Refusing to be accountable

Business hollows out new EU corporate social responsibility rules

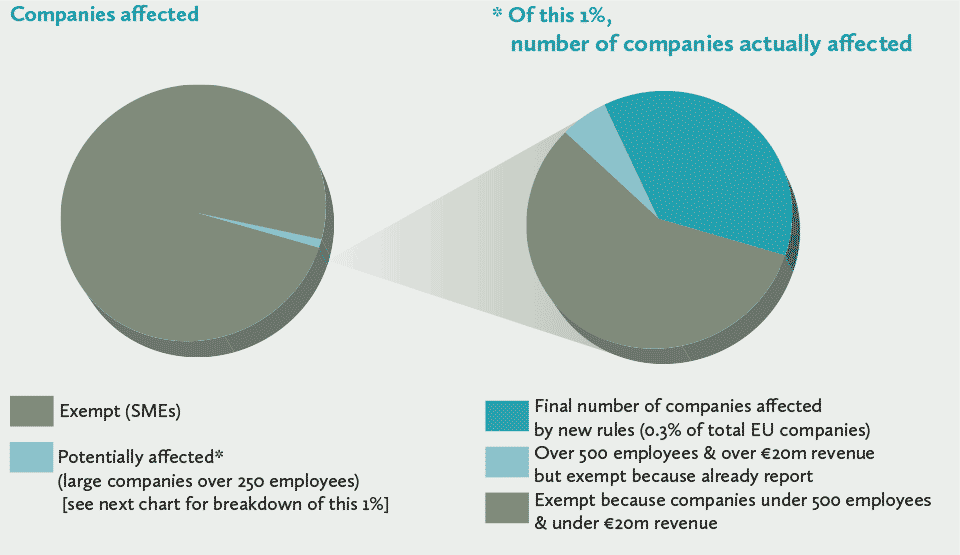

As a result of the economic crisis there is a widespread expectation that businesses should be more accountable to society. One important step in that direction would be to require companies to publish data on their social and environmental impacts across the supply chain. But the European Commission's new proposal on Corporate Social Responsibility reporting has been weakened by industry pressure to the extent that it is now virtually meaningless. Instead of a solid framework there remains a hollowed out structure not fit for purpose, to the point where a mere 0.3% of all European companies may be affected by the new reporting rules on social and environmental impacts – and even they could opt out. Business lobbies, with very active support from the German government, have successfully pushed for voluntary reporting with non-binding requirements that can be selectively interpreted and would not be enforceable.

Download this report as pdf here.

Crisis and responsibility

Popular calls to hold business to account for its irresponsibility in the wake of the 2008 economic crisis motivated the European Commission to review its policies on Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR)1, following similar moves by the United Nations2. This took the form of developing an initiative that would require companies operating within the European Union to report on their social and environmental impacts.

Although strongly welcomed by human rights, environmental, and pro-transparency campaigners, the initiative has been met with the utmost resistance by conservative sections of the business community who have long fought for a laissez-faire approach to CSR.

Spearheading this opposition has been a powerful German-led contingentof large corporations supported by the efforts of Merkel’s Government. Aided by Brussels’ most influential industry-lobby powerhouses, together they have successfully undermined the attempt to improve the accountability of industry to governing institutions and citizens.

Pressure from this powerful industry-government coalition appears to have been so successful that, as the initiative currently stands, it exempts many of Europe’s major transnational corporations from complying with rules for reporting on social and environmental impacts. The proposal, released 16 April 2013, makes a virtue of its own weakness:

[I]t takes a flexible and non-intrusive approach. Companies may use existing national or international reporting frameworks and will retain their margin of manoeuvre to define the content of their policies, and flexibility to disclose information in a useful and relevant way. When companies consider that some policy areas are not relevant for them, they will be allowed to explain why this is the case, rather than being forced to produce a policy3.

Civil society is concerned that weak reporting rules mean that CSR remains geared more towards public relations than transparency.

By reconstructing the policy process chronologically, aided by available documentation, online data and elite interviews, this report exposes how the Commission’s legislative proposals have come to be watered down and re-aligned with the interests of big business to avoid government intervention and public scrutiny.

However, despite the limited scope of the proposal, the fact that the reporting requirements will be – in principle – mandatory does suggest something of a cultural shift in the relationship between companies, regulators and citizens, which comes at a critical time for the legitimacy of big business.

Hiding the social and environmental costs

In 2011 Michel Barnier, European Commissioner for the Internal Market, initiated "a legislative proposal on the transparency of the social and environmental information provided by companies in all sectors"4.

