Financial regulators and the private sector: permanent revolving door at DG FISMA

Yiorgos Vassalos and Corporate Europe Observatory

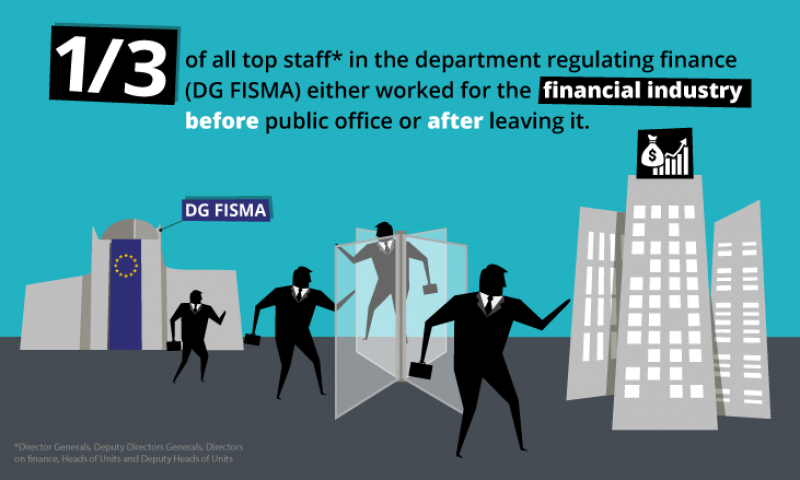

The Directorate-General responsible for banking and financial regulation at the European Commission, DG FISMA, has a revolving door problem. One third of the people who occupied top positions in the Directorate‑General for Financial Stability, Financial Services and Capital Markets Union1 during the period 2008-2017 - following the onset of the financial crisis - either came from the financial industry or went there after their time at the Commission.

New research into the career paths of DG FISMA’s top officials combines findings by PhD candidate Yiorgos Vassalos2 with updated Corporate Europe Observatory research to also reveal:

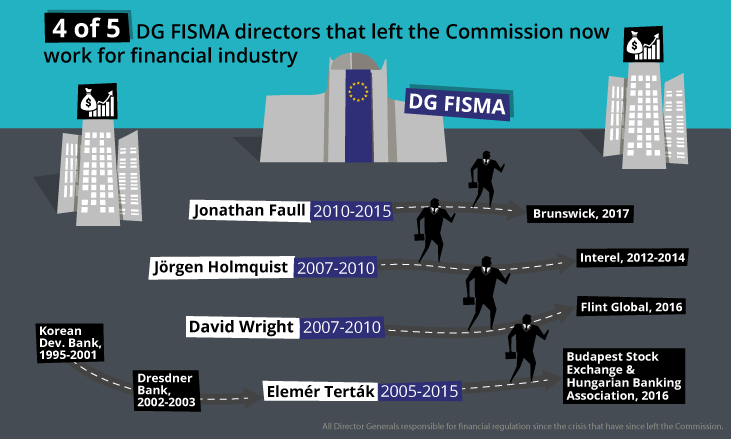

Out of the five former directors between 2008-2017 who have now quit the Commission, four went to work for companies they once oversaw or lobby firms that represent them.

Out of the three heads of unit who worked in the financial regulation departments of the Commission between 2008 and 2017 and have now left the Commission, one went on to work for the financial industry.

Six out of a total of twenty-seven heads of units and seven out of a total of twenty-two deputy heads of units in this period have worked in the past for the financial industry.

Two out of three Commissioners responsible for finance between 2008 and 2017 went to work for financial interests after the end of their mandate.

Research by the ALTER-EU coalition has shown that 92 per cent of DG FISMA’s meetings are with representatives of corporate interests, the vast majority of which represent financial companies. Only 8 per cent of meetings with non-government actors are with non-corporate actors such as unions, NGOs, academia etc. DG FISMA has so far failed to strike a balance in consulting with all types of interests in order to draft financial regulation for the sake of the public interest.

Reliance on industry’s expertise is also demonstrated by the composition of DG FISMA’s expert groups3 and by the fact that contributions from financial lobbies tend to dominate in most public consultations organised by the Commission on finance, making up about two thirds of all responses.

