Punishing the victims - a beginner's guide to the EU and the crisis

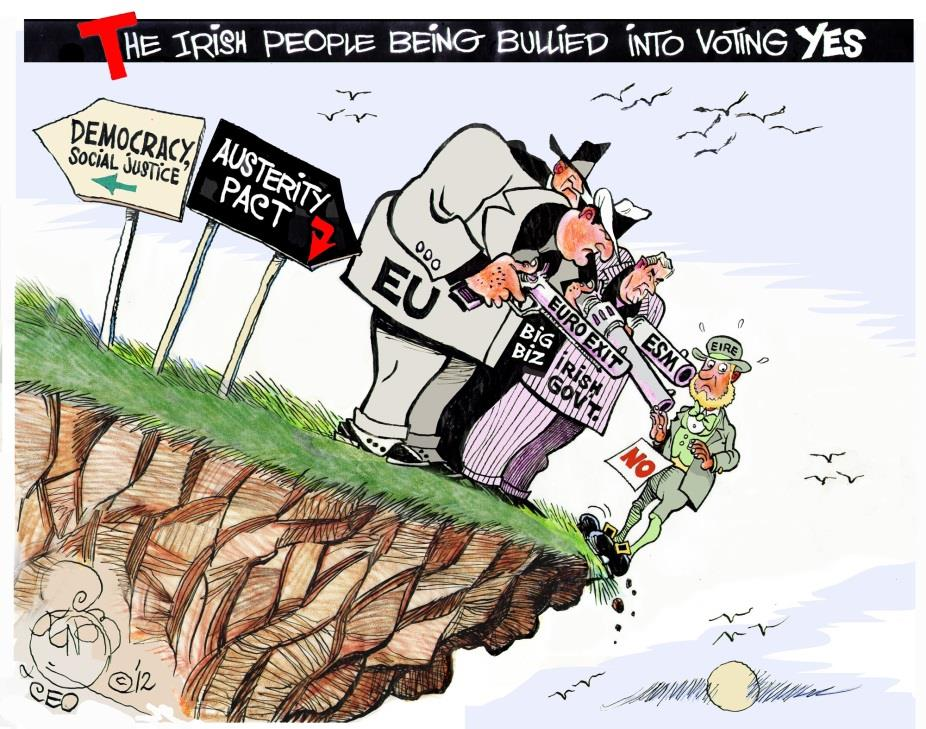

The eurocrisis has changed the face of the European Union. In its wake, new laws and untransparent governance mechanisms are being put in place that lock in austerity for citizens, and secure deregulation for business. Despite the fact that an unregulated financial market was one of the key causes of the crisis, it is Europe's populations who are being punished. The biggest threats to democracy, welfare and social rights in Europe today are the 'Troika' and the new system of neoliberal 'economic governance' being instated, with little public discussion, by the EU. This beginners' guide to the EU's austerity policies and the attack on social rights explains what rules have already been put in place – and some of what to expect next.

Download this text as a pdf

Find the key concepts discussed in this text, and their definitions, below

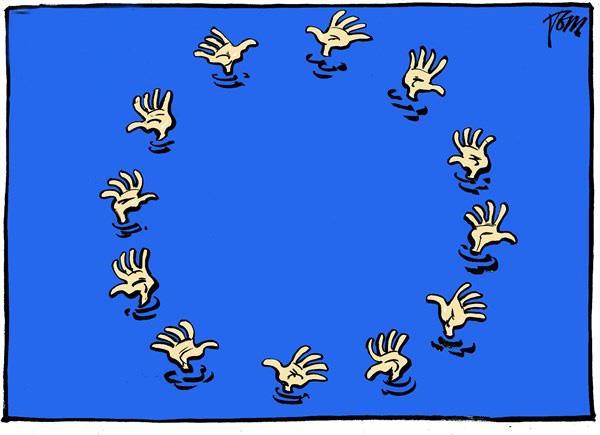

For over five years the economic and financial crisis in Europe has been hitting the continent hard. More and more people are losing their jobs, being evicted from their homes, relying on food banks or can no longer afford medical treatment. The crisis has affected people all over Europe, but it has been especially harsh in countries located at the Southern periphery of the European Union, in places such as Greece, Spain and Portugal.

