The revolving doors spin again

Barroso II commissioners join the corporate sector

Summary

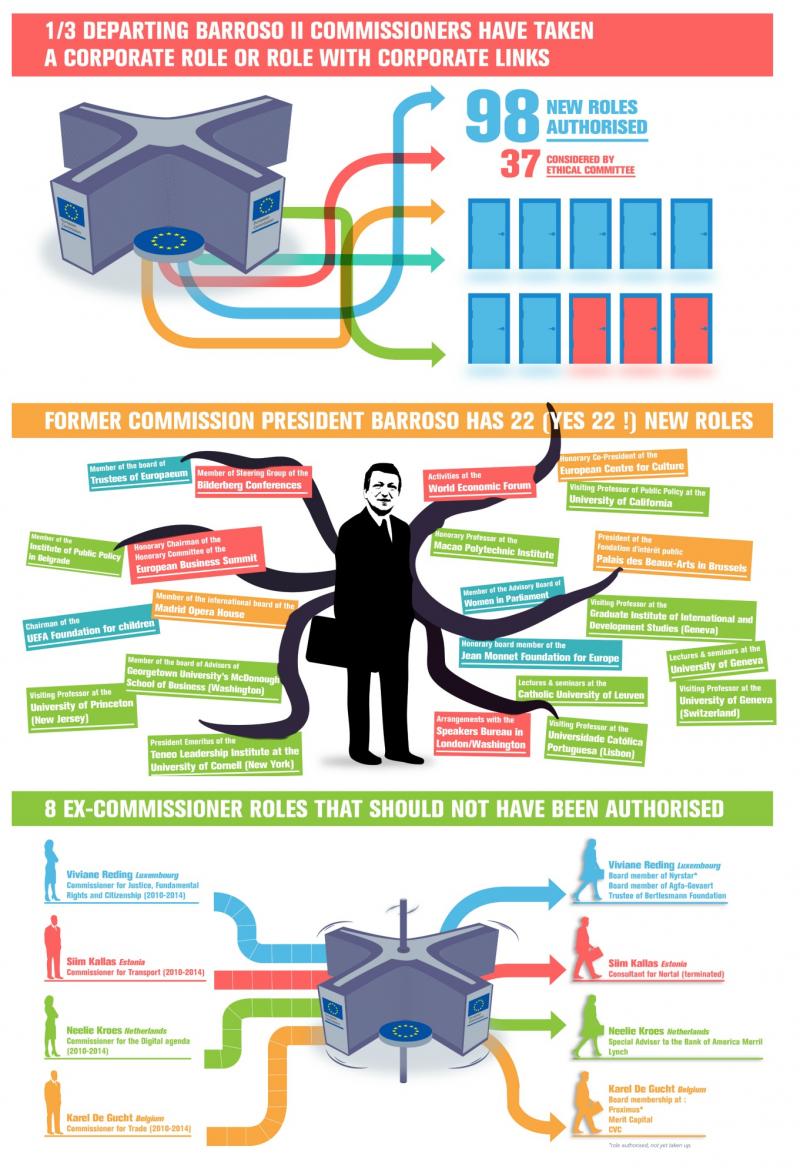

One in three (9 out of 26) outgoing commissioners who left office in 2014 have gone through the 'revolving door' into roles in corporations or other organisations with links to big business, leading to fears of an unhealthily close relationship between the EU's executive body and private interests, according to a new report (press release here). In our view, at least eight revolving door roles, held by four commissioners, should not have received authorisation at all, due to the risk of possible conflicts of interest. These are: authorisation of ex-commissioner (and now MEP) Viviane Reding to sit on the boards of the mining company Nyrstar 1, Agfa Gevaert, and the Bertelsmann Foundation (which has strong ties to the global media giant of the same name), and Siim Kallas to provide consultancy to IT company Nortal. Meanwhile, other members of the Barroso II Commission (which handled the fallout from the global financial crash of the late noughties) are now on the payroll of Bank of America Merrill Lynch (Neelie Kroes) and a major private equity firm CVC and wealth management firm Merit Capital (Karel De Gucht). Former Trade Commissioner De Gucht, who started the EU-US trade negotiations TTIP, has also received the blessing of the current Commission to join the telecoms company Belgacom (now known as Proximus) 2. Additionally, the former Commission President José Manuel Barroso himself has taken on new roles at the corporate lobby-fests of the European Business Summit and Bilderberg Conference.

This, however, is not a new problem. In 2011 Corporate Europe Observatory, LobbyControl, and others via the Alliance for Lobbying Transparency and Ethics Regulation (ALTER-EU) demanded better rules to tackle the revolving door after a series of scandals involving previous commissioners. We were told by the Barroso II Commission that its reformed rules reflect “best practice in Europe and in the world”. But the analysis in this report about the departing members of the second Barroso Commission, shows that the revolving door rules remain inadequate and poorly implemented.

Introduction

The tight-knit world of politicians, civil servants, industrialists, and lobbyists known as the 'Brussels bubble' lends itself to unhealthily close relationships between regulators and the regulated. Add in the phenomenon of the revolving door between the public and private sectors, and there is great potential for conflicts of interest. The revolving door reflects one aspect of the corporate capture of the EU decision-making process.

In the hierarchy of EU decision-makers the 28 European commissioners, one for each of the member states, would probably be regarded as the most important. Individually and collectively they are responsible for initiating and negotiating laws and regulations affecting 500 million citizens. It was therefore shocking to see the way in which five out of thirteen departing commissioners who served in the first Barroso Commission (2004-2010) spun through the revolving door into problematic new roles when they left office. Former commissioners, who collectively had just been handling the fall-out from the financial and economic crises, joined the boards of insurance giant Munich Re, bank BNP Paribas, and mortgage and life insurance company Credimo, to name just a few.

Most notoriously, Charlie McCreevy who had been the Commissioner for the Internal Market joined the derivatives trading unit of global investments company BNY Mellon, the board of Ryanair, and the board of Sentenial which offers payment technology to banks. Meanwhile, Günter Verheugen, the former Commissioner for Enterprise and Industry, founded consultancy firm the European Experience Company with his former Head of Cabinet, joined the international advisory board of lobby consultancy FleishmanHillard and became Senior Advisor and Vice Chairman of global banking and markets in Europe, Middle East and Africa at the Royal Bank of Scotland (RBS).

The furore that resulted was immense. Over 50,000 people signed a petition organised by the Alliance for Lobbying Transparency and Ethics Regulation (ALTER-EU) to demand action to block the revolving door. Eventually the rules, contained in the Code of Conduct for Commissioners, were reformed and mild improvements were introduced. See annex for a detailed explanation of the current rules.