But the structural revolving door exposed in this article points to a problem of regulators being dependent on those they regulate. This goes far deeper than a mere reliance on the industry’s expertise: the official mission of DG FISMA’s top leaders to represent the public interest on finance could enter into conflict with their personal career prospects;4 when four out of five top directors end their career in the private financial sector, it is not a stretch to say that directors may well have this next step in their careers in the back of their minds while still in public office. And if this is the case, we must ask the question: could this incite them to promote window-dressing policies, rather than risk any measure that might upset their potential future employers?

Furthermore, conflicts of interest can occur when after leaving office, former public officials carry with them the insider influence, access, and know-how that can be used to unduly benefit their new employers.

The independence of policy-making is equally threatened when public officials are hired directly from the industry that is to be regulated. When people move from big banks and other financial lobbies to the Commission, it can be unclear whether they now serve the interests of the public according to their mandate, or whether pursuing their own career objectives prevails (for example by going back to the private sector in a higher position at some later point).

Our revolving door research points to a cultural bias: people who are very close to the private financial sector, having worked for years in it, tend to think of solutions more amenable to the private sector, even when these do not necessarily constitute the best option for the majority of economically active citizens who footed the bill of the bailouts and suffered austerity measures. Officials who find it natural to move between the role of the regulator and the regulated, may see little or no difference of perspective or interest between them. According to a working paper of the research department of the Dutch Central Bank, “social identification [of regulators] with the financial sector can be expected to thwart supervisors’ independence from the industry thereby – perhaps inadvertently – favouring financial sector’s vested interests and hampering supervisors’ responsibility to serve the public interest”.5

In contrast, very few DG FISMA officials have work experience in non-financial companies, academia, NGOs, or unions which makes this “social identification” with finance even stronger, since officials can ‘walk in the shoes’ of the financial sector but not of other points of view in society. A recent study covering the professional background of central bankers from OECD countries between 1973 and 2005, shows that those that had worked for the financial industry, de-regulated significantly more than those with different professional backgrounds.6

Ultimately, this situation fails to address the concern recently expressed by the European Ombudsman that “it is important to demonstrate to the public that there is a clear separation between the… supervisor and the finance industry”.

Four of the five directors that left the DG FISMA took up jobs in the financial industry

The career trajectories of twelve Director-Generals, Deputy Director-Generals, and Directors charged with financial regulation between 2008 and 2017 are listed in Table 1. Note that up to 2014, they led the Commission’s legislative, regulatory, and other work on financial regulation heading the relevant directions of DG Internal Market, DG MARKT. In 2014, these directions were separated from the other services’ sectors to form a special DG on financial regulation, DG FISMA7.

Table 1 – Director-generals, Deputy Director-generals and Directors on finance 2008-2017

Name | Period | Position | Industry job before | Industry job after | |

1 | Jonathan Faull | 2010-2015 | Director-General | - | Brunswick, 2017 |

2 | Jörgen Holmquist | 2007-2010 | Director-General | - | Interel, 2012-2014 |

3 | David Wright | 2007-2010 | Deputy Director-General | - | Flint Global, 2016 |

4 | Elemér Terták | 2005-2010 2010-2015 | Director H, Principal advisor to Dir.-Gen. | Dresdner Bank, 2002-2003 Korean Dev. Bank, 1995-2001 | Budapest Stock Exchange & Hungarian Banking Association, 2016 |

5 | Emil Paulis | 2008-2014 | Director G | Clifford Chance 1978-1982 | - |

Directors who haven’t yet left the Commission | |||||

6 | Nadia Calviño | 2010-2014 | Deputy Director-General | Director-General in DG BUDG | |

7 | Pierre Delsaux | 2007-2011 | Director F | Deputy Director-General in DG GROW | |

8 | Ugo Bassi | 2012-2015 2015 to date | Director F/B Director C | Still in DG FISMA | |

9 | Mario Nava | 2013-2015 2015 to date | Director H/D Director C | ||

10 | Martin Merlin | 2014-2015 2015 to date | Director G/C Director D | ||

11 | Olivier Guersent | 2014-2015 2015 to date | Deputy Director-General Director-General | ||

12 | John Berrigan | 2014-2015 2015 to date | Director E Deputy Director-General | ||

Four out of the five former directors from 2008 onwards who have now quit the Commission went to work for the financial industry: consultancies working for financial giants, stock markets, and banks. From the eight remaining in the Commission, six still work in DG FISMA, while two have become Director-Generals in other DGs.

