TTIP: A lose-lose deal for food and farming

Food is on the table at the negotiations for the EU-US trade deal the Transatlantic Trade and Investment Partnership (TTIP). From a look at their lobbying demands, the agribusiness industry seems to regard the treaty as a perfect weapon to counter existing and future food regulations. However, the corporate food and agriculture agenda has not gone un-noticed. The negotiations face rough weather as more and more people on both sides of the Atlantic are understanding what we stand to lose from this agreement.

One of the main aims of TTIP is to facilitate trade by removing differences in legislation between the EU and the US. There are strong concerns that the TTIP negotiations will therefore lead to the watering down of European food safety standards, and other agriculture and food-related policies1. But TTIP could also be used to attack positive food-related initiatives in the US, particularly at the state level, such as local preference legislation (i.e. giving preference to local suppliers).

Political leaders from both the US and EU have made attempts to counter the concerns raised over the risks TTIP poses to food and farming. For example, in February the EU Trade Commissioner Karel de Gucht addressed fears that TTIP could create a 'race to the bottom' by saying: "We are not lowering standards in TTIP. Our standards on consumer protection, on the environment, on data protection and on food are not up for negotiation. There is no 'give and take' on standards in TTIP."2 Similarly, on a visit to Brussels in March US President Obama said: "I have fought my entire political career and as President to strengthen consumer protections. I have no intention of signing legislation that would weaken those protections."3

Despite these reassurances, then, in June 2014 the US Agriculture Secretary Tom Vilsack made no secret of taking the corporate agenda on board: to attack EU standards on GMOs and beef with artificial hormones, and force down the general level of standards under a false pretext that they should be based on 'sound science' – a corporate public relations term.4

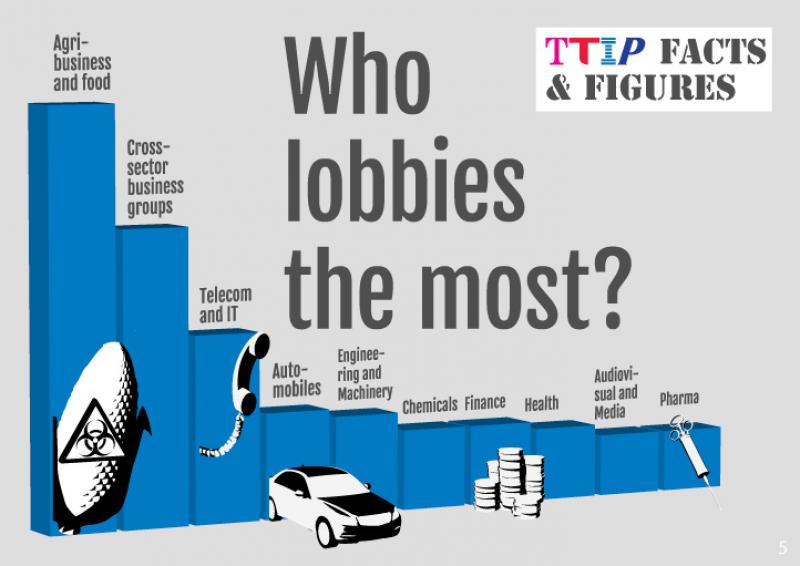

Lobbying from the agribusiness and food industry over TTIP has also been intensive on the European side. CEO's analysis of numbers of lobbying encounters between industry groups and the European Commission (only taking into account its Directorate-General for Trade, 'DG Trade'), between January 2012 and April 2013, shows that agribusiness-related lobby groups by far outnumber all other sectors.5 Not only that: DG Trade indeed has been actively chasing some of the industry lobbies for their wishlists. An email from DG Trade obtained by CEO, dated 26 October 2012, sent to the pesticide lobby group ECPA (European Crop Protection Association - BASF, Bayer Crop Science, Syngenta, Monsanto), encourages ECPA to participate in a consultation on TTIP. DG Trade writes: "A substantial contribution from your side, ideally sponsored by your US partner, would be vital to start identifying opportunities of closer cooperation and increased compatibility."6 In response, a few weeks later ECPA and CropLife America put forward their joint demands.7

What industry wants

In this article we are looking at some of the agribusiness positions, so much sought-after by the Commission. Two in particular: the set of demands put forward by ECPA and Croplife America mentioned above, and a joint position by food industry lobby group FoodDrinkEurope, with Europe's mainstream farmers' lobby, COPA-COGECA, both published in 2014.8

These two coalitions are pushing for a number of tools and principles to be enshrined in the proposed EU-US trade deal:

- They demand that policies and standards should be based on 'sound science'. In reality this means 'industry-friendly science' and a direct attack on the use of the precautionary principle.

