DG Internal Market’s expert groups: More needed to break financial industry’s stronghold

Corporate Europe Observatory – December 2011

Corporate Europe Observatory (CEO) was recently invited to meet with officials from the Commission’s Internal Market department (DG Markt) to discuss our criticism that many of the Commission’s advisory groups (the so-called expert groups) are dominated by the financial industry.

It turned out that DG Markt was not amused by CEO’s new Lobby Planet guide, our easy-to-read guide on EU lobbying. They felt that the text in the Lobby Planet guide does not reflect their efforts to implement Commissioner’s Barnier pledge to “re-balance” the expert groups. The officials admitted that there had previously been a problem of regulatory capture by the banking industry, but argued that the number of expert groups on financial markets is now much smaller and that composition of the groups has changed a lot.

They also said that they are now working on a charter of principles for expert groups and that the process of “rebalancing” would be completed by the end of the year. They introduced us to a new page on expert groups that has been added to the DG Markt website to showcase the changes made including with colourful graphs.

The information on the new DG Markt web page is radically different from what is in the Commission’s expert group register, but the officials argued that this is because that register is not fully up-to-date. According to the new web-page there are currently only 11 only expert groups left under DG Markt, whereas the register lists 38. The new web page has a section on financial services listing seven active expert groups advising on this particular area, compared to 19 groups dealing with financial issues in the register.

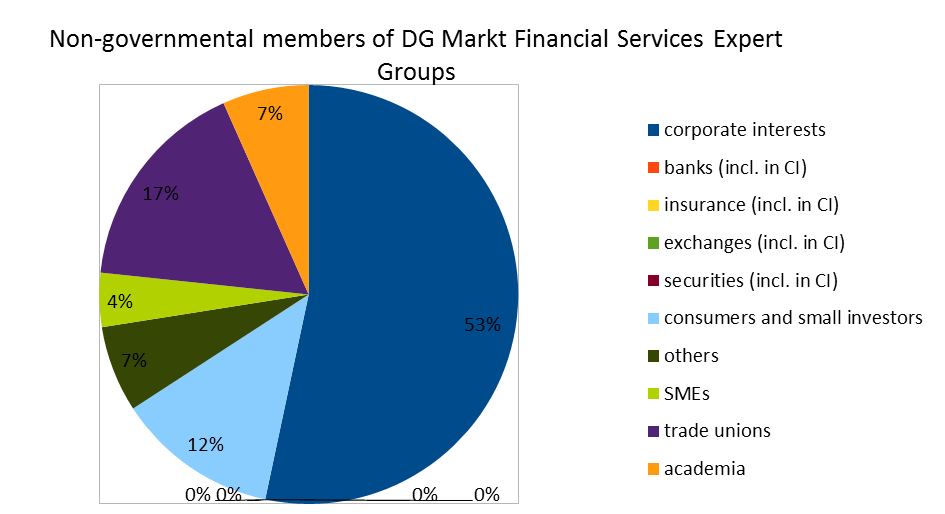

Assuming that DG Markt’s data are the most recent and accurate, the balance has clearly improved, but corporate interests still dominate, with 49 representatives from “private firms and industry associations” (40 of these from the “financial services industry” – banking, insurance, stock exchanges/clearing & settlement, securities/asset management) in DG Markt expert groups. We would add the 15 “consultancy firms” that are arbitrarily put in the same category as trade unions, SMEs and academia. Consultancies in Brussels are primarily hired to lobby for corporations. Take a look at the list of lobby meetings for British Conservative MEPs, and you’ll see many consultancies representing financial clients (G+ Europe, Interel European Affairs, Legal & General, Project Associates, Cicero Group and more). That makes a total of 64 out of 133 members of financial expert groups which means that 48% of the experts represent corporate interests. If we count the corporate percentage among non-governmental advisers only (so taking out the 13 representing national authorities), then we have 64/120 or 53%.