After quitting DG FISMA in 2015 but before retiring from the Commission, Jonathan Faull took the lead in the Commission’s task force on negotiating a package of reforms aimed at convincing British voters to stay in the EU. When this failed, he announced he would quit the Commission and said: “there are things I still want to do”. In 2017 he became the full-time “Chair of European public affairs” of lobby consultancy Brunswick in Brussels. Brunswick claims to be working for “many of the world’s largest financial services companies” and is registered as a law firm in the Commission’s lobby register. Royal Bank of Scotland, Bank of America, InterContinental Exchange, Paypal, and the US asset management company Federated Investors are listed among its clients.

Faull also joined the advisory board of the think tank Centre for European Reform (CER) which is funded among others by American Express, Deutsche Bank, Barclays, Goldman Sachs, JP Morgan, and Lloyds. In the period between October 2016 and May 2017, CER had more meetings than any other (apart from major lobby group BusinesssEurope) with the Commission’s Brexit task force that Faull used to lead. CER has separately told Corporate Europe Observatory: “We have not and would not try to influence the Commission to act in ways that would benefit our sponsors”. Faull was not present in any of these meetings.

Jörgen Holmquist and David Wright quit DG FISMA in 2010 to join the Commission’s task force monitoring the implementation of the Troika’s austerity memorandum for Greece.8 They stayed there up to 2012. Then, Wright continued his financial regulator career at the international level, becoming the secretary of the International Organisation of Securities Commissions (IOSCO).

Wright quit IOSCO in 2016 to integrate lobby consultancy Flint Global in order to advise “financial services sector clients on European and global regulatory developments and Brexit”. Flint’s biggest Brussels client is the giant asset manager Fidelity that has been or still is a major shareholder in stock exchanges such as Euronext9 and Deutsche Börse.10

Holmquist went to lobby consultancy Interel European Affairs where he stayed up until his death in 2014. Interel has a financial services department working for clients such the Association of British Insurers, “worldwide stock exchanges”, and “multinational financial services groups”.

During his career Elemér Terták has gone five times through the revolving door between public and private financial sector. He joined the Commission directly as a Director in 2005 after being Permanent Secretary of State in the Hungarian Ministry of Finance and after his retirement he joined the boards of the Budapest Stock Exchange and the Hungarian Banking Association.

Emil Paulis is the only Commission Director on financial regulation in the period 2008-2017 who has now left the Commission and who didn’t move into a job which involves working for the financial industry or lobby groups working on their behalf.

The fact that four out of the five former DGs who have left the Commission since the financial crisis of 2008 have gone into the finance industry or related sectors isn’t reassuring. These were the pilots of EU financial reform in the aftermath of the burst of the biggest financial bubble since 1929. The very limited scope of the financial reform in the EU could be related to the shared culture and excessive proximity between DG FISMA directors and the financial institutions they were meant to regulate, a pattern made visible in their professional choices after leaving public office.

One of three heads of unit that left the Commission now works for financial industry

The revolving doors problem isn’t limited to directors. In the post-crisis period of 2008 to 2017, 27 Heads of Units served in DG FISMA and the financial regulation units of DG MARKT.11 Three out of 27 have now left the Commission. One, Miguel de la Mano went to Compass Lexecon, a law firm subsidiary of the second biggest lobby consultancy in Brussels, FTI Consulting which has a specialism in financial regulation.

FTI Consulting proudly declares having “former policy makers and regulators” among its financial lobbyists. Deutsche Börse, Bank of New York Mellon, Vanguard, Citadel, Mastercard and the Managed Funds Association are among its clients. It is unclear if Compass Lexecon’s clients are included in FTI’s EU lobby register entry but it seems clear that Compass Lexecon provides services beyond legal representation. According to its website, the Europe team “offers independent economic analysis and advice to clients engaged in legal and regulatory proceedings” including “regulatory review”.

