Still not loving ISDS: 10 reasons to oppose investors’ super-rights in EU trade deals

At the end of March, the European Commission launched a public consultation over its plan to enshrine far-reaching rights for foreign investors in the EU-US trade deal currently being negotiated. In the face of fierce opposition to these investor super-rights, the Commission is trying to convince the public that these do not endanger democracy and public policy. See through the sweet-talk with Corporate Europe Observatory’s guide to investor-state dispute settlement (ISDS).

(For a detailed ‘reality check’ of the Commission's 'reform' agenda, see annex 1 and annex 2.)

In January, in response to growing public concern over the proposed EU-US trade deal (Transatlantic Trade and Investment Partnership, TTIP), the European Commission announced it was halting negotiations over the deal’s controversial investor rights to conduct a public consultation on the issue. This was an important success for the growing anti-TTIP movement, which is unanimously opposed to the corporate powers in the deal.

The consultation has now been published and the public will have until early July to participate. People in Europe should not miss this opportunity to tell the Commission (plus MEPs and member states) to axe the dangerous corporate rights in the deal once and for all. There are compelling reasons to do so.

Reason 1: ISDS is a tool for big business to make governments pay when they regulate

Around the world, companies use existing trade and investment agreements to claim compensation for perfectly legitimate government policies to protect health, the environment and other public interests – because they claim these policies have the indirect effect of undermining corporate profits.

For example, tobacco giant Philip Morris is demanding US$2 billion from Uruguay over health warnings on cigarette packets; Swedish polluter Vattenfall is seeking over US$3.7 billion from Germany following a democratic decision to phase out nuclear energy; and Canadian company Lone Pine is suing Canada via a US-subsidiary for CAN$250 million after the Canadian province of Quebec imposed a moratorium on shale gas extraction (fracking) over environmental concerns.

One crucial question for winning damages is whether these policies can be construed as “equivalent to expropriation”, even though the investor’s assets – a factory or land, for example – were not physically taken. The definition of expropriation – once exclusively used in relation to the confiscation of physical property – has now been expanded in corporations’ interests to mean action taken by governments that could potentially damage the earnings of corporations. According to this eye-opening article by journalist William Greider, enshrining this doctrine of ‘indirect expropriation’ into trade pacts was part of “a long term strategy, carefully thought out by business” to re-define “public regulation as a government ‘taking’ of private property that requires compensation”. The implications, according to Greider, are far-reaching – and that was exactly the intention:

"Because any new regulation is bound to have some economic impact on private assets, this doctrine is a formula to shrink the reach of modern government and cripple the regulatory state – undermining long-established protections for social welfare and economic justice, environmental values and individual rights. Right-wing advocates frankly state that objective – restoring the primacy of property against society’s broader claims."

Countries have indeed been asked to pay huge sums of money to companies under investor-state disputes. The highest known compensation to date, US$2.3 billion, was awarded to US oil company Occidental Petroleum against Ecuador, for the termination of an oil production site in the Amazon.

Reason 2: Corporate super-rights are an instrument to rein in democracy

There is evidence that proposed and adopted laws on public health and environmental protection have been abandoned or watered down because of the threat of corporate claims for multi-million dollar damages. Five years after the investor-state provisions of the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) came into force, a former Canadian government official told a journalist:

“I’ve seen the letters from the New York and DC law firms coming up to the Canadian government on virtually every new environmental regulation […]. Virtually all of the new initiatives were targeted and most of them never saw the light of day.”

It is commonly held that the threats of expensive lawsuits against governments have become more important and occur more frequently than actual claims. Rather than a shield to defend companies against unfair behaviour by states, investor-state dispute settlement serves as a powerful corporate weapon to delay, weaken and kill regulation. Specialised arbitration law firms constantly encourage their multinational clients to use that weapon to scare governments into submission.

“It’s a lobbying tool in the sense that you can go in and say, ‘Ok, if you do this, we will be suing you for compensation.’ It does change behaviour in certain cases.”

Peter Kirby of law firm Fasken Martineau about investor rights in trade agreements

Ongoing investor-state disputes can also have the effect of chilling legislation. A clear example is the announcement by New Zealand’s Health Minister to delay the enactment of tobacco plain packaging legislation until after Philip Morris’ claim against Australia’s tobacco rules has been resolved. This shows that the European Commission is only telling half-truths when it claims that its treaties will provide “absolute clarity that a state cannot be forced to repeal a measure” (p.3). Legislation to protect the environment or public health might very well be dumped in anticipatory obedience.