- The 'mutual recognition' and 'harmonisation/equivalence' of standards in food and agriculture as a first step. Differences in rules between the EU and the US that are seen as 'trade-distorting' by industry would be dealt with by mutual recognition of each other's standards, or going further and harmonising them. The implementation phase of regulation provides another opportunity for standards to be attacked without changing the laws as such.

- Regulatory cooperation is the ultimate goal, with the aim to jointly review existing rules or standards that are seen as barriers to trade, and prevent new ones in the future.

Below we examine these industry demands and their impacts more closely.

How sound is 'sound science'?

While in itself far from perfect, the EU has a 'farm to fork' policy where each part of the food chain is monitored and – at least in some areas – applies the precautionary principle. The US system in contrast focuses only on the end product, which can only be regulated or banned when there is a scientific consensus on its danger or toxicity. Meanwhile, Europe's precautionary principle enables intervention without waiting for the end of the scientific debate.

From tobacco to climate change, there is a long history of industry tactics to create doubt over the scientific evidence, paying studies to maintain this doubt alive in the media and attacking any unwanted evidence as 'junk science' as opposed to 'sound science'. In a hard hitting column published in Nature, science writer Colin Macilwain says: "The term 'sound science' has become Orwellian double-speak for various forms of pro-business spin."9

This is just as true in food regulation. With TTIP, industry is taking its fake notion of 'sound science' to stage an ongoing attack on the EU food safety system, implying that it is not science-based. ECPA and CropLife for instance attack the EU pesticide risk assessment, demanding "the inclusion of science-based risk assessment as the unified basis for pesticide regulation".10 Indeed, US-negotiators are already pushing strongly for a separate article on “science-based risk assessment” in TTIP.11

In fact, while industry claims that current EU risk assessments are more demanding than is scientifically legitimate, environmental and public health organisations are saying the opposite: science is showing that risk assessments and safety studies – notably for pesticides and GMOs – should be strengthened also in Europe.12

Yet whilst demanding more 'sound science', at the same time industry conceals the data produced by its research. Industry is demanding strong rules for confidentiality of business information within TTIP13, and fighting transparency initiatives wherever they pop up. For instance, a chorus of biotech, pesticide and even food lobbies have made their opposition loud and clear to an EFSA initiative to facilitate public access to data from safety studies done by the industry,14 a long standing demand from civil society and scientists alike.

Box 1: Food safety agencies independent? |

| One thing industry strongly advocates is an intense cooperation and communication between the respective food safety agencies, the European Food Safety Agency (EFSA) and the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA). This would lead to a convergence in regulation and assessment of substances in food.15 But both agencies are not only heavily relying on industry studies while assessing the food safety of products, both are strongly associated with conflicts of interest with industry. An analysis of the EFSA panels has shown that almost 60% of the experts have ties with the industry itself.16 The very risk assessment guidelines for GMOs were to an important extent influenced by the former GMO panel chair who had ties to the International Life Sciences Institute (ILSI), a biotech lobby group with offices in Washington and Brussels.17 And if EFSA is bad then the US counterpart of EFSA, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) is even worse, whose staff is often going through the revolving doors, notably with Monsanto.18 Therefore, having these two agencies playing a key role in regulatory cooperation between the EU and the US, will not make us have less to worry about. |

Mutual recognition – trade-speak for lowering standards

Mutual recognition between the two trading blocs of a given set of (safety) standards is a trade facilitation tool. With mutual recognition, a US product (that meets the US standards) would automatically be allowed into the EU (even if it does not meet EU standards), and vice versa. In the words of the food industry, mutual recognition means that each government has "full sovereignty" over its own regulations for domestically produced products, but a "limited ability to project those policies onto its trade partners or to determine the characteristics of products consumed domestically”.19 European Trade Commissioner De Gucht also advocates for the mutual recognition of EU and US regulations across a broad range of sectors: "This is the most efficient way to connect our two systems to allow our businesses to operate more effectively across the Atlantic."20

