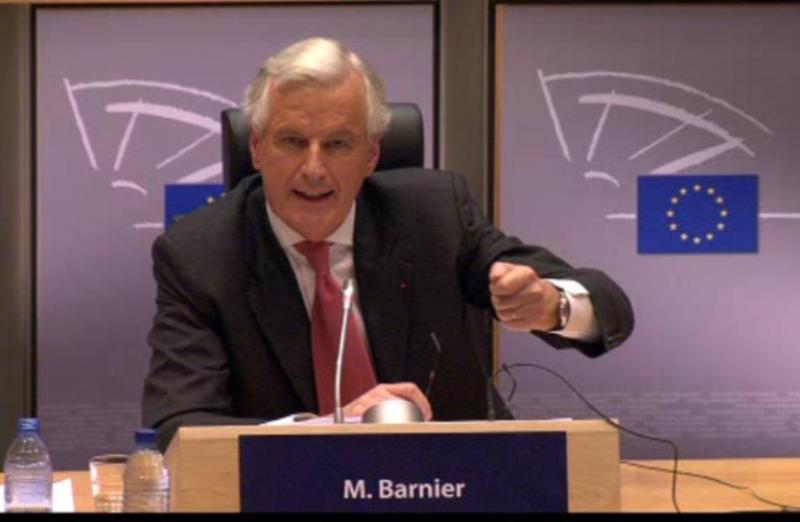

Barnier’s ban on meetings with lobbyists

Commissioner Barnier has surprisingly announced a temporary ban on meetings with the financial lobby. An important and telling step, but more is needed if the objective is to curb the lobbying power of the banks.

On the 17th of December Der Spiegel carried a story on a remarkable step taken by Single Market Commissioner Michel Barnier. Simply, the Commissioner had asked his staff not to accept any meetings with financial lobbyists for the time being: “In view of our workload and the sensitivity of our current dossier, until instructed otherwise Market D.G. employees should not meet with bankers, their representatives or their associations,” an email from the General Director of Barnier’s department, DG MARKT (Directorate General for the Single Market), reads. It seems the ban will be upheld till the 29th of January, the day when Barnier is set to release a proposal on bank structure in the EU.

When asked why this ban was imposed, the Commissioner’s spokesperson Chantal Hughes responded that DG MARKT was due to work on two pieces of legislation: the outstanding issues on the banking union and a proposal on a split between banks’ investment and retail departments. In both cases, consultations have been carried out, and banks “have been widely heard and listened to,” she added. That makes you wonder just how many meetings have taken place at DG MARKT over the last months. Most appropriately one MEP is using the occasion to ask Barnier to announce his meetings with lobbyists.

A welcome step

The move has been met with anger from lobbyists, according to the British Daily Telegraph. “For us, it’s a bit bizarre that the Commission has chosen to isolate itself in this way,” a senior bank executive “at a major international lender based in London” said to the paper.

Others, including Corporate Europe Observatory, support the move strongly. It’s about time the financial lobby is met with clear and official blocks in their large scale effort to shoot down any kind of meaningful regulation. The question is not why Barnier has taken the unusual decision, as the evidence speaks for itself: financial lobbyists have been successful in significantly curbing attempts to strengthen financial regulation during the whole reign of Michel Barnier; any proposal of importance from his office has borne the marks of heavy lobbying, and all credible ideas for containing the destructive powers of financial markets were stopped in their wake. Whether it’s banking regulation, standards for hedge funds, or rules on derivatives, accounting or credit rating agencies, the financial lobby has managed to capture the agenda at the earliest possible stage – in Michel Barnier’s office.

Why now?

The real question, then, is not “why”, but “why not before”? Certainly the present dossiers are “sensitive” – with a banking union supposedly set up to control future collapses of banks and the introduction of rules to ban reckless speculation with bank customers’ money. But there have been many other “sensitive” proposals that called for similar measures, yet lobbyists always found an open door in Barnier’s quarters, which they managed to exploit to the fullest. For instance, the banking lobby managed to ensure that the draft EU version of the international Basel guidelines on banking regulation was considerably weaker than its source, and this characteristic made it way through the whole decision process. And with EU banking regulation weaker than elsewhere, the EU undermines the international guidelines, and adds pressure on governments elsewhere, not least in the US, to soften their approach. Generally, the long battle on the response to the financial crisis of 2008 was won by the financial lobby, and Barnier’s office should take much of the blame.

Admittedly, Michel Barnier has, on occasion, challenged the financial lobby. In fact, already at the hearing in the European Parliament back in January 2010, when searching for support for his nomination, Barnier made two positive statements: one in which he vowed to fight financial speculation in food prices, and another where he promised to open up the important advisory groups on financial regulation, so far dominated by the financial lobby, to broader participation.