Scholars such as David Schneiderman from the University of Toronto have therefore aptly described the anti-democratic character of international investment treaties: “an emerging form of supraconstitution […] designed to insulate economic policy from majoritarian politics”.

Reason 3: The investor rights provide VIP treatment to companies

The investor rights in trade and investment agreements grant foreign investors greater property protection rights than are enshrined in national constitutions. For example, German law does not require compensation for ‘de facto’ (also known as ‘indirect’ or ‘regulatory’) expropriations – while they always have to be compensated under international investment law.

Also, German law does not consider expected profits as protected private property – but in investment disputes investors regularly receive compensation for alleged lost future profits. In a recent ruling against Libya, for example, a tribunal ordered the state to pay US$900 million for “lost profits” from “real and certain lost opportunities” of a tourism project – even though the investor had only invested US$5 million in the project and construction never even started.

A recent study on the costs and benefits of an EU-US investment treaty for the UK also argues that it could “grant US investors legal rights that they would not otherwise have in the UK” (p.40). Generally, legislation passed by Parliament cannot be challenged in UK courts; and while actions of the executive can be challenged, monetary damages are only rarely awarded. The exact opposite is the case under international investment law.

“The content of international investment law remains contested and uncertain, and it is possible that an ISDS tribunal formed under an EU-US investment chapter would grant a US investor significant damages for conduct that would not normally be actionable under UK domestic law.”

London School of Economics study on costs and benefits of an EU-USA investment treaty, p.27

To claim these greater rights, investors have access to a parallel legal system which is exclusively available to them: they can bypass local courts and sue states directly in private international tribunals. Domestic firms do not have this privilege, let alone common people and communities.

This VIP treatment gives investors the exclusive right to threaten and initiate claims at international tribunals that regularly impose large compensation sums on governments. In political debates over policies that affect a wide range of constituencies, this is a powerful privilege – and enhances investors’ bargaining power significantly.

To benefit from the ‘foreign’ investor privileges, big business and its corporate lawyers are engaged in what they euphemistically call “corporate structuring for investor protection”. Canadian company Lone Pine, for example, has routed its investments in Canada via a mailbox company in the US tax haven Delaware. That enables Lone Pine to sue its own government over a fracking moratorium in Quebec – on the basis of the greater private property rights in NAFTA, which are only available to ‘US’ and ‘Mexican’ companies.

Likewise, Spanish conglomerate Abengoa is using a Luxembourg-registered subsidiary to sue Spain over subsidy cuts in the solar energy sector – under the Energy Charter Treaty’s ‘foreign’ investor rights. The many Spanish cooperatives and ordinary people who also invested in renewables and lost out when the government cut the subsidies, however, have little recourse (See chapter 4 in our report Profiting from Crisis).

Reason 4: The investor-state arbitration system is fundamentally flawed

First, investor-state arbitration violates the principle of “equality before the law”. It privileges ‘foreign’ investors over local entrepreneurs, citizens, and communities who do not have access to this parallel legal universe that grants extra-judicial property protection rights and procedures.

Second, it is a very one-sided process. Only companies can sue governments. Abusive corporations cannot be sued, for example, when they violate human rights.

Third, the system is not judicially independent, but has a built-in, pro-investor bias. Investor-state disputes are usually decided by a tribunal of three for-profit arbitrators. Unlike judges, they do not have a flat salary, but are paid per case. At the most commonly used tribunal, the International Center for Settlement of Investment Disputes (ICSID), arbitrators make US$3,000 a day. In a non-reciprocal system where only the investors can bring claims, this creates a strong incentive to side with them – because investor-friendly rulings pave the way for more cases and more income in the future.

“Investment treaty arbitration as currently constituted is not a fair, independent, and balanced method for the resolution of investment disputes and therefore should not be relied on for this purpose.”

Osgoode Hall public statement of academics on international investment law

Finally, there is no judicial review by an independent court. Decisions are final and binding on countries – even if they are legally wrong and include huge fees that could bankrupt a government. Rulings can only be annulled on extremely restricted procedural grounds.

