Biosafety in Danger

How industry, researchers and negotiators collaborate to undermine the UN Biodiversity Convention

Documents released to Corporate Europe Observatory following a Freedom of Information request reveal how pro-biotech lobby platform Public Research Regulation Initiative (PRRI) unites industry, researchers and regulators in ‘like-minded’ groups to manipulate crucial international biosafety talks under the UN Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD).

(Please view a print version here).

This discovery is all the more important because two crucial moments which may have a huge global impact on biosafety are to take place shortly. From 2 – 13 July 2018, experts from the 196 countries that have signed this international agreement will gather in Montreal to continue discussions on controversial technologies such as Synthetic Biology and so-called gene drives made through gene editing. And on 25 July 2018 the European Court of Justice (ECJ) will publish a ruling about the legal status of new genetic engineering techniques including gene editing.

Biotech developers are trying hard to avoid the food and environmental safety rules that govern GMOs being applied to their products from new genetic engineering techniques, like gene editing. But environmental groups, scientists and farmers are calling for strict regulation of these new techniques, and for careful consideration of the socio-economic impacts of these technologies.

Even though the UN CBD and its Protocols on Biosafety and on Access and Benefit Sharing of Genetic Resources, the Cartagena and Nagoya Protocols, have attracted far less attention from the international media than its climate counterpart the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC), from the very outset the CBD processes has been carefully followed by large numbers of corporate lobbyists, mostly from the biotechnology sector.

The Cartagena Protocol on Biosafety sets international rules to ensure the safe handling and transportation of genetically modified organisms (GMOs) or living modified organisms (LMOs), as they are known in the Protocol, with the aim of protecting biodiversity and human health. The Protocol also looks at socio-economic considerations arising from the impact of GMOs on biodiversity, especially with regard to its importance to indigenous and local communities. Biotech companies, researchers and the big exporting and importing countries of GM crops have a huge stake in these issues and thus work systematically to influence the CBD as it develops.

Several batches of emails released through freedom of information laws in Canada, the US and the Netherlands show how PRRI coordinated circles of industry, researchers and regulators through dedicated email lists covering the main topics of the CBD and Protocols. PRRI’s work in this area was diverse, including organising around CBD online consultations feeding into negotiations, holding face to face preparatory meetings, providing a ‘backup team’ to support delegates at official meetings and training groups of students to echo industry positions at lobby and side events.

Corporate interests represented in these circles include Bayer, Monsanto, Croplife International and the J. Craig Venter Institute (developer of the world’s first life form containing human-built synthetic DNA). The emails also reveal the engagement of a group of “like-minded” regulators from Canada, the Netherlands, Brazil, Honduras and the UK, amongst other countries.

Last December the ‘Gene Drive Files’ showed how the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation (BMGF) paid lobby firm Emerging Ag $1.6 million dollars to mobilise voices to influence a 2017 online CBD consultation on gene drives in order to counter international calls for a moratorium on this controversial technology.

The forthcoming technical talks in Montreal in July, and the following Conference of the Parties (COP) this December in Egypt will be the next decisive moments for the fate of crucial work on biosafety, which is needed to address challenges posed by fast-evolving genetic engineering techniques and applications.

About the documents released by the Dutch Ministry of Health under Freedom of Information requestThe files which inform the present article were released on 18 May 2018 by the Dutch Ministry of Health, Welfare and Sport following a Freedom of Information request directed to one of its officials by Corporate Europe Observatory. Parts of these documents were censored by the Ministry prior to their release: all the names of people involved were redacted, on “privacy” grounds, as well as parts of the content, claiming that disclosure would be “unreasonably disadvantageous” to the people involved because it concerned sensitive information on negotiation positions, and could lead to “reputational damage” and exposure. Other batches of files used for this article (the ‘Gene Drive Files’) were released by the Texas A&M University and the North Carolina State University in August and October 2017 following Freedom of Information requests by Edward Hammond/Third World Network, and by the Canadian Food Inspection Agency following a request from the ETC Group (a group which monitors the impact of emerging technologies and corporate strategies on biodiversity, agriculture and human rights) in 2016. The Gene Drive Files include emails that do reveal the names of people involved. |

What is at stake: UN biosafety guidance and rules on extreme genetic engineering

Gene editing - refers to a set of techniques like CRISPR-Cas and Talens. Most gene editing techniques use enzymes to "cut" parts of the genome. The genome then "repairs" itself. Gene drives - a gene editing application that enables genetic engineers to drive a single artificial trait through an entire population by ensuring that all of an organism’s offspring carry that trait. Gene drives can be used to eradicate entire populations. (Source: http://genedrivefiles.synbiowatch.org/) Synthetic Biology - also known as SynBio or Synthetic Genomics – this involves the design and construction of new biological parts, devices and systems that do not exist in the natural world. This could be done for instance by ‘writing’ new genetic code, or by redesigning existing biological systems to perform specific tasks. (Source: ETC Group) |

The documents show how the lobbyists’ interest – and their collaboration with ‘like-minded’ regulators - was focussed on two key strands of work undertaken within the CBD and the Cartagena Protocol: (1) the production of a Guidance document (referred to in short as a Guidance henceforth) on GMO risk assessment and (2) discussions on new and extreme genetic engineering techniques: Synthetic Biology or SynBio, gene editing and gene drives.