Halfhearted measures

On the face of it, something has indeed changed. The ratio of non-financial lobby participants in advisory groups has gone up. But it seems that whenever it counts, the devil is in the detail, and one amazing example is indeed on food speculation, the very topic Barnier had spoken passionately about at the hearing in the European Parliament. According to the official register, no particular expert group had been set up on the topic within DG MARKT, leaving Barnier clean on the question of unbalanced expert groups. But when a proposal was finally tabled in October 2010 (the Markets in Financial Instruments Directive & Regulation), the accompanying documents showed that a number of “workshops” had been organised with “stakeholders” – with a workshop on commodities/food speculation dominated by the financial lobby. In the end, Barnier tabled a proposal that didn’t meet the minimum standard: that of rules as strong or stronger than the corresponding US rules. The EU again found itself in the rearguard and will remain there on the life-and-death issue of food speculation, according to the latest news from the ongoing negotiations in the Council.

Also, Barnier has made welcome statements on transparency, as when he announced willingness for all DG MARKT meetings with financial lobbyists to be made public on his website. Yet nothing has happened so far. Hopefully Barnier will make sure this happens soon, and certainly before the end of his term later this year.

Clearly the case on the so-called Liikanen Group - one of the the sensitive topics that lead to the ban - is an exception to the rule. Here, for the first time in the history of EU financial regulation, an important advisory group not dominated by the financial lobby was established to give advice on the structure of the EU banking sector. The resulting Liikanen report certainly had its weaknesses, but it was the most far reaching conclusions from any group set up by the Commission, including a proposal to separate banks’ investment departments from their retail departments. Clear evidence of how reducing the presence of the financial lobby in expert groups can lead to positive and effective regulatory recommendations.

A rethink is necessary

Now that Barnier has taken a step further and put an end – at least temporarily – to the constant pressure from banks on his staff, all seems well, you would think. The problem is that the ban is hardly an attempt to defend a proposal along the lines of the far-reaching Liikanen report, but at best to stop the further watering down of something much weaker. It would have had to be applied much earlier if DG MARKT intended to keep the ambitious vision outlined by Liikanen. According to the press, Barnier’s proposal has already been tailored to meet the demands of the banks, and the promise of a US style Glass-Seagall Act which decades ago forced the separation of investment banks and commercial banks has vanished.

The ban, then, seems to be little more than a desperate cry for a working space, not a fully-fledged attack on the power of the financial lobby. It bears clear witness to the ability of the financial lobby to disrupt and influence the work of officials on financial regulation, but it’s hardly a genuine attempt to curb their power. Rather, the story shows us once again that whatever personal qualities and preferences a Commissioner might have, what matters in the end are clear mandatory rules on transparency, rules that put an end to lobbyists domination of expert groups, and rules on their conduct in general.

The logic behind the (temporary) ban makes complete sense: the financial industry had already had ample opportunities to provide input and voice their concerns. Barnier's move should be used as an occasion for a broader rethink of the Commission's relations with industry lobbyists, not least with banking lobbyists. Banking lobbyists might think that they have a god-given right to an unlimited number of one-on-one meetings behind closed doors with Commission officials, but obviously this is just a bad habit that developed during the pre-financial crisis years. As one example of an effective change, after the consultation phase on new legislative proposals – where everyone is invited to provide input – meetings could be limited to hearings that involve different stakeholders. Breaking with the old, bad tradition would surely be good news for the chances of effective financial market regulation in the public interest.

Comments

Thanks for your effort to keep us uptodate on financial and corporate affairs.

If someone of you can read Spanish, please check references to your work on my last book about financial lobbies and many entries in my blog.

I consider the temporary ban to lobbyists being quite a remarkable single measure. I hope other DGs recognize they could do the same and actually make clear how heavy a pressure from the lobbies lies on the EU officials. This would support the requirements for mandatory and sufficiently detailed registers of lobbyists' visits.

With banks across the World, not just the EU or UK, ripping off anyone it can; and with unemployment still high because of their recklessness, then it seems logical that some link between their pay and the performance of the wider economy they work in will change what is in their best interests.

How long have we heard the cry that the financial sector is divorced from the real economy?

My simple proposal (UK context, but easy to apply EU wide) is to dynamically set banker's top-rate of income tax to ten times the unemployment percentage rate; and to set the bank-levy to the cost to the state of Jobseekers Allowance (unemployment benefit).

In 2007 this would have been around 50% & £1.7bn

In 2009 peak unemployment, 83% and £6bn.

See www.bailoutswindle.com for details, and email if you have any questions or critiques!

Also: https://twitter.com/HarryAlffa/status/384617899018551297

to see Prof D Bell's

http://rms.stir.ac.uk/converis-stirling/person/11421

agreement with the idea.