Reason 5: The Commission’s ‘reform’ agenda does not even touch upon these basic flaws of the system

The afore-mentioned serious flaws are inherent to the investor-state arbitration system. They are not addressed by the Commission’s ‘reform’ agenda as outlined in its public consultation. The corporate rights in EU trade deals as proposed by the Commission would:

- surrender the judgement over what policies are right or wrong to for-profit arbitrators with a vested interest in this privatised judicial system (even though they might have to sign a pretty meaningless code of conduct pretending otherwise in the future);

- grant investors greater rights than everyone else in a society (even though the Commission keeps denying that in their public PR);

- grant big business a powerful weapon to fight legislation by putting litigious heat on governments (which has arguably become the main function of the system);

- empower even more companies to claim financial compensation for perfectly legitimate policies to protect public health and the environment (though they would have to be more transparent about it and become more creative in constructing their legal arguments).

The Commission’s ‘reform’ agenda is about salvaging a legal regime reserved for the global elite that is increasingly contested around the world (see reason 9). (For a more detailed ‘reality check’ of this reform agenda, see annex 1 on the so called “substantive” investor rights and annex 2 on the “dispute settlement process”.)

The ‘reforms’ are remarkably in line with the big business lobby agenda to re-legitimise investor-state dispute resolution – by reforming it around the edges (transparency, faster proceedings, more consistent rulings, including through an appeal mechanism...), without touching its core (greater property protection rights and a private judicial system of for-profit arbitrators to claim them). (For examples of this agenda in action see the proposals put forward by the German industry federation BDI, and the European employers’ association BusinessEurope.)

Could Philip Morris sue the EU over anti-smoking legislation?European Commission officials claim that outrageous investor attacks against health and environmental policies would no longer be possible under the EU’s proposal for reformed investor rights. The ongoing Philip Morris claims are frequently cited as examples for claims that would no longer be possible under future EU treaties. The tobacco giant is challenging anti-smoking legislation in both Uruguay and Australia. Let’s look at the Philip Morris claim against Australia and compare it with the Commission’s plans for reform in order to avoid this type of scenario, as outlined in its consultation document:

We cannot know how a potential future Philip Morris-like claim against the EU or an EU member state would be decided. And we don’t know what kind of chilling effect it would have on anti-smoking legislation around the world. But it is pretty clear that the ‘reformed’ investor rights as proposed by the European Commission would not prevent such a case from being filed. |

Reason 6: The risks of being sued by big business are ever growing for governments

Over recent years, a number of factors have significantly increased the risks that states will be sued on the basis of the corporate rights in trade and investment agreements.

First, unlike a decade or two ago, the system is today well known in the business community. As law firm Freshfields put it in a recent briefing for its multinational clients:

“Businesses are now more attuned to the potential relevance of investment treaties, not only as last-ditch protection when things go wrong but also as an important up-front risk mitigation tool when entering into investments.”

Law firm Freshfields Bruckhaus Deringer

In an April 2013 memorandum, law firm Skadden praised the “increasing appeal and novel use of Bilateral Investment Treaties”, celebrating the “innovative uses” of these treaties by businesses, including as a means to challenge tobacco legislation and measures to combat financial crises.

