The right to say no: EU–Canada trade agreement threatens fracking bans

As European Union (EU) member states consider the implications of environmentally risky shale gas development (fracking), negotiations are underway for a controversial EU–Canada Comprehensive Economic and Trade Agreement (CETA) that would grant investors the right to challenge governments’ decisions to ban and regulate fracking.

This briefing by Corporate Europe Observatory, the Council of Canadians and the Transnational Institute highlights the public debate around fracking, the interests of Canadian oil and gas companies in shale gas reserves in Europe, and the impacts an investment protection clause in the proposed CETA could have on governments’ ability to regulate or ban fracking. It examines the case study of the company Lone Pine Resources Inc. versus Canada, which, using a similar clause, is challenging a fracking moratorium and suing the Canadian government for compensation, and warns this could be the state of things to come in Europe. It recommends that the investor–state dispute settlement mechanism should not be included in CETA.

Fracking in the EU: regulators play catch-up

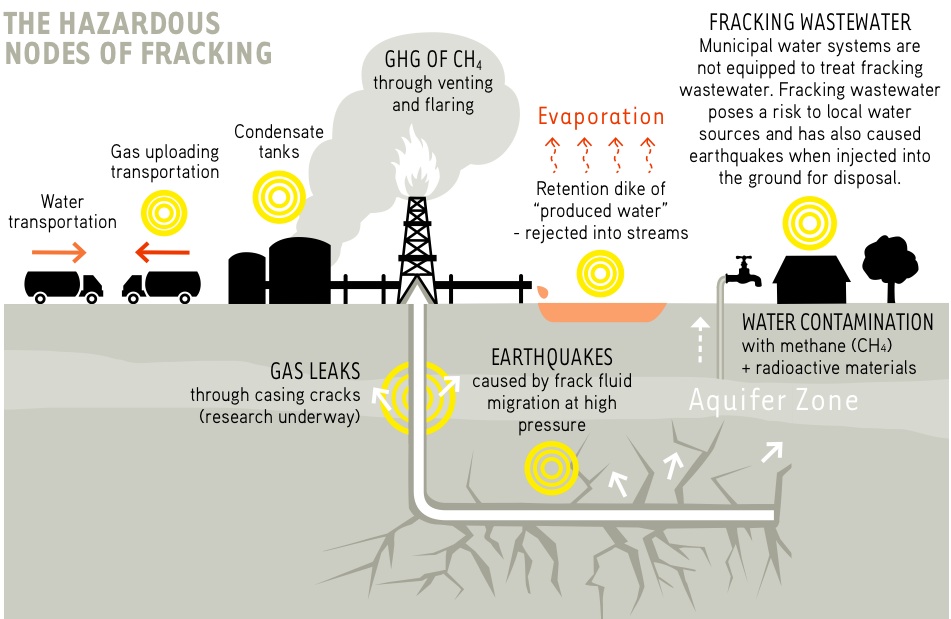

Fracking – short for hydraulic fracturing – is a newly popular technology to extract hard-to-access natural gas or oil trapped in shale and coal bedrock formations. The rock must be fractured and chemicals, sand and water propelled in to allow the gas or oil to migrate to the well. Each stage of the extraction process has considerable environmental risks, especially in terms of water contamination.1

Environmental and public health problems related to fracking have created popular distrust and resistance, to the extent that the majority of countries concerned with shale gas endowments in Europe (see map on page 3 in PDF version of this briefing) are taking positions against fracking. France and Bulgaria have already banned it, while Romania, Ireland, the Czech Republic, Denmark and North-Rhine Westphalia in Germany have proclaimed moratoria. As in the Netherlands, the UK and Switzerland, projects in the listed countries with moratoria have been suspended until further environmental risk assessments are done. In Norway and Sweden fracking has been declared economically unviable. Projects in Austria and Sweden have been cancelled for the same reason, though without legislative measures.

But powerful gas corporations are constantly pushing back against regulation.2 Despite citizens mobilisation, unconventional gas projects are underway in much of Spain and Poland. Even when a moratorium or a ban exists as in France, the industry exploits legal loopholes to push through its operations.

These struggles for the democratic right to decide environmental regulation are all the more important as to date there is no political consensus at the EU level regarding fracking. The issue is under debate, however: in September 2012 the European Parliament brought an amendment calling for a European moratorium on fracking that was supported by a third of Members of European Parliament (MEPs). The EU currently lacks clear regulation on fracking and it rests mainly on member states’ shoulders to legislate on the issue.