Barnier’s proposal is a renewed attempt to improve companies' accountability to public institutions and citizens, as the European Commission had already attempted to introduce regulation of this kind back in 2003. However, due to strong industry opposition, aided by an institutional culture which favoured voluntary action rather than binding rules, that attempt resulted in a mere mention of vague reporting mechanisms for social and environmental impacts (also known as "non-financial reporting" or NFR).

The 2003 Directives called on Member States to require business to disclose information on environmental and social impacts in their annual and consolidated reports5. However, since these Directives did not provide a specific framework for the disclosure of this information, regulators from Member States interpreted them in a variety of ways. As a result, explains the European Coalition for Corporate Justice (ECCJ), a leading pan-European network of organisations that has been leading spearheading the campaign for improved corporate accountability, "The outcome is that NFR remains a voluntary exercise in most European countries"6.

According to studies conducted by the UK Accounting Standards Board, Deloitte, and Black Sun, amongst others, social and environmental impact reporting remains among the least well articulated in company annual reports7. As a result, the social and environmental implications of companies’ operations remain difficult to evaluate and compare, between countries as well as between industry sectors and individual companies.

PR or transparency?

As a result of these problems, the European Commission looked for solutions to provide the best possible legislative framework for social and environmental impact reporting. Between September 2009 and February 2010 they hosted a series of multi-stakeholder workshops on the disclosure of environmental, social and governance information (ESG) with representatives from business, investment funds, trade unions, human rights groups, governments, media and consumer organisations8.

Example: silence on forced labourVoluntary CSR reports can present positive ways companies have impacted society and the environment and yet ignore profound issues that ideally, this kind of reporting would reveal to public scrutiny. For example, in the European Commission’s summary report of the workshop it claims “The profits of forced labour are estimated at $34 billion annually, and 50% of those profits go to US or EU based companies. But CSR/sustainability reports do not provide information about this.”9 |

From the summaries of the various workshops it is clear that there is a major rift between the positions of civil society organisations and that of industry. According to civil society organisations, greater transparency of data relating to companies' social and environmental impacts is essential to hold them accountable to society yet, at present CSR/sustainability reports fail to provide such information. Instead, companies selectively report on positive aspects, whereby reporting is geared more towards public relations than transparency.

The civil society organisations present called on the European Commission to ensure that companies should report according to well-defined indicators and the success of the legislation should be measured on the basis of tangible reductions of negative social and environmental impacts of companies’ operations. They asked that the proposal for a mandatory requirement of CSR reporting should include:

(a) the identification of the company (including its position within the supply-chain, its sphere of responsibility and its products);

(b) information specific to the sector which the company belongs to;

(c) the environmental and social risks of the company’s operations (including measures taken to reduce those risks).

In contrast, business fudged, "Complete transparency, while arguably better than no transparency, can result in too much data … even hampering rather than facilitating organisational change."10 They claimed, "a basic platform and a common approach to ESG disclosure is necessary", while "legislation to make ESG disclosure obligatory is not".

As the Commission reports in its summary, "For some enterprises, a culture of greater openness and transparency would represent a big cultural shift."

No concrete reasons for opposing mandatory reporting of non-financial data were given, other than an ideological opposition to regulatory intervention on CSR maters. As one industry representative stated during the workshop, he would not report non-financial information "on principle"11.

An opaque process

As a follow-up to the stakeholder workshops, between November 2010 and January 2011 the European Commission held a public consultation on social and environmental reporting asking whether the legislative proposal should be for mandatory or voluntary reporting; whether it should include all companies or whether small and medium enterprises should be exempt; whether it should oblige companies to report on questions of human rights, corruption and bribery in relation to a company’s operations; whether it should develop specific standards for companies to follow in their reporting, or whether it should let companies choose for themselves which existing international (voluntary) standards best suit their reporting preferences12.

The Commission states that it received 259 submissions through the formal online consultation, as well as "others by email and letters"13.The former are available on DG MARKT’s website, but the latter are not14.Despite an Access to Documents request to release these additional contributions, DG MARKT has so far refused to make them publicly available – a decision Corporate Europe Observatory (CEO) is currently challenging.

It is still possible, however, to gain some insight into the nature of the views that shaped the Commission's proposal from the submissions publicly available, as well as interviews with officials and stakeholders involved in the policy process.

Business against mandatory reporting

According to the Commission, all stakeholders welcomed the initiative as a positive development,15 however there were major disagreements between different interest groups over its nature and scope. The question as to whether the legislative proposal ought to be mandatory or voluntary was particularly contentious. Whereas NGOs favoured a mandatory approach, industry favoured the voluntary nature of the current reporting system. Oil giant Royal DutchShell, for instance, stated that,

We would not support further mandatory disclosure requirements … We do not consider it would be useful or practical to develop specific mandatory EU measures for corporate reporting beyond the existing framework16.

