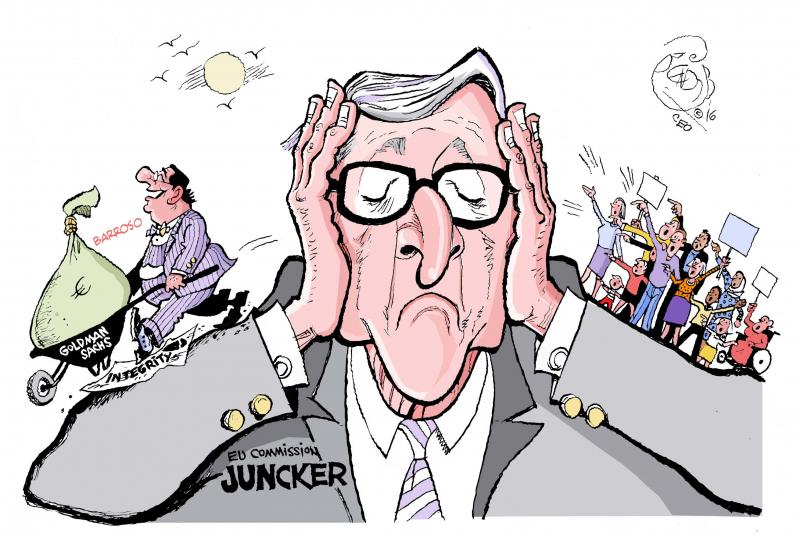

Juncker’s unremarkable reform of Commissioners’ ethics rules

It took president Juncker more than a year to propose new ethics rules for Commissioners after ex-President Barroso had shocked Europe with his new job at Goldman Sachs International. Hundreds of thousands of citizens, NGOs, the European Parliament and the EU Ombudsman had asked for ethics rules to be tightened and for the revolving door between the highest levels of the Commission and the business world to be closed. A year of inaction later, the Commission is now in a hurry to implement a lackluster reform that does not actually take into account citizens’ concerns.

In his latest State of the Union address President Juncker promised to reform ethics rules in the Commission and “strengthen the integrity requirements for Commissioners both during and after their mandate”.

This reform is an attempt to draw a line under the controversy after Barrosogate in July 2016. Following the Barroso scandal there were serious questions whether the code was fit for purpose. Even the European Ombudsman declared that “[i]t is not enough to say that no rules were broken without looking at the underlying spirit and intent of the relevant Treaty article and amending the Code to reflect precisely that.”

A stronger Code of Conduct with clear and effective ethics rules is urgently needed to prevent further scandals, but also to change the established institutional culture that views revolving doors roles with clear conflicts of interest as natural and legitimate steps in policy-makers’ careers.

Juncker’s initiative to reform the Code is welcome but do the proposed changes address the Commission’s revolving doors problem? The answer, in short, is no. (Our full analysis of the Commission’s proposal is available here).

”We don’t mind revolving doors, just wait a few months longer”.

The Commission’s cornerstone for preventing conflicts of interest is the notification period, the so-called ‘ccoling-off period’ of currently 18 months during which former Commissioners must notify and seek authorisation from the Commission to take up new roles once they have left office. The relatively short duration of this transition time aside, the policy is also riddled with loopholes, such as a too narrow an understanding of conflicts of interest and a very weak and vague ban on lobbying jobs.

Juncker’s proposal is to extend this period to two years for ex-commissioners and three for ex-presidents of the Commission. While an improvement, this is still below the three years requested by MEPs in the 2016 JURI report penned by MEP Pascal Durand, and amplified again this year in the AFCO report authored by MEP Sven Giegold. It is also below the three-year notification period demanded by the 63,000 petitioners who asked the Commission to block its revolving doors with big business.

This notification period also pales in comparison with the one in place, for example, in Canada, where former cabinet ministers are banned from lobbying roles for five years, and are also subjected to additional conditions.

President Juncker’s proposal is only a marginal extension and we have to ask: would a wait of six months more have made the new role of former Commissioner for the Digital Agenda, Neelie Kroes, at Uber and Salesforce, announced days after the 18 months notification period expired, more palatable?

We fear that Juncker’s proposal simply implies ‘we don’t mind revolving doors, but please wait a few months longer’.

A non-independent ‘independent ethics committee’

In anticipation of the State of the Union speech, president Juncker went on a charm offensive to promote his scheduled reform of the Commission’s internal ethics committee. At the time, Juncker’s promise to finally deliver an independent ethics committee instilled some hope in those following the problems related to revolving-door moves.