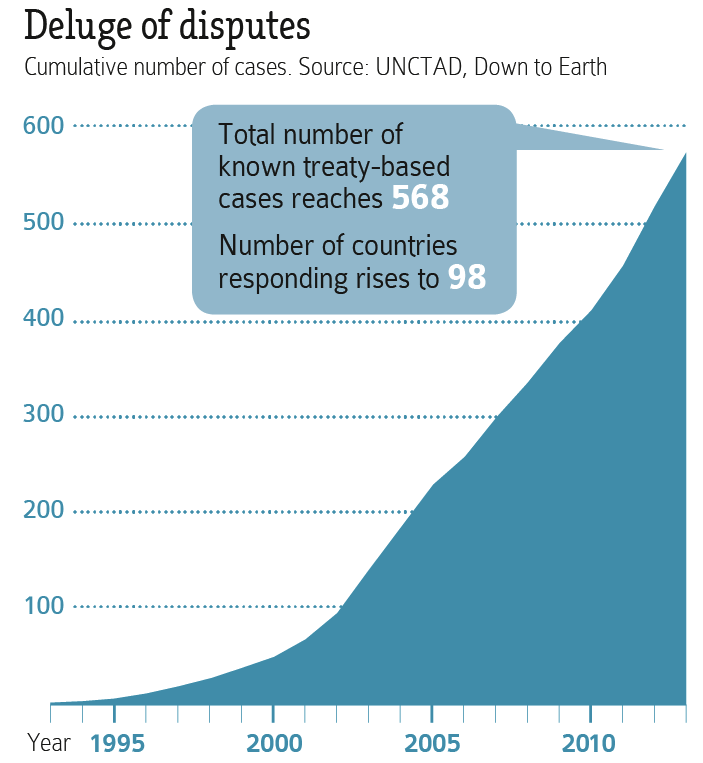

As a result, the number of investor claims against states has exploded: from a dozen in the mid-1990s to more than 568 known cases by the end of 2013 (because of the opacity of the system, the actual number is likely to be higher). According to UNCTAD, at least 57 new challenges were launched in 2013 alone, which is very close to the previous year’s record (58 new cases).

Second, as the number of investor-state disputes has grown, investment arbitration has become a money-making machine in its own right. Today, there are a number of law firms and arbitrators whose business model depends on companies suing states. Hence they are constantly encouraging their corporate clients to sue – for example, when a country adopts measures to fight an economic crisis. Sitting as arbitrators, investment lawyers have been found to adopt investor-friendly interpretations of the corporate rights in trade and investment deals, paving the way for more investor lawsuits against states in the future, increasing governments’ liability risk.

No wonder practitioners in the arbitration industry are already warming up for an era of more complex investment treaties (such as the ones the EU is negotiating). While some of them consider these newer treaties a more difficult base to bring claims, others envision a “brave new world” which will create even more work for arbitration lawyers (as argued by a partner of global law firm Arnold & Porter in a debate in London in February).

Third, to get access to the most business-friendly rights and arbitration routes, more and more companies have structured their investment through a dense net of subsidiaries. According to law firm Freshfields this “treaty planning […] now takes place alongside tax planning as investments are made” and existing investments are “audited for risk optimisation”. The result are claims such as the one by Canadian company Lone Pine suing its own government via a mailbox company in the US, or Spanish conglomerate Abengoa suing Spain via a Luxembourg-registered subsidiary.

Finally, another trend is reducing or even removing the financial risk of expensive investor-state claims for investors, making investment disputes even more attractive for them: third-party funders have entered the field, financing (parts of) investors’ legal costs in the hope of sharing in the spoils if a payout is awarded. By funding lawsuits that might otherwise be settled quickly or die altogether, third-party funding has the potential to multiply the number of disputes brought before arbitrators.

Question from the audience: Could you sue both [the EU and the US under TTIP] if you felt that some profits were foregone without justification?

John Atkin, Syngenta: Yes, all of the above.

Moderator: Depending on what works at the time?

John Atkin, Syngenta: Exactly. […] We’re a Swiss company. But we are listed on the US stock market. […] And we are very much active in Europe. […] We are a very good example of a global company.

Excerpt from a discussion on TTIP during the Forum for Agriculture, 1 April 2014, Brussels

Enshrining the excessive investor rights in agreements between capital exporting countries such as the EU and the US also multiplies litigation risks (one reason investment treaties between capital exporting states are very rare). The proposed transatlantic trade deal, for example, would cover more than half of all foreign direct investment in the whole of the EU, including in industries which have proven prone to investor-state claims in the past, such as extractives or water and energy utilities. According to research by Public Citizen, a total of 75,000 cross-registered companies with subsidiaries in both the EU and the US could launch investor-state attacks under the proposed deal. This danger is even more real given that EU and US businesses are well aware of how to work the system: according to UNCTAD, they account for 75% of all investor-state disputes known globally. Under the proposed corporate rights in the EU-US trade deal, companies could basically sue the living daylights out of governments on both sides of the Atlantic.

