Power and profit during a pandemic

Why the pharmaceutical industry needs more scrutiny not less

In a pandemic the pharmaceutical industry is hailed as a saviour; yet the industry is using the crisis to lock in its problematic, profit-maximising model. Pushing for public money with no-strings-attached, and stronger monopoly patent rules, the industry’s wish-list could restrict access to COVID-19 drugs and vaccines, prolonging the pandemic in the name of profit. Control over prices and access must not be left in private hands: health is a human right.

Corporate Europe Observatory has uncovered dozens of documents via freedom of information requests – including minutes from weekly calls between pharma and the Commission held during the pandemic – which reveal how the industry is putting profit before an effective pandemic response. The pharmaceutical industry initially used its special access to lobby against joint procurement of treatments in Europe, a tool intended to avoid member states competing for drugs and thus driving up prices. It has also used arguments that pit rich countries against each other (whilst leaving the ones with limited resources behind) to win lucrative advance purchase agreements for potential new vaccines, without the needed public interest conditions in place (this is the kind of joint procurement it does want). But the industry’s fear-and-scarcity based arguments – fuelling vaccine nationalism, pushing stricter intellectual property controls – depend on accepting the flawed monopoly-profit model that it is lobbying to protect, and which actually threatens to prolong the pandemic by leaving many countries unable to afford treatments or vaccines.

In 2019 Corporate Europe Observatory revealed how the pharma industry seeks to preserve a regulatory and intellectual property (IP) regime that enriches its shareholders, but leads to high prices and limits access to medicines. This regime steers medicines research and development (R&D) towards what’s most profitable, while neglecting less financially interesting areas such as poverty-related diseases and pandemic preparedness. As COVID-19 causes hundreds of thousands of deaths around the world, the lobbying of the pharmaceutical industry – which plays a key role in the development of treatments and vaccines – merits close scrutiny. Questions about power and profit are even more important during a global health emergency, as the answers to who controls IP, prices, and access, are written in lives. The pandemic has had a greater impact on lower socioeconomic groups and minorities and the disease (and measures taken to control it) are exacerbating existing inequalities; it is vital that treatments and vaccines are accessible and affordable for all – not just in Europe, but across the globe.

EFPIA lobbied against use of tool for equitable prices for COVID-19 treatments

Many pharma companies have pledged to put global health before profits during the pandemic, but documents released to Corporate Europe Observatory – after long delays – reveal that the European Federation of Pharmaceutical Industries and Associations (EFPIA) lobbied against a tool designed to facilitate equitable access and pricing for pandemic treatments in Europe.

After the 2009 swine flu outbreak the EU set up a joint procurement agreement in response to disparity in member states’ ability to obtain pandemic vaccines and medications. It aims to secure more “equitable access to specific medical countermeasures... together with more balanced prices”. Essentially, the idea is that negotiating together stops pharma companies from ramping up prices by playing member states off against each other.

In July 2020 the European Parliament adopted a resolution calling for “EU joint procurement to be used for the purchase of COVID-19 vaccines and treatments, and for it to be used more systematically to avoid Member States competing against each other and to ensure equal and affordable access to important medicines and medical devices”.

However minutes from a call on 9 March 2020 (a weekly event during the pandemic by Health Commissioner Kyriakides and Internal Market Commissioner Breton with the pharmaceutical and medical devices industries) SidenoteThe weekly calls – which also included the European Medicines Agency – were to discuss possible shortages of medicines and medical devices for the COVID-19 outbreak. reveal that EFPIA said it “would like to continue supplying these new treatments through their usual channels and not by joint procurement”. The ‘usual channels’ would be pricing and reimbursement negotiations at national level, which enable pharma companies to demand higher prices, with no transparency about what is paid by other countries. SidenoteEFPIA wanted “to use the I-SPOC, rather than joint procurement, to discuss with MS on where to allocate production and stocks at EU level”, arguing that “the same results can be achieved” to channel medicines where “the need is most acute”. However, the industry single point of contact (I-SPOC) is a system set up with the European Medicines Agency to help monitor stocks, and avoid shortages, of crucial medicines during the pandemic; since I-SPOC has no bearing on prices paid, its hard to see how it could achieve the same results as joint procurement. Thus the Big Pharma association used its special access to lobby against a mechanism designed to improve equitable access and pricing of pandemic treatments in Europe.

