A bird’s eye view on 15 years CEO

CEO chronology 1997-2012

CEO took its first steps in May 1997, when the report “Europe, Inc. – Dangerous Liaisons between EU Institutions and Industry” was published. The report was launched to a wider audience at the Summit From Below, a pan-European conference parallel to the EU summit in Amsterdam. The report was the first comprehensive overview of the influence exerted by the European Roundtable of Industrialists and other corporate lobby groups over key EU policies and the process of European unification. What started out as an ad-hoc research project soon became a concerted effort to throw light on corporate efforts to influence decision-making. In September 1997, the first issue of the Corporate Europe Observer newsletter was published, circulated by email to activists, academics and other interested individuals. CEO continued publishing the quarterly Corporate Europe Observer until 2002.

In 1998 CEO played a key role in the broad opposition that led to the termination of the OECD negotiations on the Multilateral Agreement on Investment (MAI). Drafted in the heydays of neoliberalism in Europe and with heavy input from corporate lobby groups such as the International Chamber of Commerce, the OECD negotiators wanted the MAI to become a global treaty outlawing all obstacles to cross-border investment flows. CEO became a central actor in the international coalition of activists and campaigners that sounded the alert about the disastrous impacts such radical deregulation would have for the environment and development. CEO research, based on internal EU documents accessed via freedom-of-information requests, showed the European Commission acting as a staunch defender of the most neoliberal version of the MAI. Rapidly growing grassroots opposition against the MAI caused governments to introduce a break in the negotiations. By October 1998 the MAI talks collapsed altogether.

During 1999 – the year of ‘the Battle of Seattle’ – CEO published a series of reports exposing the corporate influence on the EU’s campaign for a WTO investment agreement (based on the MAI), a part of a broader proposal for launching a so-called Millennium Round of new WTO liberalisation talks. In these years, CEO research uncovered a range of examples of how the EU’s agenda for new global trade negotiations was deeply biased towards promoting corporate interests. An example was the services liberalisation talks (GATS), where the European Commission even co-founded a new corporate lobby group to secure optimal input from and cooperation with large corporations: the European Services Forum.

In Spring 1999 CEO opened its first office in Paulus Potterstraat 20 in Amsterdam’s museum quarter, on the top floor of the building mainly used by the Transnational Institute (TNI)

In early 2000, Pluto Press published our book “Europe, Inc. – Regional and Global Restructuring and the Rise of Corporate Power”. Like our 1997 report, this 256-page book raised the alert to the threats arising from excessive corporate political power, but covered a far wider range of issues, based on interviews with a number of lobbyists. Translated editions of the book appeared in French, Danish, Slovak, German, Finnish, Spanish and other languages. In October 2000, on the eve of the UN’s climate summit (COP-6) and the parallel Climate Justice Summit in The Hague, CEO published the “Greenhouse Market Mania” report, documenting attempts by corporate lobby groups to prevent genuine progress in UN climate talks and the emergence of pseudo-solutions such as carbon emissions trading.

An important focus in CEO’s research and campaigning at this time was the TransAtlantic Business Dialogue (TABD), a body of US and EU-based corporations. The European Commission and the US government had awarded the TABD the task of identifying obstacles to trans-Atlantic trade and investment, obstacles which they in turn would act to remove. Predictably, the corporations defined ‘obstacles’ broadly and used the TABD as a tool for watering down or halting new environment or consumer protection measures. The TABD was increasingly seen as a symbol of a flawed and undemocratic model of globalisation, in which corporate executives were granted inappropriate political powers. The annual TABD summits became the target of non-violent protest demonstrations for several years in a row, for instance in November 2001 in Stockholm where CEO co-hosted a well-attended counter-summit.

Earlier in the autumn of 2001, the Financial Times had included CEO in its list of the 25 most important organisations in the “anti-globalisation movement”, a recognition we welcomed although “anti-globalisation” was a poor description of the global movement opposing neoliberal globalisation policies that were leaving economies and societies at the mercy of large corporations and financial markets.

In the run-up to the UN’s Rio+10 summit on sustainable development in Johannesburg in the summer of 2002, CEO published a series of in depth articles exposing the ambitious corporate greenwash and lobbying campaign for ‘voluntary action’ and against binding rules to enforce responsible conduct of transnational corporations. As part of the Alliance for a Corporate-Free UN, CEO campaigned against the abuse of the UN’s Global Compact for greenwash purposes and the increasing cooption of the UN agencies via partnerships with big business.