This new Independent Ethical Committee is to replace the current Ad-Hoc Ethics Committee (AHEC), a body made up of three members appointed by the Commission to provide internal advice on potential conflicts of interest arising from ex-commissioner’s new roles.

This ethics committee has increasingly moved to the centre of the Commission’s ethics discussions because it is the only body, beyond the College itself, with the responsibility to oversee the proper implementation of the Code of Conduct for Commissioners.

Yet several problems have been raised regarding its functioning, mostly relating to its lack of independence: it is too dependent on the Commission itself as it is not able to start its own inquiries or define the parameters of its investigations, and it can only advise rather than make decisions.

Take the example of Barrosogate: President Juncker only decided to forward the case to the ethics committee two months after his new role at Goldman Sachs International was announced, and even then he did so mostly in response to a wave of criticism from civil society and members of the European Parliament.

The committee found that Barroso had acted without the “considerate judgment one may expect from someone having held the high office he occupied for so many years”. Still, the opinion goes on to say that no action was needed.

The Committee arrived at this conclusion after reviewing merely one letter from ex-President Barroso to President Juncker, in which he stated that he would not be undertaking any lobbying activities on behalf of the bank. Barroso was never interviewed or even asked for documents to back this up. The Committee never even probed what Barroso meant when he said he would not lobby on behalf of Goldman Sachs International, even though this was a crucial point in its decision not to prosecute Barroso.

It is not surprising then, that within less than one year of that opinion, media have reported that Barroso has been back to Brussels to lobby sitting Commissioner for Jobs, Growth, Investment and Competitiveness, Jyrki Katainen.

Other problematic roles of Barroso’s ex-colleagues, including former Commissioner for Digital Agenda Neelie Kroes’ jobs at Uber and Salesforces, and former Trade Commission Karel De Gucht’s role at ArcelorMittal, were never even considered by the committee– because the Commission did not request its opinion.

In effect, this means that the Commission’s ethics system has relied on self-policing and limits ethical investigations to political will.

The Commission proposal to reform the Code of Conduct includes “creat[ing] an Independent Ethical Committee”. But despite the proposed change of name from “Ad-Hoc” to “Independent Ethics Committee”, the body's dependency, lack of powers and limited purpose remain largely unchanged.

For the ethics committee to be independent, it must be explicitly endowed with research and investigatory capacity to launch and conduct full assessments of whichever cases it deems appropriate. There should be an expectation that decisions from the committee are based on an assessment of all relevant documents - not just those submitted to the committee - and for investigations to include wider research into the proposed employer and role, where required.

Just waiting for the scandals to go away?

There are some upsides to the current Commission proposal, including the introduction of greater transparency of the committee’s decisions, the introduction of a fleshed-out definition of conflicts of interest and the clarification that lobbying is to be understood according to the definition in the EUTransparency Register.

But overall, the Commission has failed to truly take on the challenge. Instead it has concentrated on small tweaks to the current rules. As the many scandals that have plagued the Commission have shown, a stricter ethics system is indeed urgent, but a proper reform requires bigger steps than those proposed by the Commission has proposed.

Worse, the Code is set to be implemented in February 2018, which means the Commission is waiting only for a non-binding opinion from the European Parliament. It is disheartening that after so much public mobilisation on the topic, so many petitions, position papers, reports from the Parliament, and inquiries from the Ombudsman, the Commission seems determined to implement this proposal speedily, without consultation of outside voices or even waiting for the conclusions of the current Ombudsman inquiry into the functioning of the Ad-Hoc Ethics Committee.

The Commission appears to aim to just stop the discussion around revolving doors without genuinely addressing the problem head on. But if it doesn’t take more ambitious and stronger measures in its approach to dealing with the revolving door, more Barroso scandals will follow.

----------------

You can read our full analysis here. CEO supports an efficient reform which must include:

A longer notification period of at least three years for ex-commissioners and five for ex-presidents of the Commission.

An explicit and wide ban on lobbying EU Institutions.

Tighter wording around exceptions to prevent the creation of loopholes.

A truly independent Ethics Committee with the power to start its own enquiries, define its own investigatory tools, and power to implement its own conclusions, including a wider range of sanctions when faced with non-compliance.

Beyond revolving doors issues we support:

More detailed financial interest disclosure.

A procedure for addressing conflicts of interest that takes into consideration Commissioner’s role as members of the College of Commissioners.

Enshrining in the Code the commitment to ensure balance and representativeness in stakeholder engagement.