Reason 7: The investor privileges enable backdoor corporate attacks on court decisions

US oil giant Chevron is using an investor-state lawsuit to avoid paying US$9.5 billion to indigenous groups to clean up vast oil-drilling related contamination in the Amazonian rainforest, as ordered by Ecuadorian courts. So far, the three-man tribunal hearing the case has sided with Chevron, ordering Ecuador to block the enforcement of the ruling. But as such a move would violate the separation of powers enshrined in Ecuador’s constitution, the government did not follow the tribunal’s order. Now, Chevron is arguing that this decision is violating its right to ‘fair and equitable treatment’ in the US-Ecuador investment treaty and is demanding compensation. In this egregious misuse of investment arbitration to evade justice, Ecuadorians themselves might have to pay for the poisoning of their ecosystem – rather than the polluter that caused it.

“When I wake up at night and think about arbitration, it never ceases to amaze me that sovereign states have agreed to investment arbitration at all […] Three private individuals are entrusted with the power to review, without any restriction or appeal procedure, all actions of the government, all decisions of the courts, and all laws and regulations emanating from parliament.”

In another ongoing investor-state case, pharmaceutical company Eli Lilly is challenging decisions by the Canadian Federal Court to invalidate the company’s patents for two drugs (Strattera to treat ADHD and Zyprexa to treat schizophrenia). Canadian courts did so after finding that Eli Lilly had presented insufficient evidence to show that the drugs would deliver the promised long-term benefits. Strattera, for example, had only been tested in a short 3-week long study involving 21 patients. Eli Lilly is demanding US$500 million in compensation.

Reason 8: The investor rights do not bring the economic benefits claimed for them

In its public consultation notice, the Commission states that “investment protection agreements create a framework that encourages investment”. But the evidence on the link between investment treaties and investment flows is ambiguous. While some econometric studies find that investment treaties do attract investment, others find no effect at all. Qualitative research suggests that the treaties are not a decisive factor in whether investors go abroad. An internal EU Commission report from 2010 also admits that “there is no clear data” on the link.1

“Existing evidence suggests that the presence of an EU-US investment chapter is highly unlikely to encourage investment above what would otherwise take place.”

London School of Economics study on costs and benefits of an EU-USA investment treaty, p.44

Governments have also begun to realise that the promise of foreign direct investment is (FDI) not being fulfilled. Shortly before South Africa cancelled some of its bilateral investment treaties (BITs) with EU member states from the 1990s, a government official said: “We do not receive significant inflows of FDI from many partners with whom we have BITs, and at the same time, we continue to receive investment from jurisdictions with which we have no BITs. In short, BITs are not decisive in attracting investment.” The official also underlined the severe risks that the investor rights entail for government policy in times of major socio-economic and ecological challenges.

Reason 9: The global tide is turning against excessive corporate rights

Around the world, people and their governments are turning away from investor-state dispute settlement as they recognize how skewed it is in favour of big business.

South Africa, Bolivia, Ecuador, Venezuela, and Indonesia have started to cancel or phase out existing bilateral investment treaties. Ecuador, Venezuela, and Bolivia have withdrawn from the International Centre for the Settlement of Investment Disputes (ICSID), refusing to cooperate with it in the future. In Ecuador, a commission is investigating if the country’s remaining investment deals are beneficial and in line with its constitution. India is reportedly also reviewing its treaties.

Resistance to investor-state dispute settlement is also growing in Europe, with governments like Germany, Austria and France questioning the investor rights in the proposed transatlantic trade deal TTIP.

Legislators in the US are also becoming concerned. The National Conference of State Legislators, which represents all 50 US state parliamentary bodies, has announced that it “will not support any [trade agreement] that provides for investor-state dispute resolution” because it interferes with their “capacity and responsibility as state legislators to enact and enforce fair, nondiscriminatory rules that protect public health, safety and welfare, assure worker health and safety, and protect the environment.”

In international organisations, too, the tide is turning. The United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD), which pushed many developing countries into investment deals in the 1990s, is now focusing on reforming the system and assessing options for countries to terminate existing treaties. In addition to UNCTAD, the International Monetary Fund (IMF), too, has warned that investor rights can severely constrain countries’ ability to combat economic and financial crises.

Reason 10: There are alternatives

For governments, there are a number of policy alternatives to excessive corporate rights: not to grant them in the first place – for example, Brazil has never signed an investment treaty and yet has still attracted vast amounts of foreign investment.

Other countries do grant investor rights in their trade deals, but have become cautious in including investor-state dispute settlement provisions – neither the US-Australia free trade agreement nor the recently concluded Japan-Australia deal, for example, allow for investor-state arbitration. In case of a problem, an investor has to go to domestic courts.

