The MEP code of conduct: six months on

“The new code of conduct will be a strong shield against unethical behaviour.”

That was the verdict of the then European Parliament President Jerzy Buzek who had just shepherded the new MEP code of conduct through both his own European People's Party (EPP) group and the rest of Parliament. The development of the code followed the cash-for-influence scandal which saw three MEPs disgraced for tabling amendments in return for payment or lucrative second jobs and greater transparency via the new code was supposed to stop MEPs from ending up in the pockets of wealthy lobbyists. The code came into force on 1 January 2012, so six months on – how well has it fared so far?

Not readable, not searchable

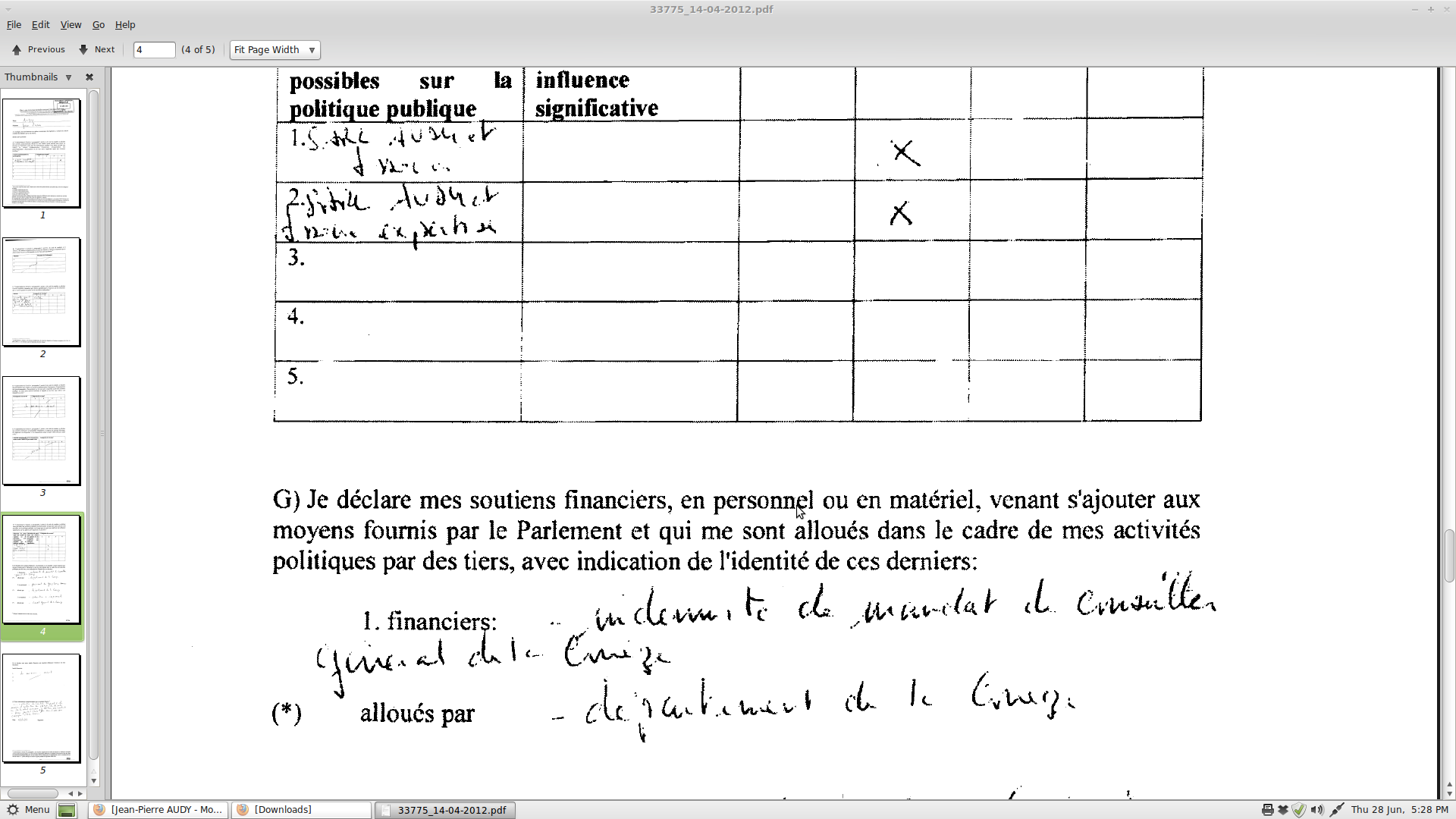

At the heart of the code is a new declaration of interest form which MEPs were required to complete by the end of March. The new form asked for much more information about additional income, including from second jobs; membership of boards; shareholdings with public policy implications and other information. Many MEPs are said to have struggled with filling it in by the deadline, and some sought advice from the new advisory committee (made up of five MEPs) about how to do so.