Because Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) has traditionally been framed in voluntary terms within EU policy, "[a]ny mandatory requirement would be contradictory to the voluntary nature of CSR", argues EuroCommerce, Brussels’ largest lobby association representing the interests of Europe’s major retail companies (which include supermarket giants Carrefour, Lidl, Tesco, Delhaize, and Ikea). On the basis of this, concluded EuroCommerce, "[social and environmental impact reporting] should remain voluntary as well" – a position that has been echoed by fellow industry lobby groups.

For example, according to the Confederation of German Industry, the BDA, "[c]ompanies can have very good reasons for declining to report [non-financial data]", although no indication as to what these reasons might be are provided in the BDA’s submission.

The carrot not the stick

In opposing the Commission’s proposal, industry has repeatedly warned the Commission that the introduction of mandatory social and environmental impact reporting would result in "additional administrative and financial burdens" on companies17.

As EuroCommerce reminds the Commission, "[T]he reduction of administrative burden [is] a goal that the European Commission has committed itself to."Instead, argues the Japan Business Council in Europe (JBCE), "providing companies flexibility of choice within broadly defined voluntary [NFR] options is the most viable approach which is consistent with the EU 2020’s objective of enhancing companies’ competitiveness and innovation." As such, concludes EuroChambers, the federation of European chambers of commerce, the Commission ought to favour "[c]ompetition over regulation".

This was also the argument that industry successfully deployed back in 2003 to undermine the Commission's first attempt to introduce mandatory NFR.

As the 2001 Lisbon Agenda set industrial competitiveness as the guiding objective for European Integration, thus far industry has been able to appeal to the Union’s economic aspirations as a shield against regulation.

Big business hiding behind small business

In their attempt to discourage the Commission from introducing mandatory reporting on social and environmental impacts, corporate lobby associations such as EuroCommerce and BusinessEurope argued that if mandatory reporting would be burdensome for large companies, it would prove even more so for small and medium firms (SMEs), including their own subsidiaries and sub-contractors.

According to UEAPME, the lobby association representing "the voice of SMEs in Europe", SMEs fear that the responsibility for providing the data would fall upon their shoulders, as many larger companies rely on SMEs further down the supply chain for many of their products and services. However, evidence of these burdensome financial and administrative costs has been lacking. In contrast, the European Commission reports that, "Companies/preparers from Member States where there are more extensive requirements on non-financial reporting did not report increased administrative burdens."

Moreover, according to several accountants and auditors who participated in the consultation process, "SMEs collectively had a large impact on society and the environment, if not individually, so [they] should be included [in the Commission’s proposal]."1819

The desire for SMEs to be exempt may in fact have to do more with the wishes of business to avoid exposing to public scrutiny the complex value chains tying transnational corporations and SMEs.

A pick and mix approach

As well as arguing in favour of a voluntary reporting system for social and environmental information, companies like Shell, Solvay, Carrefour and Lafarge, amongst others, argue that, because of the voluntary nature of CSR, "[c]ompanies should have the flexibility to consider which international frameworks or alternative indicators are most appropriate for their business" (Shell’s submission) – or rather, companies should be free to choose what information to disclose and which to leave out.

The controversial oil giant Shell in particular reassures the Commission that its sustainability reporting is in accordance with international voluntary standards including:

[D]etailed information about our work to reduce greenhouse gas emissions, improve energy efficiency of our operations, reduce use of fresh water through recycling and advanced technologies, our efforts to engage local communities, and how we continue to build our safety culture.

When we compare this to what organisations campaigning for corporate accountability say is a minimum (see above), it is clear that the scope of current reporting mechanisms is extremely limited.

In summary the diversity of standards available to companies is the perfect tool for manipulation, public relations, and cherry picking of the data companies are willing to disclose20.

The reluctance of industry to go beyond current voluntary mechanisms is highlighted by many companies’ opposition to including, for instance, information on human rights abuses or corruption – questions that the Belgian chemical company Solvay, for instance, felt not only "would not be recommendable", but that "should be left to NGOs" to deal with21.

'Don't blame us for the crisis'

As the following statement by BusinessEurope illustrates, industry appears not to deny the need to address the (ir)responsibility of some companies’ behaviour. What it questions, however, is the need for mandatory reporting of non-financial information,

In the wake of the financial and economic crisis, voices are raised against irresponsible behaviour, lack of transparency or insufficient regulation. Due to the systemic nature of the financial crisis, adequate transparency and improved standards are crucial to restore confidence and stability in the financial sector. However, this should not be confused with introducing CSR regulation as a preventive measure to generate more responsible companies. On the contrary, this could prove counterproductive and other methods should be explored22.