Yet, despite this, as this report illustrates, the problem of the revolving door has continued as the Barroso II Commission left office.

Corporate Europe Observatory has demonstrated how attempts by corporations and corporate lobby groups to influence EU policies were more successful than ever under the Barroso II Commission, in part due to a close relationship with the Commission. CEO's Black Book showed how the Barroso II Commission came to act on behalf of corporations whether it was in the fields of climate, agriculture and food, or finance, economic and fiscal policies. The questions this report set out to answer are: to what extent has this corporate capture continued, via the revolving door, and how effective have the revised rules been in preventing it?

The new roles of the Barroso II Commission in 10 factoids

We have pulled together a spreadsheet of the new roles taken on by departing members of the Barroso II Commission. It has been collated from information in the College of Commissioners' published minutes, from access to document requests, and from other public sources. It is the only such spreadsheet publicly available. Here is a digested summary (all figures correct as of 23 October 2015):

|

For more details on all departing commissioners and their new roles, please consult our spreadsheet. The revolving door between the Barroso II Commission and the corporate sector

Despite the fact that the Code of Conduct for Commissioners was reformed in 2011 following the revolving door scandals involving the departures of members of the Barroso I Commission, major loopholes remain in both the rules and the way in which they are implemented (see annex at the end of this article). The failing rules allow the corporate capture of the Barroso II Commission to persist – even beyond office.

Viviane Reding (Luxembourg)

Viviane Reding (Luxembourg)

Old roles: Commissioner for Justice, Fundamental Rights and Citizenship (2010-2014); Information Society and Media (2004-2010); Education and Culture (1999-2004)

New roles: MEP; Board member of Nyrstar; Board member of Agfa-Gevaert; Trustee of Bertelsmann Foundation; and others

Viviane Reding left the Commission upon her election to the European Parliament in the May 2014 elections. Despite being an MEP she retains her ethical obligations as a former commissioner. However, she has secured authorisation for a number of new paid and unpaid roles. Most notably, she applied for and received authorisation to join the boards of two companies, the mining company Nyrstar 1 and Agfa-Gevaert (analog and digital IT), so long as she abstained from “lobbying and defending” the companies' interests to the Commission. The Ad hoc Ethical Committee was not consulted as these new roles were not considered to have links to Reding's former portfolio. This is surprising considering these are big corporations with multiple EU interests.

Reding was appointed to the board of Agfa Gevaert in May 2015; Reding has yet to join the board of Nyrstar. In our view, these roles should not have been authorised by the Commission. Reding was a commissioner for 15 years giving her huge internal knowledge, expertise, political know-how and contacts, skills that are likely to be of direct interest to these companies. She will also have taken collective decisions on many issues that are likely to be of direct interest to these companies. Yet as a board member she has a fiduciary duty to act in the interests of the company and this could conflict with her ongoing commitments to the Commission and the wider public interest.

Reding has received further authorisations of new paid roles, including as a member of the board of trustees (the Kuratorium) of the Bertelsmann Foundation, a politically-active think-tank. While separate organisations, the foundation controls the majority of shares in Bertelsmann, the global media corporation, (holding 77.6 per cent of the shares of the Bertelsmann Group) and three members of the supervisory board of the company Bertelsmann also sit on the Foundation's Kuratorium.

Reding's move to the Bertelsmann Foundation was assessed by the Ad hoc Ethical Committee and was authorised, so long as Reding avoided any conflicts of interest incompatible with the Code of Conduct for Commissioners “in particular when projects of the Bertelsmann Stiftung involved requesting and/or obtaining Community co-financing and that, within the 18 months after ceasing to hold office, she abstained from lobbying and defending the Foundation's interests to the Commission”.

Yet the Ad hoc Ethical Committee's assessment seems rather cursory, amounting only to one paragraph and apparently not reflecting on the deeper links between the company and the foundation, not to mention the wider interests of the corporation.

There is huge potential for the Bertelsmann media and services company to benefit from the political knowledge and contacts of Reding, particularly her know-how in the relevant media, privacy and education sectors. Furthermore, Reding was part of the Commission which initiated the EU-US trade negotiations (TTIP). Bertelsmann is a global media company likely to benefit from TTIP and the Foundation has massively promoted TTIP. This role should not have been authorised so soon after Reding left the Commission.

We have additional concerns that Reding holds these paid roles as a sitting MEP, particularly as she is part of the Parliament's trade committee and currently acting as rapporteur on a report to make recommendations on the negotiations for the very controversial Trade in Services Agreement or TiSA. The MEP Code of Conduct should be urgently reformed to prevent MEPs from holding certain second jobs, including consultancies, lobby jobs and paid directorships.

We contacted Viviane Reding prior to publishing this report; no response was received. More information: http://corporateeurope.org/revolvingdoorwatch/cases/viviane-reding or in our spreadsheet.

Karel De Gucht (Belgium)

Karel De Gucht (Belgium)

Old roles: Commissioner for Trade (2010-2014); Development and Humanitarian Affairs (2009-2010)

New roles: Member of the management boards of Belgacom (now known as Proximus); Merit Capital NV; CVC Partners; and other roles

De Gucht is the former EU Commissioner for Trade, and has been criticised by civil society for the way he consistently put big business in the driving seat of EU trade negotiations. He now has Commission authorisation to join the management boards of three different companies: telecoms company Belgacom, and two operating in the financial sector.

The Ad hoc Ethical Committee was not consulted by the Commission about De Gucht's move to Belgacom; the Commission decided that the activity was not related to De Gucht's former Commission portfolio. And yet, while De Gucht did not directly regulate telecommunications in his Commission role, he led on the negotiations for TTIP which has been of growing interest to the telecommunications sector. Belgacom (which now operates as Proximus and also owns digital media company Skynet) is the biggest telecoms operator in Belgium and a member of the lobby group European Telecommunications Network Operators' Association (ETNO). ETNO and Skynet lobbied EU trade officials on TTIP in meetings behind closed doors when De Gucht was Trade Commissioner. The telecoms/ IT sector was the third biggest lobbyist on TTIP in the two years to February 2014 (while De Gucht was still at the Commission), meaning it had the third largest number of behind-closed-doors meeting with DG Trade. Proximus is in the EU lobby register and has already spent €299,999 on lobbying this year (January-July 2015).

In our view, the Commission should not have authorised this move. It was wrong that the Ad hoc Ethical Committee was not asked to consider this case, and the standard 18 month direct lobby ban would not be sufficient to prevent the risk of possible conflicts of interest of De Gucht, a former trade commissioner, joining the board of Belgacom/ Proximus.2

By contrast, the Ad hoc Ethical Committee was asked to consider De Gucht's move to CVC Capital Partners, apparently the third biggest private equity and investment advisory company in the world. The committee rejects the possibility of a conflict of interest because De Gucht's former role only involved legal frameworks for trade and investment. Again, De Gucht's wider role as an EU commissioner during the devastating global financial crisis is not taken into account. Only the Commission's Legal Service asked for the standard 18 month lobby ban to be specifically included in the authorisation decision.