Angelika Hilbeck, of the Swiss Federal Institute of Technology and board member of the European Network of Scientists for Social and Environmental Responsibility (ENSSER), who is involved in scientific capacity building in the Cartagena processes, explains that the norms agreed at the UN level are consensual and are therefore minimum standards by default.

Many developing countries have continually asked for capacity building and tools to support them in conducting risk assessment in order to protect biodiversity and human health. Hilbeck estimates that the UN norms and debates are “critically important for the majority of countries around the world that have hardly any to no own scientific or institutional capacity” to evaluate GMOs on their own. “If these rules would not exist there would be zero accountability to its potential adverse effects”.1

As Third World Network (TWN), an organisation closely following these UN processes, has explained, the UN Guidance for risk assessment is a central pillar of the Protocol. An adequate, thorough and informed risk assessment is the key tool which supports countries to take decisions on whether or not to import GMOs.

However numerous attempts have been made to delay and derail the endorsement of the Guidance by countries with strong biotechnology and trade interests. These countries “have effectively blocked endorsement of the Guidance, and have continually insisted on having it reviewed and tested”, according to TWN.

This view is supported by Angelika Hilbeck, who reported in 2015 in the Journal of Health Education Research & Development that the GM risk assessment work done under the Cartagena Protocol had been under attack for a number of years by business-friendly delegations. “Statements by a handful of Parties in line with counseling non-Parties discrediting the scientific basis of the Guidance without any scientific justification could repeatedly block progress [..] with no sign of ever being willing to accept any Guidance document other than its abolishment”. These delegations seemed to be opposed to having any UN Guidance on biosafety in place, despite many believing it to be necessary to avoid negative impacts on biodiversity and food safety, and in spite of the fact that it is in any case a voluntary document that Parties are not obliged to use.

But things would get even worse. At the 2016 Conference of the Parties (CoP) in Cancún, the country delegations which opposed, obstructed and blocked the UN Guidance also helped to bring about the shut-down of the UN working group (the Ad Hoc Technical Expert Group, AHTEG in UN jargon) responsible for this Guidance, causing years of delay in future work on risk assessment.

This same working group (AHTEG) was also responsible for setting priorities for further guidance for special topics like SynBio. At the previous Conference of the Parties (COP) in 2014, it had been decided that an AHTEG on Synthetic Biology would be established to further discussions on the topic.

These discussions on SynBio also address a new and highly controversial application of new genetic engineering techniques: gene drives. Gene drives, as explained by the ETC Group, are designed to force a particular genetically engineered trait to spread through an entire wild population – potentially even causing deliberate extinctions.

Ahead of the Cancún conference in 2016, a call signed by over 160 organisations worldwide demanded a global moratorium on gene drives, as the new technology could pose “serious and potentially irreversible threats to biodiversity, as well as national sovereignty, peace and food security”.

PRRI: public researchers or industry interests?

Established in 2004, PRRI’s stated aim is to involve the public research sector in regulations on biotechnology, but as Corporate Europe Observatory reported in a 2008 briefing, it is striking that the group consistently advocates views that are distinctly in line with those of the biotech industry. The focus of the group has primarily been on UN biosafety processes (CBD, Cartagena Protocol and Nagoya Protocol), but it has also organised events with biotech lobby group EuropaBio at the EU level.

PRRI’s founder, Piet Van der Meer, previously worked as a Dutch official involved in negotiating the Biosafety Protocol and in UN biosafety training projects. However, in both roles he was criticised for his bias in favour of industry-friendly views. Van der Meer subsequently left his regulator role and founded the lobby group PRRI.

Since its foundation, PRRI initially received funding from industry, including CropLife International, Monsanto, the International Service for the Acquisition of Agribiotech Applications (ISAAA) and the Syngenta Foundation; and later from several governments and EU-funded projects. However, PRRI does not mention any funding sources beyond 2012 on its website, and has not responded to Corporate Europe Observatory’s enquiry in this regard.

Based in Belgium at the Flemish Biotechnology Institute (VIB), PRRI has consistently aimed to lobby for industry-friendly policy outcomes without being seen as explicitly representing industry (the “third voice strategy”). Over the years they have, for instance, promoted sterile “Terminator Seeds” and GM trees, and have opposed increased public rights to be involved in decision-making on GMOs, and more recently the Guidance on risk assessment.

Mixing regulators and the regulated

The files released to Corporate Europe Observatory expose PRRI’s lobby approach in some detail. For example, in one of the emails released by the Dutch government, Van der Meer gave a short recap of PRRI’s involvement in the UN biosafety negotiations over the years.2

Activities and tactics undertaken to influence the UN talks included interventions and side events to “counter misinformation”; “damage control” aimed at steering away from civil society calls for moratoriums on certain applications like terminator seeds or GM trees; encouraging other organisations to get registered to have “more voices expressing the same message”; and most recently the training and coordination of a large delegation of students to boost the number of pro-biotech voices.

