Derailing EU rules on new GMOs

CRISPR-Files expose lobbying tactics to deregulate new GMOs

With the European Green Deal and the Farm to Fork Strategy, the Von der Leyen Commission has committed to a fundamental shift away from industrial agriculture as we know it today. With a 50 per cent pesticide reduction target, and a 25 per cent organic agriculture target by 2030, business as usual is no longer an option. This creates an existential crisis for those corporations that are dominant both in the pesticide and in the commercial seed market, notably Bayer, BASF, Corteva (DowDupont) and Syngenta (ChemChina).

These corporations are set to lose a large share of their profits from selling pesticides, and are therefore looking for a new business model: increase profits from the seed business. This applies all the more to German chemical giant Bayer, which is in deep financial trouble since buying Monsanto, because of ongoing and costly glyphosate litigation in the US. To have new GMO seeds without regulatory oversight, but still patented, would surely serve that aim.

Executive summary

The biotech industry is waging an ongoing battle to get its new generation of genetic modification techniques excluded from European GMO regulations. This would mean that plants, animals and micro-organisms, made using ‘genome editing’ techniques like CRISPR-Cas, would not be subject to safety checks, monitoring or consumer labelling. Corporate Europe Observatory has uncovered various new tactics used by the biotech industry to prepare the ground for such deregulation. Officials from national ministries were hand-picked for joint strategy meetings with lobbyists; a think-tank set up a new Taskforce with a large grant from the Gates Foundation to pave the way to GM deregulation via "climate narratives"; and a lobby platform built around a sign-on letter overstating its backing by research institutes. The European Commission is due to publish a study by the end of April about the new techniques which will provide a basis for further discussion among Member States. Civil society and farming groups call on the EU to prioritise environmental and health concerns, and keep GM safety checks in place.

About the CRISPR-files: Corporate Europe Observatory has shared large sets of documents obtained through Freedom of Information requests to the European Commission and to the Belgian and Dutch governments, with a number of investigative journalists. All documents are now available online.

Media coverage: Spiegel (DE), EUObserver, Reporterre part 1 (FR), Reporterre part 2, La Libre Belgique, apache.be (BE), El Diario (ES), Il Domani (IT), Público (PT), Reporters United (EL).

Follow up coverage appeared in De Standaard (BE), Libération (FR), Le Courrier du Soir (FR), Counterpunch (US)

Introduction

For many years the biotech industry has lobbied the European Commission not to regulate products made using new GMO techniques, including ‘genome editing’ techniques such as CRISPR-Cas. SidenoteGene editing techniques such as CRISPR guide molecular scissors (known as site-directed nucleases, SDNs) to the location on the genome where the DNA change is intended to take place. Depending on the technique, these guided molecular scissors are in the form of synthetic proteins, or synthetic RNA-protein combinations. The molecular scissors cut the DNA, which then undergoes repair using the cell’s own repair mechanism. Often, a synthetic DNA template is used to direct the repair in such a way that a particular change in the DNA is achieved. This gives rise to different types of gene editing. Source: Dr. Janet Cotter, Logos Environmental, U.K. and Dana Perls, Friends of the Earth, U.S. Gene-edited organisms in agriculture: risks and unexpected consequences. 2018. However on 25 July 2018 the European Court of Justice ruled that such genome editing procedures are GM techniques and its products must be regulated as such. Since then, industry and researchers have been pushing hard to change the EU GMO law (2001/18) in order to get genome editing deregulated (ie with no risk assessment, monitoring, or labelling).

But there are two huge hurdles to overcome. First, each decision on GMOs in the EU is highly contested, therefore it will be hard to find enough support to overhaul the EU GMO regulations. Second, and connected to the first, public support also has to be won. Therefore, wild promises are being made about the alleged benefits of crops and animals which are made using genome editing techniques, to convince the public of their value. Similar promises were also made for GMOs in the past, but never proved true.

The lobby tactics described in this briefing appear to firstly focus on legal strategy, and secondly, to develop a positive PR narrative of, for example, climate-friendly ‘flagship products’, in order to gain public acceptance for new GMOs. They are also a good example of the typical echo-chamber that comes with big industry lobby campaigns, whereby decision makers are exposed to multiple voices all bringing the same message. The lobby initiatives described in this briefing appear to be driven by public research organisations, however they have close ties to corporate interests.

Through Freedom of Information requests to the European Commission and the Dutch and Belgian governments, Corporate Europe Observatory (CEO) has uncovered new information about recent lobby tactics employed to undermine and change existing EU GMO regulations in order to let new GM plants and animals – obtained via genome editing techniques – go unregulated unto the EU’s internal market. This would mean: no biosafety, food safety, or environmental assessments; no monitoring, and no freedom of choice for consumers (due to a lack of product labelling).