Table 2 – Heads of financial regulation Units who have left the Commission

Name | Period | Unit | Post-Commission job(s) | |

1 | 2012-2015 | G1/B2 – Financial Analysis | Compass Lexecon (FTI) | |

2 | Karel Van Hulle12 | 2004-2013 | H2 – Insurance and Pensions | Goethe University, 2014 Public Interest Oversight Board (POB), 2016 Bermuda Monetary Authority, 2016 |

3 | 2009-2014 | F1 – Free Movement of Capital | Saarland University |

The other two cases, Van Hulle and Reinbothe, demonstrate the alternatives to jobs in financial interest representation13 such as academia, professional organisations and other public regulators that need their expertise. In contrast to a corporate lobby job, Van Hulle went to work for POB, a body attached to a professional organisation, the International Federation of Accountants.

Of the 30 individuals who either went to the Commission after working in the private sector or vice versa covered in this article,14 only three involved roles that did not represent big financial firms: Reinbothe who went to academia, Van Hulle who went to POB and Deputy Head of Unit Jennifer Robertson who worked for Εuropean Savings Banks Group.

6 of 27 Heads of Unit went from regulated to regulator

A further 6 of the 27 Heads of Units of the period are still in the Commission but have worked for the financial industry in the past.

Table 3 - Heads of financial regulation Units still in the Commission with past experience in the financial industry

Name | Year of entry in the Commission | Head of Unit | Past industry job | |

1 | Felicia Stanescu15 | 2010 | O1 -Policy coordination, 2017 | KPMG, 1995-1999 ABN-AMRO, 1999-2008 BNP-Paribas, 2008-2010 |

2 | Arvind Wadhera | 2005 | H1 – Banking conglomerates,2008 F4 –Audit, 2010 | BNP-Paribas, 2000-2005 |

3 | 1991 | E1 – EU/Euro area fin. system, 2015 | Hypo-Bank Merrill-Lynch | |

4 | 1986 | E2 – National fin. systems, 2014 | Kreditebank (KBC), 1984 – 1986 | |

5 | 1994 | B2 – Financial Analysis, 2016 | Unknown company in private risk management | |

6 | 1994 | H1 – Banking conglomerates,2014 | Center for European Policy Studies (CEPS)16 |

In 2005, Director of Corporate Finance in BNP Paribas Arvind Wadhera became deputy Head of DG MARKT’s Unit on banking and financial conglomerates. His résumé mentions being “the sole representative of DG MARKT in the Crisis Co-ordination cell, where he worked directly on 150 bailouts of banks”.

Thus Wadhera moved from one of the biggest European banks to being part of the public authorities’ coordination of the largest injection of taxpayers’ money into banks in history. His former employer, BNP Paribas, was perhaps the bank that profited more than any other from these bailouts since it consolidated its operation in many countries. From fourth or fifth largest bank in Europe, it became first or second.

7 of 22 Deputy Heads of Unit went from regulated to regulator

None of the 22 Deputy Heads of Unit who served between 2008 and 2017 have quit the Commission yet. Seven of them have had professional experiences working for the interests of big financial companies before joining the Commission.

Table 4 – Deputy Heads of financial regulation Units still in the Commission with past experience in the financial industry

Name | Year of entry in the Commission | Deputy Head of Unit | Past industry job | |

1 | Emiliano Tornese17 | 2009 | E4 – Banking resolution, 2015 | Davis Polk & Wardwell LLP18 2007-2008 |

2 | Valérie Ledure19 | 2007 | B3 – Accounting & financial reporting, 2014 | ING 2000-2007 Swift, 1999-2000 |

3 | Mattias Levin20 | 2005 | D2 – Banking conglomerates, 2016 | Center for European Policy Studies & European Capital Markets Institute 2000-2004 |

4 | Philippe Todd21 | 2004 | G3 – Securities Markets, 2012 C1 – Capital Markets Union,2015 | Hill & Knowlton22 1997-2000 |

5 | Dominique Thienpont23 | 1999 | D2 – Banking conglomerates, 2010 | KPMG 1992-1999 |

6 | 1990 | H3 – Retail & consumer policy, 2010 | “auditing and investment banking24” 1985-1990 | |

7 | 2004 | G2 – Financial market infrastructure, 2012 | European Savings Banks Group, 1999-2004 |

DG FISMA Revolving doors also present in lower levels

The revolving doors phenomenon is not restricted to a few dozen top DG FISMA officials. Around 130 policy officers25 are currently in post (of a total 300-350 personnel) and for the period 2008-2017 there are several more who have left. However, exhaustive research on all of them is difficult and remains incomplete. Anecdotal cases like the six listed in tables 5 and 6 below nonetheless indicate that the revolving door is a concern throughout DG FISMA. This includes lower level officials who make substantial contributions to the drafting of legislation and regulatory measures.