Over the years, PRRI began to team up with other like-minded organisations. These included the corporate-backed ISAAA (financed by Monsanto and Croplife International amongst others) to organise regional preparatory meetings for Cartagena Protocol talks, Target Malaria (a Gates-backed project aiming to use gene drives to eradicate mosquitoes) and the Cornell Alliance for Science (a Gates-backed project for biotech promotion).

The documents show that PRRI has been running several “informal, like-minded”3 email groups on key issues which the CBD and Cartagena Protocol processes address, including environmental risk assessment, liability, and SynBio.

Participants in these groups include industry representatives, researchers and, strikingly, government officials. Introducing a Canadian official, Jim Louter, to a PRRI email group, Van der Meer boasted that “the participation of PRRI members has had quite an impact in COPs, MOPs and AHTEGs”.4

During UN talks, Van der Meer told Louter, the PRRI network provides regulators with the services of a “’backup team’ who can give immediate feedback through email, or search for articles while you sleep”.

Recipient list showing mix of industry and regulators.

Preparing for the Cancún conference in 2016

The Conference of the Parties of the UN CBD (‘COP13’) and the Cartagena Protocol in Cancún (‘COP-MOP8’) in 2016 was to be a decisive moment for the parties to these international agreements to agree on the endorsement of the risk assessment Guidance. Leading up to that, several online consultation rounds took place to inform COP-MOP8 decisions.

PRRI was organised and systematic in its approach to influencing these important international negotiations. Almost a year early, in January 2016, it began informing its informal group with logistical details about attending CBD meetings, saying it was essential that they attend “in good numbers of like-minded countries and organisations who can support each other.”5 In addition to the COP-MOP meetings, PRRI encouraged the group to also attend the intersessional technical expert meetings and online consultations, because of their key role preparing the UN talks.6

Regarding Cancún, PRRI mentioned their plan to get a delegation of international students to participate in the negotiations and side events. The student group called “Biotech students at the UN” would engage in “science communication efforts for COP-MOP with party delegates”.7

PRRI member Maria Mercedes Roca, at that time also an official member of the Honduran delegation, agreed that they should mobilise in order to avoid “the activist NGOs” being the only source of information for certain “undecided or silent” parties, especially “the small and least developed countries in Latin America and the Caribbean, Africa and South East Asia”.8

Teaming up with ISAAA, PRRI also engaged in regional preparatory meetings to facilitate the participation of “scientists and stakeholders” in the UN biosafety process.

Meeting the ‘like-minded’ in Washington DC

The attack on the Guidance on risk assessment was in part prepared at a five-day closed meeting convened by Karin Hokanson of the University of Minnesota, who is part of PRRI’s email groups, and held in February 2016 at the headquarters of the International Life Sciences Institute (ILSI) in Washington DC.9 ILSI is a global lobby platform for the combined biotech, pesticides and food industries with members including Monsanto, Mondelez, Cargill and McDonald’s (see Corporate Europe Observatory’s briefing on ILSI).

This meeting was organised specifically to “create some consensus” among a group of “like-minded” biosafety regulators about the Guidance on risk assessment.10 Officials listed as due to attend were from Argentina, Australia, Japan, Canada, Brazil, Colombia, Mexico, the Philippines and the USA (a non-party to the CBD and the Protocol). The Dutch representative Boet Glandorf is listed as representing the EU.

Paraguay and South Africa were on the ‘to be confirmed’ list, indicating that PRRI considered them among the “like-minded” as well. As we will see further on, a number of these countries later successfully blocked the Guidance and shut down the AHTEG itself at COP-MOP8 in Cancún later that year.

A representative of the European Food Safety Authority (EFSA) also took part in this meeting. This was in spite of the fact that the EFSA has been subject to strong criticisms by civil society and in the media regarding its lack of independence, and that it had in the past tried to ban strong links in particular between ILSI and its panel experts. EFSA responded to queries from Corporate Europe Observatory to confirm that Dr Yann Devos attended this meeting from EFSA, with all costs for travel and accommodation paid for by the agency.11

As the German NGO Testbiotech exposed, Yann Devos is the co-author of a 2018 scientific paper, together with a Syngenta employee and Karin Hokanson, on an issue which he was at the same time responsible for at the EFSA; he also sits on the Board of Directors of the International Society for Biosafety Research (ISBR), an organisation sponsored by Monsanto and Croplife among others, together with Monica Garcia-Alonso of Estel Consult.

Representatives of ILSI, PRRI, the US Department of Agriculture (USDA) and a consultancy firm (Estel Consult) were on the Steering Committee for the meeting. PRRI’s Piet van der Meer is listed as “PRRI/University of Ghent”, however the university told Corporate Europe Observatory that these activities were not carried out in his university role of Guest Professor.