In June 2002 CEO won its first complaint to the European Ombudsman, when the then Ombudsman Jacob Söderman condemned the European Commission’s secrecy over its involvement in the TransAtlantic Business Dialogue (TABD). The Commission had refused access to information arguing that its involvement in the TABD events were ‘negotiations’ and therefore fell outside the scope of transparency rules. The Ombudsman disagreed with this secrecy and found the Commission guilty of maladministration.

In 2003 CEO started a several year effort to expose the EU’s use of trade talks and aid policy to impose water privatisation in developing countries. We took the first steps in developing a strong international network to promote alternatives to privatisation on the fringes of the World Water Forum in Kyoto, Japan. We exposed the European Commission’s close cooperation with private water corporations in drawing up its demands for the WTO’s services sector negotiations (GATS). In the run-up to the WTO summit in Cancun in autumn 2003, we exposed the EU’s aggressive agenda promoting the interests of EU-based corporations, including its record of arm-twisting and bullying of developing country negotiators.

In 2004, CEO launched several new initiatives to put corporate lobbying in Brussels in the spotlight. We started offering guided tours of Brussels’ EU quarter, in which interested citizens were introduced to the buildings from where companies, lobby groups and think tanks were based. Later in the year we published the “Lobby Planet Guide to Brussels”, a tongue-in-cheek guidebook with maps, photos and routes (later also published in French, Dutch and German).

In 2004, CEO launched several new initiatives to put corporate lobbying in Brussels in the spotlight. We started offering guided tours of Brussels’ EU quarter, in which interested citizens were introduced to the buildings from where companies, lobby groups and think tanks were based. Later in the year we published the “Lobby Planet Guide to Brussels”, a tongue-in-cheek guidebook with maps, photos and routes (later also published in French, Dutch and German).

In the autumn of 2004, a new Commission team took office, led by Jose Manuel Barroso. Together with over 70 other non-governmental organisations, CEO wrote to Barroso and other new Commissioners urging them to “act to curb excessive corporate lobbying power”. The letter expressed concern about the “powerful and increasingly undemocratic role [of industry lobbyists] in the EU political process” and concluded that “as a first step in addressing these problems, Europe needs far stricter ethics and transparency requirements”.

The Commission’s first response was to dismiss our concerns, but in early 2005 we received a surprise invitation from Siim Kallas, the new Commissioner for administration. At this meeting Kallas, newly arrived in Brussels from Estonia, told us that he also thought there was a lack of transparency around lobbying in Brussels and that he was going to launch an initiative to change this. Some weeks later Kallas presented the European Transparency Initiative, which included a proposal for creating an EU lobby transparency register. Kallas’ statements about lobbyists having to register and disclose who they lobby for and with which budgets caused an angry uproar inside the Brussels bubble. It was in the context of a growing backlash against Kallas’ initiative that CEO, together with numerous civil society allies, in the summer of 2005 launched the Alliance for Lobby Transparency and Ethics Regulation in the EU (ALTER-EU). Over 160 civil society groups supported ALTER-EU’s call for “Ending corporate privileges and secrecy around lobbying in the European Union” and the coalition became a strong, high-profile voice insisting on the need for a mandatory, high-quality lobby register and for other measures to roll back corporate influence in decision making.

We published in depth reports exposing how deceptive lobby campaigns by the chemical, the bromine and the F-gas industries seriously weakened EU environmental regulation of chemicals.

Later in 2005, CEO co-organised the first Worst EU Lobbying Award, jointly with LobbyControl, Spinwatch and Friends of the Earth Europe. The ‘Campaign for Creativity’ won the award for its deceptive ‘grassroots’ lobby campaign for software patents which had in fact been run by a public affairs consultancy, Campbell Gentry in London, with undisclosed financial support from Microsoft and other software multinationals.

Between 2005 and 2010, we organised five Worst EU Lobbying Awards, with winners including Exxon Mobil, Goldman Sachs, the German Atomic Forum as well as Porsche, Daimler and BMW.

Also in 2005, we jointly published a book on Reclaiming Public Water with the Transnational Institute, presenting real-world examples of successful public water management as alternatives to privatisation. The book was later translated into 15 languages and gave birth to a global network with the same name.

2006 saw a further breakthrough in the debate about EU lobbying, as a result of very intensive campaigning and awareness-raising by CEO and our ALTER-EU allies. The debate shifted from whether there was a need to regulate lobbying to the question of how to achieve effective transparency. In addition to campaigning with ALTER-EU for mandatory lobby transparency, CEO also contributed to the debate by exposing climate sceptic think tanks funded by the oil industry, the lobbying by the nuclear industry and scandals such as industry using cross-party groups of MEPs as vehicles for lobbying.