But when it comes to potential COVID-19 vaccines, joint procurement is not so unappealing to the industry (as EFPIA subgroup Vaccines Europe confirms SidenoteVaccines Europe’s June 2020 position paper states: "We support specific advance procurement agreements for extraordinary public health challenges”. VaccinesEurope's members include AstraZeneca, CureVac, GSK, Sanofi Pasteur, and Janssen (Johnson & Johnson’s pharma company), all of which are involved in negotiations with the European Commission for advance purchase agreements for potential COVID-19 vaccines, as of August 2020.) – so long as it is tied up with advance purchase agreements that offer pharma firms incredibly favourable terms.

Competing for vaccines on industry’s terms risks prolonging pandemic

Thanks to industry tactics designed to fan fears of being left behind (see Box 'Support us – or lose out'), combined with Trump’s aggressive ‘America First’ approach to securing potential COVID technologies (for example, buying up the global supply of Gilead’s antiviral drug remdesivir), SidenoteGilead initially applied for ‘orphan drug’ status (normally applied to medicines for rare – and thus unprofitable –diseases as incentives for pharma companies to research and produce them) in the US for remdesivir, after it showed promising signs as a treatment for COVID-19. This was despite the global pandemic making COVID-19 the very opposite of an ‘orphan drug'. Gilead later backtracked, after public outcry over profiteering. For further information, see here and here. first several EU member states, then the European Commission, have embarked on negotiations of advance purchase agreements with pharma companies for millions of doses of vaccines that may or may not prove successful. These lucrative deals are being negotiated in the dark, and use public money to remove financial risk and – very worryingly – liability from pharma companies trying to develop COVID-19 vaccines, without corresponding public interest conditions, for instance related to prices and availability.

Indeed in August 2020 The Financial Times revealed that Vaccines Europe is lobbying the EU for protection against lawsuits and other claims if there are problems with new COVID-19 vaccines. A leaked Vaccines Europe memo shows the corporate lobby group demands a “compensation system” and “an exemption from civil liability”. EU spokespersons confirmed that they’re open to help vaccine companies cover liability costs if something goes wrong with a COVID-19 vaccine, as part of the Advance Purchase Agreements (APAs) currently being negotiated with pharmaceutical companies. With these APAs, governments are paying up front for vaccines that are not yet fully developed, thereby covering potential losses. Yannis Natsis of the European Public Health Alliance warned that an exemption from civil liability would create “a dangerous precedent” and “undermine people’s confidence in vaccines”. Natsis stresses: “Governments need to resist pharma pressure and be transparent”. The Commission has completed a deal with AstraZeneca and is currently negotiating with Johnson & Johnson, CureVac, Moderna, GSK, Sanofi, and others.

Also in August 2020 a Belgian newspaper revealed that former EFPIA Director Richard Bergström is one of seven members on the EU team negotiating these vaccine deals with pharmaceutical corporations. Allowing Bergström – who has been a leading pharma industry lobbyist for years, and is currently involved in two companies (Hölzle Buri & Partner Consulting and PharmaCCX) providing services to Big Pharma – to negotiate these vaccine deals, affecting the health of hundreds of millions of citizens, seems a recipe for conflicts of interest. The names of the six other EU vaccine deal negotiators with Big Pharma are kept secret.

The lack of transparency over these vaccine negotiations, and the contracts agreed – particularly regarding price, IP, liability, and other conditions – urgently needs rectifying: the public interest must override ‘commercial confidentiality’ during a global pandemic, for the sake of patient safety, public trust, and overall confidence in vaccines. But that’s not all: Europe – by giving in to arguments that fuel vaccine nationalism and competition between states – will only make the pandemic last longer, and lead to greater loss of life.

Arguments that take advantage of political fears of missing out, or portray COVID-19 as a zero-sum game (ie if one gains, another loses), only work if we accept the monopoly-dependent model that the industry is so keen to protect. If treatments, vaccines, and manufacturing technologies are not wrapped up in IP that restricts how much can be produced, where, and by whom; and if open science and technology transfer are promoted instead, then this narrative would have far less power to push countries to compete for access. And only the richest countries have a chance of winning this kind of competition, as it depends on spending millions on vaccine candidates that may or may not turn out to be effective and safe, in return for preferential access. This contradicts European Commission President von der Leyen’s commitment, made at the World Health Assmebly in May, of a COVID-19 vaccine as “a universal common good”, that “can be deployed universally, and be available to all”.