CETA threatens fracking bans

The EU and Canada are currently negotiating a free trade agreement that could threaten the ability of countries to implement fracking bans and regulations. There are many oil and gas companies with headquarters or offices in Canada who have already begun exploring shale gas reserves in Europe, particularly in Poland (see box 1). Though many of these firms are not strictly Canadian, a subsidiary based in Canada would allow them to challenge fracking bans and regulations through CETA. Moreover, there is ample evidence that firms will shift their nationalities in order to profit from such a treaty.

Box 1: North American Energy Giants Lead Fracking in EuropeTotal, a French corporation with a subsidiary in Canada, has invested in Denmark, Poland and France. In 2010, the Danish government issued two exploration permits to Total and despite a moratorium the company began exploratory drilling in that country. Total has one Polish concession. The company also invested in France prior to the moratorium and filed a legal appeal against its license being withdrawn. Chevron, a US-based company with subsidiaries in Canada, owns and operates four shale concessions in southeast Poland and since 2012 has been drilling exploratory wells. Before the Romanian moratorium, Chevron had the gigantic Barlad Shale concession. Chevron also had a 50% stake in an exploration and production company in Lithuania. In early 2013, Shell signed the biggest shale gas contract in Europe – a $10 billion deal in the Ukraine where it will drill 15 test wells. In 2011, ExxonMobil signed an agreement with Ukraine’s state energy company, Naftogaz. The company is pursuing shale gas potential in Germany, and in response to a moratorium in North-Rhine Westphalia, Exxon has developed a website to address public concern. In partnership with Lane Energy, Texas-based Conoco Philips is assessing the reserves of 1.1 million acres in northern Poland. Other North American companies interested in Europe’s shale gas reserves are Halliburton, Enegi, Talisman and Encana. |

The proposed CETA includes several chapters that would limit environmental, health or consumer protection regulations. These include chapters on so-called Technical Barriers to Trade and Regulatory Cooperation that will give the Canadian government more influence in how and when European governments act to protect the public good. Canada is already disputing the European seal product ban at the World Trade Organisation (WTO), claiming it is an illegal technical barrier to trade. Canada has also threatened to challenge the proposed European Fuel Quality Directive at the WTO if it labels fuel from tar sands as more polluting than conventional oil. One of the world’s largest deposits of the controversial tar sands is located in the Canadian province of Alberta.

CETA will also include a process through which a Canadian investor can settle disputes with the EU or a member state outside of the regular court system. This process, called investor–state dispute settlement, is increasingly controversial globally as mining and energy firms use it to challenge environmental, public health or other government measures that, in their terms, indirectly lower their profit expectations – or, in other words, run counter to their financial interests.

This investment protection provision will enable energy and extractive companies with an office in Canada to challenge fracking bans, moratoria and environmental standards for fracking sites across the EU – and potentially pave the way for millions of Euros in compensation to be paid to these companies by European taxpayers. Precedents already exist for these types of challenges under a similar provision in the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA), where a US energy firm, Lone Pine Resources Inc., is challenging a moratorium on fracking in the Canadian province of Quebec.

Investor rights trump democracy: the alarming case of Lone Pine vs Canada

North American governments are under enormous pressure from natural gas and energy firms to embrace fracking. While production is more advanced in the US, several energy firms are staking out claims to Canada’s large shale gas basins across the country. The Utica basin in the province of Quebec, sitting underneath the St. Lawrence River and Valley, is estimated to contain around 181 trillion cubic feet of natural gas.

But public resistance to fracking in Quebec, as well as growing documentation about water pollution, forced Quebec’s government of the day to be cautious. Public consultations on fracking resulted in the creation of a strategic environmental assessment committee. In 2011, based on the recommendations of a study by Bureau d’audiences publiques sur l’environnement, the Quebec government placed a moratorium on all new drilling permits until a strategic environmental evaluation was completed. Finally, a new provincial government was elected in 2012, promising to extend the moratorium to all exploration and development of shale gas in the entire province. At this point, Lone Pine Resources Inc. decided to use the investor rights chapter in the NAFTA to challenge the Quebec moratorium and demand US$250 million (€191 million) in compensation.