2007, CEO’s tenth anniversary year, started with a bang as our pressure resulted in energy industry lobbyist Ralph Linkohr being fired from his position as Special Adviser to then Energy Commissioner Andris Piebalgs. Linkohr ran a consultancy that was lobbying for large energy companies and advertised his Special Adviser’s status on his consultancy’s website. The Commission followed up by releasing, for the first time ever, a full list of the 55 Special Advisers working for EU Commissioners. In the months after, conflicts of interests rules for Special Advisers were introduced, but the rules soon proved too weak to prevent big business lobby veteran Etienne Davignon from acting as a Special Adviser on development in Africa.

In August, CEO won an important victory when the European Ombudsman condemned the European Commission and its Directorate-General Trade – led by Peter Mandelson – for its habit of blanking out the names of industry lobbyists in correspondence, minutes of meetings and other documents released under EU transparency rules.

The winner of the Worst EU Lobbying Award in December 2007 was a coalition of lobby groups which had used misleading information and greenwash to influence EU decisions to increase the use of agrofuels in transport. CEO was one of the first groups to sound the alarm about the dangers of promoting the use of agrofuels produced in the South including the grave impacts on the environment and local communities. We helped bring together a North-South alliance of organisations and movements to fight the proposed EU agrofuel target. CEO also exposed the role of industry-controlled advisory groups including Biofrac and EBFTP which played a strong role in shaping the allocation of EU research funding and other promotion of agrofuels.

In spring 2008, CEO and ALTER-EU won an important breakthrough when the European Parliament voted for a mandatory lobby transparency register with reliable financial information. Disappointingly, the lobby transparency register launched by the European Commission in June, was voluntary and the rules on financial reporting were full of loopholes. Still it was a step in the right direction to have, for the first time ever, an EU lobby register, with lobbies expected to disclose who they were lobbying for and with what budgets.

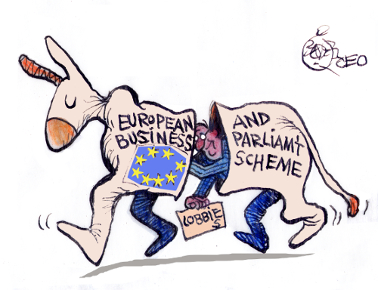

At the end of 2008, the European Business and Parliament Scheme (EBPS) – an umbrella group which brings together representatives from 28 multinational companies and MEPs – was forced to move out of the European Parliament. This decision followed pressure from CEO and others about the EBPS’s use of rent-free offices inside the Parliament to help its corporate members influence EU decision-making.

At the end of 2008, the European Business and Parliament Scheme (EBPS) – an umbrella group which brings together representatives from 28 multinational companies and MEPs – was forced to move out of the European Parliament. This decision followed pressure from CEO and others about the EBPS’s use of rent-free offices inside the Parliament to help its corporate members influence EU decision-making.

Together with our allies in the Seattle-to-Brussels network, we campaigned against the EU’s new Global Europe strategy for international trade negotiations. The Global Europe strategy had been virtually co-drafted by the lobby group BusinessEurope and revealed a further extension of the flawed approach of promoting the interests of large corporations, often at the expense of the poorest and the environment.

In the run-up to and during the UN climate summit in Poznan, we exposed the negative influence of industry lobbying on the EU’s position and on the negotiations in general.

In early 2009, CEO moved its office from Amsterdam into the newly opened Mundo-B building in Brussels. With the crucial climate summit in Copenhagen approaching, we co-organised the Climate Greenwash Awards, won by energy giant Vattenfall. And during the Copenhagen summit itself we presented the Angry Mermaid Award for corporate lobbying against action on climate change. On the basis of online votes cast by 10,000 people, Monsanto won for its aggressive marketing of genetically modified (GM) crops as a ‘solution’ to climate change.

In early 2009, CEO moved its office from Amsterdam into the newly opened Mundo-B building in Brussels. With the crucial climate summit in Copenhagen approaching, we co-organised the Climate Greenwash Awards, won by energy giant Vattenfall. And during the Copenhagen summit itself we presented the Angry Mermaid Award for corporate lobbying against action on climate change. On the basis of online votes cast by 10,000 people, Monsanto won for its aggressive marketing of genetically modified (GM) crops as a ‘solution’ to climate change.

Also in 2009 ALTER-EU published a major report documenting how the European Commission’s numerous advisory groups on financial regulation were dominated by banking industry lobbyists. Against the background of the financial crisis, the capture of the EU’s decision-making was a major scandal that over the next months was covered in media across Europe. CEO published extensively on financial lobbying, exposing the secrecy around big banks lobbying in Brussels and the deceptive lobbying by the hedge funds and venture capital industry.