What began as a financial crisis in 2008 due to the reckless speculation of banks, led straight to a second crisis in Europe, the eurocrisis. But in the end, it was not the banks or the speculators who were forced to pick up the bill. While claiming the crisis was the result of lavish public spending or laziness among workers in the countries most badly hit, the European economic and political elite prescribed a medicine that would hurt millions of people.

The taste of this medicine was clear from the beginning: harsh austerity measures were imposed, and policies were adopted to attack social rights, including pensions and labour laws across Europe – perfectly in line with neoliberal policy, that tends to serve the interests of corporations, finance, and elites.

These measures have been imposed in two different ways: firstly, through the so-called 'Troika', a triangle of three institutions – the European Commission, the European Central Bank and the International Monetary Fund – that has so far imposed harsh neoliberal austerity measures in four countries; and secondly, through a series of new EU measures and laws, introduced under the label of 'economic governance', installed particularly in the last three years.

These measures have been imposed in two different ways: firstly, through the so-called 'Troika', a triangle of three institutions – the European Commission, the European Central Bank and the International Monetary Fund – that has so far imposed harsh neoliberal austerity measures in four countries; and secondly, through a series of new EU measures and laws, introduced under the label of 'economic governance', installed particularly in the last three years.

The results were predictable. Experience from history shows austerity measures can lead to an even deeper crisis; and indeed there seems to be no end to the economic problems in several member states. Unemployment is sky high in many countries, particularly among the youth, social services are deteriorating, and poverty and inequality is on the increase.

Despite this, the European Commission and the Council have plans to further develop new ways of consolidating the same policies. This is because, fundamentally, big banks and corporations in Europe, who are doing very well out of these policies, have been allowed to set the agenda for the EU's response to the crisis.

Many of these developments are complicated, so we feel there is a need to provide a kind of 'beginners guide' to the EU in crisis. In the following, we will look at three questions: what caused the crisis in reaction to which the European institutions have implemented these neoliberal policies? What has been implemented so far? What new measures are on the agenda?

The financial crisis

What exactly are the roots of this crisis that made European institutions feel the need to intervene in the first place? According to the rhetoric of many governments as well as that of the European Commission, it was high government expenditure, high labour costs or unwillingness to pay taxes that caused the crisis in certain European countries.

In reality, the crisis in Europe was first sparked by a financial meltdown that started in the US in 2008 and quickly spread to Europe. Here, many economies were already in a fragile state, so they were prone to be hit hard when the global financial system started to break down.

The bankruptcy of the American bank Lehman Brothers has become emblematic of the start of the 2008 crisis. This was a bank that, like many others, had been deliberately giving out big loans and mortgages that were very unlikely to be paid back by its lenders, because of lowered standards for qualifying for them and sloppy risk assessment. A housing bubble that burst when banks realized that the majority of these loans would not be recovered sent shock waves through the entire global financial system. In September 2008, Lehman Brothers had to ask for suspension of payments and it became clear that it would not be able to get its finances in order again. The bank collapsed. Due to the high interconnectedness of banks worldwide, Lehman set a domino-effect in motion.

