Regulating finance: a necessary but 'up-Hill' battle

Newly-released documents show that as far as financial regulation is concerned, lobbyists are besieging the Commission – which has an open door policy towards them. Differing opinions on the subject rarely make it through. The outgoing Commissioner never made good on commitments to transparency and safeguards against corporate capture. Can the new Commission fare better? And why is its prospective commissioner responsible for this area, Jonathan Hill, a former lobbyist?

In July, after a tug-of-war spanning months, the Directorate General of the Single Market Commissioner released a list of meetings the civil servants had held with industry representatives since early 2013. With about 400 meetings in the preceding year and a half before mid 2014, that translates to at least one meeting per working day with either a bank, an association of banks, or an investment fund. This is a very high frequency, perhaps it could even be described as a state of siege, except that those besieged appear to be rather welcoming. When it comes to finance, the Commission seem to make no distinction between advisor and lobbyist. This is a culture seemingly deaf to efforts to rein in financial markets.

The newly released list of meetings underlines the need for change in the relationship between the Commission and its civil servants on the one hand and the financial lobby on the other. It reflects a need to ensure that the Commission adopts rules on transparency and rules to keep corporate capture at bay. While there have been interesting statements from the next Commission President Juncker regarding this recently, it will not happen without public pressure.

Intensive door-knocking

Corporate Europe Observatory started asking the Commission for lists of meetings between DG MARKT (the directorate responsible for regulating finance) and industry representatives back in April 2014, off the back of the release of a report that showed a minimum of 1700 people working as EU lobbyists for the financial sector. This led to a freedom of information request for a full list of finance lobby meetings held, including minutes, from late 2013 to date. However DG MARKT, the office responsible for such requests, balked at the idea, considering the request “excessively broad” and refused to respond in that form. As a compromise, it was agreed to narrow down the request to the offices responsible for financial services.

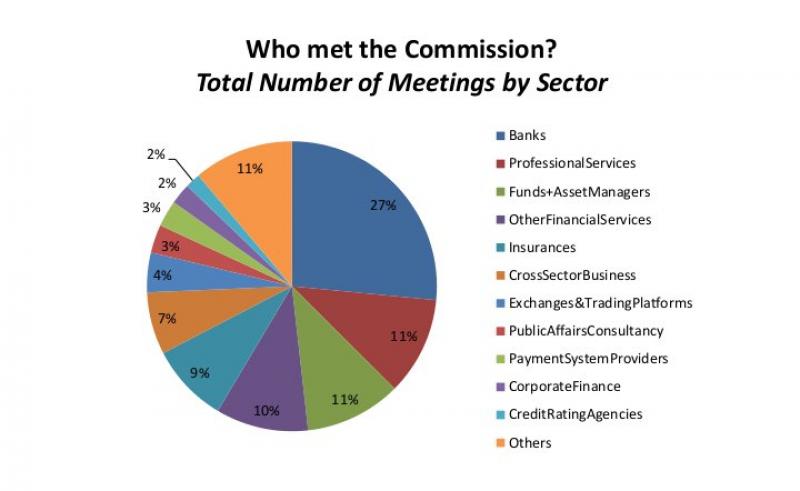

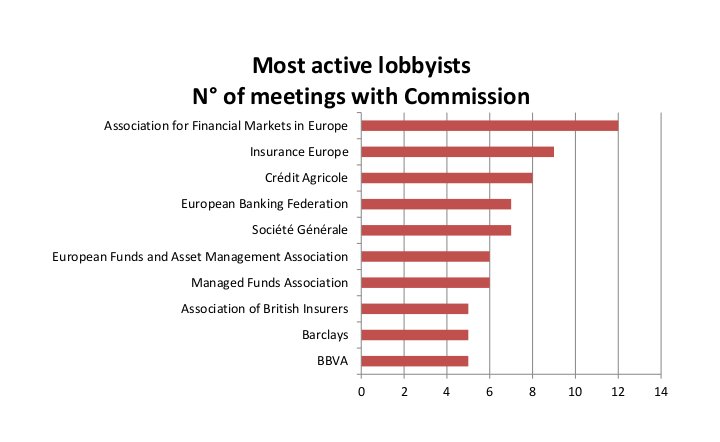

The list of meetings released three months later provides interesting information on the financial lobby. For a start, there is the sheer number of meetings with more than 400 listed. And there are interesting details as well. For instance, the investment funds, the biggest banks, and the national banking associations all seem to meet with DG MARKT at least four times a year. The biggest lobbying associations, such as the mega-bank grouping the Association for Financial Markets in Europe (AFME) and hedge fund and private equity fund organisation European Fund and Asset Management Association EFAMA, boast eleven and six meetings, respectively. In terms of type of institution that lobbies most, the banks are the undisputed number one, with 27 per cent of the meetings.