Mutual recognition means easier market access for exporters. But it can be a very damaging approach from an environmental and public health perspective. As consumer group the Transatlantic Consumer Dialogue (TACD) says: “Mutual recognition of standards is not an acceptable approach since it will require at least one of the parties to accept food that is not up to the requirements for domestic products."21 TACD and other NGOs have identified many areas where the mutual recognition of different protection levels would create serious problems, for example for animal welfare rules, food labelling, and hygiene- and safety-standards in the food and agriculture sector, including those rules relating to GMOs and pesticides. And while mutual recognition can be bad for consumers, it can also be a threat to farmers' and food producers' livelihoods as it leads to unfair competition. This is likely to lead to internal pressure for lowering standards in the EU. (See box 2).

| Box 2: The message to farmers: you've got to adapt |

| How would mutual recognition lead to unfair competition? If for instance the amount of pesticide residues allowed in a product is higher in the US than in the EU, with mutual recognition US farmers would still be able to export that product to the EU even though it would not meet EU standards (that European producers would still have to meet obviously). Similarly, the European food industry lobby is demanding mutual recognition for food additives that are forbidden in the US but not in the EU.22 The European meat sector for example is one that could be strongly impacted by TTIP, in particular through mutual recognition of standards. In the EU this is already a highly polluting and cruel industry, but the way things are done in the US is even worse. US livestock factory farms for instance use large amounts of hormones, and more antibiotics that are causing the public health threat of resistant super-bacteria.23 Olga Kikou of Compassion in World Farming says: "There is no or very little animal welfare legislation in the US, which means that when those animal products enter the EU market, they will jeopardise our standards here as well as future legislation, which will then lead to further intensification of animal farming in the EU.”24 The farming lobby COPA-COGECA, while seeming to be very supportive of the TTIP negotiations, is in fact very worried about the different levels of standards: "European citizens expect farmers to implement increasingly expensive and higher production standards while imported products do not have to meet the same requirements. This inconsistency needs to be resolved".25 The dairy sector is under similar pressure. Sieta van Keimpema, Vice Chair of the European Milk Board, a European umbrella organisation representing dairy farmers is very concerned about TTIP: “We will sink to the lowest standards or we will have an enormous distortion of competition. Milk producers in the region with the higher standards and the higher cost will eventually lose this race to the bottom.”26 But Eucolait, the lobby group of international dairy traders, welcomes the attack on European standards: a number of “sanitary and technical barriers to trade need to be addressed.... Ideally, the TTIP would result in a mutual recognition of the two food safety systems as equivalent or comparable.”27 The European Commission’s attitude appears in line with this, apparently little concerned about farmers' livelihoods in Europe. When confronted with concerns from European producers at the Forum for the Future of Agriculture in Brussels (a Syngenta lobby event) in April 2014, the chief of Cabinet of European Trade Commissioner De Gucht, Marc Vanheukelen, said, "[T]rade is about trying to exploit each others' comparative advantages. We have high costs for labour and energy in Europe. The point is to stay competitive. This is the nature of the opening of markets. You've got to adapt." Then came a question from the chair: “There are gains and pains?” And Vanheukelen responded: “Absolutely. Gains from trade come from efficiency gains, competitive pressure, economies of scale, more investment. This is how each trade deal generates growth.” “The pains” he refers to mean many European producers will no longer be able to compete. The pressure to lower standards in Europe to 'resolve the inconsistencies' will be strong, and far more likely to succeed than the other solution: raising standards in the US. Moreover, De Gucht may therefore not be lying technically, when he claims that standards are not going to be lowered in Europe. EU rules may not initially be changed. But taking into account the above, it is hard to see how this will not eventually lead to a race to the bottom: harmonised, lower standards. |

Next step: harmonisation

For the industry, mutual recognition is only the first step. After US standards on pesticides, for example, are accepted by the EU for products that it imports, the next step for the industry is to get those standards in the EU down to the same lower level. For instance, the pesticide lobby document by Croplife and ECPA demands "significant harmonisation" between the US and EU rules for establishing limits for how much of a pesticide can remain in food and feed products.