It is now a decisive time, as the European Commission' health division DG SANTE will publish a study by 30 April 2021, which may contain 'policy options' to change the EU’s GMO laws. The study was requested by the Council under the Finnish Presidency, as Member States wanted answers to practical questions of the implementation from the ruling. But as a Friends of the Earth investigation argued, “the set-up of the study has now given rise to strong concerns that the process has been captured by industry”. This is because the basis of the study is a highly biased ‘targeted stakeholder consultation’ which was dominated by industry.

1. Setting up meetings with hand-picked officials, winning hearts and minds of public: EPSO’s strategy to deregulate new GM

Freedom of Information requests to the Belgian and Dutch authorities reveal that the Brussels-based ‘European Plant Science Organisation’ (EPSO) has been holding a series of lobby meetings with hand-picked national officials from selected countries and selected ministries. The objective of these meetings is to get genome editing techniques deregulated. Discussions focused on the one hand on what would be least difficult legal route to obtain deregulation; and on the other hand to find ‘flagship projects’ of genome edited products that could win hearts and minds of the public. Three meetings have been held so far (September 2019, January 2020, November 2020) and a fourth is planned for May 2021.

The invitation to the first meeting read, “The meeting will be an open-minded, informal discussion under Chatham House Rules between plant scientists (1 / country) and policy makers (1-2 / country)”. Participants were invited “from countries which already indicated to support an innovative approach for agriculture and plant breeding in Europe” (by ‘innovative’ they mean friendly to new GM). The objective is for EPSO “to collaborate with policy makers to develop an appropriate future-ready regulation” for new GMO techniques.

However, few if any of those countries actually have an official position on the topic. In some countries, as in France and Germany, the ministries of Agriculture and Environment respectively have opposing views. And it is unclear whether the Environment ministries in these countries have been made aware of the existence of these meetings.

What is EPSO?

EPSO is a Brussels-based organization focused on influencing EU research policy and funding priorities in plant science on behalf of a number of institutes. EPSO also coordinates and is involved in (public-private) research activities among its members, including on genome editing products (such as here). EPSO and biotech industry lobby group EuropaBio jointly set up the European Technology Platform (ETP) ‘Plants for the Future’. ETPs are industry-driven platforms set up to help shape the EU research agenda in different areas. SidenoteThese platforms have been criticized in the past by Corporate Europe Observatory and other organisations as they enable a narrow set of large corporations to shape the EU research agenda in their favour, and to then profit from the funding available.

In 2019 the ETP Plants for the Future platform co-signed an otherwise all-industry lobby letter to member states protesting against the 2018 decision by the European Court of Justice, ruling that genome editing techniques are genetic modification, and have to be regulated as such.

EPSO itself also has many observers, which “have the opportunity to give their input” when the organisation “produces a statement or a recommendation”. These observers are nearly all big companies and industry lobby groups including EuropaBio, BASF, Limagrain, Bayer, Syngenta, etc.

EPSO has eight working groups. The working group on Agricultural Technologies is the one organizing the meetings on the deregulation of genome editing. It is likely that several members of this working group participated in the EPSO meetings.

Who participated?

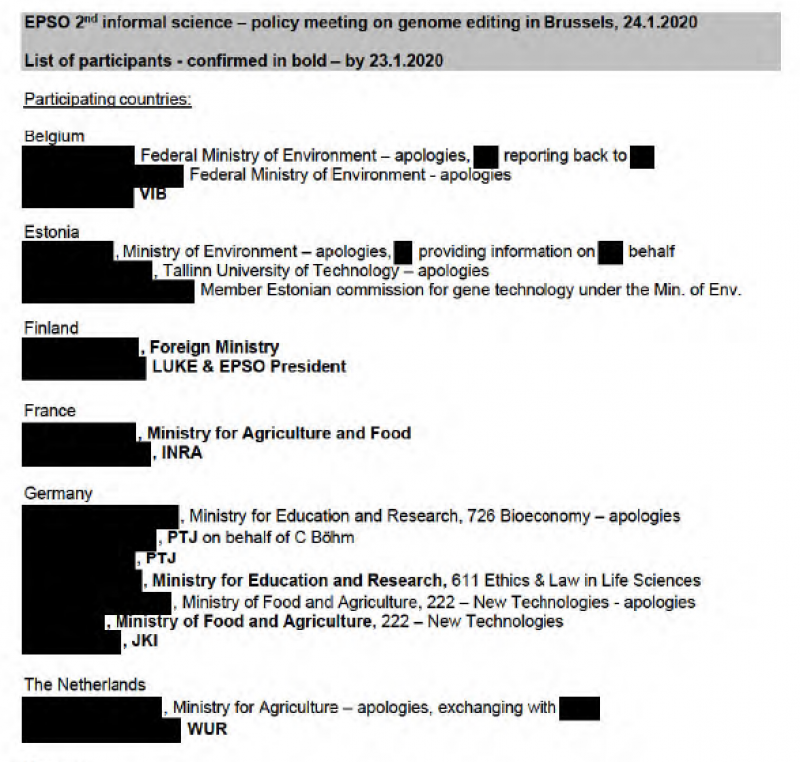

The documents contain participants lists, however the names listed are censored.