De Gucht states that this role was unremunerated but further information is redacted. The Ad hoc Ethical Committee writes: “The Committee notes that the envisaged activity will be non-remunerated but that Mr De Gucht may [redaction]”. The Commission says the redacted text refers to “contractual private data” but if it referred to other non-monetary benefits accruing to De Gucht from this role, the information should not have been removed. Whether or not a role is remunerated is a major (although not the only) factor when considering revolving door moves. Whatever the case, in our view, ex-commissioners should not be able to join the board of financial companies so soon after leaving office.

De Gucht has also received authorisation to join the board (unpaid) of Merit Capital, an independent private bank and stockbroker based in Antwerp but with additional offices in Deurle, Hasselt, Kortrijk and Leuven, as well as Zürich. De Gucht's Commission declaration of financial interests of 28 March 2011 indicates that he was previously a member of the board of directors of Merit Capital Group (formerly Sequoia International) prior to joining the Commission. During his time at the Commission, he retained a substantial shareholding; his 2014 declaration said that he owned an "usufruct" proportion of 744,700 Merit Capital shares, estimated to be worth €1,900,474.

Merit Capital is not in the EU lobby register. However, Merit is active in Belgisch Financieel Forum, as well as the Belgian Corporate Finance Association, and it is a member of Febelfin, the main Belgian financial lobby group. Febelfin explicitly states that they are doing EU lobbying for their members and Febelfin is part of the European Banking Federation which is very active at the EU level.

We contacted Karel de Gucht prior to publishing this report; no response was received. More information: http://corporateeurope.org/revolvingdoorwatch/cases/karel-de-gucht or in our spreadsheet.

Neelie Kroes (Netherlands)

Neelie Kroes (Netherlands)

Old roles: Commissioner for the Digital agenda (2010-2014); Competition (2004-2010)

New roles: Special Advisor to Bank of America Merrill Lynch; Board member of the Open Data Institute; and others

Neelie Kroes has several new roles, including acting as Special Advisor to the Bank of America Merrill Lynch (Europe, Middle East, Africa). The Commission authorised this role, after consulting the Ad hoc Ethical Committee, but we have several concerns about this.

As the committee notes, Kroes describes the role in very general terms: the only specific topic she mentions is “female leadership” and as she told the Commission, was likely to take the form of “sharing experiences, insights and exchanging perspectives”. She added: “More concretely for my role as an advisor, this means I could be requested to contribute to conferences and engaging politicians and thought leaders.” But engaging “politicians and thought leaders” sounds very much like it could entail lobbying. Her email also refers to strengthened “client engagement”. Kroes should have been asked to provide further clarification about what any of this might entail.

Kroes was told to avoid direct lobbying on behalf of BoAML for 18 months, but no mention was made of its clients or of indirect lobbying. For another of her roles, as unpaid board member of the Open Data Institute (a non-profit organisation which promotes “innovation”), Kroes was told to ensure that “that no company using the services of the Open Data Institute could unduly benefit from the knowledge and expertise she had gained during her terms of office”. It seems inconsistent and an omission not to have insisted upon a far wider lobby ban on Kroes' BoAML role.

Furthermore, Kroes was a European commissioner during the entire span of the financial crisis; we question whether it is appropriate for her to join a major bank with European interests, in any capacity, so soon after leaving the Commission. Afterall, BoAML spent over €1,250,000 in 2014 on EU lobbying (up from only €50,000 in the previous year, according to the LobbyFacts archive), on a wide range of EU dossiers.

Kroes originally joined the Commission in 2004 amidst claims of possible conflicts of interest relating to her then 25 corporate roles. Presenting herself to the Parliament for her confirmation hearing, she promised at the time that “she would not to return to the private sector once her term as Commissioner for Competition had expired”.

We attempted to contact Neelie Kroes via BoAML prior to publishing this report; no response was received. More information: http://corporateeurope.org/revolvingdoorwatch/cases/neelie-kroes or in our spreadsheet.

Siim Kallas (Estonia)

Siim Kallas (Estonia)

Old roles: Commissioner for Transport (2010-2014); Commissioner for Administrative Affairs, Audit and Anti-Fraud (2004-2010); Commissioner for Economic and Monetary Affairs (2004-2004)

New roles: Consultant for Nortal (terminated); Special Adviser to Commissioner Dombrovskis; Chair of Commission's High Level Group of Independent Experts on European Structural and Investment Funds; and others

The Commission authorised the appointment of Siim Kallas as a consultant to Nortal to “participate in projects promoting good governance practices in countries outside EU” on the condition that he refrained from lobbying the Commission and/or its services, for Nortal, during 18 months after the end of his mandate. Nortal is perhaps the biggest IT services company in the Baltic region and its clients include those from the public and private sectors in the oil, banking, telecoms, and manufacturing sectors.

This case was not referred to the Ad hoc Ethical Committee because there was no perceived link with Kallas' former transport portfolio. However, when Kallas applied for authorisation for this role (28 March 2015), he was already acting as Special Adviser to Commissioner Valdis Dombrovskis on the issues of “Strategic and political advice on future of EMU, economic relations with Eastern neighbourhood”. An adviser on economic relations with the EU's eastern neighbourhood could have links and/or overlaps with consultancy aimed at finding Nortal some new clients in countries outside EU. In our view, there is a fine line between offering advice to a commissioner and lobbying; but as far as the Commission is concerned, the former is allowed and the latter is apparently not.

As no reference is made to Kallas' additional role of special adviser (he does not raise it and the Commission paperwork does not mention it either) it appears that this element was not fully explored. This is a serious omission and shows the limitations of the revolving doors process as conducted by the Commission (led by the Secretariat-General, with inputs from the Legal Service), looking at new roles on a case by case basis, rather than looking at the overall portfolio of a former commissioner's new roles.

Special adviser rules and procedures may also need looking at. The declaration of activities signed by Special Adviser Kallas released under access to documents had not been updated to mention his new work for Nortal. Following a CEO complaint about this matter, the Commission has told us that Kallas has now updated his declaration.

We contacted Siim Kallas prior to publishing this report. In September 2015 he told us that,

“In June I had some speeches in Oman about Estonian experience of good governance. This was intended to help IT company Nortal to sell their IT solutions in this country. These activities have nothing to do with my role as advisor to Mr. Dombrovskis. My contract with Nortal was terminated as from the 6th of August 2015, about what I informed the European Commission. I have never lobbied for Nortal in European institutions.”