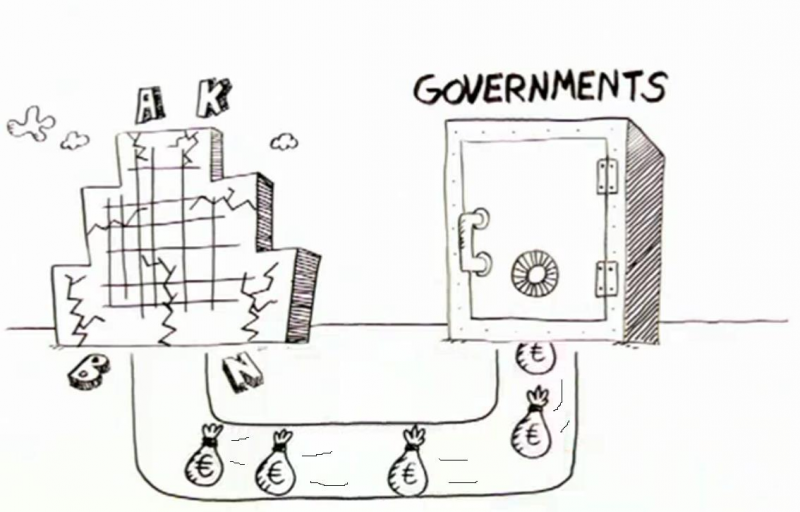

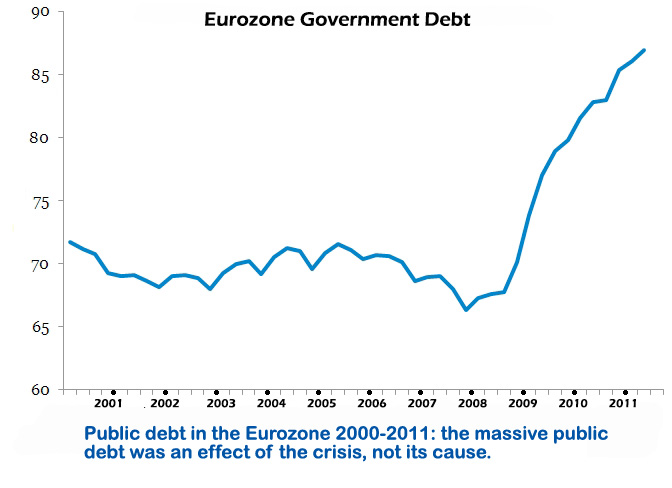

Confidence in the financial sector dropped dramatically and governments felt the need to prevent it from collapsing, by bailing out those banks they deemed would hurt the economy severely if they were simply allowed to go bankrupt – 'too big to fail'. These bailouts contributed to a huge increase in government debt; thus they are indirectly paid for by the citizens of a country.

The eurocrisis

The crisis led to severe problems all over Europe, but some countries were hit harder than others. The most serious problems arose in the eurozone, especially in Greece, Ireland, Portugal, Spain and Italy.

Why was this?

For almost a decade, so-called macroeconomic imbalances had been building up between the different countries in Europe. These kind of inequalities can for example be spotted by checking a country's balance of trade: some countries such as Germany had built up a trade surplus (simply put, this means that a country exports more than it imports) whereas other countries such as Greece, Portugal and Spain saw an increasing deficit (the opposite situation, when a country's import exceeds its export) appear on their trade balance.

The surplus on Germany's side was further augmented by policies of the German government that pressed wages down in the country. As a result, German enterprises are able to compete on the basis of very low production costs, damaging the 'competitiveness' of countries that already had a trade deficit and were unable to keep up.

If the common currency in the form of the euro had not existed, these countries could have used devaluation (lowering the value of a country's currency) in response, thus making its products cheaper, which can give rise to exports and reduce the trade deficit. However after the introduction of the euro, using this instrument was not an option any longer and countries with trade deficits found themselves in a situation that led to a build-up of debt.

The banks were to blame

This debt however, was in the first instance mainly of private companies and organisations, not on the governments' accounts. After bailing out the banks, however, governments now did have massive amounts of public debt. The balance at the moment shows that EU governments spent 1.6 trillion euros on ailing banks, according to the Commission. After that, countries did indeed have a public debt problem, but it was an effect of the crisis, not its cause.

Pre-crisis, countries such as Ireland and Spain had been praised by their EU partners for their economic policies, which kept the two countries strictly within the rules of fiscal policy in the EU. Also, Greece was considered to be on the 'right track'. But with the crisis, the enthusiasm in the higher echelons of the European Union was to vanish completely.