The kick-off meeting held in September 2019 in Brussels was attended by officials from seven EU countries: Belgium, Finland, France, Germany, the Netherlands, Spain and Sweden. Three countries were on the list, but did not attend. SidenoteSee doc. EPSO_1, p.82

As for the researchers, from the documents we can deduct that René Custers attended for the Flanders Institute for Biotechnology (VIB, Belgium), Ernst van den Ende for Wageningen University (Netherlands), and Ralf Wilhelm for the German Julius Kuehn Institute (JKI). Others are likely to be members of the EPSO Agricultural Technologies working group.

At the second meeting in January 2021 in Brussels, attendance from member state ministries was lower, with many cancellations and only officials from Finland, France, and Germany attending. For Germany, no less than four officials from two ministries attended. The list of countries had expanded to twelve, this time including Denmark and Lithuania. SidenoteSee doc. EPSO_2, p.6 and p.170.

The meetings: legal strategies and flagship projects

The discussions at the meetings evolved around two main topics:

1) The question of which legal strategy would be best to get the GMO directive changed with the least political resistance.

2) The question of which genome editing ‘flagship projects’ would be able to win the hearts and minds of the European public and policy-makers, after decades of GM crops failing to do so.

At the first meeting, officials provided updates on internal discussions in their respective countries. In the meeting report, the option that many genome edited organisms would not undergo any safety checks, instead only needing a simple notification procedure, was discussed. This would be the case for genome editing products that – according to the lobbyists - could also have been achieved by classical breeding or even in nature.

In practice, GM developers do not demonstrate that these mutations actually are achieved in exactly the same way by other techniques or in nature. However, these techniques do cause unintended effects and bring other specific concerns, as explained by the German organisation Testbiotech.

Other considerations on the table were to “strengthen European competitiveness” and “offer a free choice to developing countries to use the technology without restrictions when exporting their products to Europe.”

One example of a potential flagship project – to reach the hearts and minds of the public and policy-makers – was to “diversify the taste” of “crops that has been unified” [sic], ie to promote new GM techniques as a way to bring back a diversity of flavours to food crops. This is rather ironic given the fact that monocultural, industrial agriculture has caused enormous genetic erosion, significantly reducing genetic diversity in cropsasa consequence of choices made by the seed and food industries. Many crop varieties, including fruit and vegetables, have disappeared as a result.

To convince the officials that there is overwhelming support for the deregulation agenda, EPSO’s own PowerPoint presentation SidenoteSee EPSO_1 p.59 highlighted several statements: an open letter by several industry lobby groups, the EPSO statement (suggesting it was supported by “over 200 research institutions”, ie the EPSO members), and the VIB-led statement by researchers (which also made the claim that it was supported by “127 research institutes”). (See also section 3 on EU-SAGE below).

Officials present at the meeting were encouraged to invite colleagues from other ministries in their own country, or from other EU countries, to future meetings. Officials were also invited to join a “mailing list to receive… updates regarding genome editing legislation and efforts to improve the legislation.” In December 2019 a first news roundup was sent to this mailing list. The idea was launched to also invite Commission officials and MEPs to future meetings.

The officials were also asked to share in advance a draft decision by the Council under the Finnish Presidency, that called on the Commission to undertake a study (currently being finalized by DG SANTE), “clearly stating the level of confidentiality we need to apply”. This means that information might have been shared by officials with lobbyists, information that was not available to others.

The EPSO PowerPoint SidenoteSee doc. EPSO_1, p.78 also mentioned that “EPSO could link the next meeting(s) to the Finnish and German Presidencies subject to visibility you wish”.

The second meeting was held in January 2020. The report of this meeting SidenoteSee doc. EPSO_2, p.80 contains detailed discussions on the preferred legal options and routes to deregulation. Here several options are laid out. For instance the Belgian VIB expressed preference for a ‘quick fix’ by expanding an Annex to the EU GMO Directive (2001/18/EC), that excludes certain techniques.

A comment was added that “we need to be careful how we rewrite recitals, so as to overcome Recital 17”. Recital 17 of the 2001/18 EU GMO directive excludes certain techniques of genetic modification “which have conventionally been used in a number of applications and have a long safety record”.The directive clarifies that this only applies to a few specific techniques that were in use long before 2001. As the ECJ also confirmed, new GM techniques like CRISPR in any case do not have a long safety record. This is why Recital 17 would have to be “overcome”.

The January 2020 report’s conclusions show that a quick fix-approach to deregulate genome editing products is seen as necessary – “to be competitive globally”– but not enough. At least some of the participants aim for “a long-term paradigm shift” towards legislation that is product-based. This would mean that GMOs would only be assessed looking at their new trait, not taking into account the process (ie the technique) by which they were created. SidenoteA summary of reasons why all new GMOs ought to be subject to safety checks, published by the organization Testbiotech can be found here.