Singling out the financial sector as the only culprit of the current global financial crisis has been a key strategy of neoliberal discourse.23 By relieving the rest of the business community from any responsibility, BusinessEurope argues that the appropriate solution lies not in regulation, but in developing the right set of market incentives necessary to encourage more responsible behaviour from companies.

BusinessEurope’s ideological opposition to public authorities’ intervention in the market is best expressed in a letter addressed to the Employment Committee of the European Commission, in which it makes the it clear that, "[W]e do not agree … with the use of regulation in this field or that public authorities should have a regulatory role."24

People and planet on a par with profit?

To appreciate the adamance with which BusinessEurope argues industry’s case, it is necessary to reflect on the consequences that a comprehensive and mandatory reporting mechanism for social and environmental impacts would have on companies. For this could expose the negative implications of a company’s operations by opening up global value chains to public scrutiny.

Moreover a mandatory approach to reporting on social and environmental data would put non-financial reporting de facto on a par with financial reporting. This would imply, tacitly if not formally, that the social and environmental implications of a company’s operations would be as important as the financial returns of those same operations. Profit and capital accumulation would no longer be the sole motivation of industry. Instead, its responsibility vis-à-vis society and the environment, would be seen as integral elements of industry’s raison d’être. As such, shareholder’s profits might need to be weighed against stakeholders’ interests, and not vice versa.

What is at stake here could be the redefinition of European social relations – relations between business, regulators and citizens – that have so far been structured (at least since the signing of the Maastricht Treaty) in line with a neoliberal vision of Europe’s project of integration.25 The possibility of redefining business-societal relations in ways that would curtail the freedom of the market would represent, as discussed earlier, a major cultural shift for industry.

German industry and government combine forces

The corporate campaign against mandatory non-financial reporting has had substantial support from the German Government. Industry’s position – and that of BusinessEurope in particular – became far more aggressive once the German government begun exerting pressure on the Commission to reconsider the scope of its proposal.26

According to EU insiders, Germany’s reaction to the Commission’s proposal was described "virulent" and "out of proportion".27 Despite the fact that Germany’s post-war neoliberal tradition is renowned for its dislike of government intervention in the market, however, Merkel’s pro-industry position on the question of non-financial reporting has been met with some criticism within the German Parliament28.

As part of CEO's access to documents requests, it asked to see all the communication exchanged between the Commission and the German Government over the question of non-financial reporting. These show that, in a letter sent in October 2011 by the German Secretary of State for SMEs Ernst Burgbacher to European Commissioner for Industry and Enterprise Antonio Tajani, he expresses concern about the burdensome costs of reporting requirements, and stresses that CSR should remain voluntary for all companies.29 In a response in November 2011, Commissioner Tajani reassures him that CSR will remain voluntary and that the Commission will safeguard competitiveness and the interests of SMEs. "In this sense we look forward to a continued close cooperation with German companies," writes Tajani30. Similarly a letter from the German Federal Ministry of Economics and Technology addressed to Tajani German government reminds the Commission of its "promise" to exclude SMEs from any reporting requirements.31

The fact the Commission should make promises like this raises serious questions about EU decision-making. The Commission’s own 2001 White Paper on Good Governance sets out precise rules and procedures for the Commission to follow with a view to ensuring that policy outcomes are not the result of partisanship.

Similarly, German Government Minister Ursula von der Leyen wrote to Commissioner Tajani, stating that her "government explicitly rejects mandatory reporting requirements for social and environmental information", because such obligations would lead to "considerable bureaucracy costs" for German companies32.

The BDA, the confederation of German industry, has been especially resistant of regulatory approaches aimed at changing industry’s behaviour and, according to industry insiders, has been demanding the Commission rescind its CSR agenda – a demand that the German Government appears to have been happy to push in Brussels33.

Following the Commission’s redefinition of the tone and terms of CSR policy, it would seem that the German government wrote to the Commission to express its dissatisfaction with the suggested changes. Shortly after, Pedro Ortún Silván and Thomas Dodd, the Commission officials responsible for overseeing the CSR file within the Commission, and who played a key role also in guiding the Commission’s proposal on non-financial reporting, were relieved from the brief.34

Interestingly, this is identical to what happened back in 2003. When, in 2003, the Commission attempted to introduce an initial legislative proposal for the mandatory reporting of non-financial information, Dominique Bé, the Commission official in charge of overseeing CSR policy, was suddenly relieved of his file35. The result was the weak reporting requirements introduced in the Accounting Directives that the current legislative proposal is supposed to address and remedy.

Exposing ‘Global Value Chains’

Many of the social and environmental impacts of transnational corporations (TNCs) take place outside of the EU, particularly in third countries (many of which are developing countries), where social and environmental regulations are lax or non-existent36. Here, many SMEs operate as subsidiaries or subcontractors of large multinationals, and it is through the global value chains that tie them to their parent TNCs that goods and raw materials are able to flow from the Global South to the North.