What’s more, fair and equitable global access (starting with health workers and vulnerable groups in all countries) is vital to addressing the pandemic, because without it, the disease will continue wherever access has been limited (by inability to pay thanks to unaffordable prices; by pharma monopolies that exacerbate manufacturing limitations; or by rich countries’ vaccine nationalism as they scramble to buy up all potential vaccines doses). As the UN Secretary General says: “No country is safe and healthy until all countries are safe and healthy.” If the disease continues to rage in countries priced out of treatments or vaccines, then even a country with wide vaccine coverage would still be vulnerable (as not everyone will be, or will be able to be, vaccinated; vaccine immunity may not last; and the cost of maintaining border controls, quarantines and travel restrictions for places where COVID-19 is still widespread would be colossal). Vaccine nationalism is not just unethical, it does not make epidemiological or economic sense.

'Support us – or lose out'

In May 2020 Paul Hudson, Chief Executive of French drug giant Sanofi, warned Europe that the US would get its potential COVID-19 vaccine first. Why? Because the US, through its Biomedical Advanced Research and Development Authority (BARDA), had given $30 million to Sanofi towards its research. According to Hudson BARDA did not dictate how many doses the US would receive or their price, instead relying on Sanofi to be “responsible” in making its vaccine affordable. Naturally Hudson is very approving of this lack of R&D funding conditionality, declaring BARDA a “model” for how collaboration with industry should work: public money used to ‘de-risk’ a pharmaceutical company’s investment (ie they get paid whether or not the vaccine proves to be effective and safe), and if it is successful, the company still gets to keep the IP, dictate prices, and reap in the profits.

Released documents reveal that pharma giants like Sanofi were not alone in using this type of 'support us or lose out argument' to lobby for EU support. In March 2020 a venture capital investor approached Commissioner Kyriakides seeking to “jointly coordinate effort on the EU level (funding, requirements, etc.)” with respect to a vaccine candidate by US biotech company Altimmune, which it said required the EU’s help to get it “to the hands of the European population asap”, and to ensure it “does not becomes just an American ‘solution’”. SidenoteThe venture capital investor referred to themselves being affiliated with two firms, Presidio Partners and IPM Group.

Pharma offensive to preserve its monopoly-profit model, but at what cost?

Tied up with arguments that fuel vaccine nationalism is the pharmaceutical industry’s push to further entrench the intellectual property rights that generate such extravagant profits for its shareholders. In December 2019, just before COVID-19 hit Europe, Merck lobbied the Commission for unitary Supplementary Protection Certificates – which would give companies EU-wide monopoly extensions by default, rather than being required to apply in each member state, effectively expanding their geographical scope – and argued that “unmet medical needs (and other challenges related to access to medicines) cannot be fixed by (weakening) IP”. Throughout 2020 EFPIA has ramped up its message that the EU must protect and strengthen IP and incentives – including targeting the Commission’s planned Pharmaceutical Strategy. And despite the growing and widespread critique of this model, many parts of the Commission are still very receptive to it.

Released documents reveal just how closely aligned some Commission directorates are with the pharma industry when it comes to protecting its monopoly privileges. For example, DG Taxud assured EFPIA in December 2019 that it sees protecting IP as “essential and beneficial to businesses and to the health of the EU citizens”. And in January 2020 DG Trade referred to EFPIA as “very appreciative of our last IP report which well reflected their input”, and invited EFPIA to “send information on the pharmaceutical industries’ priorities” for the “negotiations on an African Continental Free Trade Area”. This triggers alarm bells, for good reasons (see Box "Lessons from HIV/AIDS drugs").

Lessons from HIV/AIDS drugs

The history of the pharmaceutical industry's behaviour with regards to their pricing of HIV/AIDS treatments gives little cause for optimism that left to their own devices they can be trusted in a public health crisis.