The list of meetings released three months later provides interesting information on the financial lobby. For a start, there is the sheer number of meetings with more than 400 listed. And there are interesting details as well. For instance, the investment funds, the biggest banks, and the national banking associations all seem to meet with DG MARKT at least four times a year. The biggest lobbying associations, such as the mega-bank grouping the Association for Financial Markets in Europe (AFME) and hedge fund and private equity fund organisation European Fund and Asset Management Association EFAMA, boast eleven and six meetings, respectively. In terms of type of institution that lobbies most, the banks are the undisputed number one, with 27 per cent of the meetings.

As for whether a lobby group is registered, the Commission is not picky. Almost half of the delegations represented entities that are not in the EU’s Transparency Register, which the Commission helped set up specifically to meet demands for more lobbying transparency. That seems to confirm CEO’s suspicion that the overall attitude in the Commission is that lobbyists should be free to choose whether or not they will publish the scant information necessary in the Transparency Register. A decision not to register does not seem to harm their opportunity to lobby Commission decision-makers.

As for whether a lobby group is registered, the Commission is not picky. Almost half of the delegations represented entities that are not in the EU’s Transparency Register, which the Commission helped set up specifically to meet demands for more lobbying transparency. That seems to confirm CEO’s suspicion that the overall attitude in the Commission is that lobbyists should be free to choose whether or not they will publish the scant information necessary in the Transparency Register. A decision not to register does not seem to harm their opportunity to lobby Commission decision-makers.

Barnier’s legacy

The picture left behind by the outgoing Commissioner Michel Barnier is that of a Commission captured by corporate interests. In the course of his term, Barnier did, on several occasions, show a will to deal with the problem. When being grilled by the European Parliament during his nomination hearing, he vowed to ensure broader participation in the advisory groups (expert groups) that provide input to the Commission on financial services. These are groups that had been completely dominated by the financial lobby and this was a promise he would later repeat in a letter to concerned NGOs. Also, he flirted with the idea of introducing an open calendar that would allow the public to see who the Commissioner had met with. And towards the end of his term, surprisingly, he decreed a total ban on meetings with financial lobbyists in the final phase of preparing a proposal on the reform of the EU´s banking structure. However, at the end of the day, all of this resulted in little concrete improvement. Expert groups continue to be dominated by corporate lobbyists, no extra measures on transparency have been adopted, and the ban on lobbyists meetings was called off the minute the proposal on banking structure was released. Incidentally, this proposal was much weaker than the one suggested by a team of experts appointed by the Commissioner.

Juncker’s limited transparency

So, what will a new Commission bring ?

For a start, Commission President Juncker has announced a new approach to transparency. In his letter to the Commissioner-designates, including Jonathan Hill, the prospective Commissioner for Financial Stability, Financial Services, and Capital Markets Union, Juncker writes that he foresees “a new commitment to transparency.” According to Juncker, transparency “should be a priority for the new Commission and I expect all of us to make public, on our respective webpages, all the contacts and meetings we hold with professional organisations or self-employed individuals on any matter relating to EU policy-making and implementation. It is very important to be transparent where specific interests related to the Commission’s work on legislative initiatives or financial matters are, discussed with such organisations or individuals.”

From his political guidelines to the Commissioners Juncker calls for an agreement with the Council and the Parliament on a mandatory lobby register and that in some unspecified way, the Commission should “lead by example”.

Seemingly, what this adds up to in the medium term is that the Commissioners will run an open calendar, which will allow the public to see which lobbyists they meet with. While that would be a welcome step forward, it is clearly insufficient.

The 'up-Hill' battle

This is mainly because the meetings between the Commissioner and lobbyists are only the tip of the iceberg, as clearly demonstrated by the list of meetings civil servants and lobbyists already released through a freedom of information request. As Junckers initiative does not seem to include the meetings between Commission staff and lobbyists, this very high number of meetings, highly relevant when it comes to detecting the routes of influence used by lobbyists, would remain under the radar.

This is mainly because the meetings between the Commissioner and lobbyists are only the tip of the iceberg, as clearly demonstrated by the list of meetings civil servants and lobbyists already released through a freedom of information request. As Junckers initiative does not seem to include the meetings between Commission staff and lobbyists, this very high number of meetings, highly relevant when it comes to detecting the routes of influence used by lobbyists, would remain under the radar.

So, while there might be a step forward on the horizon in terms of transparency, it would not enable citizens to follow who is putting pressure on the Commissioner’s civil servants. And in terms of the influence of the financial lobby over EU policies, there are at least three problems.