A USDA grant to the University of Minnesota financed the meeting, illustrating how the US government, though a non-Party to the UN biodiversity agreements, still tries to influence their outcomes.12 The ILSI Research Foundation provided the meeting space and some organisational support.13

Just after the gathering in Washington DC, another CBD online consultation on risk assessment was launched. Van der Meer called on the PRRI group to take part: “participation in the online discussions is important, because then it is ‘on the record’”.14

Dutch official requests PRRI support for EU decision on UN Guidance

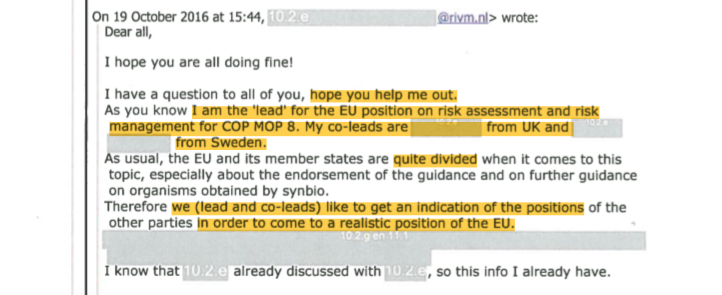

With the Cancún conference approaching, in October 2016 the EU member states were set to decide on the bloc’s endorsement of the UN Guidance on risk assessment and on the question of whether further guidance was needed for SynBio. Dutch official Boet Glandorf announced to PRRI’s email group that she had been appointed as the lead for the EU position, together with the UK and Sweden.

Glandorf wrote that the EU member states were “quite divided”, and asked the PRRI group whether they could provide her with indications of “positions from other Parties” on these two topics, and which Parties she could contact. “Having positions of other countries, based on good reasons, helps a lot”, she said.15

In another email Glandorf shared her own inventory of the opinions of EU experts with the PRRI group.16 PRRI’s Van der Meer said he was “reassured” that she was to lead the EU position and sent her the position of the Global Industry Coalition (GIC), the biotech industry’s lobby platform at the UN CBD processes. Van der Meer’s wife is a former key lobbyist for the Global Industry Coalition in the CBD. The coalition’s secretariat is hosted by Croplife International in Brussels. Neither of these organisations are registered in the EU Transparency Register.

Karin Hokanson of the University of Minnesota, who organised the Washington DC meeting, sent Glandorf intelligence on the positions of Brazil, Mexico, India and Japan, including contact details for delegates.

Hokanson said she would attend a CBD regional meeting in Africa, adding: “Keeping a low profile, but I will be there”. She hoped that the African countries would decide not to endorse the Guidance: “It would be HUGE if they would reject it, but I am not holding my breath.”17 She pointed out negotiators from Finland, Mexico, Moldova and China as “staunch supporters” of the Guidance. She ended by saying: “I am soooo hoping that the EU will somehow decide not to endorse it. It would make all the difference.”

Glandorf was also offered help by Monica Garcia-Alonso, a former Syngenta lobbyist for 18 years, who now runs the firm Estel Consult: “it looks like you have a difficult task ahead. I am happy to help you wherever you think I can”.

Glandorf was writing the EU position paper on the issues, and mentioned that she would incorporate advice from the PRRI group into it.18 While warning that as chair she could only facilitate the process,19 she would make sure her EU colleagues were aware that “there are a number of Parties who are not ready to endorse the Guidance and - more important - why this is the case”.20