At the Forum for the Future of Agriculture, the annual Syngenta lobby event (the company is a member of both ECPA and Croplife), Syngenta's Chief Operating Officer John Atkin said: "How do you make sure that what you grow in one place, you can export to another? It's really challenging. Mutual recognition would be a start, but common shared [product] reviews and common standards would be the end point."28 And, indeed in the last TTIP negotiation round in the US in March 2014, the US Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) suggested that “it might be possible to… converge or harmonise” these accepted pesticide residue levels for certain crops.29 This, and doing "joint reviews", could be activities "that would make TTIP meaningful for this important sector", according to the EPA.

To the question of whether he was at all concerned that ongoing talks might lead to a reduction of European food safety standards, Atkin juggled a hot potato by replying: “[TTIP] can only be a good thing, if this comes to pass. How can it be that very developed regions of the world, with the best scientists, have a different view on what constitutes food safety? The tests that we all have to do are not aligned. As a consumer, please, I want high standards, but please let's have them harmonised.”30Harmonisation ties in neatly with the next – and biggest – step: regulatory cooperation.

Locking in the future: regulatory cooperation

TTIP, as we have seen, will pose a clear and present danger of lowering existing EU (and US) food and agriculture standards. But the agreement could also considerably increase corporate influence over the political decisions that will shape the agriculture of the future, closing the door on the possibility of moving the EU and the US towards very different food policies. Under TTIP’s chapter on 'regulatory cooperation', any future measure that could lead us towards a more sustainable food system, could be deemed 'barriers to trade' and thus refused before it sees the light of day.

Big business groups like BusinessEurope and the US Chamber of Commerce have been pushing for this corporate lobby dream scenario before the EU-US trade negotiations even began. What they want from regulatory cooperation is to essentially co-write legislation and to establish a permanent EU-US dialogue to work towards harmonising standards – long after TTIP has been signed.31

Despite earlier reservations, the Commission seems to now go along with this corporate dream. Leaked EU proposals from December 2013 outline a new system of regulatory cooperation between the EU and the US, that will enable decisions to be made without any public oversight or engagement. Business will be involved from the beginning of the process, well before any public and democratic debate takes place, and will have excellent opportunities to ditch important initiatives to improve food standards or protect consumers.

Lobbyists would get an unprecedented opportunity to intervene and block new policy areas. For instance, an 'early warning' system for “any regulatory and legislative initiatives with potential trade impact as of the planning stage” would be implemented; “cost-benefit” and “trade impact” analyses for proposed new regulatory or legislative initiatives would be required; and there would be surveillance of new regulations initiated by lower level authorities such as European governments or American states. An "oversight body” would be created, mostly referred to as an EU-US “Regulatory Council”, which would “consider new priorities for regulatory cooperation – also in response to proposals from stakeholders”.32 (For more details on the Commission’s regulatory cooperation agenda and how it mirrors corporate lobby proposals, see CEO’s report 'Regulation: None of our business?' from December 2013.33)

This is a clear reflection of the business demands such as those from ECPA and Croplife, involving industry at the earliest stages of any new regulatory initiative: "This will... ensure minimum unfair competitive impact before regulation is proposed and implemented.” Or, as the FoodDrinkEurope/COPA-COGECA document states, the ultimate goal is that “no new regulatory barriers are introduced.” One thing industry strongly advocates in this context is an intense cooperation and communication between the respective food safety agencies, the European Food Safety Agency (EFSA) and the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA). This would lead to a convergence in regulation and assessment of substances in food.34 But both agencies are not only heavily relying on industry studies while assessing food safety of products, both are strongly associated with conflicts of interest with industry (see box 1).

ECPA and Croplife explicitly add that a system of regulatory cooperation would prevent "bad decisions", avoiding them having to take governments to court later. This clearly hints at the situation of their member corporations, biotech and pesticide giants Syngenta and Bayer, who are taking the European Commission to court over its partial ban on three insecticides from the neonicotinoid family, because of their deadly impact on bees.

