The European Stability Mechanism (ESM): no democracy at the bailout fund

The ESM, the euro area’s permanent bailout fund set up in 2012, is an international organization that operates behind closed doors, far from public scrutiny. The institution at the heart of EU loans to debt-ridden member states is doing its best to stave off any national influence over the conditions attached to its loans. In addition it is working closely with private consultancies, which appear to have conflicts of interest. However, the ESM is immune to democracy; we have no right to know what it is up to.

Leaked documents reveal that the ESM, the EU fund that provides loans to heavily indebted member states in crisis in exchange for austerity measures, refuses to allow its client countries any political influence over the execution of the loan conditionality; in order to speed up the privatisation process. In addition the ESM is very likely to be employing private consultancies with clear financial interests in these kinds of policies. Meanwhile the European public are kept in the dark about all of this. The EU institutions, as well as the ESM itself, do nothing but block attempts to shed light on the way the organisation goes about its work.

Permanent bailout fund

The European Stability Mechanism (ESM) began its work in October 2012, and is meant to be a permanent bailout fund for euro area member states with financial problems. It replaces the European Financial Stability Facility (EFSF), the fund that from 2010 arranged the distribution of loans to countries such as Greece, Portugal and Ireland. The EFSF will cease to exist after ongoing programmes finish and loans to member states have all been repaid.

The ESM can lend money up to a total maximum amount of 500 000 million euros. The money it uses to provide loans to member states comes from shares, bonds, and other products placed on the capital market, plus an obligatory contribution from the member states – each country in the euro area is automatically a member of the ESM. The loans provided to member states in need do not come for free; the ESM Treaty stipulates that the strict conditionality that comes with the loans has to be set out in a Memorandum of Understanding, drafted by the European Commission, European Central Bank (ECB) and if possible the International Monetary Fund (IMF) – together known as the Troika.

Because it is an international organisation (located in Luxemburg) and not formally classed a European Union institution or agency, the ESM does not have to adhere to rules or restrictions applicable to EU institutions and is not encumbered by any form of democratic accountability.

On transparency matters, this became especially clear: the ESM appears to be immune to the Commission’s Regulation 1049/2001 on public access to documents, or any similar rule that allows for greater transparency. Our attempts to receive information on potential contacts between the ESM and consultancy firms such as Oliver Wyman, BlackRock, Roland Berger, and Pimco which could represent conflict of interest issues have been answered with a curt, “No we can’t help you,” from the European Commission, and with complete silence from the ESM itself.

Troika’s consultancies

Our rejected request to documents related to research from journalists in several European countries who last December revealed contracts worth millions of euros between the consultancy firms such as the ones named above and the Troika, and countries suffering under its yoke. Their expertise has been hired in Greece, Cyprus, Spain, and Ireland, where these firms received large sums of money to provide ‘independent’ advice. This is despite these companies having zero accountability or transparency in their work and clear conflicts of interest, as they have links to private investment funds and other financial service providers, who may well be making a profit out of business not in the public interest.

Given the ESM’s close links with the IMF and its cooperation with the Commission and ECB (the three members of the Troika triumvirate), plus the fact that it is now the main provider of financial loans for European countries in economic difficulties, it is likely that these private consultancy firms are involved not just with the Troika and the indebted states but with the ESM’s business as well. But we are not allowed to get full clarity on this due to lack of any transparency rules for the organisation.

So why might allowing consultancy firms to handle EU bailouts be problematic? To illustrate: in January 2011, the Central Bank of Ireland hired – without public tender, due to Troika pressure – BlackRock Solutions to perform forecasts and a 'stress test' on worst-case scenarios for the Irish banks, in return for 30 million euros. Along with the fact that BlackRock's bank profit forecasts appeared to be far higher than the actual numbers, Irish MEPs feared a potential case of insider trading, or at the very least a serious conflict of interest. BlackRock Solutions had intimate knowledge about the condition of Irish banks, while its parent firm BlackRock had over 5 million euros of 'client business' and 162 billion euros of 'assets domiciled' in Ireland. Last year, it announced that it would buy three percent of the Bank of Ireland – one of the banks that was 'stress-tested' by BlackRock Solutions in 2011.