Notwithstanding Kallas' short tenure with Nortal, the Commission should not have authorised this role.

More information: http://corporateeurope.org/revolvingdoorwatch/cases/siim-kallas or in our spreadsheet.

José Manuel Barroso (Portugal)

José Manuel Barroso (Portugal)

Old role: President of the European Commission (2004-2014)

![]()

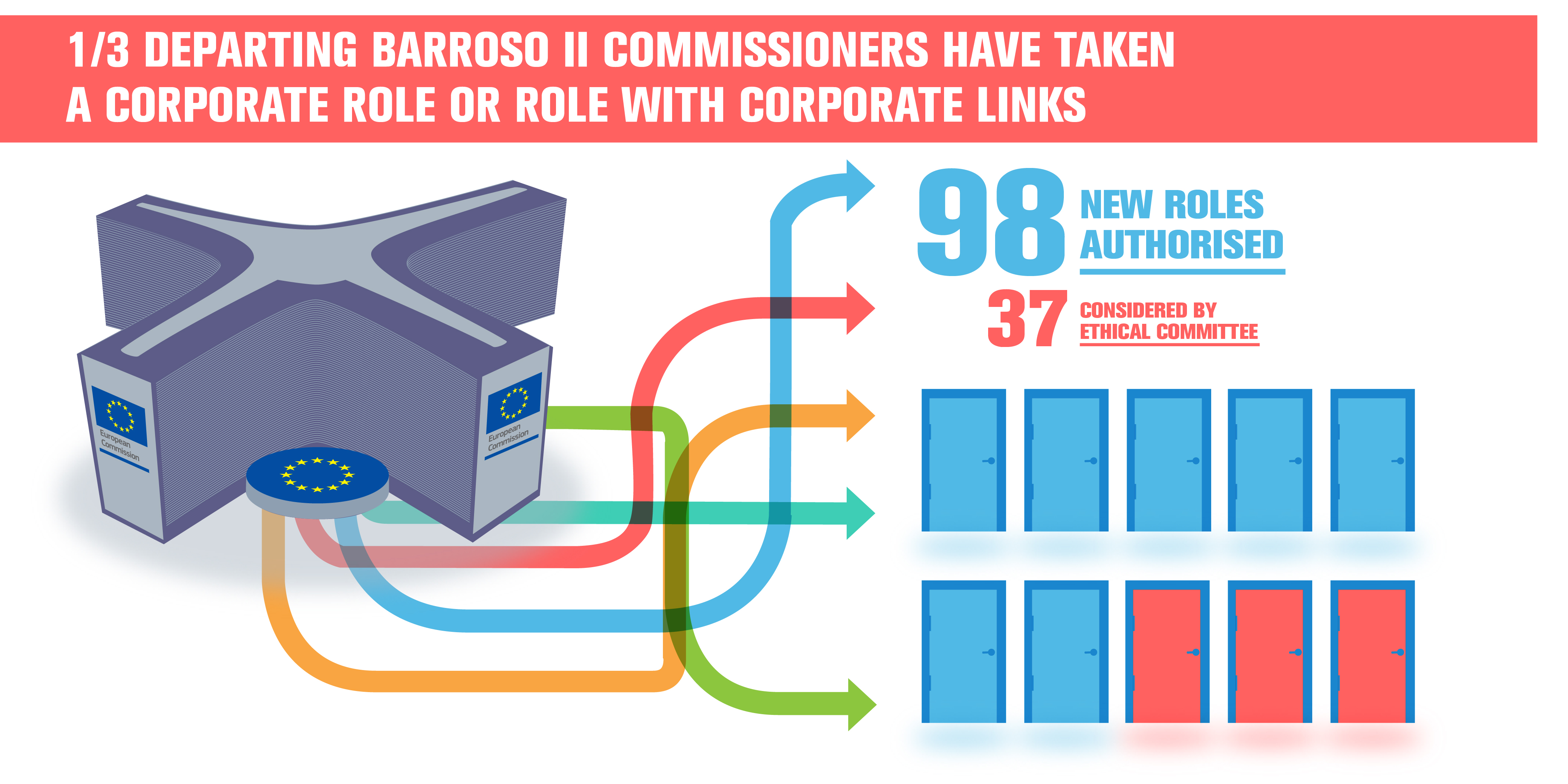

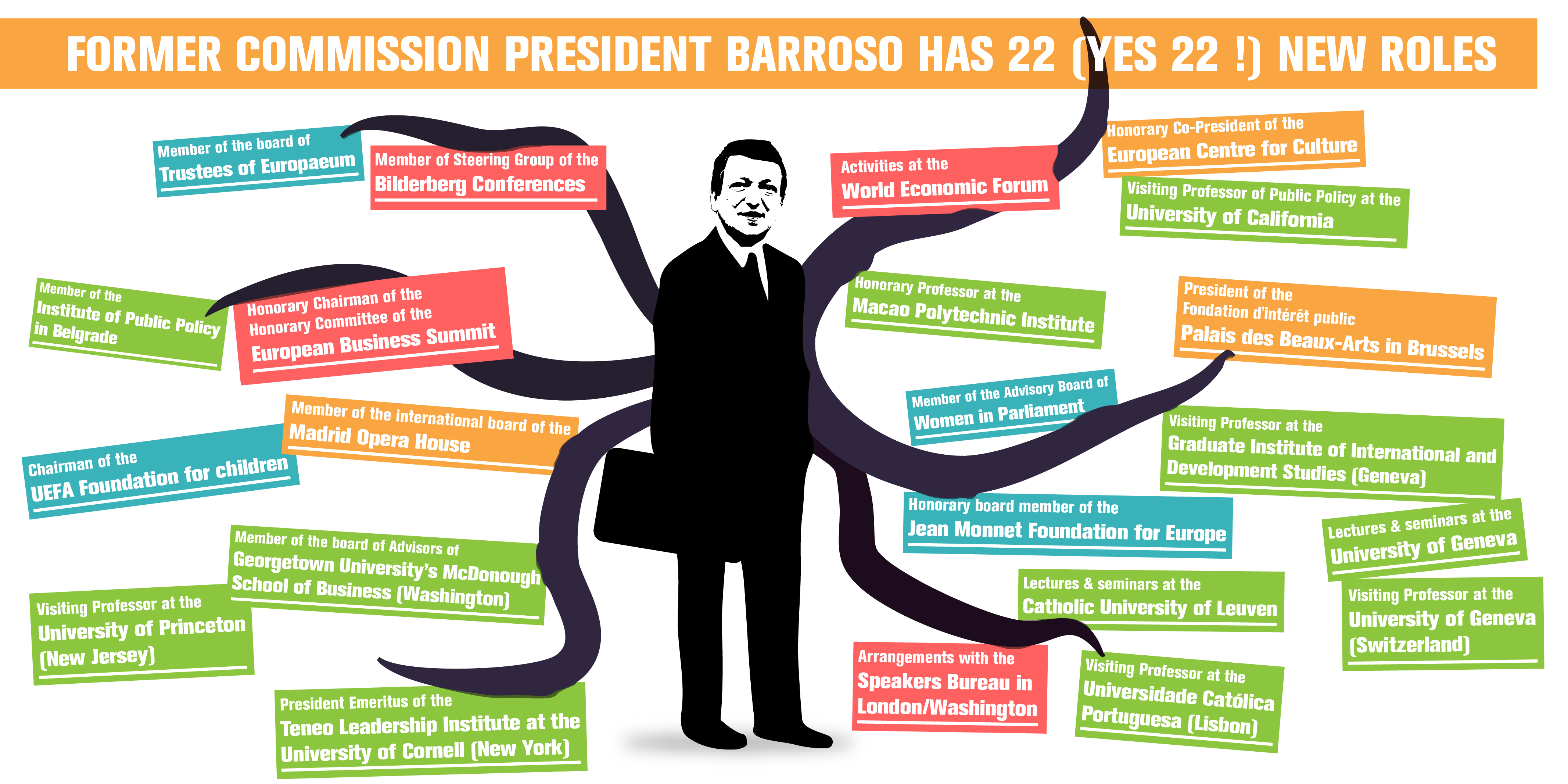

New roles: Member of Steering Group of the Bilderberg Conferences; Honorary Chairman of the Honorary Committee of the European Business Summit; and others

José Manuel Barroso has accepted, and been authorised in, 22 new positions, including ten in the academic world, plus roles in the arts, for think tanks and with speakers' bureaux. Many, although not all of these, are unpaid or honorary positions.

However, a number of his new roles raise questions as to how they were handled, including his membership of the steering group of the Bilderberg Conferences; and his role as Honorary Chairman of the Honorary Committee of the European Business Summit. These are unpaid roles and the Bilderberg role was passed to the Ad hoc Ethical Committee for an opinion. However, we are not clear how much consideration there was about the nature of the Bilderberg conference. In particular, there appears to have been little reflection on the fact that as reported by The Guardian last year: “Bilderberg is packed to the gills with senior members of powerful lobby groups” and is “big business. And big politics. And big lobbying”. It seems a strange omission not to have reminded Barroso about the ban on lobbying in the context of his Bilderberg role.

Meanwhile, the Commission did not consider that it even needed to formally authorise Barroso's new role at the European Business Summit, due to its honorary nature, despite the EBS being the largest business lobby event in the Brussels bubble calendar. It simply accepted having been notified of the role. But what does being Honorary Chairman of the Honorary Committee actually mean? Is it having your name and photo on the website, or something more? Does the committee meet in person? The Commission never clarified this. By contrast, it did go through a formal authorisation process for Barroso's new role as an (unpaid) member of the international board of the Madrid Opera House!

It is not always possible to understand the rationale of the Commission in its handling of these roles: which ones they consider require active authorisation or not, and which are passed to the committee for an opinion, or not. For the sake of clarity and transparency, in our view all new roles, unpaid and paid, and whether 'honorary' or not, should be authorised.

We contacted José Manuel Barroso via the University of Princeton prior to publishing this report; no response was received. More information: http://corporateeurope.org/revolvingdoorwatch/cases/jos-manuel-barroso or in our spreadsheet.

A few other cases of note:

Joaquín Almunia (Spain)

Joaquín Almunia (Spain)