If TTIP is to include an Investor to State Dispute Settlement mechanism (ISDS), corporations will have an even stronger tool to sue either of the two blocs, or individual EU member states, including for measures taken at a lower governmental level. Even if progressive forces were to seize more power in the EU and/or in the US, pushing for higher safety levels or the ban of certain substances, the industry will fight back in private international investor-state tribunals. Since Syngenta for instance is based in Switzerland, but is also registered in the EU and US, could it not sue both of them? When this question was posed at a Brussels conference to Syngenta Chief John Atkin he replied, laughing: "Yes! All of the above. We are a good example of a global company."

The idea of industry and the Commission behind regulatory cooperation is to make TTIP a 'living agreement', with ongoing negotiations, therefore not confined to what they can agree on in the short term. Even if the final TTIP text does not include explicit concessions on food or environmental standards, regulatory cooperation would pave the way for these concessions in the future. This makes it one of the most dangerous part of TTIP, which will lock in future policy making in many different areas.

| Box 3: Implementation phase as a loophole |

| Several organisations have warned that increased alignment of EU and US policies can also happen in a more invisible fashion, in their implementation phase. For instance, EU officials have said that the EU's GMO laws are 'non negotiable'. But consumer group TACD points out that in the case of GMOs, the EU could end up adjusting the implementation rules, away from parliamentary and public scrutiny, rather than the laws themselves. This could include the redefining of thresholds for contamination with GMOs unauthorised in the EU (and therefore illegal) in food or seed,35 or lowering safety checks for GMOs.These are technical aspects that can be changed by the Commission without actually changing the EU GMO laws.36 |

TTIP at work

There are clear, concrete examples that show how TTIP is already at work, lowering standards in the EU. A case in point is the recent decision by the Commission to lift the EU ban on meat treated with lactic acid, a demand from the US. The European Parliament was put under great pressure by DG Trade to let this pass – for the sake of TTIP.37

But another, much bigger initiative is currently under industry attack: EU efforts to deal with endocrine disrupting chemicals (EDCs). This is the number one item on the list of the united pesticide lobby (ECPA and Croplife) of regulatory initiatives that they hope can be killed through TTIP. Endocrine disrupting chemicals are widespread in our food and environment, and interfere with our hormonal systems. More than 870 potential EDCs have been identified so far, including widely used products such as the herbicide glyphosate (Roundup), bisphenol-A, a major ingredient in many plastics. Both the EU’s 2009 pesticide regulation and the European chemicals package (REACH) demand that the EU take action on these chemicals.

The transatlantic pesticide lobby has started scaremongering about economic losses if the EU were to take action on endocrine disruptors. Croplife America’s lobbyist Doug Nelson says: “The proposed policies for endocrine disruptors... could block more than $4 billion, or 40 percent, of US agricultural exports to the EU in addition to exports of crop protection active ingredients, and imperil TTIP.”38 Also, despite a wealth of scientific evidence that point at the dangers of endocrine disruptors, they kept creating doubt by stressing the need for 'sound science'.

DG Environment was in the lead, and in early 2012 published a report by renowned experts in the field, urging that action should be taken. The first important step would be to decide on scientific criteria to define endocrine disruptors. A draft list was published in February 2013. But the process got derailed by other actors within the Commission, following strong industry lobbying. First, DG SANCO interfered by announcing that it had tasked EFSA with forming a scientific opinion on endocrine disruptors, effectively creating a parallel process. Then – in June 2013 – Commission Secretary-General Catherine Day ordered an impact assessment. A group of MEPs closely following the issue, wrote in a letter to the former President of the European Commission Barroso: "This decision is surprising, as one would expect scientific criteria to be based on objective scientific studies and not on an impact assessment, which is rather a tool to inform political decisions."39

So much for 'sound science'! One of the MEPs signing the letter, Green member Michele Rivasi, indeed suspects that the Commission is stalling the process, "in order to buy time until the EU-US trade deal would be signed.”40 This is obviously the industry's hope as well. 41

This is just one example that illustrates how an industry friendly TTIP regime can jeopardise future improvements in environmental and food safety regulations. To take action against these chemicals is a commitment the EU has already made, but which is now being heavily attacked by transnational corporations, using TTIP as a demolition hammer.