If BlackRock or similar consultancies are being used by the ESM, we need to be told. Yet because of the aforementioned complete lack of transparency on the side of ESM, we are not allowed to know the extent to which its agenda may be influenced by these consultancies.

At arm's length

A confidential but leaked ESM report delivered by the Troika to the Greek Government in June 2013 makes clear where the ESM’s loyalty lies (hint: this is not with the public interest). The report complains that the privatization process in Greece is not happening sufficiently fast: it identifies a “series of practical weaknesses in the current privatization process”, that lead to the observation that “the risks of implementation regarding the privatization programme and the related structural reforms continue to be significant” (p.31).

The current Greek institution responsible for carrying out the privatization schemes demanded by the Troika, the HRADF (Hellenic Republic Assets Development Fund), is, according to the ESM report, malfunctioning and should therefore be replaced by a newly established Holding Company. Most striking is the statement that Greece should not have any say in the privatization process of its own public services: “it is necessary that the Holding Company operates at arm’s length from the Hellenic Republic in all respects,” (p. 28).

As outlined in Annex I to the ESM report, “the majority of members of the Supervisory Board could be appointed by the Troika/ESM/EFSF” (p. 33). This Supervisory Board (“or the Troika/ESM/EFSF”, p. 34) then appoints the majority of the Board of Experts and the minority of the Board of Directors. The ESM proclaims that their proposed plan – setting up a foreign company that is part-ruled by the Troika to decide on the fire sale of Greece’s public services – will “combine in an obvious way the interests of the Hellenic Republic, its taxpayers and citizens and their creditors” (p. 31). However the ESM’s plan really serves only the latter.

Transparency’s trade-off

The ESM deals with millions of taxpayers’ euros, and the social consequences of the austerity programs attached to their loans have proved destructive (sky-high unemployment, reduced access to health care, increasing poverty and homelessness, and general demolition of the welfare state). Despite these far-reaching political consequences, little is known about the ESM's internal workings. It is hardly unreasonable given that the EU is meant to be a democratic system, then, to demand a fair degree of transparency over how the fund makes its decisions, who it consults, and why.

Yet up until now it seems that the ESM has followed its Managing Director Klaus Regling’s personal stance on transparency, expressed at a conference on the IMF over a decade ago: “there is a trade-off between transparency and efficiency[…] In an emergency, the fund has to be able to act quickly even if that reduced the understanding of outsiders.” The ESM seems to suffer from a permanent state of emergency, as the complete lack of transparency is ongoing.

Mr BailoutThe Managing Director of the ESM, Klaus Regling, has been in the front seat from the beginning when the first bailout loans were given to struggling EU countries, with harsh austerity measures dictated by the Troika attached. Initially this was through the EFSF, and since 2012 it has been via the ESM. Indeed even before this, he has been a key figure throughout the eurocrisis – and in a manner that raises some serious questions. Regling has an impressive CV that shows several jumps from the private sector to the public one and vice versa (in other words, he is a veteran of the revolving door). He started his professional career at the IMF in the 1970s, then worked for the German Finance Ministry, went back to the IMF, and in the beginning of the 1990s again to the German Finance Ministry. After that, he became Managing Director at the hedgefund Moore Capital Strategy group and moved straight afterwards to the job of Director-General at DG ECFIN (Economic and Financial Affairs) of the European Commission. Notably, in this function, he was responsible for checking Greece’s debt figures before it could enter the eurozone in 2001 – these debt figures later appeared to be much lower than the country’s actual debt burden at the time, thanks to a cover-up orchestrated by global investment bank Goldman Sachs through a legal but concealed ‘swap’ construction. One might be forgiven for thinking that this failure of oversight alone would be enough to disqualify him from further work in this area. Regling left the European Commission in September 2008, after which he started to teach at the Lee Kuan Yew School of Public Policy in Singapore for a year. He then established his own consultancy firm in Brussels, KR Economics, a firm that existed from 2009 until mid-2012. Regling was also a member of the Issing Commission, a high level Expert Group set up in 2008 by Angela Merkel to advise the German Government on how to handle the financial crisis. He was accompanied in this group by among others Otmar Issing (Goldman Sachs) and Jörg Asmussen (ECB director and former member of financial lobby group True Sale International ). The group has now finished its work, formally at least. From January until June 2010, still in the Issing Commission, Regling was Director of another hedge fund, Winton Futures Fund (part of Winton Capital Management, a British investment management firm). During this period, he was also appointed to write a report for the Irish Government on the origins of the crisis in the banking system of the country – while at the same time working as the Director of a hedge fund that made millions in profit from the banking collapse in Ireland. Winton is one of the world’s biggest managed-futures firms and its Futures Fund returned 21% in 2008 at the onset of the financial crisis, while the average hedge fund fell 19%. It generated large profits from capitalizing on price trends in futures markets (futures contracts are binding contracts to buy or sell a commodity, financial instrument or security at a specified price on a fixed date in the future) and the increased market instability in this year. After six months at Winton Futures Fund, Regling was assigned the job of CEO of the EFSF in July 2010 and two years later that of Managing Director of the ESM. In addition to revealing a past record that should raise some eyebrows, his CV symbolizes the deeply intertwined relationships between the financial sector and politics. |