Among the 13 roles for which ex-Competition Commissioner Joaquín Almunia has received authorisation is as a paid member of the 'scientific committee' to produce the study 'Building the European Energy Union' by the European House-Ambrosetti. The latter is a for-profit consultancy based in Italy and its board includes senior staff from Enel, ING bank, JP Morgan and others. In fact the Energy Union study was “requested” by (and is presumably funded by) Enel, the major Italian multinational operating in the power and gas markets. Enel has its logo on the study and shares the copyright; the advisory board for the study included several Enel staff including Francesco Starace, the Chief Executive, and Simone Mori, Head of European Affairs, plus three other staffers. Commissioning third parties to undertake research and policy work in an area where they wish to boost their strategic influence is a common way for corporations to promote their agenda.

Almunia's own preface to the report talks about how to improve competitiveness: “We need to achieve the single market for electricity and gas, through interconnections, common regulations and adequate incentives for investors.” This implies that we need to build new infrastructure for fossil fuels which locks us into long-term use, while “incentives for investors” means public money to “leverage” ie subsidise dirty energy / infrastructure companies to help achieve this. While the report supports the move to decarbonisation of the EU's energy system by 2050, its policy recommendations appear to be more in tune with Enel's interests and include a single market for energy (which would make it easier for big energy companies to operate across borders), and a stronger emissions trading scheme.

Enel is a major EU lobbyist spending over €2,000,000 in 2014. Since December 2014, Enel has met top officials in the Commission at least eight times (according to IntegrityWatch), including a meeting with Vice-President Maroš Šefčovič who is responsible for the EU's Energy Union.

When the Commission was asked to authorise this role, the Ad hoc Ethical Committee said the study may “provide a useful contribution to EU endeavours”. The Commission approved Almunia's paid role in this study as long as he did not “favour the commercial interests of the companies involved”. But this is rather meaningless considering that Enel commissioned, and likely paid for, the study and has its logo all over it. The Commission should have taken a far more sceptical view about this role and the automatic benefits likely to accrue to Enel from having an ex-commissioner endorsing the study. Almunia did not respond to CEO's questions.

Maria Damanaki (Greece)

Maria Damanaki (Greece)

Maria Damanaki the former Commissioner for Maritime Affairs and Fisheries (2010-14) has been authorised to accept one new role as Global Managing Director for Oceans for The Nature Conservancy (TNC), a US-based NGO. The Nature Conservancy publicly announced its recruitment of Damanaki one month before the role was authorised by the Commission, something which the rules should clearly forbid. Twice Damanaki was asked to provide further information about her precise role at TNC and the nature of its activities in Europe. Ultimately, she was authorised to accept the role provided that she “abstained from lobbying the Commission and its departments on any issues with a potential link to her former portfolio... for 18 months after leaving the Commission”.