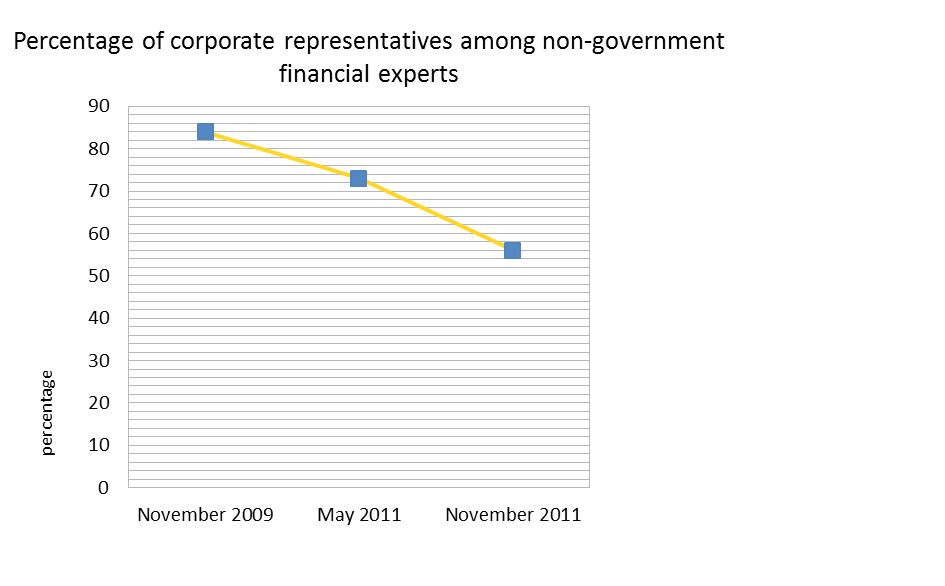

A closer look at the category “others” reveals additional industry representatives. For example in the Expert Group on Disclosure of Non-Financial information by EU Companies, groups like the IIRC and the ICGN1, which are mainly made up of corporate representatives, are listed under “others”. EABIS, which is listed as academia, is actually an ‘alliance of companies and business schools’ and most of its members are companies.2 So this percentage should be viewed with some caution. Again assuming that the data is correct, this would be a substantial improvement compared with the figures that emerged from the analysis that ALTER-EU made in May 2011 (73% or 202 out of 276 total non-government membership), not to mention the situation in 2009, before Commissioner Barnier took office (84%).

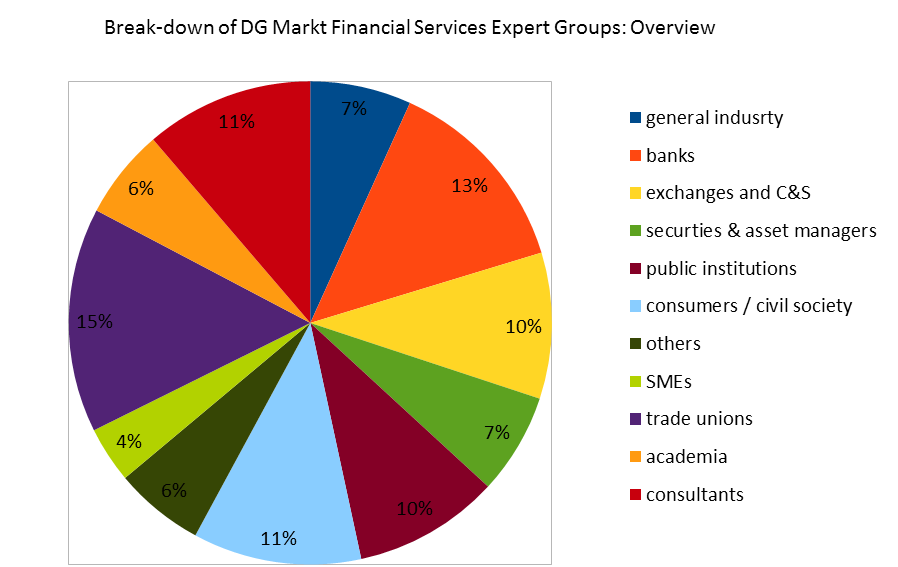

Here is DG Markt’s graph showing the composition of their expert groups:

Source: http://ec.europa.eu/dgs/internal_market/docs/expert_groups/composition_en.pdf

Note: We corrected the percentage of “general industry” since according to the Commission’s document they are 9/133 which makes 7 and not 6 percent (in fact 6,7%).

To get a clearer picture, we count all corporate interests together, regardless of whether they are banks, exchanges, asset managers or consultancies. We also take out member-state representatives (13 members or 10%) in order to see the balance between the different types of non-government interests. Member states are among the decision makers in the EU. What we are trying to find out is with which interest groups the Commission consults from wider society. As we said big business has 64 out of 120 non-government experts or 53%.

DG Markt has clearly made substantial changes to its expert groups over recent months. Numerous groups have been closed down and the number of experts consulted is far smaller than before. Most of the groups that have been closed down, however, were expert groups made up of national experts.

It should be acknowledged that DG Markt has made an attempt to create more balance in the composition of its expert groups, but there still is a need for more clarity regarding the exact number of the experts and their affiliation and an even better balance.

It should also be noted that the total balance is influenced a lot due to the 18 trade unionists that make up the Group of financial services employees’ representatives. CEO is in favour of trade unions being consulted more often in the drafting of financial policies. But putting all trade union experts together in a group that conducts only a vague general debate is not really the best way. Corporate-dominated groups like GEBI or EGMI are much more tightly related with specific legislative procedures. There should be fewer corporate and more employee representatives in the expert groups that really draft legislation. It will solve nothing if so called “alternative stakeholders” are put in separate expert groups with little real significance, like it happened in the past with the FIN-USE consumers group.

Further steps should be taken to break with the tradition of corporations’ privileged access to DG Markt. It remains unacceptable that corporate interests are still massively over-represented.