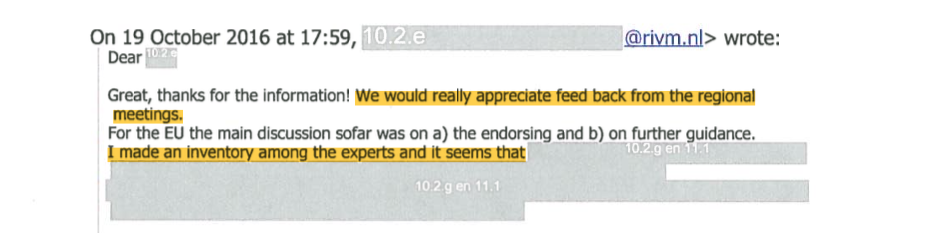

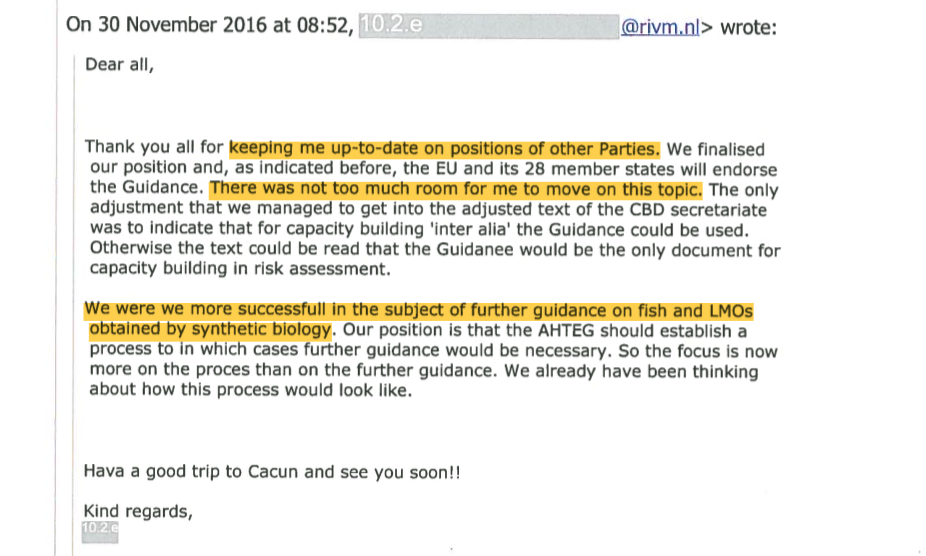

However in November 2016, after the EU Council discussions, Glandorf had to report back to the PRRI group that the EU did decide to endorse the UN Guidance,21 “even though I included in our draft position paper the very valid reasons of other Parties not to endorse”, adding that “There was not too much room for me to move on this topic.”22

She said the EU decision was motivated by a desire to “give a ‘positive’ signal” and that some member states thought the Guidance had improved. She added: “We are still collecting arguments why we are so positive :).” The PRRI group called the EU outcome “depressing”.23 However, Glandorf said she did manage to get the EU to withold support for the development of further guidance on GM fish and GMOs from SynBio – a not insignificant result.

Mapping out positions on UN Guidance

With COP-MOP8 in Cancún getting near, the PRRI email group continued to exchange intelligence regarding countries’ positions on the Guidance. Glandorf, for instance, provided a list of EU officials who would be participating in debates on risk assessment, from several EU countries (Austria, Slovenia, Finland, the UK, France, Belgium, Bulgaria and Sweden).24

Mercedes Roca chipped in that Mexico as the host country would probably endorse the Guidance to be “politically correct” and to maintain a “green image”.25 She explained that the Honduran position was not to endorse the Guidance, adding that this country’s position was influenced by the fact that risk assessors in Honduras had received training from the US Department of Agriculture (USDA) and from similar bodies from Argentina and Brazil – all large exporters of GM crops.26

She placed the Group of Latin America and the Caribbean countries in four categories: those that were ‘science-based’, ‘precautionary’, ‘mixed’, or ‘silent’. In general however, she said, developing countries “will adopt whatever they see coming from the CBD and CPB by default.” She concluded: “I feel much is at stake for this COP-MOP”.

Extreme Genetic Engineering: Synthetic Biology

Another issue on the table at Cancún was Synthetic Biology, often shortened to SynBio. A Bayer lobbyist shared with the PRRI email group that SynBio had been pushed onto the CBD agenda by “certain interest groups who are seeking the development of a new international regulatory framework that would not only deal with SynBio, but also with gene drives and gene-editing”.27

PRRI did not like the synthesis report of the SynBio discussions which was provided by the CBD Secretariat, as in their view it gave a “very unbalanced and very negative impression on the relationship between SynBio and Biodiversity”.28

The synthesis report states, for instance, that the risks and impacts of SynBio organisms should be assessed “prior to any introduction to the environment”, and that risks to human health and impacts on small scale farming and indigenous peoples should be taken into account. PRRI’s short comment on this provision was that “they’re trying to make [it] as onerous and time consuming as possible”.

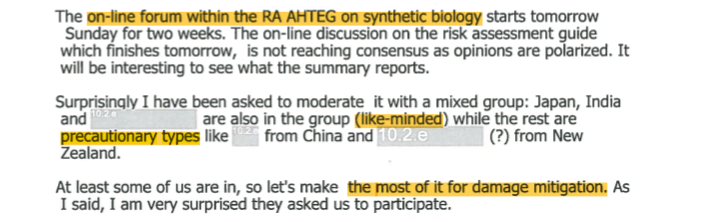

Maria Mercedes Roca was appointed as one of the moderators of a CBD online consultation on SynBio, together with other delegates. In her own words, some of these delegates were “like-minded” ones (from Japan and India), but others were “precautionary types” (from China and New Zealand).29

She expected “the precautionary side” to demand even more complex risk assessment guidelines than those that existed for GMOs, and that this would “very likely” extend to gene drives and gene editing.30

While she opposed these discussions even taking place, she observed that her undertaking a moderator role was “a small and rare opportunity to steer things in the right direction” before COP-MOP8. “At least some of us are in, so let’s make the most of it for damage mitigation.”31

Fighting off the call for a global moratorium on gene drives

The UN online consultation on SynBio also addressed gene drives. There is a paramount need to look at the risks of gene drives, because of the potential quick and irreversible spread of a new trait in complete populations.

Gene drives are designed to spread through ecosystems and eliminate populations and even species. However, as Helena Paul of Econexus explains, “they cannot reliably be confined to islands to eliminate pests as current proposals say. Moreover there are alternative approaches to addressing the problems these new techniques promise to solve and we should be exploring those as a priority”.32

Ahead of COP-MOP8 in Cancún, 160 environmental and social justice organisations world wide signed a call to the Convention for a global moratorium on the new technology, which they said posed “serious and potentially irreversible threats to biodiversity, as well as national sovereignty, peace and food security”.