TNC was one of several NGOs criticised by Naomi Klein for its links to fossil fuel companies. The board of directors of TNC is full of people with corporate roles including Goldman Sachs, Google, Alibaba group, Blackstone Group, and many others. TNC's Vice Chair is James E Rogers, the retired Chairman, President and CEO of Duke Energy; the head of TNC, Mark Tercek, is a former Managing Director and Partner at Goldman Sachs, where he worked for 24 years.

In our view, the Commission should have applied a far lengthier and broader lobby ban, with specific reference to those corporations with funding or governance links to the TNC. Even if Damanaki does not directly lobby the Commission for 18 months, she is clearly a high-profile and well-connected individual and she would be able to provide substantial advocacy advice (indirect lobbying) to her new employer. It should also have seriously considered whether it was even appropriate for Damanaki to take such a role which is so closely associated with her previous portfolio, at an organisation so close to corporate interests, soon after leaving office. We contacted Maria Damanaki; she told us that there were no overlaps between her old role and the new one and that there was no basis for concerns about conflicts of interest; her full response can be read here.

More information: http://corporateeurope.org/revolvingdoorwatch/cases/maria-damanaki or in our spreadsheet.

Janez Potočnik (Slovenia)

Janez Potočnik (Slovenia)

Among the new moves of former Environment Commissioner Janez Potočnik is Chairman of the Forum for the Future of Agriculture, which is the creation of the European Landowners' Organisation and Syngenta. Syngenta is one of the world's largest pesticide companies; in the EU lobby register it declares a 2014 lobby budget of €1,250,000-€1,499,999. In 2011, CEO wrote of the fourth Forum for the Future of Agriculture: “What was announced as a 'meeting place for those who have a stake in the future of agriculture' was in fact a tightly orchestrated lobbying event for Syngenta to polish its image and promote its agenda for the reform of EU agricultural policies.” The Commission authorised this move so long as Potočnik's involvement excludes anything that could be related to the commercial interests of Syngenta. It is hard to understand what this means in practice, considering that the Forum for the Future of Agriculture is a lobby event promoting the interests of agribusiness corporations representing their own agricultural model. When asked by CEO, Potočnik told us that:

"I was as Commissioner for Environment participating quite regularly on FFA since I have believed, and I still do so, that this is one of the best opportunities to prepare agricultural community to necessary changes arising from the need to respect sustainability."

More information: http://corporateeurope.org/revolvingdoorwatch/cases/janez-poto-nik or in our spreadsheet.

Algirdas Šemeta (Lithuania)

Algirdas Šemeta (Lithuania)

Algirdas Šemeta, the former commissioner for taxation and customs union is now the new Ukrainian Business Ombudsman. This role forms part of Ukraine's anti-corruption initiative and involves the Ukrainian Government and business associations including the American Chamber of Commerce in Ukraine, the European Business Association, the Federation of Ukrainian Employers, the Ukrainian Chamber of Commerce and Industry, and the Ukrainian League of Industrialists and Entrepreneurs. The Commission's Ad hoc Ethical Committee decided that the position of Ukraine Business Ombudsman was “essentially one of independent service in the public interest”, but we were very surprised that Šemeta was not even reminded of the standard 18 month lobby ban, considering its links with business interests. We tried to contact Šemeta via twitter and facebook but no response was received.

More information: http://corporateeurope.org/revolvingdoorwatch/cases/algirdas-emeta or in our spreadsheet.

Štefan Füle (Czech Republic)

Štefan Füle (Czech Republic)

Štefan Füle is the former Commissioner for Enlargement and European Neighbourhood Policy 2010-2014 and is now a member of the think-tank, the Central European Strategy Council’s International Advisory Board; according to information from the Commission (as of 7 August 2015) he has not sought authorisation for this role. The CESC aims to “strengthen the voice of Slovakia and Central Europe in European and global affairs” by connecting “key Central European personalities and experts in foreign and security policy”. The Code of Conduct for Commissioners says that serving commissioners can hold “honorary unpaid posts in political, cultural, artistic or charitable foundations or educational institutions”; presumably these roles for former commissioners do not require notification or authorisation. And yet, many other former commissioners have notified such unpaid roles, and some have been through a formal authorisation process too. Arguably there is a link between this role and Füle's former role as Commissioner for Enlargement and European Neighbourhood Policy. We think all such roles should go through a formal authorisation process. We tried to contact Füle via the Central European Strategy Council but we received no reply.

Conclusions

In September 2014, a research report written for the European Parliament concluded that:

“Overall, the [Commissioners' Code of Conduct] is characterised by its poor checks and balances, the absence of a coherent implementation system, and opacity surrounding its operation (eg with regard to the Ad hoc Ethical Committee). Whilst other ethics systems contribute to enhance public trust in government, the EC’s system appears tilted towards the Commissioners’ political and career interests”.

We couldn't agree more and it is time for an overhaul of the ethical rules for commissioners, including for after they leave office, as suggested below (and further detailed in the annex):

|

Overall, there needs to be a far more rigorous and, dare we say, sceptical, approach taken to the revolving door, especially as it affects the EU's most senior leaders, so as to ensure that experiences and insights gained from years of working at the highest levels of public office do not end up benefiting private, corporate interests.

The case for reform is compelling, although it is likely too late to impact upon the former Barroso II commissioners. So the question is whether Jean-Claude Juncker's College of Commissioners are prepared to vote to toughen up the rules for when they themselves eventually leave office. We are not holding our breath.

Annex: Existing rules and proposals for change

In this annex, we present the existing rules and present an in-depth analysis of how they should be changed.

1. What are the revolving door obligations on former commissioners?

According to the Code of Conduct for Commissioners the rules are as follows:

- For 18 months after leaving office, a commissioner intending to engage in an “occupation”, shall inform the Commission.

- The College of Commissioners ultimately decides whether or not to authorise a role (and whether to place any limits or restrictions on it) based on its compatibility with EU treaty article 245 which gives former commissioners a duty “to behave with integrity and discretion as regards the acceptance, after they have ceased to hold office, of certain appointments or benefits”.

- When the occupation is related to the commissioner's former portfolio, the Commission is obliged to seek advice of the Ad hoc Ethical Committee. When cases are not referred to the committee, the Commission's Secretariat General develops a proposal for authorisation, upon which the Legal Service is consulted.

- The rules ban all former commissioners for 18 months after leaving office, from lobbying the Commission on behalf of business, clients, employers on matters connected to their previous portfolio.

- The rules say that public office roles need to be notified to the Commission, but do not need formal authorisation.

- The rules make clear that commissioners have an ongoing duty, beyond the 18 months after they have left office, to behave with integrity and discretion.

