Summer package does little to refresh EU's failing climate policy flagship

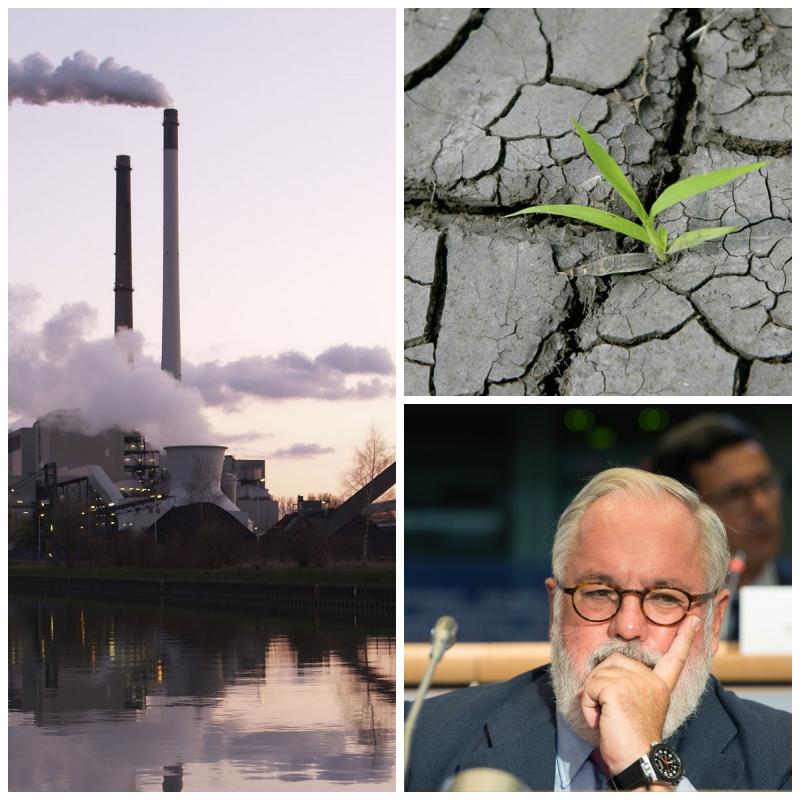

Like a good break in the sun, the European Commission's “summer package” was meant to leave climate and energy policy refreshed, not least the failing Emissions Trading System (ETS). But the reforms announced by the Commission do little to address the flaws in its flagship policy, which turned 10 this year.

The headlines that the Commission wanted to write focus on the increased pace at which emissions covered by the scheme are supposed to reduce. In line with the 2030 Framework for Climate and Energy Policies agreed last October, those targets rise from 1.74 per cent to 2.2 per cent annually for the power generation and manufacturing sectors covered by the scheme. That's a long way short of what the EU needs to be doing if it's to take on its fair share of actions to avoid dangerous climate change, however.

Increasing the emissions target does not mean the system will automatically be effective. Past experience has shown that the ETS sets a ceiling on climate ambition, rather than ratcheting up the requirements on industry. But it has never met its intended aim of setting a price on carbon that could encourage polluters to clean up their act.

With carbon prices remaining low, it is clear that the ETS was not behind the 17 per cent drop in emissions for sectors covered by the scheme since it began in 2005. There are no shortage of other candidates to explain that: the outsourcing of manufacturing beyond Europe in search of cheaper labour, the economic crisis after 2008, changes in commodity prices, new technologies and in some cases other climate policies, such as renewable energy feed-in tariffs and energy efficiency targets. But the ETS has consistently been invoked to undermine those very policies, on the grounds that their success might further weaken the carbon price.

The contradiction between carbon trading and more effective climate policies gets to the heart of the problem with the Commission's current proposal. The ETS serves to protect big industry instead of forcing it to clean up its act, handing out free emissions allowances that exempt them from reducing emissions. Back in January 2008, the Commission promised that there would be “no free allocation” by 2020. But its latest proposal will continue to offer free allowances to 50 industrial sectors until at least 2030. The precise details won't be known until 2019, but they are expected to include the steel, cement and chemicals sectors.

The rationale for free allowances is that EU firms are at risk of “carbon leakage,” with industry relocating to higher polluting countries as a consequence of the scheme. Yet Commissioner Cañete admitted, in the press conference to launch the new ETS proposal, that “there has not been delocalization of industry caused by the price of carbon.” By offering substantial subsidies in response to a problem that the Commission knows doesn't really exist, it is pandering to industry rather than addressing environmental concerns.

The Commission proposal also confirms that the Market Stability Reserve, a recent agreement to adjust the massive oversupply of allowances available on the EU's carbon market, could return 250 million surplus permits to the market.

In addition, the new proposal allows for the continuation of a controversial system of offering free allocations to the power sector in Central and Eastern Europe in return for “modernization” that has often meant little more than refurbishing coal-fired power plants.

It doesn't need to be like this. From emissions performance standards on power plants to well-targeted renewables subsidies, there are plenty of other climate policies that would be more effective than the ETS. In seeking a new mandate for emissions trading until 2030, the Commission has moved to stifle those possibilities.

Oscar Reyes is a researcher with Corporate Europe Observatory and co-author of a book on carbon trading