Not our Europe

The ‘agreement’ that the eurozone countries and the Troika forced on the Greek government during the “night of shame” strangled space for a progressive project. It is not only dangerous for the Greeks, but for citizens all across the European Union.

There are many regrettable outcomes of the ‘agreement’ forced on the Greek Government during the longest ever Euro Summit on 12-13 July 2015, or the European Union’s “night of shame”. On top of harsh austerity measures and further attacks on social rights, a promising alternative has lost tremendous ground. In the Brussels institutions, there is a sigh of relief, as the first real obstacle to the strand of undemocratic, neoliberal European integration in response to the eurocrisis since 2010, has now been removed. It was not only the Greeks that lost out, but all Europeans looking for alternatives to austerity that make better economic and social sense.

As progressive forces across Europe are now considering next steps, one aspect should be highlighted: the anti-democratic nature of European Monetary Union (EMU) – with the actions of the European Central Bank and the eurogroup (the national finance ministers of the eurozone) as key examples – and the fact that this has become the cornerstone of European integration. That night, the eurozone countries and the Troika were not merely being cheap on money, they were acting on behalf of a European Union that leaves no space for a progressive project.

Our co-operation?

Ahead of final phase of the negotiations on an ‘agreement’ between the Eurogroup, the Troika, and the Greek Government, German Chancellor Merkel said it would have to be ensured “that the advantages are greater than the drawbacks for the future of Greece, as well as for the Eurozone and the principles of our cooperation.” The negotiations finished with full submission of the Greek Government to the demands of its creditors. The creditors forced their will by squeezing the liquidity of Greek banks, and ultimately by threatening Greece with expulsion from the Eurozone.

While Merkel’s claim that this episode will strengthen the principles of economic and monetary cooperation may seem out of place, given how Greece was coerced into ‘co-operation’, her words are in fact straight to the point. That night a key battle in the fight for Europe took place. With the weight of a unified, determined European political and economic elite, an ever growing EU rule book on the ‘correct’ economic policy, and the manifest power of the euro-construction all pitted against a small country in a deep economic crisis, the result was a given.

Their Europe

Confronted with excessive force, the Greek Government suffered total humiliation: a week after winning overwhelming popular support for rejecting the creditors’ harsh austerity demands, it had to swallow even harsher demands in order to prevent the immediate collapse of Greek banks and to open the door for negotiations on a new loan package, a third memorandum. These negotiations hold no promise to alleviate the crisis in Greece. Even if the next memorandum did include debt relief for Greece, it is widely predicted that any deal would be conditional upon further austerity and the roll-back of social rights.

The determined use of sanctions and threats against the Greek Government should come as no surprise to those who have followed the response of the European Union to the eurocrisis, whichhad its roots in the financial crisis and the divergence created by the common currency – with winners and losers. Yet it was immediately spun as a blow created by lavish public spending, overly generous social welfare, and ineffective labour markets. The road to a full-frontal attack on welfare and labour rights across Europe was paved by the concerted efforts of governments, the mass media and big business lobbies.