Officials were told that if GM regulations were lifted, “other regulations exist that will still ensure safety”. However, these other regulations (such as plant variety registration) do not assess food safety and environmental aspects as the GM risk assessment does, according to this analysis commissioned by the German Federal Agency for Nature Conservation.

Regarding the European Commission study, expected by the end of April 2021, participants agreed on its high importance and the “need to take action to coordinate our inputs.”

The participants were also informed about a consumer survey on new GM from Norway that seemed to conclude that consumers would support applications that would benefit society. They were not told that the Norwegian Centre for Biosafety GenØk criticised the survey for overstating certainty around benefits while ignoring the risks.

However, the question is whether the patent regime will allow the small breeding companies that still exist to become real players in the seed market. Companies like Corteva have already become major license-holders of some of the key CRISPR-patents. Indeed, patents are a bigger hurdle than regulation, as Dr Michael Antoniou of King’s College argued at a Brussels panel debate.

In the discussion one participant argued that “policy makers need to know which problems we can help to solve with these new technologies”, such as “reducing pesticide use as stated in the European Green Deal”. The flagship projects, it was argued,should be focused on challenges, such as reducing pesticide use or improving drought tolerance, and deliver concrete results for the European market soon.

However, no concrete examples were mentioned. Despite the claims, there is a clear lack of examples of new GM crops that would genuinely and meaningfully meet the challenges mentioned. In fact, promising results are being achieved in conventional breeding.

In the third meeting held in November 2020, an invited MEP claimed that the ECJ ruling made “new breeding techniques almost impossible”. The document does not disclose who this MEP was. He continued by saying that “A historic opportunity is being missed. Climate change and the gradual banning of plant protection products make the use of GE a key contributor to green solutions”.

Officials present at this third meeting confirmed that there are strongly diverging opinions between Environment and Agriculture ministries in various member states. This is known to be the case in France and Germany.

The meeting’s conclusions suggest engaging with the European Commission to have GMOs less regulated in order to employ them against climate change; and to develop stronger narratives to illustrate how genome editing “can contribute benefits to society”.

In another document shared with the officials at this meeting, EPSO argued againthat “new concepts for deregulation, based on public-private risk and benefit sharing, need to be developed to enable SMEs bringing such products [genome editing] to the market.” But would such concepts not benefit big seed multinationals even more?

According to the report, a next meeting is planned for May 2021, and will focus on discussing the expected study from the European Commission.

Déjà-vu?

These EPSO meetings represent a disturbingly close level of collaboration between decision makers and lobbyists. Interestingly, the VIB hosts a lobby group in its offices that organised similar meetings targeting the UN biosafety negotiations. This group, called Public Research and Regulation Initiative (PRRI), claims to represent public researchers, however its positions are fully aligned with those of industry. PRRI first established itself using grants from Monsanto and Croplife.

A 2018 Corporate Europe Observatory report describes how PRRI convened lobby meetings between lobbyists and officials of ‘like-minded’ countries, ahead of important UN talks on biosafety and biodiversity. Its founder Piet van der Meer, a former Dutch GMO official, also runs a consultancy and is guest professor at the Vrije Universiteit Brussel (VUB). He now appears frequently at EU events as a speaker in favour of deregulation of new GMOs.

2. Gates Foundation funds think-tank Reimagine Europa to push for deregulation of genome editing

Think-tank Re-Imagine Europa (RIE) has a stated mission “to reinforce Europe’s role as a global economic power in the 21st Century able to safeguard a prosperous future of peace, freedom and social justice for all its citizens”. The think-tank was co-founded by former French head of state Valéry Giscard d’Estaing who recently passed away.

Re-Imagine Europa has a specific methodology: setting up a taskforce for each of three “strategic challenges” (‘Democracy’, ‘Economy’, and ‘Planet’) that involve “an expert committee of roughly a hundred experts from academia, think tanks, industry, NGOs, CSOs, and other stakeholders”.

The topics for the taskforces are selected by the Advisory Board. Re-Imagine Europa explains that in 2018 some of its Advisory Board members requested the launch of a “Taskforce on Innovation and Climate”. These included MEP Paolo De Castro and the former Research, Science and Innovation Commissioner Carlos Moedas. Both of them have made public statements in the past favouring the deregulation of new GM techniques.

For this taskforce alone, the think-tank was awarded a whopping $1.5 million grant from the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation (BMGF). The goal of the taskforce is described on the Gates Foundation website in clear terms: “to engage with a broad set of European stakeholders on genome editing in the 21st century”.

Th BMGF grant, dated July 2020, does not yet feature in the think-tank’s entry in the EU Lobbying Transparency Register. Here, Re-imagine Europa currently has a total declared budget of just under €50,000. Its entry states that, as “Re-Imagine Europa wants to work for the interest of the European citizens”, they would aim for a budget where “1/3 of funds come from public/foundations, 1/3 from private and 1/3 crowdsourced”.

Its website states that “Re-Imagine Europa is funded by leading foundations including: La Caixa Foundation, Fondazione Cariplo, Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation as well as project-based funding from the European Commission”.