The lesson is that the tide can be turned. Countries with investment agreements that have proven dangerous can follow the example of South Africa, Indonesia, Bolivia, Ecuador, and Venezuela and terminate them. This is also the case for the many bilateral investment agreements, which EU member states have signed between themselves (so called intra-EU BITs). They account for a growing number of lawsuits that EU member states are battling (according to recent UNCTAD statistics, 88 in total, approximately 15% of all known disputes globally). Treaty termination is also an option for the nine bilateral investment treaties between Eastern European EU member states and the US, which the Commission constantly uses as an excuse for its corporate investment agenda in the transatlantic trade talks (“these treaties are a problem, if we don’t replace them with a better treaty, we will have more cases”).

Countries can also follow the example of South Africa and update their national investment laws if they wish to clarify or change the protections for foreign investors.

Investors going abroad can insure their investment against political risks – via public investment guarantee schemes or private companies. They can also sign an investment contract with the host state when investing abroad.

Finally, the fact that corporations continue to commit grave human rights violations across the globe underlines the broader need to break with a system that has enshrined ever increasing rights and privileges for corporations without corresponding responsibilities. Initiatives such as the Campaign to Dismantle Corporate Power and Stop Impunity aim to reclaim public space currently occupied by corporate power and establish control mechanisms to halt abuse by transnational corporations.

How to stop the corporate power grab?

A close look at the Commission’s consultation on the investor rights in the EU-US trade deal (see annexes 1 and 2 for more detailed analysis) reveals that the process is, in reality, a mock consultation with a pretty much pre-determined outcome: the Commission’s own ‘reform’ agenda is a PR move intended to salvage an increasingly contested legal regime.

This is troubling because large chunks of the document labour the point about how rotten and dangerous the global investment regime is. This implies a far more fundamental approach to real change is required. Yet, the consultation does not ask if and why the corporate rights should be enshrined in the transatlantic trade deal at all – but rather, asks what the “modalities” should be. The Commission, it appears, is apparently not open to re-considering its agenda.

“A public consultation is not the same as a referendum. It’s not so that if you have 60 contributions say ‘away with ISDS’ that then we are going to do away with ISDS.”

Marc Vanheukelen, chief of Cabinet of European Trade Commissioner Karel de Gucht, during a TTIP debate at the Forum for Agriculture, 1 April 2014, Brussels

Nonetheless, the consultation period does create space for real debate and pressure. And people in Europe should use this space to tell the Commission, as well as MEPs (especially in the run-up to the EU elections in May) and member states, to axe the extreme corporate rights once and for all – not only in the proposed transatlantic trade deal, but also in other international agreements under negotiation with countries such as Canada, China, Myanmar, Malaysia, Singapore, Thailand and Japan, for example.

Here’s what you can do:

- participate in ongoing e-actions against corporate super-rights, for example, by SumOfUs and the European Attac network (also focusing in on other dangers in TTIP and its little brother, the CETA agreement between the EU and Canada);

- get informed and spread the word – with our campaign video “Suing the state” (also available with German, French and Spanish subtitles, just click on the symbol that looks a bit like a letter) and by checking out http://eu-secretdeals.info, where you will find many leaked negotiation texts and critical analyses;

- ask your candidate for the European elections to stand up against the extreme corporate rights in EU trade deals by supporting the Alternative Trade Mandate pledge campaign. Candidates can pledge to “protect public budgets and the state’s right to regulate in the public interest” by opposing the investor-state dispute settlement mechanism;

- and participate in the official consultation (we hope this text and annex 1 and annex 2 offer some helpful analysis on this front).

The good news about the consultation is that everyone can participate. Let’s use this opportunity to make it impossible for the Commission to ignore the fact that people in Europe do not want to wear a legal corporate straight-jacket.

- 1. European Commission (2010): Report Mission to Beijing, 9-12 March 2010, dated 12 March, Trade B1-MK/dc (2010) 2976. According to the report, the mission included a seminar on investment where “both parties agreed in principle that there is no clear data showing that BIT’s do improve investment flows, however they provide industry with the necessary legal certainty.” Obtained through access to documents requested under the information disclosure regulation. On file with CEO.