Stopping the next 'cash for access' lobby scandal

The 'cash for access' scandal in the UK has taken the House of Commons by storm and prompted a vote about banning certain second jobs for MPs. CEO looks at what the scandal shows us about the loopholes in the European Parliament's own rules and procedures.

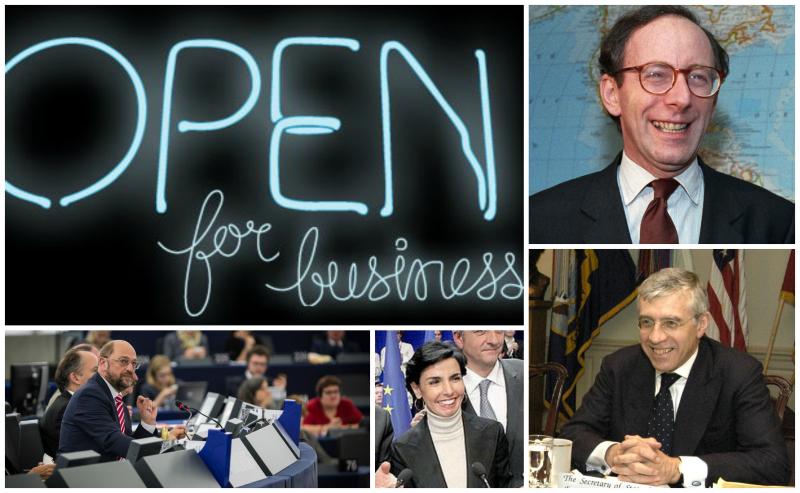

It has been unedifying to watch the current “cash for access” scandal erupt in the UK. Two very senior MPs, Malcolm Rifkind (Conservative) and Jack Straw (Labour) have been caught on camera bragging about the access to decision-makers that they could deliver for fee-paying clients. Both MPs are ex-foreign secretaries (the most senior foreign affairs position in the UK government); Rifkind was (until Tuesday) chairman of the important intelligence and security committee in the House of Commons; Straw had high hopes of being bumped up to the UK's second chamber (the unelected House of Lords) after the upcoming election.

In December 2014, reporters (from the Daily Telegraph and the TV programme Dispatches) contacted 12 UK MPs and were asked by email if they would be interested in joining a Chinese company’s advisory board. Half did not respond; one wanted to check it out further; and the others were interested, including Straw and Rifkind.

This scandal takes place almost four years to the day since the European Parliament's own “cash for amendments” scandal hit the headlines, when three MEPs were exposed as having agreed to table amendments to change an EU law in return for promised payments; two of the three ended up in jail as a result. This led to the development of the code of conduct for MEPs which has now been in place for three years.

As MEPs Richard Corbett and Sven Giegold embark upon initiatives to review the ethics rules in the European Parliament, what can MEPs learn from the latest UK scandal?

Who you know can earn you money ie. cash for access remains a real issue

Jack Straw boasted to the undercover reporters that he had changed the rules governing sugar production in Ukraine as well as separate sugar regulations at the European level in Brussels (although the European Commission has since disputed his version of events). Straw said:

“I’m well aware of the fact that I bring my name” and “I know everyone anyway, I’ve got their phone numbers.”

Meanwhile Malcolm Rifkind told the journalists:

“Well you see what I can do in London, I can see any ambassador that I wish to see. If I ask to see them, because of having been a foreign minister it is, it is almost automatic that they would do that and that provides access in a way that is, is useful.”

He also boasted about his high-level defence contacts and membership of an international panel of nuclear security experts.

It is a truth universally known that powerful politicians have extensive contact books and that some are not above using them for personal gain or to promote corporate interests. But yet our political institutions in the UK and the EU fail to take serious action to block such activity. This scandal reminds us that this is a real problem which needs tackling.

Transparency is important … but isn't enough

A repeated justification from both Straw and Rifkind has been that their outside work was all above board because it had been declared via the list of members' interests in the House of Commons. “We have to declare down to the last penny — which is slightly boring,” Jack Straw said. MEPs too are required to declare their outside earnings (albeit in unsatisfactory bandwidths, rather than precise sums).

Transparency means that information about politicians' outside interests is in the public domain and it can help to identify potential conflicts of interest. Yet transparency does not, in and of itself, stop conflicts of interest. In fact it is a peculiarity of the users' guide for the code of conduct for MEPs that it says:

“The Code of Conduct does not interdict conflicts of interests, but seeks to ensure that any actual or potential conflict of interest is declared promptly and transparently by a Member”.

This is a nonsensical state of affairs and the code needs to be overhauled to make 100 per cent clear that conflicts of interest will not be tolerated.

Furthermore, despite transparency about his additional income, Straw boasted that in terms of specific activities carried out, he preferred to operate “under the radar” via private lobbying rather than more publicly. In the UK there is no lobby register that would force Straw's paymasters, in this instance ED&F Man, to register and come clean about who they pay to lobby on their behalf; the incoming UK lobby register will only cover lobby consultancies rather than lobbying activities conducted by other organisations. At the EU level a more comprehensive lobby register does exist but it is not mandatory; ED&F Man is absent, despite clearly paying an MP to lobby on its behalf at the Commission. It is not known whether or not Straw declared who he was working for when he held his Commission meeting(s). A comprehensive, legally-binding lobby transparency register is the only way to go for both the UK and the EU.