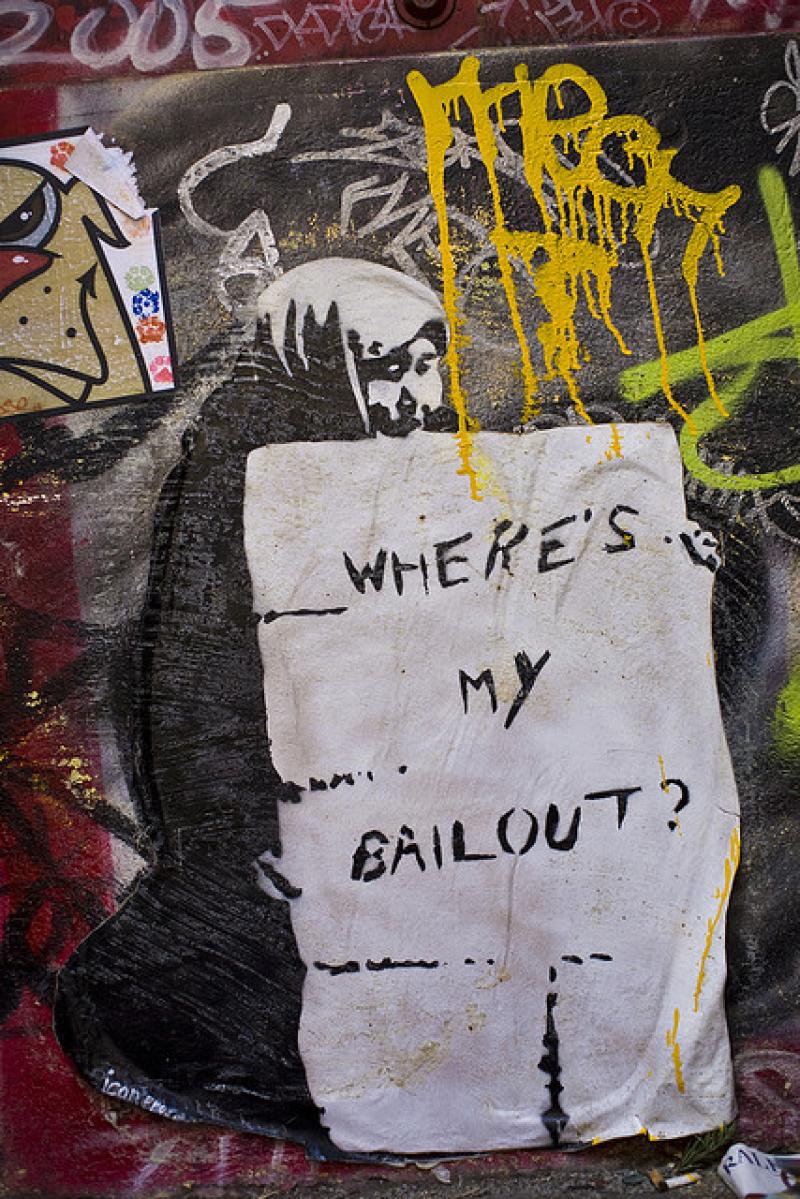

Image: Nicholas Noyes, Creative Commons 2.0 , via Flickr