FleishmanHillard’s secret lobby campaign for Monsanto

Multi-million lobbying spending not declared to EU transparency register

Recent evidence supports widely held suspicions that much larger sums of money are spent by corporations on lobbying than they declare in their entries to the EU Transparency Register. A report by law firm Sidley Austin, published by Bayer, revealed details of a lobbying contract between lobby firm FleishmanHillard and Monsanto, now owned by Bayer, worth €14.5 million. This is many times the lobby spending declared by both companies in the register.

During 2016 and 2017, Monsanto had hired FleishmanHillard to compile for it a vast list of Monsanto’s opponents (the ‘stakeholder lists’). This activity was part of a wider lobbying campaign to secure a new licence for glyphosate, a key ingredient of the controversial weedkiller Roundup. The murky details of this lobby campaign began to be first reported publicly in French media in May 2019. Leaked documents showed how Monsanto had paid FleishmanHillard to – potentially illegally – compile and document information on critics of their chemicals and GMOs.

The list of critics was comprehensive, containing the names of some 200 people in France, including journalists and politicians, such as the French Environment Minister at the time, Ségolène Royal. Numerous official complaints were subsequently submitted to the French authorities by individuals on the list, for instance by staff at the daily newspaper Le Monde.

FleishmanHillard, whose offices are situated next door to Bayer-Monsanto, works for various polluting industries including chemicals, gas and biotech, and for mega-investor BlackRock. While only the French file was leaked, it was clear that the full list extended to various other EU countries and the Brussels level itself.

This story resulted in more bad news for Bayer-Monsanto, following the company’s annual meeting in April 2019 where shareholders revolted, and the mindblowing fine of €1.8 billion ordered by a California jury in one of the Roundup lawsuits.

Bayer was quick to apologise, and ditched FleishmanHillard in the days that followed. Sidley Austin, a law firm located a few blocks further away in Brussels, was hired to clean up the mess. Sidley Austin itself is not registered in the transparency register, despite the fact that it is clear that numerous law firms in Brussels frequently engage in lobbying activities for corporations.

Sidley Austin contacted all the people featuring on FleishmanHillard’s list, including two of Corporate Europe Observatory’s researchers. Apart from being labeled as “influencers”, no further details were recorded in the files, according to the information disclosed to CEO by the law firm.

On 5 September 2019, Bayer published Sidley Austin’s report and announced that there was nothing illegal about the tactics deployed by Brussels lobby firm FleishmanHillard on behalf of Monsanto. The report concludes:

“There is no question that the […] stakeholder lists created were detailed, methodical, and designed to strongly advocate Monsanto's positions to stakeholders and to the public. But […] we did not find evidence to support the French media's allegations regarding the illegality of the stakeholder lists.”

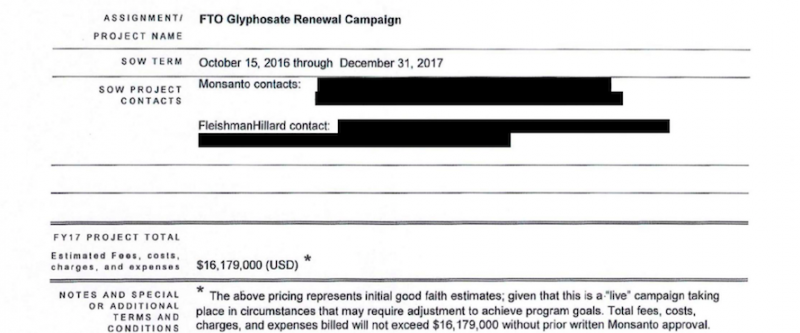

That remains to be seen. However, Sidley Austin report reveals some very interesting information on the so-called Glyphosate Renewal Campaign run by FleishmanHillard for Monsanto, from October 2016 to December 2017.

The Statement of Work between Monsanto and Fleishman-Hillard for the Glyphosate Renewal Campaign, which covered both the EU and the US, was worth a massive €14.5 million ($16.2 million).