Lone Pine claims the Quebec moratorium is an “arbitrary, capricious, and illegal revocation of [its] valuable right to mine for oil and gas.” The firm says the government acted “with no cognizable public purpose,”3 even though there is broad public support for a precautionary moratorium while the environmental impacts of fracking are studied. Milos Barutciski, a lawyer with Bennett Jones LLP, who is representing Lone Pine in the arbitration, described the moratorium as a “capricious administrative action that was done for purely political reasons – exactly what the NAFTA rights are supposed to be protecting investors against.”4 It may seem unbelievable but this lawyer may be correct that Lone Pine’s right under NAFTA to make a profit is more important than the right of communities to say no to destructive and environmentally dangerous resource projects.

Essentially, this means companies in shale gas exploitation have their considerable investment risks reduced to near zero. If affected communities speak out against fracking, or the government changes its mind, it is the taxpayer who picks up the tab, not the firm – sometimes even if the government wins the investment dispute or settles beforehand. In investment arbitration, legal costs aren’t always awarded to the winning party.

The Lone Pine case is extremely significant for the EU and member states. It shows that governments are highly susceptible to investor–state disputes related to fracking and other controversial energy and mining projects, and that those firms eager to establish or expand shale gas exploration and extraction in Europe will be able to undermine precautionary measures in the public interest – as long as they have a subsidiary or an office in Canada. An investor–state dispute settlement in the proposed CETA would create needless risk to European communities weighing the pros and cons of fracking.

The right to pollute, the right to profit

EU member states already have experience with investor–state disputes undermining green energy and environmental protection policies. More than 1200 existing international investment treaties signed by EU member states allow companies to challenge public policy at private international tribunals. Germany has been sued by energy company Vattenfall for environmental restrictions on a coal-fired power plant, claiming more than €1.4 billion (US$1.8 billion) in compensation. The case was settled out of court after Germany agreed to water down the environmental standards, thus exacerbating the impact that Vattenfall’s power plant will have on the environment.5

Despite this negative experience, the EU is negotiating free trade and investment agreements that will allow foreign investors to bring similar legal claims against member states, including over measures to protect the environment and public health. If ratified, CETA will be the first EU-wide agreement to grant foreign investors such far-reaching rights enshrined in international law for Europe and Canada, which, even if eventually cancelled by either party, will remain in force for 20 years.6

Based on Canada’s negative experience under NAFTA’s investor–state dispute process – it is the 6th most sued country in the world and currently faces over US$5-billion (€3.8 billion) worth of NAFTA investment claims – the Canadian government is trying to limit when a company can invoke investment arbitration in CETA. However, EU negotiators are pushing back and seeking much more investor-friendly definitions for key terms in the treaty such as what would count as “direct” or “indirect expropriation,” or what would contravene an investor’s “fair and equitable” treatment (see box 2).

In the general context of controversy over fracking at both EU and member state levels, investor–state dispute settlement is a real threat to governments’ sovereignty. In cases where member countries already have a ban or a moratorium, such a process would allow these to be challenged. For countries moving towards permitting projects related to shale gas, or without a strong protective legal framework, the mere threat of an investor–state dispute could freeze government action. Evidence under NAFTA suggests that the threat of a dispute has a chilling effect when policy-makers realise they have got to pay to regulate.

The present EU regulatory framework concerning fracking is at an early and fragile stage, which could be severely undermined by investment rules within the CETA agreement. They are in potential conflict with democratic efforts to regulate and roll back fracking activities at both EU and member state levels.

Box 2: The Devil in the (Free Trade Treaty) Details“Indirect expropriation”: Allows investors to claim compensation as a result of a regulation, law, policy, measure or other government decision that has the effect of reducing or eliminating profit-making opportunities for the firm. Since almost any government measure can fit that definition when seen from a certain (investment-biased) point of view, legitimate public policies have faced investor–state lawsuits globally. Canada is proposing to include exceptions so investors cannot sue against regulations to protect public welfare, such as health, safety and the environment. Thus, Canada hopes to create more freedom to regulate without the fear of being sued. According to the leaked CETA investment text, the EU, on the other hand, would apply both “necessity” and “effectiveness” tests to such public welfare measures, in other words placing a very big burden of proof on governments to justify any measures such as fracking moratoriums or strict regulations on energy projects. “Fair and equitable treatment”: A vaguely defined minimum standard of treatment for foreign investors found in almost all bilateral and multilateral investment treaties. Because this clause is so vague and arbitrators tend to interpret it in an investor-friendly way, it is the clause most relied on by investors when suing states. It is cited in all of the current NAFTA claims against Canada.7 For example, a Canadian oil or gas company could argue that it was under the impression, given favourable signals from the EU or member state governments, that a fracking project was going to go ahead. This is exactly what happened in the Quebec case where the project was only halted by strong community resistance. Under CETA, a Canadian firm would be able to challenge this kind of moratorium or ban. Because of how broadly investment tribunals tend to interpret minimum standards of treatment, Canada is trying to narrow the definition of the so-called fair and equitable treatment standard in CETA. But again, the EU favours a more expansive, pro-investor definition in line with the type of investment treaties favoured by Germany and the Netherlands.8 |