Exploiting the crisis

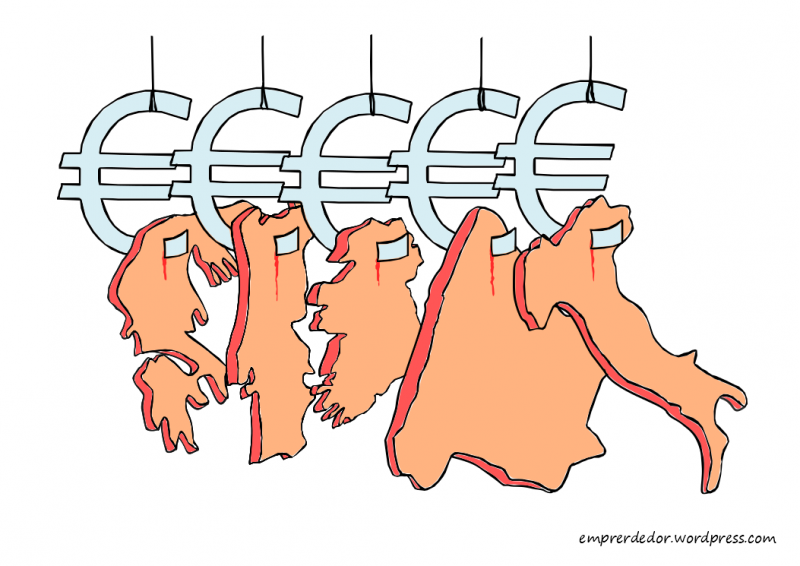

For five years now, attempts to strengthen the Economic and Monetary Union have focused on creating a web of bureaucratic rules and mechanisms to force austerity policies and to attack social rights. The Troika (officials from the European Commission, the European Central Bank, and the International Monetary Fund tasked to force austerity and neoliberal reforms onto Greece, Ireland, Portugal, and Cyprus in return for new loans to service outstanding debt) is but one of the new tools that were created. This was always the EUtopia of big business groups and their neoliberal allies in the EU institutions, who saw opportunities in the crisis. This explains their refusal to acknowledge the complete failure of the EU-driven austerity policies. Even the dramatic contraction of the Greek economy of a full 25 per cent since 2008 during brutal austerity measures never made the protagonists think twice.

During a Brussels conference in January 2011, former EU Commissioner Mario Monti summarised the thinking in these circles by enthusiastically welcoming the first major steps towards stronger EU ‘economic governance’: he said, “Thank you, Greek crisis”.1 At that time Monti was advising the European Commission on the future of the EU Single Market, as well as serving on the Board of International Advisors of Goldman Sachs. In November 2011 he would be catapulted into power as unelected Prime Minister of Italy, after the ECB effectively toppled the Berlusconi Government, in order to implement austerity and reforms as demanded by the EU institutions.

Monti’s gratitude and that of the rest of the political and economic EU elite would not be disturbed by the collapse of the Greek economy that unfolded at the time, quite the contrary. In September 2011, he expressed awe at the achievements of the common currency: “Today we are witnessing – and it is not a paradox – the great success of the euro and the most concrete manifestation of this success is Greece, and forced to give value to the culture of stability which is transforming itself.” Monti chose his words with care: “giving value to the culture of stability” sounds much nicer and more civilized than “imposing harsh austerity and neoliberal reforms”.

The euro as a political weapon

But Monti's blessing was a curse for the Greeks. Already in February this year, in response to the left wing victory in Greece's January elections, the European Central Bank had made it more difficult for Greek banks to get credit – a move it did not make under the previous government under similar circumstances. This showed how the ECB, theoretically a neutral actor, was making highly political moves. In the end, the ECB capped emergency liquidity, forcing the Greek Government to cut access to money, and made the clock tick towards a euro exit. With empty banks, there would be no escape from introduction of a new currency, and as the Greek Government had made no preparations whatsoever2, the result could only be chaos.

For all of the EU, the euro has become the main engine for integration, and one that is both authoritarian and neoliberal.

A sigh of relief from business

A Greek exit could have thrown this “neoliberal integration by currency” into doubt. For that reason, big business lobby groups were biting their nails in the course of the negotiations. They feared Greece would win exceptions at the negotiating table that could halt the sweeping pro-business reforms set in motion by the crisis – and maybe set precedents for other eurozone countries. In a statement issued on 8 July, a few days before the agreement was made, BusinessEurope urged that the Greek Government come up “with credible, precise proposals for growth enhancing structural reforms”. And as so often before, the group argued that the “outcome of this crisis should be a strengthened Economic and Monetary Union”.

On the day of the deal, BusinessEurope was quick to respond with yet another call for a “stronger Economic and Monetary Union and improved governance and convergence in the European Monetary Union.”

Not our Europe

The result so far of the Greek rebellion against the neoliberal diktats, are utterly timid, if not outright depressing. With no plan B, the Syriza Government was an easy victim. For the architects of a neoliberal European Union, this could provide new impetus for ‘their Europe’. Already, the “five presidents”, that is, Juncker of the European Commission, Tusk of the EU Council, Schulz of the European Parliament, Draghi of the European Central Bank, and Dijsselbloem of the eurogroup – all of whom were part of the attack on Greece – have tabled a master plan for the next steps, and they are likely to discover new opportunities for an expanded neoliberal project.

This poses a fresh challenge to social movements and other progressive forces across Europe. The task is not just to act in solidarity with the Greeks fighting against austerity and for social rights, but to fight a flawed model of undemocratic, neoliberal European integration as a whole. While the “night of shame” that humiliated Greece was a powerful blow to progressive forces, to resist the closing down of democratic spaces and economic alternatives on the continent will require concerted pan-European citizen action.

- 1. Corporate EUtopia; How new economic governance measures challenge democracy, Corporate Europe Observatory, January 2011.

- 2. Former Greek Finance Minister Yanis Varoufakis claims he had a plan B that Tspiras wouldn’t accept.