neglecting to impose sanctions when rules are breached, and systematically failing to properly scrutinise the moves.

The Staff Regulations that govern the EU institutions should ensure that staff are scrutinised for conflicts of interest, both when entering and leaving their position. For two years after leaving, staff must inform the Commission of new jobs. If such jobs relate to the work they did as an official, and could lead to a conflict with “the legitimate interests of the institution”, the Commission can forbid it, or approve it subject to appropriate conditions or restrictions. Yet the Commission repeatedly fails to ensure staff are aware of, or that they comply with, their obligations, it inadequately scrutinises new jobs, and fails to impose appropriate restrictions.

The complaint highlights 10 cases that illustrate the revolving door problem and the Commission's refusal to address it, including:

the former EU ambassador to the United States, John Bruton, who went on to became a senior advisor to Brussels-based lobby consultancy Cabinet DN. Bruton did not inform the Commission of his move and later said he did not know he was supposed to;

a former senior Energy Advisor in the Commission, Derek Taylor, who retired after 25 years, and immediately set up his own energy consultancy and took several other energy lobby jobs, but only applied for permission two years later. Despite this breach of rules, the Commission requested no further details nor imposed any sanctions or restrictions;

the Head of Cabinet to Enterprise and Industry Commissioner Verheugen, Petra Erler, set up an EU lobby consultancy with Verheugen immediately after leaving her post, but only applied for permission four months later, noting that she had not been made aware of this requirement. Authorisation was granted, with narrow restrictions, despite the documented disagreement of all staff representatives on an internal advisory committee.

We argue that such cases create the threat of conflicts of interest, allowing the former staff member is able to exploit their knowledge and contacts in the interests of lobbying for their new employer, providing the potential for excessive and undue influence. This contributes significantly to the corporate capture of European policy-making processes. Transparency International has described the "excessive and undue influence of lobbyists in the European corridors of power” as a form of "legal corruption".

The complaint's submission comes just days after the European Court of Auditors condemned the Commission's agencies for failing to manage conflicts of interest, including those created by the revolving door. The four Commission agencies, which make vital decisions affecting people's health and safety in the areas of aviation, chemicals, food and medicines, were all found to inadequately manage the risk of conflicts of interest.

The Court's investigation uncovered declarations of interest left unexamined in sealed envelopes by the chemicals agency. They found that EFSA, the food safety agency, saw no conflict of interest in their experts acting as private sector double agents - simultaneously providing private consultancy on the same concept they were scientifically reviewing. Nor was a conflict of interest identified in allowing the majority of a scientific body, designed to neutrally assess a concept, to be former advocates of that same concept.

It is becoming more and more evident that there is an institutional lack of recognition of the impacts that unmanaged conflicts of interest, and undue influence of corporate interests via the revolving door, have on public-interest decision making.

CEO, along with other civil society groups, have been campaigning for the Commission to take firmer action against revolving door cases, but Commissioner Maroš Šefčovič, in charge of transparency issues, has repeatedly dismissed these concerns, implying that there are no consistent failures, or that the revolving door problem has been solved.

This attitude, and the wider political culture, has precipitated our complaint to the Ombudsman. The 10 case studies, alongside our continually updated RevolvingDoorWatch, illustrate that the revolving door problem is alive and well.

Read the complaint here.

* The OECD defines a conflict of interest as occurring: “when an individual or a corporation (either private or governmental) is in a position to exploit his or their own professional or official capacity in some way for personal or corporate benefit.”