Within the current system of international trade and free markets, the competitiveness of industry, as well as that of countries, has come to depend on these global value chains. However, the general sourcing of cheap labour involved in the extraction of raw materials, and the environmental destruction associated with it, have attracted much criticism.

Example: keeping dirty laundry privateIn a recent report by Friends of the Earth, Mining for Smartphones: The True Cost of Tin (2012), the environmental organisation claims that the tin used in some of the best-selling brands of smartphones is linked to the devastation of forests, farmland, coral reefs and communities in Indonesia. Moreover, according to FoE’s report, in the Bangka mine in Indonesia, one of the largest tin mines in the world, more than sixty miners have died just in 2011, either buried underground or trapped underwater37. By allowing SMEs that supply them to avoid reporting regulations, companies can wash their hands of their impacts further down the chain, but upon which their business model absolutely depends. |

With many corporate sectors (manufacturing especially) heavily reliant on the extractive industry for the supply of raw materials, it is understandable that business is wary of the dangers inherent in reporting its social and environmental impacts – which are likely to be significant – if it obliges companies to expose the global value chains they operate through.

This not only explains why larger companies have also demanded reporting exemptions for SMEs – in order to avoid scrutiny of controversial aspects of their global supply chains – but, with manufacturing dominating the German economy, it is possible to appreciate why German industry and government in particular have been so opposed to the Commission’s proposal38.

Advisors in the dark

The pressure that industry placed on the Commission is clear in the outcome of the ‘Expert Group’ advising it on non-financial reporting. As part of its impact assessment, the Commission set up in 2011 an ad hoc group of advisors – predominantly stakeholders and other interest groups, many of them business representatives. For example, industry lobbyists BusinessEurope and UEAPME were in the Expert Group preparing the Commission's proposal39. As CEO has documented, Expert Groups weighted with corporate representatives have become a significant and somewhat infamous feature of EU policy-making40.

The Expert Group on social and environmental impacts reporting convened only three times and was not required either to reach a consensus, nor to draft a final report in which participants' opinions would be recorded. Instead, members of the group were asked by the Commission to reflect on a number of specific questions the Commission put to them ahead of every meeting. These were then debated during three brief encounters before the Expert Group was dissolved with no notice given41. According to one participant, the process felt "rather untransparent", as the Commission apparently failed to provided those in the group with any guidance during the process, or with any feedback on their input.

A closer look at the minutes of the Expert Group’s meetings, and the list of questions presented, shows evidence of the progressive realignment of the scope of the Commission’s initiative with industry’s preferences.

Selective deafness to expert advice

As the meetings progressed, the focus of the Expert Group began to narrow42.This would be understandable if agreement was progressing towards a common understanding, but there is no evidence that this was so. Rather, in the first meeting the Commission explored whether its proposal should be based on general principles (industry’s preference) or specific key indicators (NGOs' preference); by the second meeting the idea of key indicators had been side-lined.

The discussion then narrowed even further, industry preferring a focus on existing international standards that companies could pick and choose rather than predefined principles. Thus by the third and final meeting, the assumption was that the proposal would be a principle-based reporting mechanism allowing companies to comply with whichever international standard suits them best. Questions remained about whether such a reporting mechanism ought to apply to all companies irrespective of their size, or only TNCs, and whether it should include any monitoring provisions.

Nowhere in the minutes does the Commission explain the reasons for this dramatic narrowing of focus, nor does it explain the subsequent limiting of policy options. Instead, it implies that the questions put to the participants are shaped by their very own preferences.

While they were certainly the preferences of some, it is not possible from the minutes to specify whose, nor determine whether they were a majority, or even a considerable minority. The Commission states that,

Several experts supported the idea of a principles-based approach, rather than a detailed, rules-based one …A number of existing frameworks were mentioned as possible references, including the UN Global Compact, ISO 26000 or the Global Reporting Initiative (GRI) …[S]ome experts considered that using key performance indicators (KPIs) was not appropriate … Several experts highlighted that any undue administrative burden should be avoided …[emphasis added]43.

Even when the Commission reports that, "[a]nother expert suggested that companies should also be required to disclose their corporate structure, potential risks or human rights violations in their supply chain and any steps taken by the company to deal with such issues", it adds, "some other participants argued that any predefined list of topics would not represent an appropriate solution, as it would not leave enough flexibility for companies and could undermine the quality of the reports."

How it then balanced these views out and how it came to judge one position as more valid than another remains unclear. But irrespective of its methodology, the Commission appears to have progressively re-aligned its Expert Group's advice with industry’s preference. The end result is a legislative proposal that reads like the most conservative of corporate wish lists.

