The EU push for carbon markets

The EU Emissions Trading System has failed to reduce emissions, but that hasn’t stopped the Commission from pushing other countries into using carbon markets. The EU is building up carbon markets in China and elsewhere, often with the support of the World Bank. The Commission is also leading efforts to link the EU ETS to other systems, making a bigger carbon market with new ways for speculators to game the system for quick profits at the expense of the planet.

There are not too many things that the European Union can claim to be a world leader at these days, cheese making and bread baking aside. But the Commission makes a point of extolling its “global leadership” on climate change. In practice, the paucity of its climate targets belies this claim, falling way short of its fair share of global action. But it does take the dubious honour of leading the world in the use of carbon markets.

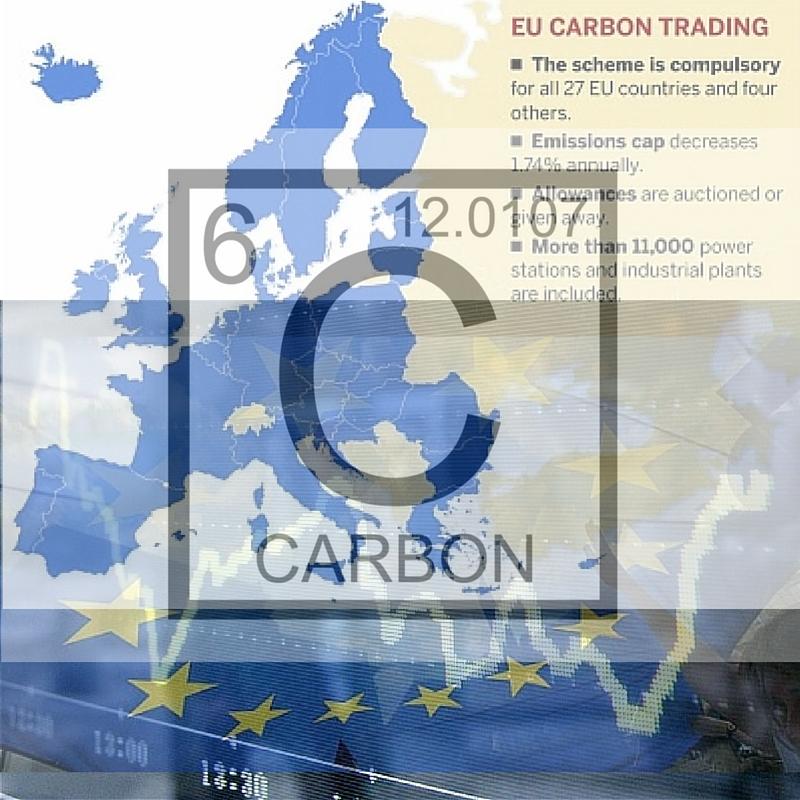

The EU Emissions Trading System (EU ETS) is the world’s largest carbon market, covering almost half of the bloc’s CO2 emissions. The record of the scheme is woeful, failing to reduce emissions and handing large windfall profits to some of the continent’s biggest polluters. Yet that has not stopped the EU from trying to export this failed model elsewhere.

United Nations climate negotiations, such as the COP21 talks taking place in Paris this week, used to be the main channel for the EU’s carbon market push. Europe’s carbon market swallowed up the vast majority of credits issued by two UN carbon offsetting schemes, which allowed countries to buy “emissions reductions” (in the form of carbon credits) from abroad and count those as their own.

As the list of problems and scandals surrounding UN offsets grew, the EU turned its attention to attempts to export versions of the ETS abroad. Commission officials thought they had achieved a major breakthrough at COP17, the UN climate conference at the end of 2011, where a “new market mechanism” was established. Their hope was that this would enable ETS-style schemes in various countries, with emissions limits set in particular industrial sectors (eg. steel in China), related to which companies could then trade permits to pollute.

But the UN’s new market mechanism was stillborn: in the absence of globally agreed climate targets, and in the face of strong opposition to the “commodification of nature and carbon markets” from Bolivia and its allies in the ALBA group of Latin American countries, the UN system has not acted to set up the new market.

The EU position going into the current UN climate negotiations is clear that “the Paris Agreement should allow for the international use of markets.” It continues to push for “common accounting rules” that would make it easier for the EU to link its emissions trading scheme with others emerging internationally.

At the same time, the Commission is pushing ahead with measures to promoting carbon markets irrespective of the UN talks. The EU is the main funder of the World Bank’s Partnership for Market Readiness (PMR), with the European Commission providing US$20 million and member states close to US$50 million to promote “market-based instruments” in 17 countries. The PMR funds the infrastructure (greenhouse gas registries, monitoring systems, etc.) that is required to create markets, as well as pilot and test schemes that it hopes will later expand.Its flagship measure involves promoting a national emissions trading system in China, which is due to be launched in 2017.

The EU is also providing more direct, and higher level political support to the creation of a national emissions trading system in China. Its bilateral climate cooperation measures, announced in June 205, include efforts to “further enhance existing bilateral cooperation on carbon markets, building upon andexpanding on the on-going EU-China emission trading capacity building project and work together in the years ahead on the issues related to carbon emissions trading.”

To some extent, the Commission is promoting carbon markets abroad to weaken the hand of industry critics who complain of “carbon leakage” - the idea (not backed up by evidence) that pricing pollution will force them to outsource industry beyond the EU’s borders. But the main result is simply to build a bigger carbon market, providing a means to lure big financial players back to a market that many banks quit in recent years. More carbon trades, happening more frequently, means a greater chance for the type of bets that speculators thrive on.

Bringing about this bigger market will require linking the EU ETS to other carbon markets, an approach that is now central to the Commission’s carbon market push. A deal to link the EU scheme with the far smaller Swiss ETS is due to be concluded by the end of this year. But while the EU has promised to exclude carbon offsets from its emissions counting towards a Paris agreement, the Swiss are committed to using international offsets to meet its carbon goals. That is symptomatic of the big problem with linking up carbon markets: where rules in one market can exclude certain activities on environmental grounds, linking can provide a backdoor that renders these fairly meaningless.

Carbon markets are no strangers to fraud, double-counting emissions reductions and other forms of gaming. The push for links between different schemes will make these risks even larger. The European Commission looks set to continue its efforts to link the ETS with other markets irrespective of the contents of a Paris climate agreement. It will promote these measures by saying they level the playing field and make carbon prices less volatile. In practice, a web of linked up carbon markets would result in a race to the bottom on environmental standards.

Instead of pushing carbon trading abroad, the Commission should own up to the failures of emissions trading at home.