First, the new political agenda for finance set out by Juncker in the “mission statement” sent to Jonathan Hill, is one that seems to put a full stop to the reform agenda. There is no mention of new initiatives to improve regulation, and remarkably, the timid Barnier proposal on banking structure, the last big and unfinished initiative from his term, has slipped off the agenda and will not, it seems, be re-tabled. Instead, the emphasis in Juncker’s mission letter to Hill is on expanding securities markets – the very same financial instruments that set the financial meltdown in motion in 2008 – and a “capital markets union”.

Second, in all of this, the expert groups are out of the spotlight, and no promises to end the dominance of the financial lobby in the advisory structures have been made.

Third, there is the nomination of Jonathan Hill to the post as Commissioner for financial markets. Corporate Europe Observatory swiftly denounced the move as Jonathan Hill is a former lobbyist and co-founder of Quillers, a lobby consultancy with the City of London Corporation and HSBC on its list of clients.

British finance lobbyists jubilant

In the beginning, when it was announced that President Juncker would create a Commissioner for finance – hitherto a part of the single market Commissioner’s portfolio – the financial community in London were terrified. According to the Financial Times (3. August 2014), it was “widely accepted that a UK candidate would never be allowed to oversee City regulation”, and for that reason, the bankers of London feared the move would ultimately “harm the UK’s national interests”. In a comment, Anthony Browne of the British Bankers´ Association said “the UK could find itself at a disadvantage”, and stressed that he feared a new Commissioner “would want big new initiatives of their own…. The last thing we need now are big initiatives.”

The tone changed 180 degrees when Jonathan Hill was revealed as President Juncker's choice . Now, the head of the British Bankers Association greeted an appointment that would “unlock the flow of finance”. “This is a good decision for Europe. We welcome the approach by President-elect Juncker to entrust key Commission portfolios to people with the right experience”, Browne said in a statement.

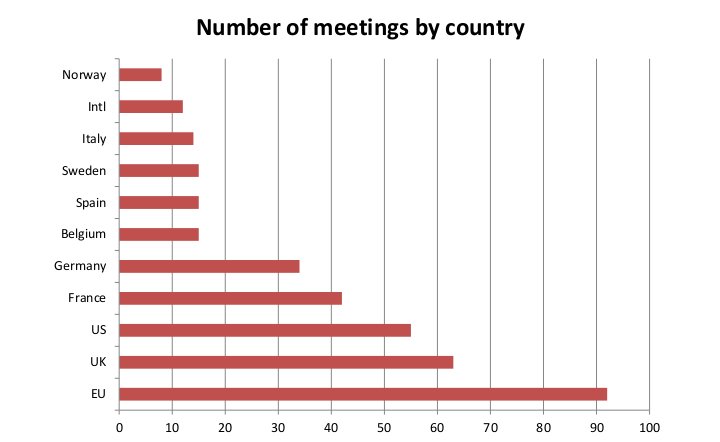

Other major lobby groups have joined the chorus, including Quillers' client the City of London Corporation, AFME, and many others. Clearly, Jonathan Hill is 'one of the boys'. It seems certain he will meet many people from the UK financial industry, and possibly even ex-colleagues from the lobbying business, as the UK boasts the most developed and strongest financial lobby community in Europe, and are the most frequent visitors at DG Markt according to the recently released lists.

Questions to Hill

In fact, Jonathan Hill should be rejected by MEPs because of his prior background as a revolving doors lobbyist and PR man. To citizens, not least the millions of Europeans that have paid a high price for the mis-adventures of financial corporations, the new Commission represents a problem. It looks like the new Commission will usher in a new era where the struggle to roll-back the power of the financial lobby and the financial sector will be an 'up-Hill' battle. But however difficult, it remains highly necessary.

Given his background, it is crucial that Jonathan Hill is confronted with questions that go to the heart of the matter. Hopefully, when the European Parliament is to assess the new Commissioner at a hearing on the 1st of October, he will have to answer the burning questions regarding corporate capture and the need for transparency, questions such as:

- whether the corporate dominance of advisory groups will continue,

- whether he will put spanner in the wheels on financial reform and pursue a liberalization agenda,

- whether he will be honest and open about his and his civil servants' interaction with financial corporations and their lobbyists.

The answers to these questions could reveal how steep the climb will be.

| No notes from meetings with lobbyists? |

| CEO's freedom of information request was for a full list of meetings with the financial industry and for minutes from these meetings. When releasing the list, the Commission refused to release minutes from the meetings, claiming that it has “a system of internal debriefing, which does not give rise to formal documents". CEO has appealed this, arguing that it is very hard to imagine that the Commission has no minutes and reports at all from these hundreds of meetings with industry. Also, it seems to be contradicted by the existence of a large number of minutes from similar meetings, obtained by CEO through freedom of information requests over the years. Besides, there is no basis in the EU's freedom of information law to distinguish between "formal documents" and other documents. |