In the past a similar moratorium was adopted by the UN on ‘Terminator Technology’ producing sterile seeds (also called ‘Genetic Use Restriction Technologies’, GURTs) a decision that was celebrated by farmers’ and environmental movements. PRRI’s statements on terminator seeds at the time were fully aligned with those of industry groups and the USA, all of whom were in favour of GURTs.

The PRRI group discussed how to prevent this call gaining support in the UN talks. The organisations ISAAA, Target Malaria and Island Conservation were listed as allies that would also get involved in the UN gene drive debate.33

A representative of Evolva, a Swiss biotech company, was of the opinion that they needed ““a show of courage” from somebody other than the industry or the scientific community”, whose views could not be easily “disparaged by NGOs without transparent self-incrimination”, and “cannot be written off by the [CBD] Secretariat, either.”

There was a clear worry, however, that side events looking critically at gene drives and SynBio would “greatly outnumber” more pro-biotech side events.34

Mercedes Roca proposed to “change the tune.. and use human emotion. Like the other side does.” With Mexico having been hit by the Zika virus, she added that “maybe many delegates will be worried about being bitten by mosquitoes with Zika, Dengue and Chikungunya (all “natural and organic” hahaha!)” and would therefore be more open to gene drives as a result. The PRRI student delegation was to be prepared for ‘changing the tune’ on gene drives, also “as the future parents of babies threatened by Zika”.35

The Gene Drive Files expose simultaneous Gates-funded lobby effortFiles released following Freedom of Information requests by researcher Edward Hammond to two universities in the US revealed how lobby firm Emerging Ag was paid $1.6 million dollars by the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation to try to skew the outcomes of CBD online consultations on SynBio and gene drives in favour of a less stringent approach. Emerging Ag covertly recruited over 60 seemingly independent scientists and officials to stack the online consultations with pro-biotech voices. The group of people involved in the coordination of this effort partly overlapped with the PRRI email group discussing the topic. The Emerging Ag operation involved three members of the previously mentioned UN expert group (AHTEG) on SynBio, two of whom represent institutions that received over $100 million dollars combined in U.S. military and philanthropic funds expressly to develop and test gene drive systems. The use of gene drives in bioweapons to drive extinctions has become a major security concern. Notes documenting a teleconference call of this network from June 2016 show that Emerging Ag and the J. Craig Venter Institute would approach the USDA to see if there were funding opportunities for PRRI to increase their ability to participate in online consultations. Following the release of the Gene Drive Files to the public, civil society organisations called on Dr. Cristiana Paşca Palmer, Executive Secretary of the Convention on Biological Diversity, to take urgent measures to address conflicts of interest in the CBD, its Protocols and subsidiary bodies. During the second week of UN meetings this July, the CBD Subsidiary Body on Implementation (SBI) meeting is expected to discuss the issue of conflicts of interest. |

Cancún 2016: shut down of risk assessment work

The Cancún conference was attended by a PRRI-registered delegation of around 50 and by 93 industry lobbyists registered through the Global Industry Coalition, Croplife International or the International Seed Federation. Tellingly, Piet van der Meer asked the group to make it a habit of copying Glandorf in on correspondence about countries’ positions on the various topics; “[She] is involved in coordinating the EU positions and any information you can share will help her in her task.”36

Van der Meer also mentioned that during the meetings in Cancún “communication experts of PRRI and the Cornell Alliance for Science will use Twitter and other social media” to report on what was happening. The Cornell Alliance for Science was set up with a $5.6 million grant from – once again - the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation with the specific aim to “depolarize the charged debate around agricultural biotechnology and genetically modified organisms (GMOs)”.

One day before the launch of the UN talks, PRRI and ISAAA jointly organised a preparatory meeting and a “pool-side/beach social event” for their delegates and lobbyists.37 Also invited to the social event were “like-minded” party delegations from countries like Mexico and Brazil, as well as “undecided” party delegations from Latin America, Africa and Asia.

The social event by the pool would enable the students to meet with delegates and make the latter feel “they are being mentors and coaches to the new generation. Most adults like that and show their generous side.”38 The Dutch official Boet Glandorf said she hoped to be able to skip formal meetings in order to attend the PRRI events39 and agreed to coach and mentor the PRRI students herself.40

However, at the side events inside the official process, the students made an odd impression on a number of attendees. ENSSER board member Angelika Hilbeck observed that the students “came across as carefully rehearsed and even drilled” but also showed “clear signs of distress”.41 Some students even had emotional breakdowns in side events.

After a few disruptive interventions, it was obvious that “they had the goal to derail the side events of groups who did not agree with their position on genetic engineering”, says Hilbeck. “They were encouraged in their disruptive behaviour by their professor Maria Mercedes Roca, the Honduran delegate. These tactics reveal a lack of respect of dissenting positions as well as democratic discourses and decision-making processes”.

The PRRI-team in Cancun. Source: ISAAA

Halfway through the negotiations TWN reported “strident opposition to the Guidance as well as to the continuation of the AHTEG to develop further guidance on specific topics of risk assessment”. The issue of risk assessment pitted developing countries requesting guidance and support against many developed countries and some developing countries with biotechnology and trade interests.