These countries were turned into scapegoats and severe austerity policies were applied on the false assumption that the problem was public debt and high wages. International creditors were to be repaid at any cost, while turning a blind eye to the suffering of the people. This approach to the crisis shows that the European elite have been bent on exploiting the crisis to further its own agenda, rather than looking at the real causes: the deregulation of financial markets and the effects of the euro that caused severe imbalances between countries, as explained above.

Furthermore, there is something more fundamental at play here: the crisis bears witness to some crucial traits of modern capitalism: with income inequality on the rise for decades, trillions of dollars and euros have been poured into financial speculation in ever more deregulated markets, making the system chronically fragile.

No real reforms for the financial sector

The logical move in response to the crisis would have been for European governments to review the euro, to address inequalities between countries, to act on financial institutions to halt or slow the endless flow of money into irresponsible speculation on the financial markets that creates such volatility and instability, and to ensure that no bank can be so big that it would need to be bailed out to prevent it from bringing down the whole financial system.

Unfortunately, that has not happened: neoliberal policy dictates that almost no restrictions or rules for the financial sector, that would prevent the same crisis from happening again, should be put in place. And powerful forces, such as the financial lobbyists, have succeeded in watering down ambitions to change financial markets. Reforms that have been adopted are piecemeal, half-hearted, and always, designed in a way that puts the interests of the financial sector paramount.

Instead, the European Commission and the European Council has focused on reactive measures – rules and procedures on how to deal with coming collapses of banks – as opposed to dealing with the root causes of the problem by taking preventive measures. For instance, the institutions are finishing work on a 'banking union' which will lead to a common approach for dealing with failing banks. They have however not been willing to pass laws that would prevent bank failure in the first place.

Instead of regulating the financial sector that caused the crisis in the first place, governments are shifting the heavy weight of the crisis on to citizens; in particular the poor, the young and the unemployed.

The Troika's deadly deals

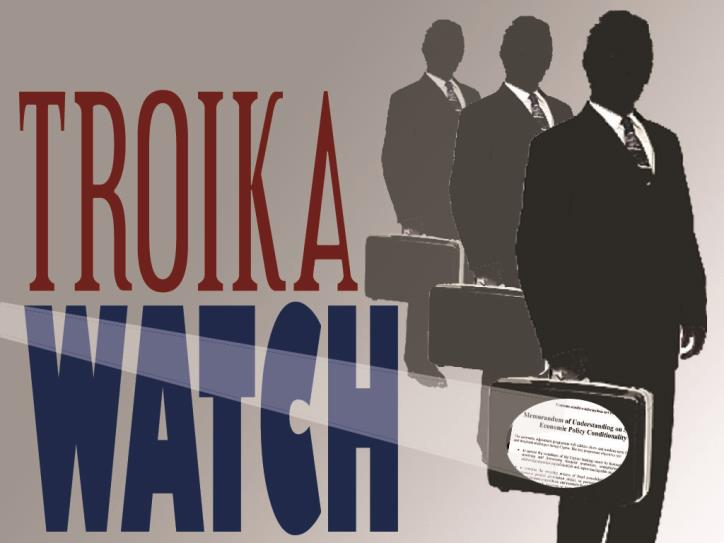

One of the key players in forcing economic reforms onto citizens instead of regulating the real originators of the crisis, is the Troika. The Troika (originally the Russian word for a carriage with three horses) consists of three institutions: the European Commission (EC), the European Central Bank (ECB) and the International Monetary Fund (IMF).

The Troika monitors countries in severe economic trouble that are receiving financial loans provided for by the EU and the IMF. These loans are aimed less at helping the countries' economies recover, and more at ensuring that their creditors will be paid back. In exchange for the loans, the Troika demands extremely harsh economic reforms and austerity schemes. Privatisations, lowering wages, firing public officials, cutting pensions and decreasing social expenditure are only some of the conditions of the deal.