Watered down to nothing

The Commission’s text shows the extent to which pressure must have been exerted to downscale the scope of its proposal. The Commission states that "[a] number of options have been considered to improve the current situation, including strengthening the existing requirement, introducing new requirements for detailed reporting, or setting up an EU Standard." Alas, it explains, "[i]n light of the assessment of these policy options, it appeared that the preferred option would be strengthening the existing obligation, by requiring a non-financial statement within the Annual Report" – the weakest of the policy options.

To this end, the Commission’s proposal suggests the modest objective:

To increase the transparency of certain companies, and to increase the relevance, consistency, and comparability of the non-financial information currently disclosed, by strengthening and clarifying the existing requirements [emphasis added].

What this entails in practice remains unclear due to the highly ambiguous language of the legal text proposed.

By nature, directives leave room for interpretation as a way of favouring implementation within existing national legal frameworks. The danger, however, is that the ambiguity of the directive will lead to major differences between Member States’ interpretation – the very reason the Commission decided to undertake a review of the 2003 Accounting Directives in the first place (see above).

The likely consequence of this ambiguity will be that industry’s lobbying activity will shift to the national level to shape the ways in which Member States will implement the directive within national legal frameworks.

If this suggests little improvement on the existing legislation addressing the disclosure of social and environmental impacts, so do the various provisions the proposal puts forward. This includes requiring "certain large companies" to disclose a "statement" in their Annual Report on information relating to at least environmental, social, and employee-related matters, respect of human rights, anti-corruption and bribery aspects. In providing this information, companies "will rely on internationally-accepted frameworks". Companies that choose not to do so "will be required to explain why this is the case".

The Commission explains that "[t]he measure takes care to avoid unnecessary administrative burden on companies operating in the Single Market, and, in particular, on the smallest ones, which are subject to no new disclosure requirements." Thus in line with the industry agenda, SMEs are exempt, as are subsidiaries44.

The choice of the Commission to review its own definition of what constitutes a large company is yet another consequence of pressure exerted from the German government. German Minister for Labour and Social Affairs Ursula von der Leyen, argued that because many companies in Germany are considered small and medium enterprises (because of their family-owned structures) despite having more than 250 staff members, the Commission should find ways of ensuring that they too were exempted from the proposal45.

Thus Commission’s revised definition of what would constitute a ‘large’ company up to one with over 500 employees appears to be the direct consequence of these German interests.

As a result of this kind of pressure, breaking down the proposal, it becomes unclear whether the proposal will affect a statistically significant number of companies at all. The text states that,

[T]he obligation will only apply to those companies whose average number of employees exceeds 500, and exceeds either a balance sheet total of 20 million euros or a net turnover of 40 million euros.

Moreover, as specified in Article 1 (c), those companies that prepare a report corresponding to the same financial year shall be exempted from the obligation to provide the non-financial statement, provided that the report: (i) covers the same topics and content required by Article 1 (a), (ii) relies on international frameworks, and (iii) is annexed to the Annual Report.

The Commission states that SMEs make up 99 percent all off European enterprises46. If these are excluded from reporting, then a mere one percent of European industry will be obliged to report data on the social and environmental impacts of their operations.

According to the Commission about 42,000 large companies make up this one percent of European enterprises, that is, companies with a staff exceeding 250 members. The new reporting requirements, however, will only affect companies with more than 500 staff members and €20m revenue. According to an official within DG MARKT, the companies affected would then be further reduced to just 18,000.

Since the proposal will moreover exempt those companies that already produce non-financial reports (which according to the Commission are about 2,500), whilst also allowing to opt out all together from reporting, it is unclear what, if any impact this new piece of legislation will have on improving corporate transparency and accountability as it would affect a mere 0.3 percent of all companies in the EU.

Whilst on the one hand the lack of substance of the current text appears to reflect the wish of industry to ensure that the Commission’s review of the Union’s CSR policies would be essentially meaningless, it also indicates the massive influence that German interests play in shaping EU policy decisions.

Will the European Parliament stand up to Germany Inc.?

After the European Commission proposal had been watered down to satisfy the demands from the German government and industry lobbies, it was stalled for several months. The main reason was that another important piece of CSR legislation, on EU transparency rules for extractive industries, was stuck because of conflicts between MEPs and governments. There were fears that this delay could have gone on for much longer, but then there was a sudden breakthrough, and the extractive industries rules were approved in the European Parliament in mid-April 2013. This paved the way for the Commission's proposal on non-financial reporting to be released on 16 April 2013.