Antiretrovirals to treat HIV/AIDS became available in wealthy countries in the mid-1990s, but it took a decade of political activism – and millions of lives – before these life-saving treatments were available in poorer countries. The reason? Thanks to patent monopolies, pharma companies were able – and chose – to price them so high (eg around €7,200 per person/year) that many of the worst-hit countries couldn’t afford them. There is a well-documented history of rich countries shaping trade and IP rules in the interests of their pharmaceutical companies, and at the expense of access to medicines in the global south. The struggle for access to HIV/AIDS treatments demonstrates that as Health Gap, an international advocacy organisation puts it: “unless equitable access is set in stone early, countless people will die as a result of a system where charging as much as the richest markets will bear and supplying them preferentially is the order of the day”.

In the context of the pandemic, EFPIA insists that the IP framework “is enabling the rapid R&D response” to COVID-19, and that the only reason a “pool of potential treatments” exists is because of strong innovation policies and effective IP. However critics suggest their monopoly-profit business model is actually part of the reason we weren’t more prepared, or further along in the basic science around coronavirus vaccines. The likelihood of this kind of pandemic was predicted, but the pharmaceutical industry had little interest in preparing for it: uncertain profits from a future disease outbreak cannot compete with guaranteed profits from blockbuster medicines, orphan drugs, me-too drugs, and ‘evergreening’ patent practices. And it’s these strategies, which rely on the IP and incentives regime, that maximise profits for shareholders (and lets not forget, many pharma companies spend more on share buybacks and dividends than on R&D). This is why, after initial research in the early 2000s into other coronavirus outbreaks – SARS and MERS – companies (and governments) lost interest as cases receded and a profitable market looked unlikely. Hence no vaccine for either of those coronaviruses exists to this day. SidenoteIt is notable, however, that a current frontrunner vaccine candidate comes from the part-publicly funded Oxford University’s Jenner Institute, which did carry on researching a vaccine for MERS, and built off that to produce its COVID-19 candidate. Oxford University then signed an exclusive deal with AstraZeneca that gave the Big Pharma company sole rights, with no guarantee of low prices (reportedly at the encouragement of the Gates Foundation), in a U-turn from its earlier stance that it would donate the rights to its vaccine to any drugmaker.

iIt is notable, however, that a current frontrunner vaccine candidate comes from the part-publicly funded Oxford University’s Jenner Institute, which did carry on researching a vaccine for MERS, and built off that to produce its COVID-19 candidate. Oxford University then signed an exclusive deal with AstraZeneca that gave the Big Pharma company sole rights, with no guarantee of low prices (reportedly at the encouragement of the Gates Foundation), in a U-turn from its earlier stance that it would donate the rights to its vaccine to any drugmaker.

The EU-EFPIA public private partnership, the Innovative Medicines Initiative (IMI), is another example of this profit-before-pandemic-preparedness dynamic, despite the fact that IMI’s mission is to address neglected areas of medical research. In May 2020 Corporate Europe Observatory revealed how EFPIA’s dominance in IMI has de-prioritised the public interest, including the pre-COVID rejection of an EU proposal for IMI to work on fast-tracking vaccines for pathogens like coronavirus to allow them to be developed before an outbreak, in favour of more profitable disease areas that have no shortage of R&D funding.

IP and access to medicines expert Professor Brook Baker, a proponent of sharing COVID-19 technology and IP, sums up why intellecual property rights are actually a major obstacle to tackling the disease: The most irresponsible barrier in the middle of a global pandemic threatening millions of lives are government-granted monopolies to Big Pharma and Big Medical Device/Testing companies. These intellectual property monopolies not only impede open science needed to accelerate medical discoveries of new tests, therapies, vaccines, and medical devices but they also limit production to single suppliers who can in no sense meet urgent global demand and who might price gouge and prioritize supply to rich and powerful countries.

Yet the idea of pooling technology and IP to facilitate scientific discovery and increase manufacturing capabilities – even voluntarily, through the WHO’s COVID-19 Technology Access Pool (C-TAP) – has led to angry objections from Big Pharma. Pfizer described it as “dangerous” and “nonsense”, whilst AstraZeneca said companies should instead “volunteer to provide their products at no profit” during pandemics. Essentially Big Pharma companies’ pandemic narrative is that they want to keep all the IP and all the public money for R&D, and in return, the world should just trust them to be good (see Box 2 'Lessons from HIV/AIDS drugs' for why that is a terrible idea).