Problems around expert groups have caused uproar among MEPs. Last month, a large majority in the European Parliament took the unprecedented step of freezing 20% of the Commission’s budget for expert groups until the Commission acts to:

- “Provide safeguards against capture from special interests and corporate interests.”

- “Ban lobbyists and corporate executives from sitting in expert groups in a ‘personal capacity’.”

- “ensure agendas, minutes and participants’ submissions should be available on-line.”

Box: the good example of the consultative panels of the supervisory authorities and its bad implementation

The legislative framework set for the consultative panels of the three new financial supervision agencies in 2010 provided a threshold of up to 1/3 of experts coming from the industry concerned. This was a good decision. Unfortunately it has not been properly implemented by the European Banking Authority (EBA) and the European Insurance and Occupational Pensions Authority (EIOPA) which chose to re-baptise credit rating agencies, large accounting companies or even the corporate insurance department of Deutsche Banks as “users of financial services”. Using this trick they gave again the majority of seats in the panels to corporations. Small investors and consumers – represented by EuroInvestors and BEUC respectively – have filed a complaint to the European Ombudsman to demand the implementation of the legislation.

The idea of up to 1/3 industry involvement is a step in the right direction.

The principle of arms-length distance between lawmakers and civil servant and the industry they are supposed to regulate has to apply. But there is also no reason why shareholders from big companies – representing a tiny minority of the population – should make up half the membership of expert bodies, either through their companies’ executives or via lobby groups representing companies. The assumption that representatives of this tiny fraction of the population are the only ones who know how to run the economy means resigning from really implementing democracy.

Technicalities?

One of the reasons for the high percentage of corporate members in DG Markt’s expert groups is that some issues are defined as “technical” and thus limited to a select group of experts. The Insolvency Group is a good example of a group that should be changed since it is full of corporate lawyers close to the financial sector that sit there “in a personal capacity”. This situation is defended with the argument that the subject is “highly technical”.

The argument that certain “technical” knowledge can only be found in corporations shouldn’t be considered as valid. The inability of society to control what corporations – and financial industry in particular – are up to is one of the most important factors that have led to today’s crisis. The European Parliament has explicitly asked to scrap the “technical” exception from the Commission’s obligation to ensure a balanced composition (2012 Budget decision).

According to the Parliament, the Commission should clarify whether members of an expert group are there as stakeholders or as experts committed to acting in the public interest. The second category should be thoroughly checked for conflicts of interest and their declarations of “professional activities” should be in the public domain. DG Markt is still reflecting on whether to include this in its “charter of principles” (see above). CEO believes that DG Markt should also propose to the Secretariat - General to include this in the new general rules on expert groups that are demanded by the Parliament.

Too little too late

Expert groups dominated by the financial industry that were created after ALTER-EU flagged up this problem in 2009 have decisively influenced the latest round of financial reform. This was the case with the Derivatives Expert Groups (34/44 industry) that delayed legislation on credit default swaps and other speculative instruments that had a strong contribution in pushing the Eurozone into the debt crisis. The Group of Experts on Banking Issues (39/51 industry) was used in drafting the legislative proposals on banking. This partly explains why these proposals do not go far enough in defending the real economy and society from financial corporations’ greed. The current reduction of corporate experts happens in a context where the consideration of post-2008 financial reform is coming to a close with practically no major legislative initiative expected from the Commission. This makes it relatively easy for DG Markt to dissolve expert groups. The progress made in reducing the capture of the advice will prove useless, if before starting the next round of reforms, more unbalanced expert groups are set up.

There is also a risk that the Commission will replace expert groups with other forms of consultation that provide privileged access to the financial industry. This could be workshops with industry and hardly any with civil society on legislative issues. Consultation methods other than expert groups should also be balanced.

In any case a radical change of the composition is needed in groups like the the Tax Barriers Business Advisory Group (T-BAG),which is made up of 19 corporate representatives and only three others, the Expert Group on Market Infrastructures (EGMI) (31 out of 38 from industry) or the Single Euro Payments Area (SEPA) which is made up of six corporate representatives (Eurocommerce, BusinessEurope, European Payments Council, ESBG, EBF and “Payment institutions”), one consumer, one SME, one cooperative bank and five representatives of national authorities. This composition doesn’t correspond with the figures used for the Commission’s stats.

The messy situation with the membership information should be clarified and the register should become the most authoritative source of data regarding all the Commission’s expert groups. Otherwise, it is impossible for citizens, NGOs and journalists to scrutinise.

If progress in limiting corporate membership confirmed through data clarification, this progress will be a proof that civil society action can bring results and that citizens’ organisations and social movements should systematically challenge corporate capture in their respective policy fields.

DG Markt must accelerate the process of breaking corporate capture and further reduce the number of corporate advisers. It should also encourage the Secretariat-General of the Commission to establish common selection criteria for experts across the board and explicitly ban corporate capture.

Last but not least, DG Markt and the other DGs have still a long way to go to implement the Parliament’s demand for full transparency around the activities of expert groups.