Unfortunately the proposal fails to secure any meaningful progress in reporting requirements that enable scrutiny and thereby greater accountability. The way the proposal was progressively weakened exposes the absurd degree to which the current German government aligns itself with corporate interests – and the power of Germany Inc in EU decision-making.

The proposal will now be discussed in the European Parliament. MEPs have the opportunity to patch the many loopholes in the proposal, starting with ensuring that transparency obligations will cover all companies, including subcontractors. The coming months will show whether MEPs are able to act on behalf of corporate accountability and stand up to big business lobbying.

Download this report as pdf here. Picture: Glenn Hurowitz

- 1. See European Commission’s webpage on non-financial reporting for a general overview of the policy process: http://ec.europa.eu/internal_market/accounting/non-financial_reporting/i...

- 2. See for instance the 2008 report by Professor Ruggie to the UN Human Rights Council: ‘Protect, Respect and Remedy: a Framework for Business and Human Rights’. Available at http://www.reports-and-materials.org/Ruggie-report-7-Apr-2008.pdf

- 3. Op cit.

- 4. The Single Market Act supports "promot[ion of] the development of businesses which have chosen – above and beyond the legitimate quest for financial gain – to pursue objectives of general interest or relating to social, ethical or environmental development. In order to ensure a level playing field, the Commission will present a legislative proposal on the transparency of the social and environmental information provided by companies in all sectors." Single Market Act, SEC(2011)467

- 5. Fourth Council Directive 78/660/EEC, 25 July 1978. p. 11–31. According to art.46(1)(b), "to the extent necessary for an understanding of the company's development, performance or position, the analysis shall include both financial and, where appropriate, non-financial key performance indicators relevant to the particular business, including information relating to environmental and employee matters".

- 6. ECCJ, ‘Position Paper on Non-Financial Reporting by Companies’, May 2012, http://www.corporatejustice.org/Greater-corporate-transparency-at.html?l...

- 7. See for instance: the UK Accounting Standards Board (ASB) (2009). ‘Rising to the challenge. A review of narrative reporting by UK listed companies’. London; and The Guardian review of the Black Sun report at http://www.guardian.co.uk/sustainable-business/risk-ftse100-companies-an...

- 8. http://ec.europa.eu/enterprise/policies/sustainable-business/corporate-s...

- 9. http://ec.europa.eu/enterprise/policies/sustainable-business/corporate-s...

- 10. http://ec.europa.eu/enterprise/policies/sustainable-business/corporate-s...

- 11. Ibid.

- 12. http://ec.europa.eu/internal_market/consultations/docs/2010/non-financia...

- 13. http://ec.europa.eu/internal_market/consultations/docs/2010/non-financia...

- 14. https://circabc.europa.eu/faces/jsp/extension/wai/navigation/container.jsp

- 15. According to the consultation’s summary report, industry’s submissions were about half of the contributions, with the remainder split amongst NGOs, accountants and auditors, public authorities and standard setting bodies. Whereas industry praised the initiative as an effort to bring all companies operating within the EU on a level-playing field, NGOs highlighted the benefits it would bring in terms of the improved comparability between companies operating in different countries and sectors (op. cit.).

- 16. Unless otherwise specified, all industry quotes have been extracted from the various companies and industry lobby associations’ positions submitted to the European Commission’s public consultation. These can be accessed at: https://circabc.europa.eu/faces/jsp/extension/wai/navigation/container.jsp

- 17. EuroChambers, the lobby group representing the interests of Europe’s national chambers of commerce "rejects a mandatory disclosure" on the basis that, "[o]bligatory standards limit the freedom of companies, raise costs and the bureaucratic burdens and make CSR unattractive". EuroChamber’s submission at: https://circabc.europa.eu/faces/jsp/extension/wai/navigation/container.jsp

- 18. European Commission’s Summary Report of the consultation: http://ec.europa.eu/internal_market/consultations/docs/2010/non-financia...

- 19. The Centre for Strategy and Evaluation Services (CSES) – a UK spin-off of the global service firm Ernst & Young – was commissioned by DG MARKT to conduct a study aimed at "providing some qualitative analysis of current reporting practices in the EU … and at providing a cost/benefit analysis of non-financial reporting by companies".

- 20. International instruments vary widely, as most of them are normative standards or operational guidelines (ISO 26000). Moreover, some are public norms, where others are private, which brings into question the legitimacy and applicability of these standards. The only existing reporting tool, the Global Reporting Initiative (GRI), is a private norm with no mandatory guidelines and allows companies to pursue a "comply or explain" approach. Recent research into companies producing GRI reports appears to show that companies are massively over-claiming their GRI compliance: e.g. according to research by Vienna University, only 11% of companies actually met the full terms of publishing top workplace indicators as opposed to 86% who declared they had. For human rights indicators, 62% of companies declared compliance with top indicators, but only 20% really met the terms (http://csr-reporting.blogspot.de/2012/11/false-claims-in-sustainability-...). The voluntary nature of all these mechanisms also means that a lack of compliance with the norms is not followed by any civil, criminal or social consequences.