Warned is forearmed

The reassurances from EU and US negotiators that “food standards will not be lowered” cannot be trusted. The public needs to know that because of TTIP, imports may be allowed that do not meet local standards. Farmers should be aware that they will suffer more and unfair competition. We can also expect that standards will be lowered, or may be undermined during the implementation phase. Regulatory convergence will fundamentally change the way politics is done in the future, with industry sitting right at the table if they get their way.

When all these elements are taken together, TTIP reveals itself as the ultimate tool of EU and US agribusiness to counter any 'inconvenient' food-related standard. Anyone engaged in creating or arguing for a food and farming system that produces healthy food and is ecologically sustainable and socially just should roll up their sleeves to stop TTIP.

- 1. See for instance the warnings of:

Transatlantic Consumers Dialogue, 16 September 2013,

http://test.tacd.org/wp-content/uploads/2013/09/TACD-FOOD-34-13-The-Approach-to-Food-and-Nutrition-Related-Issues-in-the-TTIP.pdf

Grain, 10 December 2013, http://www.grain.org/article/entries/4846-food-safety-in-the-eu-us-trade-agreement-going-outside-the-box

FoEE and IATP, October 2013, http://www.foeeurope.org/sites/default/files/publications/foee_iatp_factsheet_ttip_food_oct13.pdf

ClientEarth and CIEL, 10 March 2014, http://www.ciel.org/Chem/TTIP_10Mar2014.html

IATP, May 2014, http://www.iatp.org/documents/10-reasons-ttip-is-bad-for-good-food-and-farming - 2. Press statement by EU Trade Commissioner Karel de Gucht, 18 February 2014, http://europa.eu/rapid/press-release_STATEMENT-14-12_en.htm

- 3. http://www.reuters.com/article/2014/03/26/us-usa-eu-summit-trade-idUSBRE...

- 4. Inside U.S. Trade, June 19, 2014, Vilsack Pokes At Major EU TTIP Red Lines On GMOs, Hormone Beef

- 5. http://corporateeurope.org/international-trade/2014/07/who-lobbies-most-...

- 6. http://corporateeurope.org/sites/default/files/email-to-ecpa.pdf

- 7. http://ec.europa.eu/enterprise/policies/international/cooperating-govern...

- 8. These two documents are frequently referred to in this article.

- FoodDrinkEurope/COPA-COGECA position, 23 January 2014, www.copa-cogeca.be/Download.ashx?ID=1130938

- Croplife America/European Crop Protection Association, 7 March 2014, http://corporateeurope.org/sites/default/files/attachments/ecpa-cla_ttip_position_-_paper_10-03-14.pdf - 9. Colin Macilwain in Nature, April 2014, http://www.nature.com/news/beware-of-backroom-deals-in-the-name-of-science-1.15046?WT.ec_id=NATURE-20140417#auth-1

- 10. Croplife America and European Crop Protection Association (ECPA), Proposal on EU-US Regulatory Cooperation, March 7 2014. http://corporateeurope.org/sites/default/files/attachments/ecpa-cla_ttip_position_-_paper_10-03-14.pdf

- 11. European Commission, TTIP Report of the fourth negotiation round, 21 March 2014. On file with CEO.

- 12. Some examples: there is intense debate around the fact that our risk assessment laws do not demand chronic feeding studies (only, and not always, standard 90 days studies), allow for studies to be carried out by the corporation itself (not by an independent lab), and fail to take into account the so-called 'cocktail effect' (the effect of being exposed to a mixture of many chemicals at the same time).

- 13. Croplife America and European Crop Protection Association (ECPA), March 7 2014. See footnote 8.

- 14. EFSA press release, 14 January 2013, http://www.efsa.europa.eu/en/press/news/130114.htm

- 15. http://corporateeurope.org/sites/default/files/attachments/ecpa-cla_ttip_position_-_paper_10-03-14.pdf

- 16. Corporate Europe Observatory report 'Unhappy Meal', October 2013. http://corporateeurope.org/efsa/2013/10/unhappy-meal-european-food-safety-authoritys-independence-problem

- 17. See for instance CEO and Earth Open Source's report 'Conflicts on the Menu', February 2012, http://corporateeurope.org/efsa/2012/02/conflicts-menu

- 18. http://grist.org/article/2009-07-08-monsanto-fda-taylor/

- 19. FoodDrinkEurope/COPA-COGECA, January 2014. See footnote 8.