Table 5 – Anecdotal cases of policy officers coming from the financial industry

Name | Year of entry in the Commission | Past public sector jobs | Past industry job | |

1 | Sébastien Bagot26 | 2016 | Autorité des Marchés Financiers 2010-2016 | Lehman Brothers 2005-2008 PWC 2008, Nomura 2008-2010 |

2 | Tommy De Temmerman27 | 2016 | Single Resolution Board, 2015-2016 | Bank New York Mellon 2006-2008, Dexia/Belfius 2008-2015 |

3 | Valeria Miceli28 | 2016 | Professor of financial economics in Università Cattolica del Sacro Cuore, 2006 | Anima 2014-2016, Ernst&Young 1998-2000 |

Sebastien Bagot was working for Lehman Brothers, the bank at the heart of the 2008 financial crisis, as a derivatives trader when the bank collapsed (largely due to its exposure on derivatives markets). Bagot found shelter for few months in PriceWaterhouseCoopers. Then he continued his trader career for two more years in Japanese holding Nomura before he dedicated himself to financial regulation.

Meanwhile Tommy De Temmerman experienced the collapse of Franco-Belgian bank Dexia from within. Valeria Miceli spent two years working for Milanese asset manager Anima.

Table 6 - Anecdotal cases of policy officers who went into the financial industry

Name | Past job(s) | Years in the Commission | Post-Commission job(s) | |

1 | Czech Securities Commission 2003-2004 | 2005-2010 | Alternative Investment Management Association (AIMA) 2010 onwards, Alternative Credit Council (ACC) 2015 onwards. | |

2 | Sabine Schönangerer29 | State Street 2004-2009, Financial Services and Markets Authority 2009-2012, Euro Working Group 2012-2014 | 2014-2017 | Nordea 2017 |

3 | HM Treasury, 2001-2009 | 2009-2011 as seconded expert 2014-2017 in Hill’s Cabinet | Deutsche Bank 2011-2014, Financial Conduct Authority 2017 |

As a DG MARKT policy officer, Jiří Król worked from 2005 to 2007 on the finalisation of MiFID 1 legislation30 organising consultations with the financial industry. From 2007 to 2009 he was seconded from the Commission to the Czech Presidency which he represented in the first institutional discussions on regulating hedge funds. The following year he was hired by the main hedge fund lobby group, the Alternative Investment Management Association, of which he is today the deputy Chief Executive Officer while running the Alternative Credit Council too.

Sabine Schönangerer started her career at the department of investment fund sales to institutional clients in asset management giant State Street. She moved to a regulator’s role in 2009 when she integrated the Belgian Financial Services and Markets Authority (FSMA). In 2012 she joined the Economic and Financial Committee’s secretariat where she worked on the preparation of Eurogroup meetings within the Euro Working Group and in ad hoc working parties on the single surveillance and resolution mechanisms. As a policy officer in DG FISMA she worked a lot on MiFID 2 and represented the Commission in working groups of the European Securities and Markets Authority (ESMA). In 2017 Schönangerer moved back to the private sector in order to help Swedish bank Nordea to comply with the very legislation she had contributed to drafting (MiFID 2) that came into force on 3 January 2018.

In 2009 Lee Foulger was seconded from British ministry of finance (the Treasury) to DG MARKT where he worked on bank resolution, shadow banking, and the architecture of the new EU financial supervision authorities (like ESMA) that were to be created as a reaction to the crisis. In 2011, he was recruited by Deutsche Bank to become its chief lobbyist on securities markets’ regulation.

When Jonathan Hill became EU Commissioner for finance he put Foulger in his cabinet to deal with these same questions overseeing the DG FISMA’s work and negotiating with Council and Parliament in trilogues. When Hill resigned following the Brexit referendum, Foulger and his deputy on financial markets, Mette Grolleman ensured the transition of their portfolio to Commissioner Valdis Dombrovskis and then left the Commission in 2017.