We had a major success in our work on promoting alternatives to water privatisation when the European Commission recognised the potential of public-public partnerships (PuPs – not-for-profit cooperation between public utilities) in improving access to water for the poorest. As a result a separate budget for PuPs was included, for the first time ever, in the new round of EU development aid for water projects in Africa.

Soon after the new Commission team (Barroso-2) had taken office in early 2010, the first revolving door scandals emerged as ex-Commissioners took jobs in large companies, likely to involve lobbying or other conflicts of interest. CEO, together with ALTER-EU allies, monitored and exposed the industry jobs of ex-Commissioners like McCreevy, Verheugen and Ferrero-Waldner. Our demands for far stricter rules were widely supported, as became clear when an Avaaz petition was signed by over 50,000 people. The European Parliament blocked the approval of parts of the Commission’s budget to force a change of rules, including a cooling-off period of several years for lobby jobs. The new rules eventually introduced by the Commission only went half-way to what was needed to effectively prevent revolving door scandals. The Commission’s weak rules around conflicts of interest was also one of many issues highlighted in the book “Bursting the Brussels Bubble”, published by the ALTER-EU coalition. The book outlines ten key transparency and ethics reforms to curb undue lobbying influence.

Among the many reports we have published exposing lobbying scandals it is worth highlighting our June 2010 report on the massive industry lobby campaign to determine the outcomes of the EU’s food labeling system. This often very aggressive lobby campaign has according to industry estimates amounted up to 1 billion Euro, including for the development of the less transparent food labelling system eventually endorsed by MEPs. Together with the European Beekeeping Coordination, CEO exposed the fact that the EU allows industry ‘experts’ to be directly involved in assessing the impact of pesticides on bees, a scandalous situation considering that pesticides are a likely cause of bee starvation.

“Trade Invaders”, our in depth report on the industry capture of the trade negotiations between the EU and India, was widely covered by media in Europe and India. It later formed the basis of the court case we have launched against the European Commission because of the privileged access to information it grants industry lobby groups.

In 2011, there were several significant breakthroughs in the debate about conflicts of interest at the EU institutions. CEO published a series of reports exposing problems at the EU’s food safety agency EFSA, where numerous members of powerful panels have close links to food industry lobbies. The pressure on EFSA to take steps to avoid undue influence grew throughout the year and led to new rules on conflicts of interest that might signal the beginnings of a new and stricter approach. A new coalition of environment and public health groups has been formed to demand a radical change in the way food safety is assessed.

In 2011, there were several significant breakthroughs in the debate about conflicts of interest at the EU institutions. CEO published a series of reports exposing problems at the EU’s food safety agency EFSA, where numerous members of powerful panels have close links to food industry lobbies. The pressure on EFSA to take steps to avoid undue influence grew throughout the year and led to new rules on conflicts of interest that might signal the beginnings of a new and stricter approach. A new coalition of environment and public health groups has been formed to demand a radical change in the way food safety is assessed.

CEO also, jointly with other groups, filed a court case against the European Commission for the obscure and secretive manner in which it approves voluntary schemes to certify agrofuels for the EU market. One of these is the Round Table on Responsible Soy, a greenwash scheme that promotes genetically modified soy as ‘responsible’.

Together with allies in ALTER-EU, we successfully advocated stricter conflicts of interest rules for MEPs. In the wake of the cash-for-amendments scandal in spring 2011, the Parliament developed a new Code of Conduct. The Ombudsman ruled in our favour in a complaint about Pat Cox, a lobbyist for Microsoft and Pfizer, acting as a Special Adviser to the Commissioner for Consumer Protection. In the autumn, the European Parliament decided to freeze parts of the European Commission’s budget until the Commission introduced new rules to prevent industry capture of its expert groups. With ALTER-EU we launched a new campaign focusing on Commission officials going through the revolving door into industry lobby jobs.

Together with CarbonTradeWatch, we published a series of reports on industry lobbying undermining EU climate policies, with lobbying influence contributing to the failure of the EU’s emissions trading system.

Our new edition of the LobbyPlanet guidebook attracted widespread coverage in German media. We published several in depth reports raising the alarm over the EU’s new ‘economic governance’ package and other aspects of the EU's neoliberal response to the deepening crisis. These policies, which mirror demands from big business lobby groups, impose austerity as the only option and drastically expand the European Commission's powers to intervene in national budgets and other policies.

These issues are the focus of our 15-years anniversary conference, May 5-6 2012 in Brussels (“EU in Crisis: analysis, resistance and alternatives”. For more about our activities and achievements in 2012, visit our website.