Source: www.bayer.com

These figures contrast starkly with, and contradict, the submission of both companies to the EU Lobbying Transparency Register. FleishmanHillard stated that it was paid up to €800,000 in 2016 by Monsanto, at that moment its top client. Monsanto itself claimed that its total lobbying budget was at most €1.45 million between September 2016 and August 2017.

These figures show that the pesticide industry’s actual lobby firepower is and was far greater than is claimed publicly, and goes far beyond that of citizens’ movements or NGOs working on these issues. There is such discrepancy between the declared amounts and the €14.5 million figure in the FleishmanHillard-Monsanto contract, that it can be regarded as a clear case of misinformation. This leads to denying EU decision-makers and citizens their right to know about lobbying on an issue of clear public interest (glyphosate), misleading the public about the size and character of Monsanto's massive influencing efforts, and undermining the credibility of the EU Lobby Transparency Register. Corporate Europe Observatory has filed complaints to the Register’s secretariat on both companies.

This strikingly large figure was in fact already made public by the organisation US Right To Know (USRTK), based on a video-taped deposition by Monsanto’s (now Bayer’s) Sam Murphey. He disclosed this information to a US District Court in the context of one of the over 18,400 claims against Monsanto from cancer victims.

Sidley Austin’s report also contains details on what FleishmanHillard was supposed to do for this money. The firm committed to put together a full-fledged lobbying campaign targeting key decision makers, especially at the national level. This involved the ‘stakeholder lists’, which we now know in fact comprised listings of no less than 1,500 individuals across several European countries. Other activities included developing campaign messaging and narratives, as well as research briefs “to deliver credible economic and social impact assessments in each country”. FleishmanHillard was to stay in close contact with Monsanto, giving weekly updates to Monsanto on outcomes, and providing ongoing strategic counsel for, and daily interaction with, Monsanto leads in Europe and the US.

In addition, FleishmanHillard was in charge of Monsanto’s “Let Nothing Go” media campaign. Monsanto’s Sam Murphey in his deposition explained that this campaign involved “carefully monitoring media coverage”, notably across the EU. According to Murphey, FleishmanHillard proactively contacted every reporter who wrote a story that portrayed Monsanto and its products negatively, “to share a statement, to provide some additional context, and to encourage those reporters to contact us in the future”. The work agreement talks about systematically posting “robust responses” to media coverage that was “negative or inaccurate” (emphasis added), not just via traditional media but also on social media.

FleishmanHillard was also expected to set up “grassroots” groups by helping “recruits” to push industry’s pro-glyphosate messages to decision makers. Farmers were a specifically identified target (“Identify & recruit farmers willing to speak out about their need for glyphosate”). For this particular item, Monsanto had also hired lobby firm Red Flag. This company ran Monsanto’s “Freedom to Farm” campaign, organising stands at agricultural shows across Europe which recruited farmers to help lobby for glyphosate. Red Flag was set up by a former partner of lobby firm Hume Brophy, which coordinates the Monsanto-led Glyphosate Task Force. The GTF was in charge of filing glyphosate’s renewal dossier with the EU authorities.

Furthermore, FleishmanHillard was expected to develop arguments that could portray glyphosate as a climate solution, and map and activate “non-traditional” stakeholders, such as “climate advocates in support of sustainable agriculture”.

As reported in Le Monde, the Sidley Austin report reveals that no less than 59 for-hire lobbyists were involved, either employed by FleishmanHillard or by subcontractors at national level. All these activities fall within the remit of the EU Joint Transparency Register, therefore the costs involved should have been declared by both parties in their entries. This would have given the public and decision-makers a more realistic picture of the lobbying firepower of the pesticide industry.

By the end of 2019, officials from four EU countries will take up the task of assessing Monsanto’s next renewal dossier for glyphosate. This time they cannot and should not ignore all of the tricks played by Monsanto to influence this process. While the Monsanto Papers had already demonstrated how the company mobilised its vast resources to undermine the scientific evidence used by regulators, these new files complete the increasingly scandalous picture to show how the company also paid lobby firms huge amounts of money in secret to manipulate the public debate and the opinion of decision-makers.