As another example of this, GSK wrote to Commissioner Kyriakides in April 2020 about its vaccine collaboration with Sanofi, saying that both companies “are committed to making any vaccine that is developed through the collaboration affordable to the public and through mechanisms that offer fair access for people in all countries”. The message is, 'you can rely on us to do right thing, so there’s no need for...' pricing and access conditions on public funding, compulsory licensing, pooling IP and technology, or any other public interest measures. However, not only are these seemingly altruistic promises actually about keeping the power to control access in private, for-profit hands, they’re also vague, unaccountable, and unverifiable, thanks to a lack of transparency over pharma companies' costs and profits. Pretty promises aside, as the AIDS crisis showed, the pharma industry has a well-documented history of placing profits above lives.

In a similar vein, EFPIA has come out with its own proposals on how to deal with access problems to high price medicines. In July 2020 EFPIA launched its ‘Novel Pricing and Payment Models’ (though it lobbied DG Sante about them back in January), responding to national payers’ inability to afford their costly new drugs. One model is ‘Over-time payments’, which “allow for payers to make payments to manufacturers over fixed periods… to mitigate the high up-front cost” of new therapies. Effectively, this puts countries in debt to pharma companies, as if purchasing life-saving treatments was like buying an expensive car on credit.

Such models ask governments to accept colossal price tags, whilst ignoring the vast public and charitable investment in R&D of such therapies, and companies’ lack of transparency on their R&D costs. But EFPIA’s justification is that its models are “value-based”, reflecting not only therapeutic value to the patient but “economic value, including indirect benefits and societal value”. However, as Global Justice Now has pointed out, this could justify almost any price: “imagine how much seat-belts, smoke alarms, or even soap would cost, when you factor their value in terms of costs to the health service avoided, and economically productive members of the workforce saved”. SidenoteThe author of this article also contributed to the Global Justice Now report that this quote is taken from.

Imagine if COVID-19 treatments or vaccines were priced by their value to economy and society, in a pandemic that has caused widespread lockdowns and economic recession; they would be unthinkably expensive, and unaffordable to vast swathes of the global population. Although pharma companies have shied away from using this value-based pricing argument with respect to COVID-19, it is nonetheless a warning signal about the high-price, low-access model they’re lobbying to defend. And already, US company Moderna is refusing to price its potential Covid-19 vaccine at-cost – despite receiving almost $1bn in public money to develop it, it plans a price tag that will make it inaccessible for lower income countries. Despite their PR, it is not enough to leave pricing, access and technology transfer decisions to the goodwill of pharma companies.