Being elected means serving constituents not private paymasters

“You’d be surprised how much free time I have. I spend a lot of time reading, I spend a lot of time walking. I’m self-employed. So nobody pays me a salary”,

Rifkind told the undercover journalists; no doubt his constituents were also surprised to learn this.

The MP has since said he was “silly” to say that “nobody pays me a salary” considering that all UK MPs receive a healthy £67,000 a year (plus expenses). This compares favourably to the average UK wage of £26,500. Other MPs have protested that while Rifkind may not find the job of MP a full time one, they find themselves busy 6am-10pm weekdays carrying out their parliamentary and constituency duties.

But there are some additional and crucial issues here about whether or not paid, elected politicians should have second, third, fourth jobs... on the side. The leader of the UK Labour Party Ed Miliband has written to Prime Minister David Cameron to suggest limits on MPs’ additional income of a cap of 10 or 15 per cent of their parliamentary salaries; crucially he has also demanded a ban on MPs holding outside directorships and consultancies and Labour forced a House of Commons vote on this idea last night (25 February). The vote was ultimately lost but Labour has said that it will amend its own standing orders to ensure the ban applies to its candidates and MPs.

Labour's proposals are along the right lines. If a paid second job requires an MP to represent someone else's interests - consultancy, lobbying, legal representation, sitting on a board - it has the potential to interfere with the role of representing constituents and the public interest and these roles should be banned outright.

At the EU level, the MEP code of conduct is woefully quiet on the issue of second jobs and this is one of its greatest weaknesses. Transparency International's Integrity Watch project shows how many MEPs have substantial extra earnings, based on their declarations of interest. Top of the list is Guy Verhofstadt MEP (a former Belgian prime minister and current chair of the Liberal group in the parliament) who is a director of a shipping company and an investment company, among other additional jobs. According to his declaration he receives more that €15,000 a month on top of his salary; his attendance rate at the European Parliament is 67 per cent. In all, 10 MEPs earn more than €10,000 a month on the side; 16 earn between €5000 and €10,000; and 111 earn between €1000 and €5000 a month.

It is not just about when you are in office

Straw made clear that his discussions-cum-negotiations with the fake Chinese company were substantively about work he might do for them after leaving the House of Commons and elected office after the May 2015 election. “The implications are that I can do a lot more for you,” Straw said. “It’s better if I’m outside.” He said he would not take the advisory position if he were going to remain an MP.

There are no rules revolving door rules in the UK for MPs who leave office. UK ex-ministers are covered by the rather toothless Advisory Council on Business Appointments and Straw has said that he has checked his subsequent occupations with ACOBA.

In the European Parliament revolving door rules are similarly lacking. Recent cases of MEPs leaving office as profiled on CEO's RevolvingDoorWatch show that this is a cross-party problem and it needs urgent reform and oversight. From the Conservatives, we have seen Martin Callanan (ex member of the environment committee) offer consultancy services, including to Symphony Environmental Technologies; from Labour, ex-MEP Arlene McCarthy is now lobby firm Sovereign Strategy's deputy chair for European strategy; and from the Liberal Democrats, Sharon Bowles who was chairman of the influential economic and monetary affairs committee, is now a non-executive director at the London Stock Exchange.

If we want to stop MPs and MEPs from receiving private gain and boosting corporate interests based on their time in public office, revolving door rules need to be introduced, along the lines of cooling off periods or bans on accepting certain kinds of jobs, including lobby jobs.

Rules are important, but so is enforcement

The area of ethics, transparency and conflicts of interest is a subjective one and there will always be those who interpret rules to the letter, rather than in the spirit in which they were written. Straw and Rifkind deny that they have broken the ethics rules that exist for MPs.

There is also the matter of enforcement; one allegation against Straw is that he used his parliamentary office to host a meeting about possible private interest when that is against the rules. A more serious allegation is that his parliamentary assistant (paid for by public funds) helped out with Straw's consultancy work. Enforcement is absolutely key to sending the message to politicians that ethics rules are important and that if they breach them, they will face serious consequences.

At the European level, enforcement of the code of conduct has so far been woeful. Martin Schulz (president of the European Parliament) is ultimately responsible and has failed to take action on important cases. In November 2013 CEO complained to President Schulz about Louis Michel MEP after a Belgian TV programme revealed that he had submitted 229 amendments to the EU's Data Protection Directive, amendments which had been drafted by two industry lobby groups (VBO and Agora). The advisory committee on the code of conduct concluded that Michel had violated the code; Schulz decided there was no need for sanction.

In February 2014, Friends of the Earth Europe and CEO wrote to Schulz about Rachida Dati MEP following media coverage of possible consultancy links between Dati and the energy group GDF Suez which were not reflected in her declaration. The declaration only mentioned that she was a lawyer, but it did not provide any further details on the type of law practice, or the type of clients (individuals, companies or other organisations). Eight months later, a second letter was sent to Schulz, highlighting his lack of response and demanding a response. In November, Schulz replied stating that he had asked Dati for a clarification about her declaration of financial interest. Since then there has been no further communication.

So once again the challenge is set for political leaders in the UK and the EU: will you really get to grips with our elected politicians' potential and actual conflicts of interest and introduce the rules and enforcement necessary to tackle them? Ed Miliband has demanded tough and immediate action to tackle MPs' second jobs; will his fellow socialist Martin Schulz take similar action in the European Parliament?

To find out more about the 'cash for access' story in the UK, watch Channel 4's Dispatches programme which highlights the main allegations: http://www.channel4.com/programmes/dispatches/on-demand/60450-001