The Troika monitors countries in severe economic trouble that are receiving financial loans provided for by the EU and the IMF. These loans are aimed less at helping the countries' economies recover, and more at ensuring that their creditors will be paid back. In exchange for the loans, the Troika demands extremely harsh economic reforms and austerity schemes. Privatisations, lowering wages, firing public officials, cutting pensions and decreasing social expenditure are only some of the conditions of the deal.

These measures and reforms, the conditions that countries have to fulfil to continue receiving money, are established in a sort of contract, called a Memorandum of Understanding (MoU). The Troika organises review missions in which it visits the countries it has a MoU with; if it concludes that a country has not done enough in exchange for the loans, it can decide to postpone payment of the next tranche of money. The Troika thus has a very strong influence on the national economic and financial policies of the countries that are under its rule.

The Troika acted for the first time in 2010, in Greece. It appeared that Greece's economic and financial situation was serious and as a last resort, the country asked for financial assistance from international institutions in May 2010. The EC, ECB and IMF undertook a joint mission to Athens and a few days later, a financial package was put on the table together with the first MoU. This started a downward spiral of one harsh measure after the other: the Troika had arrived.

After Greece, three other European countries entered into those deadly deals with the Troika: Ireland in December 2010 (in December 2013, it left the Troika program, at least formally), Portugal in May 2011 and Cyprus in April 2013. Similar schemes to the Troika ones have been imposed on Romania and Latvia, but without the participation of the ECB, as these countries were not part of the eurozone when loans were negotiated

When it started making these deadly deals with certain European countries, the Troika did not even have a legitimate role written into EU legislation. Only since March 2013, when the so-called Regulation on Strengthening of Economic and Budgetary Surveillance rule was put into place, has the Troika had an official basis. Unfortunately, this legal basis allows the Troika to continue its business as usual.

The Troika, with its neoliberal policies, should not be viewed as a stand-alone actor, but rather as an instrument that is part of a general push towards neoliberal measures and reforms in Europe. Because what we see is that the attack on social rights, democracy and the welfare system is gradually spreading throughout the whole of Europe, via a series of new laws and mechanisms that have been implemented over the past few years under the label of 'economic governance'.

We outline the most important ones from the European Union below:

Six Pack 1: make cuts or pay sanctions

The first part of the Six Pack, a set of six legislative texts that came into force at the end of 2011, was created to strengthen the Stability and Growth Pact (SGP) which exists to ensure fiscal discipline within all of the member states.

This pact states that government debt cannot be higher than 60 per cent of GDP, and the government deficit may not exceed 3 per cent of the GDP. If a country does not manage to keep its finances within these limits, it risks being put in the 'Excessive Deficit Procedure': follow a strict 'adjustment path', which includes neoliberal economic measures and reforms towards compliance with the SGP rules.

The Six Pack was designated to create faster compliance for countries to abide by the debt limits stated in the SGP. Time frames were shortened – meaning more rapid and bigger public spending cuts – and financial sanctions for not following this 'adjustment path' properly can now reach up to 0,5 per cent of GDP. That means: if you do not cut public spending fast enough or in the right areas, you are liable for a fine.

and bigger public spending cuts – and financial sanctions for not following this 'adjustment path' properly can now reach up to 0,5 per cent of GDP. That means: if you do not cut public spending fast enough or in the right areas, you are liable for a fine.

Next to that, the Six Pack made these financial sanctions more likely to be imposed, by introducing the principle of Reverse Qualified Majority Voting (RQMV). This means that sanctions can only be avoided by a qualified majority voting against them in the Council, rather than a qualified majority being necessary to impose them, as is usually the case. This procedure is sometimes called “semi-automatic”.

Six Pack 2: driving down wages

The second part of the Six Pack introduces new disciplines for macroeconomic imbalances. As discussed before, these imbalances mean that inequalities exist between the economies of European countries, for example with regard to their balance of trade, that shows surpluses for some countries (Germany, Finland) and deficits for others (Greece, Portugal, Spain).