Pharma industry's lobby firepower

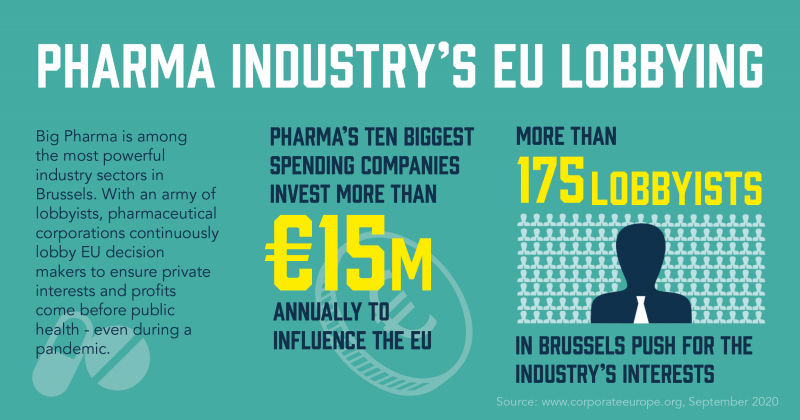

As part of its influencing efforts, the pharmaceutical industry spends massive amounts on lobbying in Brussels. The top ten biggest-spending pharmaceutical companies currently report spending between €14.75 and €16.5 million per year on lobbying in Brussels. SidenoteLobby spending according to the companies themselves, reported as part of their entries in the EU’s Transparency Register (as of 14/9 2020). The top ten consists of Bayer, Novartis, GlaxoSmithkline, F. Hoffmann-La Roche, Sanofi, Johnson & Johnson, Amgen Inc, Pfizer, Gilead Sciences, and Merck (MSD). They also come together via pharma lobby groups, the top five of which also report spending another €5.7 and €6 million annually, according to the EU’s lobby transparency register. SidenoteThe top five are EFPIA, Medicines for Europe, Vaccines Europe, EUCOPE, and AESGP. Data from the EU’s Transparency Register (as of 14/9 2020). Combined, the industry employs around 175 lobbyists working to influence EU decision-making. There are 58 pharma lobbyists with permanent access passes to the European Parliament. Pharma companies and their lobby groups have had almost 200 meetings with the top of the European Commission since 2014, 85 of which have taken place since the start of the Covid-19 pandemic. SidenoteData from the EU Transparency Register (as of 14/9 2020). Meetings since 1 March 2020. The full picture of pharma lobby spending also includes large amounts spent via lobby consultancies, think tanks, and patient organisations. An in-depth investigation by Corporate Europe Observatory in 2015 concluded that the sector’s annual total lobby spending is likely to be over €40 million.

Conclusion

The COVID-19 pandemic is a global crisis, and health is universal human right. Successful, safe, and effective treatments and vaccines for COVID-19 should be a public good, available and affordable to all. We must not be wooed by pharma companies’ promises to do the right thing: as their continued lobbying efforts at EU-level show, private interests and profits come before public health, even during a pandemic.

There are also signs that the industry wants the regulatory flexibilities put in place during the crisis, and its increased political access, to become the new normal. EFPIA is calling for the Commission to set up a High-Level Forum on Better Access to Health Innovation. EFPIA says the forum would enable an “analysis of the root causes of unequal patient access and supply of medicines” and – in a clear signal of whose interests it would promote – that “[s]uch an analysis will show that an effective, targeted response to the access and availability challenges does not lie in a reduction of incentives for innovation”.

Critiquing the IP and incentives model that primarily serves shareholders and executives is in no way intended to devalue the efforts of all those working to develop treatments, technologies and vaccines for COVID-19, in the public and private sectors. However, the pharma industry’s cries that innovation will falter if we dare tweak their lucrative IP and incentives regime don’t stand up to scrutiny. Many alternative models exist; models, moreover, that are “open and collaborative and built around principles of equitable R&D that meet human needs and gathering threats”.

Civil society groups around the world are campaigning for a pandemic response based on international cooperation and solidarity, rather than nationalism and monopoly-profits, for example:

-

People’s Health Movement, for example, is working to challenge structural barriers to Equitable Access to Essential Health Technologies in the context of COVID 19, from the dominance of Big Pharma to trade-related IP rules.

-

More than 65,000 Europeans have signed a petition requesting that COVID-19 medicines and vaccines are affordable, an initiative by WeMove and the European Alliance for Responsible R&D and Affordable Medicines.

-

The ‘Right to Cure' campaign last month launched a European Citizens' Initiative calling upon the EU to "make anti-pandemic vaccines and treatments a global public good, freely accessible to everyone". The campaign now has 12 months to collect one million signatures in EU member states, encouraging the European Commission to propose legislation to implement this important demand.

This pandemic affects everyone, everywhere – that’s a lot of people power! And its up to us to use it, to demand that public investments come with public interest conditions, on pricing, access, and open science; to insist that IP monopolies have no place during a global pandemic, and that COVID-19 research and know-how is pooled; to call on leaders to make use of tools like compulsory licensing when faced with access-limiting monopolies and high prices; and, ultimately, to ensure that access to treatments and vaccines is based on equity, fairness, and need.

As a follow-up to this investigation, Corporate Europe Observatory has filed two Freedom of Information requests to the European Commission to throw light on the excessively secretive negotiations about Advance Purchase Agreements for Covid19 vaccines. We have requested access to the vaccine deal contracts and asked to receive all correspondence and minutes from meetings between the EU's vaccine deal negotiators and the pharmaceutical companies. The European Commission's deadline for responding to the FOI requests is 6 October 2020.

Written by Rachel Tansey and edited by Katharine Ainger. Authorial contributions from Olivier Hoedeman and Katharine Ainger. With thanks to Viviana Galli (European Alliance for Responsible R&D and Affordable Medicines) and Leigh Haynes (Peoples Health Movement).

Cover image: Matt Allworth via Flickr (CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)