Brazil was part of the group leading the attack on the Guidance, complaining that the CBD Secretariat had published the Guidance as part of a so-called UN ‘technical series’ before it had been officially endorsed. While this is not an uncommon thing to do, Brazil accused the Secretariat of “violating their trust in the process”.

The tone of the discussions were “unusually discourteous and antagonistic for UN negotiations”, wrote TWN. Angelika Hilbeck makes a similar observation about the side events: "There was an abysmal decline of debate style, which was unprecedented and inappropriate to the United Nations."

“The use of emotion and aggression instead of rigorous science and a precautionary approach and the manipulation of enthusiastic students from the global south are simply not acceptable”, comments Helena Paul of Econexus. Christian Schwarzer of the Global Youth Biodiversity Network (GYBN), the official coordination platform for youth participation in the CBD, confirms that the members of GYBN's delegation too encountered "harassment and vocal attacks from PRRI-students, who said that our approach to uphold the precautionary principle would be detrimental to technological progress and human wellbeing".

"In general, our experience was that the PRRI students were extremely aggressive in their lobbying for SynBio and did not respect the code of conduct that is in place at UN conference.

An unusual development in these often tumultuous events saw the Honduran delegate and PRRI ally Maria Mercedes Roca de-badged (ie having her accreditation to participate in the conference withdrawn) after several serious shows of aggressive and bad personal behaviour – a very rare event in the history of the CBD.

As reported by TWN, African countries in particular, led by Mauritania and Uganda, “fought an uphill battle” to have the Guidance endorsed, as well as to continue the AHTEG in order for it to develop further specific guidance.

When the 8th Meeting of the Parties to the Cargagena Protocol came to a close after two weeks of often contested and difficult negotiations, the dramatic outcome was that there was no consensus for the endorsement of the Guidance, and not even for a continued mandate for the risk assessment working group (AHTEG): thus the group was dissolved.

According to Third World Network, the derailing of the risk assessment working group means that “any further specific risk assessment guidance will only be available, if at all, in another four years or more”. In order for the risk assessment work to reboot, a decision will have to be taken by the Parties to set up a new AHTEG working group. That battle will take place at the next COP-MOP in December 2018 in Egypt, and the discussion will begin at the meetings in July.

If this new working group decides to produce new guidance this will only be ready in 2020 at the earliest. In an area where technology keeps changing and developing at such a rapid pace, this is a major setback for the protection of biodiversity and food safety from potential adverse effects.

Next move: bring in the “innovation oriented farmers”

Not surprisingly, the feedback from PRRI and like-minded crowds post-Cancún was that there seemed to be “some light at the end of the tunnel” and that “it is important to keep the momentum.”42

The “signs of change” PRRI was happy to see included no decisions in favour of blanket bans on gene drives, more trouble for the UN Guidance on risk assessment with it not officially endorsed but only ‘taken note of’, and for the time being, no further guidance for new topics like SynBio.

PRRI analysed its own strengths while participating in Cancún as being the mobilisation of a diversity of organisations, and being numerous. “During the first 10 days, we had at any given moment around 50 scientists in the negotiations and side events, allowing us to have eyes and ears in every forum”.

PRRI and like-minded groups were kept up to date in real time via WhatsApp, and the collaboration with the Cornell Alliance for Science “allowed for a formidable boost in outreach through social media”.43

The presence of the students also had a “significant and positive impact” according to PRRI’s analysis, and Van der Meer indicated they should start preparing students, “the next generation of scientists and negotiators” for COP14MOP9 in Egypt in 2018. “With the characteristic energy and passion of youth, students are ready to get engaged”, and they “will ensure the continuation of the work we started”.44

Importantly, PRRI believed that the presence of young people could change the perception among delegates and show “that biotechnologies are not solely being developed by big corporations”.

The organisation also planned to continue to organise regional preparatory meetings “back to back with other regional meetings” jointly with ISAAA, as the experience of the COP-MOP8 had shown that “this kind of informal meetings is very useful”.45

In addition to the student-lobbyists, PRRI also planned to bring “a delegation of innovation oriented farmers to participate in COPMOP2018”. This would be done in association with ISAAA and the European ‘Farmers-Scientists Network’.46 This network is run by InnoPlanta, a German organisation which aims to promote the development of plant biotechnology and its acceptance in society.

In a presentation by InnoPlanta, the ‘Farmers-Scientists Network’ is presented as a network without formal members, that brings together ‘farmers in favour of GM crops’ and PRRI. (Interestingly, Fabio Niespolo, a former point of contact of this ‘Farmers-Scientists-Network’ has since been recruited by Emerging Ag – the lobby firm that played a key role in the Gene Drive Files.)

Finally PRRI said it was planning to reach out to environmental organisations that seem open to a “balanced approach toward biotechnology” and start a dialogue. One potential organisation named is the Environment Defense Fund.47 But PRRI indicated that it needed funding for these plans, noting that “we very much look forward to your suggestions for potential donors”.

Protecting biodiversity and democratic processes

In Montreal in July 2018, the CBD Subsidiary Body on Implementation (SBI) meeting will discuss the issue of conflicts of interest triggered by the Gene Drive Files. The CBD Secretariat has made proposals on conflicts of interest for this meeting, an issue that according to the Secretariat “has become important in the past few years in the context of improving the effectiveness of the work of technical expert groups”.