The ‘Sustainable Agriculture and Innovation’ Taskforce has its own Steering Committee, with an extremely biased composition. It includes many very outspoken deregulation proponents, such as Paolo de Castro MEP, Garlich von Essen (Euroseeds, the seed lobby), Pekka Pessonen (big farm lobby Copa-Cogeca), Dirk Inzé (VIB and EU-SAGE), and Pere Puigdomenech (Barcelona Center for Research in Agricultural Economics, and board member of All European Academies (ALLEA)).

ALLEA and EU-SAGE (a lobby platform set up by the Flanders Institute for Biotechnology, VIB; see section 3 below) are both sub-awardees to the Re-Imagine Europa project on genome editing. It is not clear how much they were awarded, nor for what work.

In November 2020 the new ‘Taskforce on Sustainable Agriculture & Innovation’ was launched. In an overview document posted on the think-tank’s website, Re-Imagine Europa explains that the taskforce was set up in light of the European Green Deal and the Farm to Fork Strategy, and the expected changes they will bring for the agricultural sector. The taskforce would “create a forum for real dialogue between different viewpoints on these issues”.

However, the taskforce only has one focus, and that is the deregulation of genome edited crops and animals. Just like the EPSO lobby meetings with officials, the taskforce focuses on two questions: what is the most opportune legal strategy for deregulation, and how can genome editing techniques be framed as a solution to climate change.

The list of members of the taskforce’s expert committee was published online by Re-Imagine Europa on Friday 26 March 2021 following media requests. Among the 55 members currently on the list, the large majority represents the biotech industry, GM researchers, pro-biotech lawyers and mainstream farming interests. There are very few people on the list with extensive experience in sustainable farming practices. (See Box). This will certainly not allow a genuine “dialogue between different viewpoints”.

The expert committee only has one representative from an organic farming organisation. The fact that the European Green Deal wants to boost organic production, plus the fact that this sector rejects GMOs, clearly stands in the way of creating a green image for CRISPR and the like. Therefore, the taskforce concludes that the boundaries between “so-called industrial agriculture and organic production” would have to be “redefined”.

Which experts to shape vision on ‘sustainable agriculture and innovation’?

BASF and Bayer both are represented by two people on the expert committee. In addition, Petra Jorasch is there on behalf of seed lobby Euroseeds, and Claire Skentelbery on behalf of biotech lobby EuropaBio. Intellectual Property Lawyer Philippe de Jong of law firm ALTIUS is, according to the firm’s website, himself a member of Euroseeds. Dirk Hudig (chairman of lobby firm FIPRA) represents the European Regulation and Innovation Forum, formerly called the European Risk Forum (ERF). This lobby group is known for its attacks on EU environmental protection levels. Its members include Bayer, BASF, Dow Europe, Syngenta, FoodDrinkEurope and chemical lobby group CEFIC. FoodDrinkEurope is represented by Mella Frewen, a former Monsanto lobbyist.

The French biotech lobby group AFBV has two people on the expert committee. Philippe Dumont, one of them, is on the board of Calyxt, a US company commercialising a soybean made by a genome editing technique (TALEN). AFBV’s founding members include representatives of French seed company Limagrain, of Aventis CropScience and French big farm lobby FNSEA.

The VIB and EU-SAGE are represented by two people, René Custers and Oana Dima, and a third is on the taskforce’s steering committee (Dirk Inzé). Piet van der Meer is consultant and the founder of biotech lobby group PRRI. SidenoteSee also section 1

Gijs Kleter is a former EFSA GMO Panel member, who previously worked with the industry-backed International Life Sciences Institute (ILSI) on risk assessment. He has published various papers on the regulation of GMOs, among others with Peter Kearns of the OECD, who is on the taskforce’s steering committee.

Marcel Kuntz is a staunch glyphosate-defender and regularly posts on the pro-biotech site Genetic Literacy Project, as well as a member of AgBioChatter, which the NGO US Right To Know reported as a “private email listserver used by the agrichemical industry and its allies to coordinate messaging and lobbying activities”.

Marco Perduca represents Science and Democracy, a small group of individuals “defending the human right to science”. SidenoteSee also section 3. EU-SAGE

Mark Lynas is employed by the Gates-funded Cornell Alliance for Science, a platform to promote GMOs. He is frequently criticised for flawed and misleading argumentations, including that agro-ecology “risks harming the poor in Africa”.

Kai Purnhagen (University of Bayreuth) and agricultural economist Justus Wesseler (Wageningen University), both known pro-deregulation defenders, recently proposed the absurd argument that the contribution of biotechnology to the creation of a vaccine for Covid-19 would somehow be an argument to deregulate GMOs.

Peter Chase is from the US think-tank the German Marshall Fund (GMF), sponsored by numerous corporations including Bayer. The US government is represented as well, by Bruce Zanin of the US Mission to the EU.

Another person is from the European Policy Center (EPC) whose members include BASF, Dow, FIPRA and Philip Morris International.