As we explain above, production costs are a significant factor in determining the size of exports, as a cheaper product is more attractive to buy from another country: wage-deflating policies in Germany are thus an important cause of the country's trade surplus, since they made the production costs a lot lower than some other countries were able to keep up with.

To reduce the imbalances within the EU, rules in the Six Pack are meant to address these diverging costs of labour caused by differing national governments' policies. This leads to the flawed conclusion that bringing down wages will help countries leave the crisis behind them. In fact, it worsens the crisis and again, it is the victim that is being punished – in this case, in the form of lower wages for workers.

Because indeed, the procedures laid out in the Six Pack, in an attempt to 'harmonize' the wages and thus production costs in all EU countries, are not focusing on bringing the wages of the more 'competitive' countries up. Rather, the EU wants wages to be driven down, so as to make products cheaper in every country. Apparently, the European institutions consider the increasing number of German 'working poor' (only one consequence of the country's policy on labour costs), as an example that ought to be followed in every EU country.

To enforce the Six Pack's rules on macroeconomic imbalances, a set of indicators have been identified, including a maximum percentage rise of wages. If a country's wages rise too high over a period of time, it can be subjected to an 'excessive imbalance procedure', which can ultimately lead to sanctions. In other words, a country will be sanctioned for raising wages beyond a certain level pre-approved by the EU.

Fiscal Compact: perpetual pressure on public spending

The Fiscal Compact is part of the Treaty on Stability, Coordination and Governance that entered into force in January 2013. It takes European economic governance to another level, by strengthening the elements of its predecessors SGP and Six Pack.

A country has to pledge that it will not run a structural deficit of more than 0,5 per cent of GDP if its debt is above 60 per cent of GDP, and 1 per cent of GDP if the government debt is lower than 60 per cent. In short, this makes the demands of austerity even harsher than the rules of the SGP do.

Countries have to establish the rules and regulations from the Fiscal Compact in their national legislation, preferably into their constitution, within a year. The European Commission checks whether they have managed to do so, if not, a country can be brought to the European Court of Justice and receive a fine up to 0,1 per cent of GDP.

Countries have to establish the rules and regulations from the Fiscal Compact in their national legislation, preferably into their constitution, within a year. The European Commission checks whether they have managed to do so, if not, a country can be brought to the European Court of Justice and receive a fine up to 0,1 per cent of GDP.

This means that the Fiscal Compact is basically an agreement for eternity, as its rules and regulations will be fixed in national law, for the present government and all future governments of a country.

It also means that the democratic power of national governments is weakened, as these rules will always have to be applied, regardless of who the citizens vote for, whether a socialist or conservative government is in charge. On top of that, because it has to be enclosed in national legislation, the Fiscal Compact puts constant pressure on public expenditure, such as public investment, education, health care and the social security system.

The European Semester: controlling the budget

The so-called 'European Semester' was tried out for the first time in 2011. The term refers to the six-month period in which member states submit their draft budgets for approval. This starts every year in April, and not just their proposed budgets but any reforms or measures for economic growth for the upcoming year, are to be discussed and commented on by the European Commission.

Then in June, the Commission assesses these budgets and reforms for every member state, and makes country-specific recommendations that are adopted by the Council in July. In the months after that, member states are expected to take into account these recommendations in designing their final budget for the upcoming year; naturally these 'recommendations' follow the neoliberal model.

naturally these 'recommendations' follow the neoliberal model.

Initially, the European Semester was not meant to be a tool for the implementation of mandatory economic measures. However, the Commission intends to make it just that in the long run, as the European Semester was swiftly followed up last year by yet another pair of rules on economic coordination.

The Two Pack: enforcing the rules

Another set of measures called the Two Pack, executed for the first time in 2013, is again about tightening central control over finances. As the name suggests, the Two Pack consists of two regulations that are meant to reinforce the rules laid out in the Six Pack and the economic coordination process covered in the European Semester described above.

Firstly, the Commission from now on has the right to issue an opinion on the draft budgets presented by the member states, and can demand a revision of those budgets. If countries do not include the Commission's recommendations in their final budget, it can ask for further explanation on why these have not been taken into account. Further scrutiny follows on the distribution of expenditure in the budget, making the character of the budget controls even more strict.

