Authoritarian right: UK

Since the UK voted to leave the EU in the 2016 referendum, UKIP has lost its mojo as a one-issue party, although the Conservative Government’s failure to deliver Brexit may help to revive its fortunes.

Click here to read the full report, or check out our methodology and data set

In its pre-referendum heyday, UKIP took first place in the UK’s 2014 European elections. UKIP prided itself on its anti-establishment image, talking up its ability to attract support from Labour’s working class core in former industrial heartlands. Nigel Farage, UKIP’s most famous, or should that be infamous, leader has talked about reaching out to “lorry drivers and building site workers, butchers and bakers, farm labourers and security guards, shop assistants and cleaners”, and hearing their concerns which included: “wages falling ever further behind the cost of living for year after year … hard-working people being dragged into hardship.”

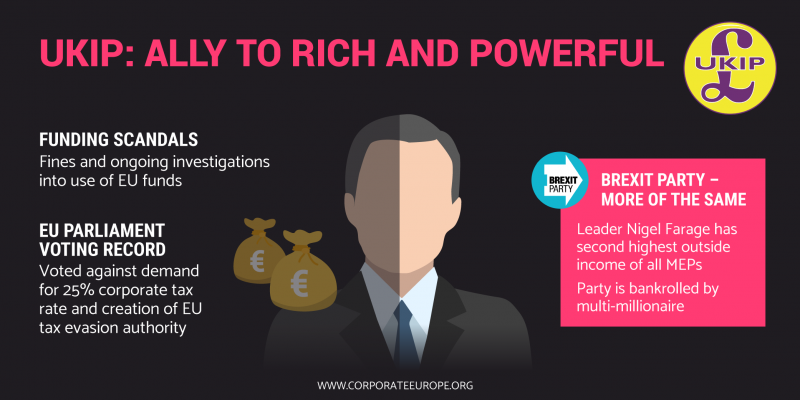

However in reality an important part of its support base has always consisted of disaffected middle-class Conservative voters, while UKIP’s donors and the positions adopted by the party have reflected its close ties to the rich and powerful.

UKIP’s donors and the positions adopted by the party have reflected its close ties to the rich and powerful

Funded by the wealthy ...

UKIP has repeatedly managed to attract significant funding from ultra-rich individuals. Major declared donors include businessman Paul Sykes, via property company the Highstone Group; Arron Banks, via the insurance-related Rock Services company (see below); Media mogul Richard Desmond who gave UKIP £1 million via his Northern and Shell media group; manufacturer Techtest; Stuart Wheeler who made his fortune in the gambling industry; and Ko Barclay, the property developer and son of the Daily Telegraph owner; but there are many others. Over the years, these donations have added up to millions of pounds.

… and voting accordingly

A preference for the interests of big business over workers’ rights is reflected in UKIP MEPs’ voting records in the European Parliament, reflecting its hypocrisy, according to our research. Its 2017 national election manifesto said: “We will not let large companies get away with paying zero or negligible corporation tax. When we leave the EU, we will close the loophole allowing businesses to pay tax in whichever EU or associated country they choose, and bring in any further measures necessary to prevent large multinational corporations using aggressive tax avoidance schemes.” And yet, given the chance to vote for the creation of an EU tax evasion authority, UKIP MEPs did the exact opposite, also opposing country by country reporting of corporate profits; and a 25 per cent corporate tax rate. While UKIP claims to stand-up for working people, its MEPs voted against proposals to support action on work-life balance; a proposal for a directive on ‘decent work’; an EU framework on health and safety at work; and action to tackle the gender pay gap.

UKIP opposed the phase-out of subsidies for fossil fuels and action to boost environmental justice, with Adelphi labelling it a denialist / sceptical party on climate change. UKIP voted against all the EU climate and energy policy proposals analysed by Adelphi between 2009 and 2018.

Scandal-ridden

Like others of its ilk, UKIP’s use of its EU funding has been subject to much controversy. While UKIP MEPs have railed against “corruption” in the EU institutions and across member states, they have misused EU funds themselves. For example, UKIP MEPs have deployed full-time European Parliamentary assistants for national political work, which is against EU funding rules. A UKIP MEP stepped down after being asked to repay over €100,000, while Farage was penalised €40,000 from his pay in 2018.

A UKIP MEP stepped down after being asked to repay over €100,000, while Farage was penalised €40,000 from his pay in 2018.

Never mind; he can afford it. Farage comes second in the list of MEPs with the highest outside earnings, thanks to his lucrative media work. Steven Woolf, who was elected as a UKIP MEP, but who now sits as an independent, also declares up to €12,000 extra annual income from consultancy work, but it is not clear for whom, or on what, he consults.

EU funding to UKIP-supported political groups, including the Institute for Direct Democracy in Europe (IDDE) and the Alliance for Direct Democracy in Europe (ADDE), has now ended after €173,000 had to be repaid after being misspent on national campaigning, including a doomed attempt to elect Farage to the British Parliament. In 2018, European Parliamentary authorities demanded that the IDDE repay an additional €668,620. ADDE is now insolvent and has not been eligible for EU funding in recent years; its vice-president was Mischaël Modrikamen, the Belgian far-right politician and friend to Steve Bannon (see Box 4). OLAF has confirmed to Corporate Europe Observatory that it continues to investigate ADDE and IDDE’s use of EU funding. However, the UK’s Electoral Commission cleared UKIP of wrong-doing on this specific matter, noting that “we are required to be satisfied beyond reasonable doubt that an offence has been committed”.

Earlier this year, Nigel Farage launched the Brexit Party, taking 13 other UKIP MEPs with him. Funded by the multi-millionaire financier Richard Tice who also serves as party Chair and who co-founded the pro-Brexit Leave.EU campaign, the Brexit Party simply presents more of the same. It is predicted to win the most MEP seats in the European elections.

BOX 6: Funding the ‘Leave’ campaigns in the 2016 Brexit referendum

A Transparency International report has highlighted the role that major donors played in the funding of both sides of the 2016 Brexit referendum, with more than half the total funds spent coming from just ten donors. While some of the donors supporting the ‘Leave the EU’ campaigns were not well-known, such as manufacturing company-owner Diana Van Nievelt Price, others are, including the now notorious Arron Banks. Banks was the single biggest donor to the Brexit campaign but journalists and MPs have raised concerns that not all of this money was Banks’ own to donate and query whether it came from UK or overseas sources. Overseas political donations in the UK are banned. In late 2018, Banks’ activity for the Leave campaign, including contacts with the Russian Ambassador to the UK, were referred to the National Crime Agency and its investigations are ongoing. Banks has said: “There was no Russian money and no interference of any type”.

But this is just one of many questions hanging over the Leave campaign. Guardian and Observer journalist Carole Cadwalladr has spearheaded investigations into how political campaigns around the world, including the pro-Brexit Leave, illegally used and abused Facebook data, as part of its collaborations with the now defunct consultancy Cambridge Analytica and a complex web of partners. At the end of March 2019, Vote Leave dropped its appeal against a fine, levied by the UK Electoral Commission, for over-spending during the 2016 referendum.

Click here to read the full report, or check out our methodology and data set