Two MEPs are part of the expert committee, including Norbert Lins (EPP), the chair of the European Parliament’s Agriculture Committee. He played a big role in the Parliament’s actions to water down a greening of the EU’s Common Agricultural Policy (CAP), thereby undermining the objectives of the European Green Deal.

Previous lobby activities

The Gates-funded taskforce is seen by Re-Imagine Europa as a follow-up to two closed 'Science in Society salons' about the same topic that it organized with the European Commission’s Scientific Advice Mechanism (SAM). The meeting report of one of these Salons showed that participation was very biased; there was only one environmental NGO present. At that time Reimagine Europa was supported by a small grant from Bayer.

Erika Widegren (RIE) also chaired a Symposium organized by Flemish Academy of Science and ALLEA in 2019, dealing with the regulation of genome editing. There is quite an overlap between the members of the taskforce’s expert committee, the speakers in the Symposium, and the participants to the Science in Society Salon.

It is not the first time that the Gates Foundation has funded a lobby operation of this kind. In 2017 the Gene Drive Files revealed that the Foundation paid a lobby firm a similar amount ($1.6 million) to run a covert ‘advocacy coalition’, to skew the only UN expert process addressing gene drives, a highly controversial application of genome editing techniques.

The Gates Foundation spent billions of dollars on its programme Alliance for a Green Revolution in Africa (AGRA), but received strong critique over locking African farmers into a system that is designed to benefit corporations more than them. The Gates Foundation also spent up to $22 million to fund the Cornell Alliance for Science, a group with a stated mission to promote GMOs. The organization US Right to Know published an overview of the Alliance’s often deceptive tactics.

The report ‘Gates to a Global Empire’, co-written by NGOs and authors around the world, describes a pattern when the Gates Foundation gets involved: after raising an issue to the global agenda, the Foundation will then propose some technological solution. They will fund “start-up companies, research institutions and research departments of private companies” to develop the technology. Then, other Gates’ initiatives begin “lobbying the regulation process for ease of implementation of this technology”. The commercialization of the product can then be taken over by private companies. All of this is veiled behind “the rhetoric of a humanitarian, development cause, such as increasing income for small farmers, or providing solutions to climate change”.

The EU plays an important role in the international debate on the regulation of GM technologies, such as at the UN Cartagena Protocol negotiations on biosafety. This may explain why the Gates Foundation funds an EU level lobby operation. An overhaul of the EU GMO rules has the potential to impact the way genome editing is regulated in other parts of the world as well.

3. EU-SAGE: a platform overstating its scientific backers

A few months after the ruling of the European Court, a group of researchers led by the Flanders Institute for Biotechnology (VIB) sent a letter to then-President of the European Commission, Jean-Claude Juncker, expressing concern about the consequences of the ruling. They urged the outgoing Commission to prepare policy proposals that would exclude the new GMOs from the existing GMO legislation, and to ensure that member states lent their support. SidenotePart 4, doc 134

In January 2020 this lobby initiative was renamed as ‘EU-SAGE’ network and registered as such in the EU lobbying transparency register. The three people listed as running the network are all VIB employees: Scientific Director Dirk Inzé, lobbyist René Custers, and post-doc researcher Oana Dima. One of the reasons to set up EU-SAGE may have been that this opened up the opportunity to participate as an EU-level stakeholder in the consultation for the European Commission study.

In that same month, EU-SAGE called on Von der Leyen and other Commissioners to “safeguard gene editing for sustainable agriculture”. They again claimed to “represent 129 plant science institutes and societies”. They state that “strong political signals” are necessary to break the deadlock and “to prevent irreversible damage to our European economy and to a transition to a green economy”. SidenotePart 2, oct-april, doc 42

The statement with all individual signatories visible can be found here.

The letter contained hardly any scientifically founded arguments about agriculture or even biotechnology. The letter was more concerned with EU regulations as an obstacle in the innovation race or for competitiveness.

The VIB has been actively involved in the lobby campaign for the deregulation of new GMOs for many years. The institute has Bayer and BASF in its board, and its researchers often have vested stakes in the technology through patents.

VIB’s Scientific Director Dirk Inzé emphasized in an opinion article that the EU-SAGE letter is “proof of a solid consensus among the academic life science research community that we need to act to safeguard the future of genome editing”. However, Inzé only talked about alleged benefits of the technology such as contributing to the challenge of climate change or to deliver more nutritious crops, but did not once mentioned the risks. Instead he raised the spectre of brain-drain and claimed that the EU GMO rules are an impediment to innovation.

But the question is, does EU-SAGE really represent “129 research institutes” as it claims on its website, in communication with decision-makers and in the media? It certainly helps to create a halo of scientific authority around the deregulation position. However, a closer look shows that many signatories do not represent a research institute:

- In at least 49 cases, support for the lobby letter comes from one or a few individual researchers, or from a head of faculty or department – not from someone who could represent the institute as a whole.