Former commissioners are also entitled to a generous transitional allowance for three years, of between 40 per cent and 65 per cent of the final basic salary, depending on the length of service. The allowance is capped; if a former commissioner takes up any new gainful activity, the new pay added together with the allowance, cannot exceed their former remuneration as a member of the Commission. Since July 2012, the basic gross salary of a commissioner is €20,832 per month; the President earns €25,554. The net average salary across the EU is €1470 per month.

2. Composition and Tasks of the Ad hoc Ethical Committee

The Ad hoc Ethical Committee consists of a trio of ex-EU institution insiders (currently a former Commission director-general, an ex-MEP, and an ex-EU judge), tasked with providing an opinion to the Commission on the compatibility of former commissioners' proposed new roles with their obligations under the EU treaty. The remit of the Ad hoc Ethical Committee is limited. It can only consider the cases that are referred to it by the Commission, and the Commission only hands over cases where a proposed new role is considered to have a link with the commissioner's former portfolio or another specific concern. The committee can only give an opinion or make a recommendation; it is not a decision-making body.

The committee was embroiled in a major scandal in 2012-13 when the then Commission President Barroso decided to re-appoint Michel Petite as the committee's Chairman. Petite had had a controversial spin through the revolving door himself from the Commission's Legal Service to global law firm Clifford Chance in 2008 where his clients have included tobacco firm Philip Morris. Petite has also carried out lobbying vis a vis the Commission. Following an NGO complaint, the European Ombudsman wrote to Barroso recommending that Petite be replaced; soon after he 'resigned' and was replaced. The Commission has yet to admit any wrong-doing in this debacle.

3. Detailed analysis of necessary changes to the Code of Conduct for Commissioners

3.1 Conflicts of interest and lobbying

- The current Code of Conduct for Commissioners is far too vague to provide an adequate framework for the assessment of whether former commissioners' proposed new roles are appropriate. Article 245 of the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union (TFEU) which gives former commissioners a duty “to behave with integrity and discretion as regards the acceptance, after they have ceased to hold office, of certain appointments or benefits” is very subjective and unclear. Moreover the phrase “conflict of interest” does not appear within the revolving door rules at all.

- Considering this, it is perhaps not surprising that all proposed Barroso II Commission roles put before it, have been authorised by the College of Commissioners (Commission information to 1 October 2015). Additionally, in no case has the Commission implemented tougher restrictions than those set out in the Code of Conduct. In our view, all former commissioners should be explicitly forbidden from accepting any new role which risks creating a situation of a conflict of interest with their former role as a European commissioner for three years after their departure. This should be accompanied by a comprehensive explanation of what this means (perhaps with reference to the OECD's guidelines in this area).

- There are further flaws within the Code of Conduct for Commissioners, compounded by the lack of definition of key words and phrases. The word “occupation” is unclear: does that mean only paid work, or unpaid roles too? Lobbying is also not explicitly defined, but it appears to be limited to direct lobbying: sending emails and letters to the Commission; or making calls and holding meetings with former colleagues. Indirect lobbying ie providing advice to new colleagues on the best way to approach the Commission, based on the insights and network gained as a former commissioner, does not seem to be included and this represents a major loophole in the rules.

- The lobby ban for former commissioners needs to be toughened up. The ban on lobbying should be extended to a full three years and it should explicitly cover both direct and indirect lobbying. If there is any likelihood that a new role could involve lobbying, the role should be rejected altogether, rather than restrictions being placed on the lobbying component.

- As outlined above, in the cases of De Gucht, Kroes, Reding and others, we feel it is too limited to restrict the lobby ban to issues related to former commissioners' most recent portfolio. Commissioners are high-profile and influential individuals who, as part of the college, take many collective decisions on a wider range of issues over a period of years. In this case, the lobby ban should be absolute and cover all issues. It should also be expanded to cover the lobbying of all EU institutions, not just the Commission.

3.2 Notification and / or authorisation

- The current Code of Conduct is too limited in determining which roles require authorisation, which require only to be notified to the Commission, and when the Ad hoc Ethical Committee should be asked to provide an opinion, and it has led to some strange decisions.

- The Code of Conduct says that serving commissioners can hold “honorary unpaid posts in political, cultural, artistic or charitable foundations or educational institutions”. Honorary is interpreted as no management role, no decision-making power, and no responsibility or control of operations. The revolving door section of the rules does not explicitly refer to such roles, so presumably these role fall outside of the rules and do not requite notification or authorisation. A range of roles have been classed in this category and accepted as notified but not requiring authorisation. But in some cases, we have questioned that decision. Surely when former Commission President Barroso accepts a role with Brussels' biggest corporate lobbying event, the European Business Summit, it should go through a formal authorisation process?

- Also, Štefan Füle is now a member of the Central European Strategy Council’s International Advisory Board and, as of 7 August 2015, he has not been in touch with the Commission about this role. The Code of Conduct for Commissioners says that serving commissioners can hold “honorary unpaid posts in political, cultural, artistic or charitable foundations or educational institutions”. Honorary is interpreted as no management role, no decision-making power, and no responsibility or control of operations. The revolving door section of the rules does not explicitly refer to such roles, so presumably these roles do not require notification or authorisation. And yet, many other former commissioners have notified such unpaid roles, and some have been through a formal authorisation process. Arguably there is a link between this role and Füle's role as Commissioner for Enlargement and European Neighbourhood Policy.

- We consider it would be far better to avoid any confusion by ensuring that all new roles (paid or unpaid, 'honorary' or not, public office or not) should be formally notified to the Commission, and should go through an authorisation process.

3.3 Transparency

- Currently, the only way to get the concrete details of former commissioners' new moves involves scrutiny of Commission minutes to find such decisions, followed by access to documents requests to obtain the paperwork. This is inefficient for both the Commission (who have privately expressed their frustration to us about the volume of our access to documents requests on these issues) and for those of us who wish to scrutinise the new roles. It is also not effective transparency. The European Ombudsman has recently suggested that there should be full transparency about all former commissioners' revolving door moves, via a dedicated website which publishes information along the lines of that in our spreadsheet. We echo that demand, and if the information is already releasable under access to documents, the information should be pro-actively published by the Commission so it can be easily accessed by citizens and watchdog groups. Moves which have been notified to the Commission but which do not need formal authorisation under the current rules (ie public office) should also be included. Cases where new roles were considered and ultimately rejected for authorisation should also be made transparent.

- The Commission has so far refused to provide any further information on three requests for authorisation that were subsequently withdrawn by the former commissioners concerned: Connie Hedegaard (one role) and Androulla Vassiliou (two roles). Vassiliou has told us that “the Ad Hoc Ethical Committee's opinion was that there might have been a conflict of interest, I respected their opinion and I rejected the two offers without proceeding with an application to the Europ. Commission. As I rejected the two offers, the matter is considered closed.”