- 20. http://europa.eu/rapid/press-release_MEMO-13-835_en.htm

- 21. http://www.consumersinternational.org/media/1402104/tacd-food-resolution-on-the-approach-to-food-and-nutrition-related-issues-in-the-ttip.pdf

- 22. FoodDrinkEurope/COPA-COGECA, January 2014; an example is the often questioned colourant E150a ('caramel'). See footnote 8.

- 23. Allen Hershkowitz of the US Natural Resources Defence Council, speaking at the Syngenta Forum for the Future of Agriculture, 1 April 2014, Brussels.

- 24. Personal communication, Olga Kikou, 25 April 2014.

- 25. FoodDrinkEurope/COPA-COGECA, January 2014. See footnote 8.

- 26. Personal communication, Sieta van Keimpema, 22 April 2014.

- 27. Eucolait website, Eucolait position on the TTIP, 11 September 2013. http://www.eucolait.be/positions-a-letters/trade/14548-eucolait-position-on-the-ttip-/download

- 28. Forum for the Future of Agriculture, 1 April 2014, Brussels. http://www.forumforagriculture.com/ffa-tv.html

- 29. European Commission, TTIP Report of the fifth negotiation round, 3 June 2014. On file with CEO.

- 30. http://www.vieuws.eu/food-agriculture/ttip-syngenta-chief-calls-for-harmonized-safety-standards/

- 31. http://corporateeurope.org/sites/default/files/businesseurope-uschamber-paper.pdf

- 32. http://corporateeurope.org/sites/default/files/ttip-regulatory-coherence-2-12-2013.pdf; http://europa.eu/rapid/press-release_SPEECH-13-801_en.htm

- 33. http://corporateeurope.org/trade/2013/12/regulation-none-our-business

- 34. http://corporateeurope.org/sites/default/files/attachments/ecpa-cla_ttip_position_-_paper_10-03-14.pdf

- 35. It should be noted that in the past, rules were already adapted to allow contamination with illegal GMOs in animal feed. Both the food (FoodDrinkEurope), animal feed (FEFAC), and the seeds industry (ESA, EuropaBio) have been lobbying for years to get rid of the EU's zero-tolerance policy for contamination with illegal, non authorised GMOs of human food, animal feed and seeds. Animal feed is the first case where a threshold for tolerated presence of illegal GMOs was set, presented as responsible because these GMOs are 'recognised as safe' by the exporter, the US. Food and seeds are next on industry's list, and TTIP could accelerate the break down of the zero-tolerance policy in these areas.

- 36. Transatlantic Trade and Investment Partnership - Questions and Answers. BEUC, FOEE, EPHA, TACD. http://www.beuc.eu/publications/x2013_093_qa-transatlantic_trade_and_investment_partnership.pdf

- 37. See statements by MEP Roth-Berendt in ARD program 'Monitor', January 30 2014, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ljneHxc1rgc#t=149

- 38. http://www.ecpa.eu/news-item/regulatory-affairs/03-14-2014/1312/crop-protection-industry-urges-stronger-regulatory-fram

- 39. http://www.michele-rivasi.eu/au-parlement/lettre-au-president-de-la-comm...

- 40. http://www.michele-rivasi.eu/medias/perturbateurs-endocriniens-et-traite...

- 41. Even if action were taken on EDCs, the pesticide lobby groups Croplife and ECPA stress that, "there are still opportunities for regulatory convergence in the data requirements and the scientific assessment and risk assessment procedures”. Here we see again how the implementation phase can provide a loophole that would allow negotiators to say that 'standards are now lowered'. While in reality, technical aspects of the risk assessments for can be changed, without the law itself being touched.

Comments

You have nailed it! " Anyone engaged in creating or arguing for a food and farming system that produces healthy food and is ecologically sustainable and socially just should roll up their sleeves to stop TTIP. "

TTIP projects itself as the organization who is working in the interested of farmers and making sure that governments don't lower food safety standards which is far far away from truth.

Your views are well-defined and you have clearly spoken the truth about the multi-national companies that are growing their pockets at the expense of others. Need your organization to help the poor farmers, so that we don't end up in a famine situation.