- The legal department of the Université Libre de Bruxelles (ULB) wrote a letter emphasizing that the use of its logo in this case was “potentially misleading” because it “falsely gives the impression that the position enjoys broad support from a range of universities, including ours, which in the case of the ULB is certainly not the case”. The head of the Université catholique de Louvain (UCL) too indicated that this form of communication leads to confusion.

- At the Belgian university Vrije Universiteit Brussel, a small committee was set up to decide whether the academic institution could sign the request. PRRI-lobbyist Piet Van der Meer – a guest professor at VUB – was invited to join that committee. He strongly argued in favour of supporting the letter, using arguments of world hunger and the claimed benefits of new biotechnologies. The rectorate ended up issuing its own statement, expressing a similar position as the EU-SAGE letter.

- In several cases, the signatory is not a research or scientific institute. For example, the Associazione Luca Coscione and the related platform called ‘Science for Democracy’ are not research institutes. The latter is a platform composed of some individuals, with the stated aim of defending the “Right to Science as a structural component of Liberal Democracies”. In March 2019 the group organized a stunt in front of the European Parliament, apparently handing out illegal CRISPR rice snacks, until an official of the Belgian food inspection ended it. There is no information available about the group's funders. Meanwhile, the Romanian Seed Industry Alliance is a platform for the seed industry. The European Federation for Biotechnology (EFB) calls itself “the independent voice of biotechnology in Europe”, including for biotech companies, but does not conduct any research itself. The EU Life is a consortium whose participating institutes are already on the list, so this signature is duplication. The same goes for an Italian technology platform called Plants for the Future.

In this case, a lobby letter signed by scientists from one discipline is being deliberately portrayed as the viewpoint of the broader scientific community, in the hope that this will have a political effect. This is not a unique case.

Scientist letters serve industry interests

It is not the first time that a sign-on letter by scientists has served narrow industry interests. A well-known case is described in a report by French journalist Stéphane Horel and Corporate Europe Observatory. In June 2013 a letter was sent by a group of 56 scientists, led by German toxicologist Wolfgang Dekant, to the Commission’s then-Chief Scientific Adviser Anne Glover. The letter took aim at a new policy to fight hormone disrupting chemicals, developed by the Commission’s Environment division. This letter was forwarded to the Secretary-General of the Commission at the time, who used it as an excuse to delay and derail the new policy, at great cost to public health and the environment.

Another example is the Heidelberg Appeal, a document released by a group of climate-change deniers at the time of the Earth Summit in Rio de Janeiro in 1992. The appeal did not directly address climate change but nevertheless aimed to undermine the scientific conclusions of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) on global warming. It was signed by 492 scientists including some Nobel Prize winners, and was promoted by the fossil fuel and other polluting industries to manufacture doubt about the need for environmental action.

Extensive Industry Lobbying of the Commission since the ECJ ruling

The CRISPR-files also include large batches of documents on the subject of genome editing and its regulation, obtained through Freedom of Information requests to the European Commission since July 2018. These documents include communications by the Commission with industry, NGOs, EU member states, the US and Canadian authorities, amongst others.

All documents are now publicly available.

These documents show that a very broad set of agribusiness groups lobbied the Commission since the ECJ ruling in July 2018. This included, for instance, the starch, vegetable oils, chemicals and animal feed industry, but also maize and sugar beet growers.

The Commission however repeatedly pointed out that industry should present concrete evidence of benefits of the new generation of GMOs. In a letter to the German food industry, Health Commissioner Kyriakides urged them to "engage constructively in open debates with national regulators, scientists and stakeholders, including consumers, on the potential risks and benefits of new techniques". She also thought that such debates should "cover ethical, legal, societal and economic aspects.”

Several of the lobby groups made remarks SidenotePart 2 / Oct 2019 - April 2020 - 4 / doc 64 suggesting that pesticide reduction would not be achievable without genome edited crops. However, the organic and agroecological sectors have since long developed and relied on production methods that do not rely on pesticide use or GMOs.

On 18 June 2020, Commissioner Kyriakides attended a meeting SidenotePart 3 / doc 21 of Copa-Cogeca’s highest leadership to discuss the Farm to Fork Strategy. One Copa-Cogeca representative told the Commissioner that European farmers are “losing out on the world market” because they do not have access to the same tools (ie genome editing) as their competitors. This is a tall claim - so far there is no evidence that EU farmers are facing hardship because they do not grow GMOs. Other factors like market liberalisation are a much bigger threat to European farmers' livelihoods.

The lobby documents released by DG Agriculture show that former Agriculture Commissioner Phil Hogan had external meetings on this topic only with industry and industry-linked institutes (twice with DowDupont/Corteva, once with animal feed lobby FEFAC and once with the VIB).

The lobby documents received from DG Trade show that the US frequently puts pressure on the EU in WTO meetings, insisting that it should adopt the position outlined in a statement by the EU’s ‘chief scientific advisors’. This group of advisors belong to the Commission’s Scientific Advice Mechanism (SAM). On the initiative of some members, without a request from the Commission, this group wrote a statement that echoed a number of industry claimsabout the new genome editing techniques. This included the flawed argument that because the techniques are more precise, the resulting GMO is also more safe.