Since then, most if not all MEPs have completed the form, but a statistical overview is not readily available. In fact, scrutiny of these declarations of interest continues to be difficult. Many are handwritten (which can be hard to read, bordering on illegible); they can be completed in any EU language (which makes them hard to compare); and are not translated and uploaded onto a searchable database as the Alliance for Lobbying Transparency and Ethics Regulation had strongly recommended. Overall, the new forms may include more information than before, but they remain as challenging and time-consuming to scrutinise as ever. But such scrutiny remains incredibly important as there are concerns that some MEPs are not complying with the rules by completing the declarations as fully as they should.

Non-existent scrutiny

In May, Belgian media reported that ex-prime minister and current MEP Jean-Luc Dehaene had stock options granted by AB InBev (where until last year he served on the board) potentially amounting to around three million euros. Friends of the Earth Europe, CEO and other groups immediately wrote to the new President of the Parliament Martin Schulz (Socialist & Democrat) to raise the question of why those stock options were not declared in Mr Dehaene’s declaration of interest dated 27 February 2012. There is also the very serious question of whether, if Mr Dehaene does indeed hold these stock options, of whether they create a risk of a conflict of interest for MEPs who should act independently and in the public interest.

No response has yet been received to this letter but it is understood that Mr Schultz has now met with Mr Dehaene and that the case has been referred to the advisory committee for further investigation.

In this case, it was the media that first raised this issue. The parliamentary authorities have not devoted time to monitor or scrutinise MEPs' declarations or to clarify when things are not understandable (or legible). Instead, the parliamentary authority role seems to have been confined to purely one of administration and uploading the declarations when they receive them.

This is disappointing as codes of conduct do not tend to implement themselves and some proactive action and oversight is required, especially as a new system beds in.

Ex-MEP lobbyists with privileges

CEO has asked the Parliament a series of access to documents requests about how the rules will be implemented and enforced in one specific area ie. the clause in the new code which bans former MEPs from using their life-long Parliament access pass if they are undertaking lobbying activities. It is not clear how many former MEPs go through the revolving door into Brussels lobby jobs, but CEO is aware of a number of recent cases including Erika Mann, John Purvis, Christian Rovsing, Piia-Noora Kauppi and Karin Riis-Jørgensen.

CEO had assumed that the new code would mean that former MEPs engaging in lobbying would surrender their lifelong access badge (a perk awarded to all former MEPs when they leave office) at least for the duration of their subsequent lobby activities. Afterall, how else could you effectively enforce this provision in the code? But in fact, that is not how the Parliamentary authorities have interpreted the rules and as a result, it is understood that no former MEP has surrendered their pass. Instead the EP says it is “encouraging former Members engaging in representational activities to apply for [separate] accreditation via the Transparency Register … for the moment additional guidelines for the implementation of [this article] of this Code have not been produced.” It is not known whether any of the former MEPs listed above have accessed the Parliament for lobbying purposes using their life-long pass, but a check shows that none of the above are currently in the EP’s register of lobbyists, the Transparency Register.

Maybe it's too easy to criticise the European Parliamentary authorities for their hands-off approach to implementing the code of conduct for MEPs. Afterall, presumably they take their instructions from MEPs themselves - and perhaps the most shocking development since January has been the way in which senior MEPs have been willing to water-down and undermine the new code.

Gifts under the radar

In May, the Bureau (which is made up of senior MEPs including the parliament's vice presidents and the archaically named 'quaestors') voted to, in effect, weaken the rules regarding what MEPs need to declare when it comes to the receipt of hospitality and gifts. As a result, MEPs would no longer need to declare hospitality such as hotel accommodation received from a third party if it did not exceed a value of €300 per night. Paid travel would also not need to be declared unless it was in business class or first class. Undoubtedly, many EU citizens, who rarely get to travel business class or stay in swanky hotels, would likely be astounded by this move.

Cecilia Wikstrom MEP (Liberal) branded the move as "a complete disgrace" and the decision was subject to a particularly damning European Voice editorial. The Bureau hid behind its argument that they were simply acting in their role to interpret and implement the rules, but the effect was clear and what they decided was clearly a big step away from the original intention of the code of conduct. The EPP is the largest party in the Bureau, and to add insult to injury, Joseph Daul, the leader of the group in the Parliament later blocked any plenary debate taking place on the Bureau's decision, despite a request from the leaders of the Socialists, Liberals and Greens. MEPs, some of whom have been furious at this development, are now hoping that the Constitutional Affairs committee will take action to overturn the Bureau's decision although that will require plenary support.

Need for vigilance

CEO and other transparency groups welcomed the code of conduct when it came into force six months ago, but since then we have become more and more disheartened about how the parliamentary authorities and some MEPs themselves have responded to it. President Schulz inherited the code; he should take care that under his term of office, it does not morph from Buzek's “shield against unethical behaviour” into a fig leaf behind which unethical behaviour continues, business as usual.

This blog was updated on 3 July 2012.