- A similar process led to Barroso I commissioner Charlie McCreevy eventually withdrawing an application to join the board of a bank in 2009-10 having seen the (negative) recommendation of the Ad hoc Ethical Committee, and after an email exchange with the then Secretary General, but before the College was requested to make a final decision. We consider that all opinions of the Ad hoc Ethical Committee should be made transparent in all cases considered.

3.4 Independence of the committee

- According to our database, only 35 out of 96 authorised cases have been referred to the Ad hoc Ethical Committee. No formal capacity and resources are allocated to the committee to help it to do its work, although the Commission has told us that the committee can “request the Commission to provide the additional information that they consider necessary”. If a request for authorisation has not been passed to the committee, the Commission's own services (the ethics unit within the Secretariat General) produce a recommendation for the ultimate decision-maker, the College of Commissioners. As far as we are aware, the college has yet to dissent from any recommendation provided to it on a Barroso II revolving door move.3 The college's meeting minutes do not reveal the extent of discussion and debate when the college takes a decision on one of these cases, but it is not hard to imagine that it plays a 'rubber stamp' role, simply endorsing what is recommended to it. It is therefore very important that the advice provided is of the highest quality. This is why we think that the present system should be overhauled.

- The current Ad hoc Ethical Committee should be abolished and replaced with a fully independent ethics committee made up of experts drawn from member states' ethics and administration systems with no links to the EU institutions. This independence is important. In our view, the EU institutions are not as vigilant as they should be about the risk of conflicts of interest arising from the revolving door. Current commissioners, staff and ex-EU insiders should not formulate advice or make decisions on their contemporaries' proposed new roles; there is a risk that residual loyalties might skew the process. Additionally, it is not appropriate to ask those who might wish to spin through the revolving door in the future, to advise or make decisions on others' revolving door moves today.

- Arguably the current Code of Conduct rules placed President Barroso in a situation of a conflict of interest when he handled the revolving door roles of his former colleagues. On 9 September 2014, former commissioner Viviane Reding wrote to Barroso to seek authorisation to join the Bertelsmann Foundation. Meanwhile, on 9 October 2014 while still president, Barroso himself wrote to Catherine Day, the Secretary General to request authorisation for his own plans for post-office activities, including at the World Economic Forum. A fully independent committee would (help) resolve this problem.

- The fully independent committee should be supported by a well-resourced secretariat with investigative powers. This would enable further research and checking to take place, ensuring that former commissioners' assertions are not the only evidence used when formulating a recommendation. It could also help with post-authorisation monitoring (see below).

- The new independent ethics committee should be responsible for all former commissioners' new roles – paid and unpaid – and its work and recommendations should be fully transparent. It should be proactive, rather than waiting for issues to be referred to it. Its remit could be further expanded to all matters concerning ethics and conflict of interest regulations, policies, codes applying to Commission staff and commissioners, and their implementation and enforcement, with the aim of promoting high ethical standards and best practice. This would help introduce joined-up thinking in cases like that of Siim Kallas who has had multiple and simultaneous roles and obligations, as a former commissioner, a current Commission special adviser, and a (former) private sector consultant. The independent ethics committee, supported by a resourced secretariat, should also be responsible for monitoring that the rules and any specific conditions placed upon new roles, are abided by.

3.5 Consistent application of the rules

- The way in which former commissioners are informed about the authorisations of their new roles and their ongoing obligations varies significantly. Sometimes, former commissioners have been reminded about their obligations under Article 245 of the EU treaty “to behave with integrity and discretion” and to follow the “obligation of professional secrecy”. Article 245 applies equally to all commissioners; so why not remind them of that equally?

- And the lobby ban is handled differently from case to case. It seems a major omission not to have even mentioned the standard lobby ban in the case of former commissioner Algirdas Šemeta in his role as Ukrainian business ombudsman, a role set up and paid for by business interests in Ukraine. In fact this role was authorised without any reminder at all, let alone any added restrictions.

- In our view, a fully independent ethics committee and secretariat which is responsible for the whole authorisation process of former commissioners' new roles, combined with proactive transparency in this area, could really help to improve the consistency with which these cases are handled.

3.6 Transitional allowance and authorisation period for new roles

- In theory, the transitional allowance ensures that former commissioners do not need to rush to find a new job for financial reasons after leaving the Commission, and thus risk a possible conflict of interest. By all calculations, the transitional allowance for former commissioners is very generous, and if former commissioners are to have such an entitlement for three years, it is right that they have ethical obligations for the same length of time. However, it is highly problematic that former commissioners' entitlement to the allowance (three years) exceeds their formal obligation to seek authorisation for new roles (eighteen months), and that it is possible to earn both a new salary and the allowance simultaneously. Former commissioners already have a three-year obligation to notify the Commission about their other sources of income so that any necessary reduction can be made to the transitional allowance due. It would be a very easy change to extend the period during which commissioners should seek authorisation for new roles from eighteen months to three years.

- However, it should also be the case that the Code of Conduct for Commissioners applies to all commissioners whether or not they accept the transitional allowance. A former commissioner who rejects the transitional allowance, or who draws their Commission pension rather than the allowance, or chooses to earn such a large sum from a third party that she loses her entitlement to the allowance, should still be covered by the revolving door rules in the Code of Conduct.

1 Reding has received Commission authorisation to join the board of Nyrstar, but has yet to do so.

2To date, De Gucht has not been appointed to the board of Proximus although newspaper reports in September 2015 indicated that the move had now been approved by the Belgian Government (Proximus is 53 per cent owned by the Belgian state); it now requires authorisation by the Proximus board.

3 For the Barroso I Commission authorisations in 2009-2010, on one occasion the College of Commissioners dissented from the opinion of the Ad hoc Ethical Committee when it voted to authorise a consultancy business already set up by former commissioner Günter Verheugen; the committee had not approved that role.

This report is jointly published with LobbyControl

Comments

I am a university lecturer and teach among other subjects, Industrial Economics, including topics like, "Regulation", "Moral Hazards", "Incentives" etc. Next term I will have this course (January 2016), I will encourage my students (most of them are Erasmus Exchange students) to study carefully this rapport, to find out that the modern theory of "capture" fits very well. In addition they will understand how "corrupt" our decision makers are.

I have a question, not as academic, just as a simple "tax-payer" European citizen who still believes in justice. Can't the European Parliament and/or the European Court of Justice take it seriously and start an immediate investigation, not only against those mentioned in the rapport, but also against "the Ethical committee"?

Best regards

Christos P.

cool Website-report. it would be worth (still today) to be layoutet and downloadable as *.pdf. The attached PDF is also just an Webprint-into-pdf (and in a poor quality, Graphics are missing etc.). It would really be worth