In September 2019 DG SANTE official Anne Bucher (DG SANTE) was invited by the American European Community Association (AECA), according to its website an “established and trusted high-level forum where senior business leaders and policy-makers meet together to examine and discuss issues and challenges of common interest and concern”. AECA is backed by a large number of multinational companies, lobby groups and lobby firms, including Croplife Europe, ExxonMobil, Microsoft, Philip Morris International, FTI Consulting and FleishmanHillard.

In preparation of that meeting, Ms Bucher was reminded by her services that then-US President Trump had asked the United States Trade Representative (USTR) to develop an “international strategy to remove unjustified trade barriers and expand markets for products of agricultural biotechnology”.

Since the ECJ ruling, the regulation of genome editing was regularly topic of discussion at meetings between the EU Health Commissioner and DG SANTE, and high-level officials of the US, Canada and Argentina. It is hardly a coincidence that these countries are among the largest GMO exporters in the world. SidenotePart 4 / SANTE 2018 - 2019 / LIST OF DOCUMENTS

Broad societal debate is essential

The biotech industry and its allies are working hard to convince and mislead the EU institutions into believing that the new generation of GMOs are so safe that they do not require regulation.They are also spinning a tale that the new GMOs will succeed where previous ones failed: in promoting a fair, socially just and ecologically sustainable agriculture. If the industrial lobby effort succeeds, then new GMOs (plants, animals, fungi and micro-organisms) will no longer undergo food and environmental safety checks, nor be monitored or labeled.

However, there are much more appropriate and innovative solutions available to make agriculture more environment- and climate-friendly, such as those developed by organic farmers and agro-ecology networks. Crucial first steps for instance include the increased use of trees in farming, more genetic diversity in crops and animals, localised production, soil and water conservation, natural pest control, lighter machines, more rotation of crops, and less intense animal rearing. This will equally enable farmers to stop being dependent on expensive seeds and polluting pesticides, as offered by Bayer, BASF, Corteva and Syngenta.

The lobby campaign described here, that largely remained under the radar, is no less than an assault on the EU’s environmental and consumer protection legislation, which contradicts the Commission’s Farm to Fork ambitions for environmentally friendly agriculture and consumer choice.

Environment and farming groups call on the EU institutions to ensure that the 2018 ECJ ruling is fully implemented, thereby keeping new GMOs covered by current safety controls and labeling rules. This topic will be high on the EU agenda in the coming months, and it is crucial that the the wider public is actively involved in this debate. The future of our food system concerns everyone.

More background information

Corporate Europe Observatory has been tracking the industry’s lobby attempts to get new GM techniques deregulated since 2015, and has built a collection of documents going back to 2012. Our first report on the topic, published in 2016, explained how companies and research institute steamed up in the ‘New Breeding Techniques Platform’ to pressure the European Commission to deregulate most, if not all, the new (GM) techniques.

A second article we co-authored exposed how the European Commission shelved a legal opinion confirming that at least some genome editing techniques would fall under EU GMO law, following pressure from the US government. We also uncovered how the global seed lobby developed detailed tactics and PR tricks for its members to use in their communication about new GM techniques. Misleadingly, they claimed that these techniques are no different from plant breeding “that humankind has done for thousands of years” and are “basically just boosting Mother Nature to a degree”.

A new report published by the Greens/EFA in the European Parliament rebuts the hyped claims made by industry for these techniques – for example, that genome editing is precise and safe, that it is widely accessible for everyone, and that it will play a crucial role in meeting the challenges of climate change and food security.

Techniques like CRISPR are genetic modification techniques and need to be subject to safety checks as they can produce unintended effects and as the resulting organism can have different biological characteristics, even if no DNA from another species was introduced. As the German organisation Testbiotech argues, "if a large number of these New GE organisms are released within short periods of time, they may become disruptive to ecosystems and severely endanger biodiversity".

To understand the context of the GMO debate, it is also important to keep in mind that:

- Since December 2015 the European Parliament has voted 50 times on objections to GM crop authorisations for import, with up to 71 per cent support in favour. For instance in May 2020, 477 MEPS from all political groups supported a resolution opposing the authorization of a GM soybean tolerant to 3 herbicides (glyphosate, glufosinate, and dicamba). SidenoteSee page 150 of: https://www.europarl.europa.eu/doceo/document/PV-9-2020-05-13-RCV_FR.pd…]

- Nineteen EU member states have decided not to cultivate the few allowed GM crops on their territory.

Timeline of upcoming events:

- By 30 April 2021: DG SANTE of the European Commission plans to publish a study on genome editing, as requested by the Council under the Finnish Presidency.

- May and June 2021: Member states will discuss the study in the Agriculture Council and the Environment Council.

- June and July 2021: The votes on the European Parliament’s Farm to Fork report in June (committees) and July (plenary) will also be relevant to this issue.