Secondly, it provides for more explicit rules and procedures with regard to enhanced surveillance of eurozone 'countries in distress'. These include countries that fall within one or more of three categories: countries that face difficulties concerning financial stability, countries that receive financial assistance, or countries that are phasing out such assistance.

This enhanced surveillance involves an obligation to take on measures that target what the Commission believes to be the roots of instability, participate in review missions, implement an adjustment programme, seek technical assistance on it from the Commission if necessary, and accept financial consequences in case of non-compliance with this programme. For example, almost all member states have been recommended to implement fundamental reforms of their labour markets, including reduction of the significance of collective bargaining, measures to make it easier to fire people etcetra.

The Two Pack is a significant step towards centralised EU decision-making over member state budgets and economic policies. But it is not the final one.

Structural reforms: attacks on rights

For the EU institutions, boosting 'competitiveness' through attacks on hard-won social rights, is seen as the way to escape the crisis and stimulate economic growth. To reach this goal, more general 'structural reforms' are viewed as a necessary step: aimed at creating economic benefits in the long term – hence 'structural' – these reforms often mean privatisations, cuts in social spending and pensions, and attacks on labour laws in order to drive down wages.

Again, the threat of financial sanctions keeps the pressure on. If wages are not brought down to a level considered conducive to 'competitiveness' – that is, good for the profits of big businesses – if social expenditure is not kept low, and if pension reforms are not carried out or at least in the pipeline, several mechanisms are triggered to enact pressure or impose financial sanctions.

Again, the threat of financial sanctions keeps the pressure on. If wages are not brought down to a level considered conducive to 'competitiveness' – that is, good for the profits of big businesses – if social expenditure is not kept low, and if pension reforms are not carried out or at least in the pipeline, several mechanisms are triggered to enact pressure or impose financial sanctions.

Unlike before, countries outside the eurozone can now also be subjected to these procedures. This change allows the Commission to get involved in almost any kind of economic policy of a member state. But some areas are more significant than others. The Commission has been particularly keen on using this to push member states to reduce labour laws, reform pension systems, and other 'structural reforms'. The problem for the Commission – and the governments most eager to introduce these reforms – is that the EU does not have full competence in many of the relevant areas.

The next step: the contracts

The net result of all these new European laws and measures is that economic decision-making is steadily being taken out of the hands of nationally elected parliaments, not in order to be handled democratically at the European level, but to push neoliberal policies through via unaccountable bureaucratic mechanisms, and with the threat of sanctions as the ultimate weapon.

This has huge implications for democratic decision-making over how tax payers' money is to be spent, and who needs to be financially supported in times of crisis. Unfortunately, the near future of Europe does not seem to hold much improvement in this regard. New neoliberal reforms are already on their way.

Though the changes made since the beginning of the crisis seem massive, they could be just the beginning. In November 2012, the Commission released its long-term strategy for further reforms to make sure member states abide by neoliberal policies in the future. The strategy includes prospective reforms of the EU Treaty, to ensure that EU institutions have the greatly expanded powers to carry out the neoliberal reforms mentioned.

The next step is to have member states agree to conclude 'contracts' on economic policy with the Commission, contracts that would make it possible for the Commission and the Council to push through 'structural reforms', such as the attacks on wages mentioned above.

Meanwhile, the Troika left Ireland in December 2013, the first country to be released from its rule. The country will however remain under scrutiny through six-monthly surveillance. The questionable role that the Troika has played and the harsh neoliberal policy it is imposing on countries has also been noted by the European Parliament: a commission was set up that will investigate the democratic legitimacy of the Troika and the proportionality of the measures it has enforced; the final report should be presented before the European elections in May 2014.

The need for European action

It is clear that both the Troika and the ever more comprehensive system of neoliberal 'economic governance' are key elements of a European strategy – a strategy that is set to roll-back welfare, labour rights and even democracy. Some concessions can surely be won by major mobilisations at the national level, but to succeed in countering this attack, public awareness and pan-European coordination are needed.

