Stay always informed

Interested in our articles? Get the latest information and analysis straight to your email. Sign up for our newsletter.

Six years ago we sounded the alarm on the Energy Charter Treaty with an in-depth report and campaign showing how it is a serious block to climate action. In a milestone moment we celebrate that the EU has now confirmed its exit from the Treaty.

EU withdrawal from Energy Charter Treaty is a success for civil society

In a milestone win for civil society, the European Parliament’s voted on 24 April 2024 to adopt the Commission's proposal that the EU withdraw from the Energy Charter Treaty (ECT), showing that campaigning and movement building really does work. The Belgian EU Presidency reached a deal with the European Commission and member states on the EU’s withdrawal from the ECT, an international treaty protecting fossil fuel investments. This has now been approved by the European Parliament.

The treaty was designed in the 1990s to favour industry’s interests, and was a powerful weapon to obstruct the kind of phaseout of fossil fuels needed to avoid catastrophic climate change. It should never have existed in the first place.

Corporate Europe Observatory was one of the first to expose the dangers of the ECT and the powers it gives the fossil fuel industry. Our pioneering work helped raise awareness and kickstart the campaign for withdrawal from this damaging treaty, especially in the years when it was little known or understood. Global treaties like the ECT are often complex and opaque, and we worked with allies to demystify it and expose just how it could halt much needed action to advance the energy transition. We have to credit our former trade expert Pia Eberhardt in particular for putting the issue on the map.

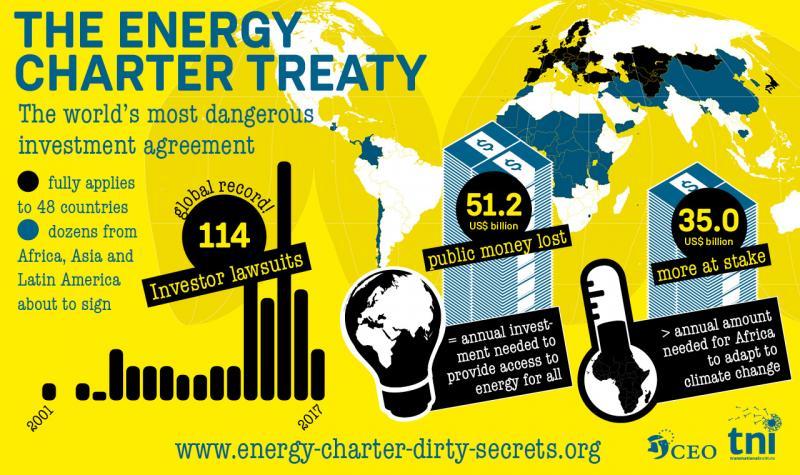

Our research alerted decision-makers and activists to the fact that with an investor-state dispute settlement mechanism (ISDS) at its heart, the ECT is an extremely dangerous instrument in the hands of the fossil fuel industry. The ECT allows foreign investors in the energy sector to sue governments for decisions that might negatively impact their profits. That includes climate policies,

for example in 2017 Canadian energy giant Vermilion sent a legal letter threatening to sue France before ISDS courts, after French Environment Minister Nicolas Hulot proposed a draft law to end fossil fuel exploration and extraction on all French territory by 2040. Following this pressure the French Government made a reverse course and modified the law.

The ECT’s legal regime favours investors, is unpredictable, and the fines that governments can be hit with are catastrophically large. We argued it gives unacceptable legal options and influence to the dirty energy industry, in turn creating strong incentives for governments to delay, weaken, or drop the phaseout of fossil fuels. In our view, the treaty was one of the most powerful obstacles stopping governments from tackling climate breakdown.

By withdrawing from the Energy Charter Treaty, the EU draws a line beyond which the treaty cannot influence decision-making.

Unfortunately, however, the ECT does have a sunset clause still granting the fossil fuel industry years of access to private arbitration via ISDS. Cases of corporations suing governments over the transition away from fossil fuels will therefore still need to be watched out for. This does not take away from the fact that the EU’s withdrawal is a major success for civil society and everyone who campaigned against the Energy Charter Treaty.

Other neoliberal obstacles

The 1990s – when the Energy Charter Treaty was forged – were peak neoliberal years. Just as with the ECT, many other problematic treaties and European legislation were forged in that era, that lock in corporate privileges, and create obstacles for the socially just ecological transition Europe needs. It's not just the ECT and other international investment treaties enabling ISDS, but all of these outdated approaches that need an urgent review.

That includes lots of outdated neoliberal mechanisms in EU treaties and legislation. Take the EU’s Single Market and its enforcement system. As we show in our July 2023 report, corporate interests use little-known Single Market enforcement mechanisms to block or undermine progressive legislation at the national and municipal level across the EU. Companies, lobbyists and industry associations use these enforcement mechanisms to submit complaints and thereby get the European Commission to investigate national legislation for potential breaches of Single Market law. Unlike the ECT, corporations cannot at least demand financial compensation, but their complaints in many cases result in delaying, weakening or blocking of the much-needed social and ecological initiatives.

For example the French Government’s ban on short-distance domestic flights that could easily be done by train have provoked complaints by aviation lobby groups to the European Commission. In response these urgently needed measures have been restricted in scope. Now, due to complaints by airport lobbies, the Commission intervened against the Dutch Government’s plans to shrink flights at Schiphol airport by 10 per cent, using Single Market law as a justification. How does this square with the EU's own commitments to reduce CO2 emissions by 55 per cent by 2030?

If this isn't bad enough, industry associations including BusinessEurope and the European Roundtable for Industry (ERT) are on a full-scale campaign to eliminate what they refer to as ‘regulatory barriers’, which are in many cases entirely legitimate laws and policies. A new corporate lobbying coalition (of which the ERT is a member), Europe Unlocked, claims it is "issuing an S.O.S to the Commission, Member State governments and an incoming Parliament: Strengthen our Single Market" with a focus on deregulation and "competitiveness". A key demand in these campaigns is for the Commission to gain stronger powers to act on corporate complaints and enforce their interpretation of Single Market legislation. Unfortunately, these industry lobby campaigns are being warmly welcomed by many EU decision-makers, lured by the claims that ‘completing the Single Market’ would result in hundreds of billions of euros-worth of additional economic growth. In other words, instead of protecting the democratic space of public authorities, or prioritising climate action, the EU is going in the opposite direction.

This is also the case with the EU's so-called 'Better Regulation' agenda which we have seen operate in everything from the Dieselgate scandal to the retreat of chemicals regulations. This involves big business interests taking centre-stage in the considerations of policy-makers, and those with the most lobby power get the biggest say. If you care about the environment, workers’ rights, or public health, the EU's 'Better Regulation' approach is highly concerning, as it is being used to weaken or abolish current rules, while significantly hampering or even stopping the introduction of new ones.

Europe really needs to learn some important lessons from the ECT. In the same way that the EU has finally recognised the Energy Charter Treaty is incompatible with the Paris Agreement and its own climate targets, it needs to apply the same logic to many other areas – from Single Market rules to 'Better Regulation' – which put the needs of investors and corporations over all other considerations. Indeed, if the EU is serious about tackling climate change and ecosystem breakdown, it needs a rollback of the kind of corporate capture of EU policy-making that we see endemic in many crucial areas. We need public policies to quickly and equitably phase out fossil fuels, but lobbyists from the coal, oil, and gas industries are slowing us down to protect their own profits. That means not just removing these neoliberal structures – withdrawal from the ECT being just the first step – we also need a firewall between these dirty energy lobbyists and political decision-making.