Foulger went to the British regulator FCA and Grolleman joined Brussels biggest lobby consultancy, Fleishman-Hillard which has big banks (JP Morgan, Morgan Stanley, ING, Banco Santander, Crédit Suisse, Danske Bank, Erste Bank) and their main lobby groups for financial markets (AFME, ISDA) among its clients, as well as asset managers (Blackrock, Capital Group), platforms of financial transactions (BATS, Tradeweb), and other financial lobbies such as PCS and Markit.

Inside knowledge of administrative and political dynamics within the Commission is of paramount importance to financial lobbies that need to know how to exploit them in order to be effective. It is eminently resourceful for Deutsche Bank to hire a former DG MARKT official like Foulger and for Fleishman to hire a former Commissioner’s cabinet member like Grolleman.

The other way around, it was only natural for Commissioner Hill – a former financial lobbyist who is now once again working as a senior adviser to a law firm that lobbies on behalf of financial industry clients – to hire Foulger, a former Deutsche Bank lobbyist, to play a leading role in his Capital Markets Union project aiming to get rid many of the few restrictive measures that were adopted as a reaction to the crisis.

Commissioners’ revolving doors set the example

Two of the three Commissioners who had the political responsibility for financial regulation in the post-crisis period 2008-2017 also went to work for big finance after their mandates. Up to 2007 then-Commissioner for internal market and services Charlie McCreevy concluded the first wave of financial Europeanisation and liberalisation that allowed the rampant growth of securitised and derivative financial products. This growth was part of what made the financial bubble so huge and the consequences of its bursting so widespread. In 2008, he approved hundreds of billions of euros of state aid to save collapsing banks. In 2009, he actually did name massive lobbying from banks as one of the causes of the crisis, as well as law-makers’ excessive attention to such lobbying (including his own).31 However ALTER-EU’s report from 2009 showed that he didn’t seem to tackle the problem, for instance leaving the composition of the Commission’s expert groups in finance (229 of 246 non-government members represented financial companies) unchanged.32

In 2010 he became the first former Commissioner in history to be given the red light by the Commission over his attempted revolving door move to a new London bank called NBNK he aimed at creating, together with the Chair of Lloyds and former Chair of Morgan Stanley through acquisitions. One week after the reporting period was over he joined the derivatives trading unit of Bank New York Mellon, where he stayed for one year. He also joined other financial firms such as Sentenial Ltd, World Spreads and Celsius Funds plc.

McCreevy’s successor Michel Barnier (2010-2014) reduced financial industry’s participation in the relevant Commission expert groups and didn’t go through the revolving doors after his mandate.

After him, came Jonathan Hill, a long term lobbyist (Lowe Bell 1989-1991, Bell Pottinger 1994-1998) who has switched roles five times between public and private sector. In 1998 he co-founded London lobby consultancy Quiller whose client list in 2010 was mostly made up of financial players such as HSBC and Bank of America. In 2010 Hill moved from lobbying to politics, becoming a British Junior Minister. A few months after his resignation as EU Commissioner he joined Freshfields, a law firm that lobbies EU Institutions for Lloyds, London Stock Exchange, and the Futures Industry Association, among others.

Additionally, there is former President of the Commission Jose Manuel Barroso’s highly controversial move to Goldman Sachs, who has since been highly criticised for having meetings with sitting commissioners to discuss EU policies that were logged as lobby meetings

The number of revolving door moves from ex-commissioners to the financial industry extends even beyond those that had direct responsibility over financial policy, including Neelie Kroes joining Bank of America Merryl Lynch; Karel De Gucht, Merit Capital; Gunter Verheugen, Royal Bank of Scotland and Fleishman-Hillard; Benita Ferrero-Waldner, Munich Re (insurance); and Meglena Kuneva, BNP Paribas.

These cases indicate the revolving door problem exists at the level of the highest political leadership too, which gives a clear signal to DG FISMA’s staff that the revolving door is a normal part of their careers, if not a characteristic of the most successful and high-level careers.

Ethics rules leave the revolving doors’ culture intact

The Commission has rules in place meant to mitigate potential conflicts of interest, but these have not stemmed the tide of cases where public officials either left the Commission and directly took new roles in the private sector, or vice-versa.

