The EU Emissions Trading System might subsidise new coal plants in Greece. Wait, what?

Subsidies raised through the Emissions Trading System, the EU’s flagship policy to reduce climate change, could be the key to ensuring that two new coal-fired power stations are built in Greece, according to a recent report in The Guardian newspaper.

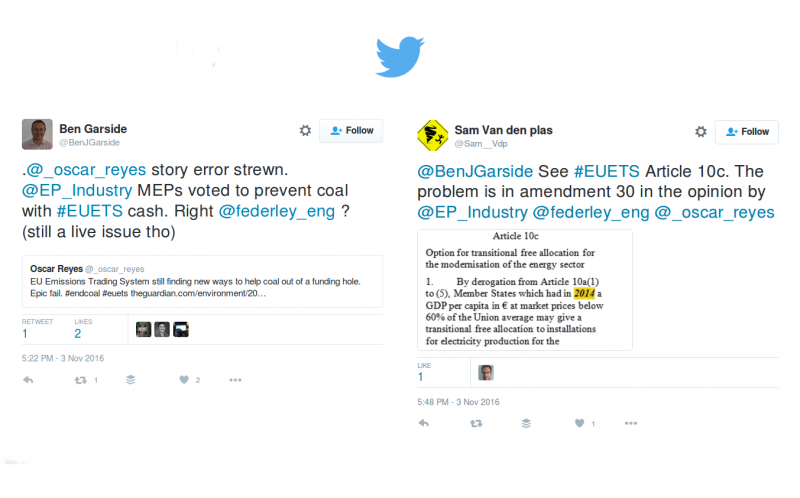

Yes, you read that right – although the claims made in the article seem so incredible that they were immediately questioned.

Back in 2009, the EU negotiated “a classic Brussels fudge” to get its carbon trading legislation passed: article 10c of the Emissions Trading Directive, which allowed central and eastern European states to continue handing out free pollution permits to big electricity producers (mostly burning coal) in those countries. This was accompanied by a condition that these countries invest at least the same amount of money in modernising their energy systems as the value of the permits they hand out for free.

What happened next revealed “modernisation” to be doublespeak for dirty energy subsidies, as most of the earmarked funds went into modernising coal-fired power stations and expanding these and other fossil fuel infrastructure. There were no rules to prevent this from happening. In Poland, the largest beneficiary from article 10c, over 80 per cent of the investment to modernise the energy system went to fossil fuel projects. These included significant financial support for a new lignite power plant that will become Poland’s largest. (Lignite is a form of coal that emits particularly high amounts of carbon dioxide when it is burned).

The current review of the EU Emissions Trading System is meant to replace this free-for-all with stricter rules on how the investments accompanying article 10c should be made, as well as introducing a new Modernisation Fund to support cleaner energy. But a lot of devils lie in the details of how “clean” is defined, and lobbyists are still working hard to introduce loopholes for fossil fuel funding.

When the European Parliament’s Industry, Research and Energy (ITRE) Committee delivered its Opinion on ETS reform last month, it included a proposal specifically designed to make Greece eligible for article 10c, allowing it to hand free pollution permits to its power sector (with lignite the source of around half of the country’s electricity)

While the EU owes Greece more than a few breaks after imposing devastating austerity, the placement of this particular amendment would serve to deepen the country’s dependence on coal.

The exact way this would work has led to some confusion, even amongst carbon market experts. On the one hand, the ITRE amendment rules out the possibility that a new Modernisation Fund could invest in “new coal-fired energy.” At the same time, though, countries covered by article 10c can continue (or start, in Greece’s case) to give free pollution permits to coal-fired power plants. And it’s that loophole that would allow the two new lignite plants in Greece to receive up to €1.75 bn worth of free pollution permits, according to estimates in The Guardian - shoring up their shaky economic rationale at a heavy cost to the climate.

There are several hurdles that the Directive still needs to pass (starting with the Parliament’s Environment Committee, which meets in early December) before this is written into EU law, but the risk of an ETS that continues to give a free pass to coal power is clear.

The case of the Greek coal plants highlights some deeper problems with the idea that emissions trading will direct funds towards an energy transition. Since the outset, the ETS has been far more effective as a means of subsidising polluters than it has as a way to control climate change. In the case of coal financing alone, aside from the article 10c debacle, the ETS was a major culprit behind a German “dash to coal”, with rules on free allowances creating a significant incentive for the building of new lignite plants in Germany.

At the same time, the ETS has consistently put a dampener on efforts to expand renewable energy – most recently, helping to undermine the case for robust renewable energy targets in each of the EU’s member states.

Revising the ETS over and over again does not lead to different results, because its basic premise remains the same: emissions trading creates a market in which the supply side is determined by political decisions, rather than related to demand. And behind those decisions lies a world of heavy lobbying and entrenched interests, where big polluters have a far stronger hand than the handful of environmental NGOs hoping for incremental changes to make the scheme better.