- 21. Companies that in their submissions also opposed disclosure of human rights information include Bayer, Siemens, and Unilever amongst many others.

- 22. BusinessEurope. ‘European Business Supports Transparency’. 18 September 2009. This position echoes BusinessEurope’s wider view: the EU "should not interfere with companies seeking flexibility to develop an approach to CSR according to the specific needs of their stakeholder and their individual circumstances". Thus, an "interventionist approach is not the right way forward". (BusinessEurope, 2012: p.1, p. 4)

- 23. See for instance The Financial Times’ series on ‘The Future of Capitalism’ from 2009: http://www.ft.com/indepth/capitalism-future

- 24. Letter from the Director General of BusinessEurope to members of the Employment Committee of the European Parliament dated 7th January 2012.

- 25. See for instance the pioneering work by Van Appeldoorn, B (2000). Transnational Class Agency and European Governance: The Case of the European Round Table of Industrialists. New Political Economy. Volume 5, Issue 2; Cafruny, A. and Ryner, J (2003). A ruined fortress? Neoliberal hegemony and transformation in Europe. Rowman & Littlefield.

- 26. See, for instance, Kinderman, D. (2013). Corporate Social Responsibility in the EU, 1993-2013: Institutional Ambiguity, Economic Crises, Business Legitimacy, and Bureaucratic Politics. Journal of Common Market Studies Vol. 51 No. 3.

- 27. Ibid.

- 28. The three opposition parties have been in favour of disclosure of non-financial information.

- 29. Letter to Commissioner Tajani from Ernst Burgbacher of the German Ministry of Economy and Science, 24 October 2011.

- 30. Letter by Commissioner Tajani to Ernst Burgbacher of the German Ministry of Economy and Science, 17 November 2011.

- 31. Letter to Commissioner Tajiani from Ernst Burgbacher of the German Ministry of Economy and Science, 24th October 2011

- 32. Letter to Commissioner Tajani from Ursula von der Leyen, German Ministry for Labour and Social Affairs, November 24 2011.

- 33. Personal communication with Dr. Kinderman.

- 34. Mr Ortun and Mr Dodd have refused to comment on the matter.

- 35. See Kinderman, D. (2013). Corporate Social Responsibility in the EU, 1993-2013: Institutional Ambiguity, Economic Crises, Business Legitimacy, and Bureaucratic Politics. Journal of Common Market Studies Vol. 51 No. 3.

- 36. See, for instance, the following reports: Time for Transparency http://www.corporatejustice.org/Time-for-Transparency.html?lang=en ; Spilling the Beans http://www.corporatejustice.org/Spilling-the-Beans.html?lang=en ; The Toxic Truth http://www.corporatejustice.org/Report-slams-failure-to-prevent.html?lan... ; Where the Shoe Pinches http://www.corporatejustice.org/IMG/pdf/summary_somo_report_child_labour... ; Fatal Fashion http://somo.nl/publications-en/Publication_3943/

- 37. To read the full report: http://www.foe.co.uk/resource/reports/tin_mining.pdf

- 38. Germany's manufacturing sector is responsible for 23 percent of the country's GDP, compared with just 10 percent in France and Great Britain (ref - Cologne Institute for Economic Research).

- 39. Letter from Commissioner Tajani to Ursula von der Leyen, German Ministry for Labour and Social Affairs, January 11 2012.

- 40. Whereas some Expert Groups may be established by a formal Commission’s decision or legal act, others can be established informally on an ad hoc basis by individual DGs. At the same time, either can run on a temporary or semi-permanent basis, depending on the policy issue to be advised on (Gornitzka and Sverdrup 2008).

- 41. All minutes available under the heading ‘Impact Assessment for new legislative proposal’ on the Commission’s website: http://ec.europa.eu/enterprise/policies/sustainable-business/corporate-s...

- 42. Ibid.

- 43. Quotes extracted from the Commission’s minutes of the Expert Group’s meetings. Ibid. For non-native English speakers it is worth pointing out that, according to the Oxford English Dictionary, ‘several’ means: ‘more than two, but not many’.

- 44. "Provided that the exempted company and its subsidiaries are consolidated in annual report of another company, and that consolidated annual report fulfils the requirements set out under Article 1 (a)".

- 45. Letter to Commissioner Tajani from Ursula von der Leyen, Op cit.

- 46. http://ec.europa.eu/enterprise/policies/sme/ ; http://ec.europa.eu/enterprise/policies/sme/facts-figures-analysis/index...