The European elections are an opportunity to raise awareness and press new European elites towards changing direction. However, the issues raised by all the afore-mentioned policies of the European Union adopted during the crisis are fundamental, and they will not go away any time soon, but rather be at the heart of the struggle over Europe for years to come.

Further reading

On the Troika: www.troikawatch.net

On the European Semester: 'Business Europe and the Commission: in league against labour rights?'

On the business lobby and the crisis: 'BusinessEurope and economic governance'

On regulation of banks in the European Union: 'A union for big banks'

On the bank lobby: 'Stop listening to banks!'

On the Six-Pack: 'Austerity forever'

On the Fiscal Compact: 'Automatic austerity: ten things you should know about the Fiscal Compact'

On the two-pack: 'The dangers of the Two-Pack'

On the contracts: 'Mad men of the Roundtable' and 'Cracks in the armour'

Key concepts

Austerity | cuts in government expenditure, to a greater or lesser extent imposed in all EU member states |

| Bailout | the saving of banks on the brink of bankruptcy by national governments – because they are supposedly 'too big to fail'. This leads to an increase in public debt |

Economic | the sets of rules and regulations designed by the European institutions to govern economic and fiscal policy – generally, these lead to a shifting of power from the national to the European level. Mainly, economic governance is about imposing austerity and adopting “structural reforms” (see separate definition) |

| Eurocrisis | an economic and financial crisis that started in 2010 following the financial crisis two years earlier. Several countries in the eurozone saw their economies suffer a big blow, with public debt growing steeply, mainly as a result of bailouts of banks. It is most severely felt in countries located in the south of the European Union |

| European Semester | a six-month period in which the Commission and the Council check upon member states' budgets every year |

| European Union | an economic and political cooperation between 28 countries in Europe. Decisions are taken by supranational institutions and via intergovernmental discussions between member states. Over the past few years, the institutions have increased their power over economic and fiscal policies |

| Eurozone | the area within the European Union of the 18 countries that share a common currency, the euro. As a result of this, countries cannot use devaluation or revaluation of their currency to reduce a trade deficit or surplus any longer. This has led to imbalances between European countries, and low wages in Germany have made it particularly difficult for Southern European states to compete |

| Government Deficit | a government is running a deficit if it spends more than its revenues. Normally the figure for the deficit is measured in how much has been overspent in a year |

| Financial sector | banks and other financial institutions, such as hedge funds and pension funds, in their entirety; systemic problems in this sector form the roots of the crisis |

| Fiscal Compact | EU measures related to fiscal policy that entail constant pressure on member states' public expenditure, as those measures have to be fixed in national law. The Fiscal Compact came into force in early 2012. It envisages stricter rules on expenditure than the so-called Stability and Growth Pact (see below) |

| (Macroeconomic) Imbalances | these are the big imbalances between national economies. They can be about trade (with some winning, others losing), about 'competitiveness' and a lot of other things |

| Neoliberalism | the dominant economic and political theory of our time that favours free trade, privatization, and reduced public expenditure on social services and welfare |

| Six Pack | a set of six legislative texts, in existence since 2011, that regulate fiscal discipline and wage policy in the EU's member states |

| Stability and Growth Pact (or simply “the Stability Pact”) | the pact contains the key rules on fiscal policies. They are mandatory for eurozone countries and violation can lead to fines |

| Structural reforms | structural reforms are not clearly defined, but usually the term refers to long-lasting, fundamental reforms of social expenditure and labour markets, leading to lower wages and lower benefits or pensions. The often cited objective is to support the business sector by boosting its competitiveness |

| Troika | the triumvirate of the European Commission, European Central Bank and the International Monetary Fund that provides financial loans for which countries have to execute neoliberal policy |

| Two Pack | a set of two EU regulations that tighten the Commission's control on countries' budgets and ensure enhanced surveillance on countries in economic trouble |