The Secretariat has taken an important and welcome step forward by proposing a more formal procedure for avoiding and managing conflicts of interest. Anyone nominated to be part an expert group “should be required to declare any interests […] that could constitute a real or potential conflict with respect to the expert’s responsibility as a member of the expert group”.

However, the proposals so far only address potential conflicts of interest in expert groups. Yet, as this article shows, the influence of industry-friendly groups such as PRRI and the Emerging Ag-network and their associated negotiators extends also to online discussions forums that are convened by the CBD and its Protocols. Due consideration should be extended to these processes as well, to ensure that at the very least, there is a procedure for disclosure of interest for participants of such online forums.

Many national governments also have their own codes of conduct for their staff. The Dutch code of conduct for government officials, for instance, states that citizens must be able to trust that the government is unbiased and that decisions are made on objective grounds. It also states the obvious fact that the public interest is paramount to public decision making. Corporate Europe Observatory believes that officials whose job is to regulate certain products in order to protect the environment and food safety should not be closely collaborating with companies that have a commercial stake in such products. Corporate Europe Observatory has asked the Dutch Ministry of Health whether they consider their code of conduct to have been breached in this case.

From Montreal to Sharm El-Sheikh

Having failed to persuade large parts of the world to adopt GMOs some twenty years ago, the promoters of the new genetic engineering techniques have increased and strengthened their efforts to break through this time, by insisting on de-regulation. At the international level the CBD with its Cartagena Protocol is the key convention for this battle. The EU, that following the ECJ ruling will be taking decisions on the legal status of gene editing and other new techniques, is bound by these international agreements and should ensure its internal positions are guided only by the public interest.

The released emails demonstrate how a small group of “like-minded” officials of a few countries teamed up with the biotech industry and its advocates in order to influence the outcome of UN biosafety talks. This is unacceptable. With the rapid pace of development of new genetic engineering techniques including SynBio and gene drives, it is crucially important to have internationally agreed binding rules to counter any potential damage to biodiversity or risk for food safety.

Developments in these fields are happening far faster than society’s capacity to assess the risks and the socio-economic impacts of these technologies. The Cartagena Protocol and the Convention are essential in examining these techniques closely and in ensuring that biological diversity as well as society, in particular Indigenous Peoples and local communities, are not adversely affected by the premature deployment of the new techniques.

1 Personal communication

2 Doc. 38, Dutch Ministry of Health

3 Doc. 4, Dutch Ministry of Health

4 Documents released by the Canadian Food Inspection Agency to ETC Group, p. 363

5 Doc. 1, Dutch Ministry of Health

6 Doc. 18, Dutch Ministry of Health

7 Doc. 30, Dutch Ministry of Health

8 Doc. 30, Dutch Ministry of Health

9 Documents released by the Canadian Food Inspection Agency to ETC Group, p. 600-601

10 Documents released by the Canadian Food Inspection Agency to ETC Group, p. 596

11 EFSA email to Corporate Europe Observatory, 26 June 2018

12 Documents released by the Canadian Food Inspection Agency to ETC Group, p. 600

13 Documents released by the Canadian Food Inspection Agency to ETC Group, p. 595

14 Doc. 4, Dutch Ministry of Health

15 Doc. 20, Dutch Ministry of Health

16 Doc. 20, Dutch Ministry of Health

17 Doc. 21, Dutch Ministry of Health

18 Doc. 23, Dutch Ministry of Health

19 Doc. 21, Dutch Ministry of Health

20 Doc. 24, Dutch Ministry of Health

21 Doc. 26, Dutch Ministry of Health

22 Doc. 33, Dutch Ministry of Health

23 Doc. 33, Dutch Ministry of Health

24 Doc. 27, Dutch Ministry of Health

25 Doc. 26, Dutch Ministry of Health

26 Doc. 26, Dutch Ministry of Health

27 Doc. 15, Dutch Ministry of Health

28 Doc. 1 and 1.1, Dutch Ministry of Health

29 Doc. 13, Dutch Ministry of Health

30 Doc. 15, Dutch Ministry of Health

31 Doc. 13, Dutch Ministry of Health

32 Personal communciation

33 Doc. 43.1, Dutch Ministry of Health

34 Doc. 28, Dutch Ministry of Health

35 Doc. 11, Dutch Ministry of Health

36 Doc. 31, Dutch Ministry of Health

37 Doc. 18 and 29, Dutch Ministry of Health

38 Doc. 29, Dutch Ministry of Health

39 Doc. 35, Dutch Ministry of Health

40 Doc. 32, Dutch Ministry of Health

41 Personal communication

42 Doc. 38, Dutch Ministry of Health

43 Doc. 38, Dutch Ministry of Health

44 Doc. 38, Dutch Ministry of Health

45 Doc. 38, Dutch Ministry of Health

46 Doc. 43.1, Dutch Ministry of Health

47 Doc. 43.1, Dutch Ministry of Health