Commission officials are bound by a two year period during which they must notify the Commission of any new role they intend to take up, paid or otherwise. Those roles are scanned for activities that could create a conflict of interest with the work areas that officials were responsible for during the previous three years. If that is found to be the case, these roles can be rejected or authorized under certain conditions. Senior officials can be further bound by a lobby ban for 12 months but only towards their former colleagues and institutions and only covering matters for which they were responsible.

Commissioners, on the other hand, were bound by a 12-month notification period in 2008 extended twice since then, first to 18 and recently to 24 months, as a result of the public outrage over 6 out of 13 outgoing Commissioners going through the revolving door in 2010 and Barroso taking up a job at Goldman Sachs International in 2016. Commissioners are also subject to a lobby ban in areas for which they had been responsible. Yet the changes appear to be insuficient since they don’t deal with the loopholes in effective monitoring during the transition period (full analysis here). A step to quieten down criticism, while maintaining a culture that sees the transition from regulator to regulated as a natural career progression.

While improvements in rules are welcome, they are too vaguely worded and, worse, poorly implemented to actually mitigate the problem. Implementation of the rules is poor in part because it is conducted and based on assessments made by the applicants’ previous colleagues, which tend to give more weight to the officials ‘right to work’ rather than the duty to prevent conflicts of interest.

Take for instance the cases of Jonathan Faull, the former Director of DG FISMA and then leader of the Commission’s Brexit taskforce, and Jonathan Hill, former Commissioner. Both were allowed to work with lobby firms that represent the financial industry, which they were previously regulating, within months of leaving public office.

Just last month the European Ombudsman has issed a scathing critique of the way that the Commission handled former president Barroso’s employment at Goldman Sachs and warned of “ systemic issues concerning the Commission’s handling of such cases”. There is also another European Ombudsman follow-up inquiry dealing with the implementation of ethics rules for former officials.

Many cases involving senior officials and commissioners listed in this research have been subject to evaluation and even to restrictions applied by the Commission. During the period studied, the revolving doors rules have been tightened for both commissioners and staff. Our purpose in this article has not been to review the specifics of the Commission’s decisions in each revolving door case. Rules and their implementation remain weak. With this article we point at the big picture missed by the Commission : the systemic revolving door in operation between FISMA and the financial industry and the role it plays in contributing to the capture of EU financial regulation by big financial corporations.33

The Commission doesn’t even seem to be trying to explain what the public interest in finance would be in its view, beyond the flawed assumption that what is good for the sector’s companies, is good for society as a whole, which it seems to adopt in practice.34

Conclusion

Our research shows that two out of the three commissioners, four out of the five directors, and one out of the three heads of units who worked in the financial regulation departments of the European Commission between 2008 and 2017 and who have now quit the Commission went on to work for the financial industry. It also showed one fifth (6/27) of all heads of units and one third of all deputy heads of units (7/22), have worked in the past for the financial industry.

This clearly creates a situation in which there is a high risk that a significant proportion of DG FISMA officials may not have the necessary distance and neutrality from the entities they are supposed to regulate that would allow them to serve the public interest. There is a risk that they will be unduly sympathetic to the financial sector’s vested interests.

As a public institution that plays such a key role in EU policy-making, the European Commission needs to protect itself from conflicts of interest, act to limit the revolving door, and adopt strict conflict of interest rules, cooling off periods, and post-career sanctions that break the social identification of its financial regulation department with the strongest firms it is supposed to be regulating.

----

Note: biographical data for this article has been collected from many different sources such as Commission organigrams and documents, conferences’ brochures, access to documents requests, the professional networking site LinkedIn, and press articles. It is therefore possible that some information might have escaped the authors who encourage whoever may want to share completions or updates to the information contained in this article to get in contact at vassalos [at] unistra [dot] fr

1 This one third refers to 19 of 61 top officials who served between 2008 and 2017: 12 Director-Generals, Deputy Director-Generals, and Directors on finance, 27 Heads of Units and 22 Deputy Heads of Units. We also looked at the three Commissioners responsible for financial regulation in this period and six anecdotal cases of DG FISMA policy officers. This makes a total of 70 individuals of which 31 have gone through the revolving doors and 29 have worked or are currently working in the representation of financial companies’ interests.

2 Yiorgos Vassalos is PhD candidate on political science in the University of Strasbourg and teaching assistant in the University of Lille. Parts of his research findings were first published in French sociology journal Savoir/Agir.