No excessive corporate rights in CETA

The negative environmental impacts of fracking have been well documented and serious concern over the practice is widespread. Many governments are currently considering moratoria or exploration bans, especially in light of public health and environmental protection. These democratic proceedings and communities’ rights to self-determination ought to be respected, if not protected, and policy-makers should ensure that no treaties or laws can interfere with that process. In the case of fracking, moratoria are fully in line with the long-standing EU respect for the precautionary principle.

Clearly CETA, and in particular its planned investment chapters, will give corporations unreasonable and undemocratic rights to challenge fracking bans and to frustrate public interest regulation. CETA may also give EU-based energy companies with an interest in fracking the ability to skirt European laws by pretending to be Canadian to access the investor–state dispute settlement process.

In June 2011 a European Parliament resolution on the EU–Canada negotiations stated that, “given the highly developed legal systems of Canada and the EU, a state-to-state dispute settlement mechanism and the use of local judicial remedies are the most appropriate tools to address investment disputes.”9 In July that year, the Commission’s own Sustainability Impact Assessment of CETA came to the same conclusion, recommending a state-to-state dispute process only.10

The case of Lone Pine Resources Inc. suing Canada over a fracking ban shows that government policies on environmental issues can be undermined by granting investors the right to sue at international tribunals. Like their US competitors, Canadian energy firms and the Canadian government are eager to establish a strong presence in emerging European markets for shale gas. They, as well as US and European energy firms with substantial operations in Canada, could access CETA’s investor rules to file compensation claims similar to Lone Pine’s NAFTA case.

The mere possibility of a lawsuit based on investor–state arbitration can be enough to deter strong public health and environmental protection. Where fracking is concerned, it is unacceptable that the public should bear all the risks of extraction and the resulting environmental damage, as well then running the risk of having to pay compensation to energy firms for the right of communities to say no to fracking.

This situation brings new urgency to the need to exclude the investor–state dispute settlement provisions from CETA, and to rely on Canadian and European courts to settle disputes between foreign investors and host states.

- 1. For more general information about fracking see Transnational Institute (2013): Old Story, New Threat. Fracking and the global land grab, February.

- 2. See, for example: Corporate Europe Observatory (2012): Foot on the gas. Lobbyists push for unregulated shale gas, November.

- 3. See Lone Pine’s Notice of Intent to Submit a Claim to Arbitration Under Chapter Eleven of the North American Free Trade Agreement, 8 November 2012.

- 4. Quoted in: Gray, Jeff (2012): Quebec’s St. Lawrence fracking ban challenged under NAFTA, in: The Globe and Mail, 22 November.

- 5. In a similar case, Germany is currently being sued by Vattenfall because, after the Fukushima nuclear disaster in 2011, the German government decided to phase out nuclear energy. Vattenfall is seeking €3.7 billion (US$ 4.8 billion) for lost profits.

- 6. According to a leaked version of the consolidated investment chapter in the CETA from 7 February 2013.

- 7. Public Citizen (2012): Memorandum. “Fair and Equitable Treatment” and Investors’ Reasonable Expectations: Rulings in U.S. FTAs & BITs Demonstrate FET Definition Must be Narrowed, September 5.

- 8. Note that even Canada’s more cautious approach has proven futile in practice, where arbitration panels have ignored the common international law definition and used decisions of past tribunals instead, which will inevitably create pressure for increasingly pro-investor decisions. See, Porterfield, Matthew C. (2013): A Distinction Without a Difference? The Interpretation of Fair and Equitable Treatment Under Customary International Law by Investment Tribunals, in: Investment Treaty News, March 22.

- 9. European Parliament resolution of 8 June 2011 on EU-Canada trade relations.

- 10. A Trade SIA Relating to the Negotiation of a Comprehensive Economic and Trade Agreement (CETA) Between the EU and Canada, Trade 10/ B3/B06, June 2011, p. 19.