3 57% (83 of 145) non governmental members of DG FISMA’s expert groups represent corporate interests while only 6 out of 16 DG FISMA’s expert groups have no governmental members.

4 According to political scientists and economists a “principal-agent problem” appears when a person or entity is expected to act in the best interests of a third person or entity.

5 Close to half of Dutch regulators for instance feel it as a personal insult when someone criticizes the financial sector and “when [they] talk about the financial sector, [they] usually say ‘we’ rather than ‘they’”, Dennis Veltrop and Jakob de Haan, I Just Cannot Get You out of My Head: Regulatory Capture of Financial Sector Supervisors, DNB Working Paper, January 2014.

6 Elsa Wirsching, ‘The Revolving Door for Political Elites: An Empirical Analysis of the Linkages between Government Officials’ Professional Background and Financial Regulation’, 2018

7 Directorates F, G and H under DG MARKT and C, D and E under DG FISMA.

8 European Voice wrote: “The task force will also include Jörgen Holmquist, a former director-general for the internal market, and David Wright, Holmquist’s deputy. The two had to leave the department when Jonathan Faull was installed as director-general at the insistence of Gordon Brown, who was then UK prime minister.” https://www.politico.eu/article/commission-sets-up-taskforce-to-oversee-greek-reforms/

9 Angelo Riva and Paul Lagneau-Ymonet, Histoire de La Bourse (Paris: La Découverte, 2012), p. 107.

10 In contrast with the other directors’ cases here, Wright’s move could not be banned even by the three year cooling off period proposed by Corporate Europe Observatory. But his case completes a general picture of almost all of the top post-crisis officials of the Commission’s financial regulation Directorate ending up in the financial industry.

11 Without counting Directorate A dealing with human resources and communication.

12 LinkedIn profile viewed 8/2/2018.

13 Not every head of unit can become a director.

14 5 directors, 9 head of units, 7 deputy head of units, 6 policy officers, 2 Commissioners and 1 cabinet member.

15 LinkedIn profile viewed 8/2/2018.

17 LinkedIn profile viewed 8/2/2018.

18 This law firm specialises in the financial sector, declaring itself to be “one of the small handful of firms that leading companies and financial institutions around the world turn to for counsel” https://www.davispolk.com/firm/

19 LinkedIn profile viewed 8/2/2018.

20 Short bio in a publication Levin authored for the Center for European Policy Studies in p4 http://aei.pitt.edu/9561/2/9561.pdf

21 LinkedIn profile viewed 8/2/2018.

22 Hill & Knowlton is one of the ten biggest lobby consultancies in Brussels. It works for financial clients such as AIG, Trafigura, and Caronte Capital Investments.

23 LinkedIn profile viewed 8/2/2018.

25 Counting all policy officers, desk officers, team leaders, coordinators and policy analysts who contribute in drafting legislative and regulatory texts.

26 LinkedIn profile viewed 8/2/2018.

27 LinkedIn profile viewed 8/2/2018.

28 LinkedIn profile viewed 8/2/2018.

29 LinkedIn profile viewed 8/2/2018.

30 The Market in Financial Instruments Directives and Regulations 1 and 2 (2004, 2007 and 2014) set the basic legislative framework for the functioning of financial markets in Europe.

31 Charlie McCreevy, ‘The Credit Crisis – Looking Ahead’ (presented at the Institute of International & European Affairs, Dublin, 2009). http://europa.eu/rapid/press-release_SPEECH-09-41_en.htm?locale=en

32 ALTER-EU, ‘A Captive Commission: the Role of the Financial Industry in Shaping EU Regulation’, October 2009.

33 Academics such as Ewald Engelen (2011), Stefano Pagliari (2012), Cornelia Woll (2013), Mathilde Poulain (2016), practitioners like Thierry Philipponat (2014), and NGOs such as Corporate Europe Observatory have produced extensive evidence of this capture.

34 Finance Watch, ‘Representation of the public interest in banking’, December 2016, p. 30-33 http://www.finance-watch.org/press/press-releases/1311-pr-report-public-interest-banking

Comments

A very thorough examination of the conflict of interest that still occurs in the top decision making position in the most libertarian regionalization project. Thank you for all the great work