Too Big to Control?

The politics of mega-mergers and why the EU is not stopping them

Authors: Angela Wigger (Radboud University, The Netherlands) and Hubert Buch-Hansen (Copenhagen Business School, Denmark)

Download pdf version of this article

Executive summary

Some of the world’s most powerful global agro-chemical companies are gearing up to join forces, which will grant them even greater control over essential food markets. Although the European Commission is tasked with the role of ‘competition watchdog’, its track record for the enforcement of merger rules to date confirms a strong pro-concentration stance.

There is no other EU policy area in which such wide-ranging executive, judicial and legislative competences have been fused into an unelected entity: the European Commission. The result is that democratically-elected decision makers have no formal role in the overall course of the enforcement of EU competition rules.

Paradoxically, whereas cartels that reduce competition in specifically agreed areas are fiercely prosecuted, mergers and acquisitions that permanently eliminate all competition are stimulated. The Commission has legitimized its pro-concentration stance by referring to synergy effects, such as lower costs and thus lower prices for consumers, product innovation and the displacement of inefficient management structures. However, large transnational corporations have been the main beneficiaries to date, and smaller and less competitive companies have suffered. The Commission’s policy of consolidation of economic power into ever-fewer transnational corporations is thus neither in the interest of consumers nor society at large.

Introduction

The recently proposed mega-mergers between the agro-chemical giants Bayer and Monsanto (yet to be officially submitted), Dow and DuPont, and ChemChina and Syngenta will lead to unseen economic concentration in the markets for seeds and pesticides and other chemical inputs. These mergers will not only affect the future of biodiversity, wildlife and the conditions under which farmers produce their crops, but also the lives and food choices of billions of people around the world. Before these mega-mergers can take place, the fusing companies will need to get the permission of several competition authorities. At European Union (EU) level, the European Commission is the supranational competition authority in charge of allowing or prohibiting such mergers.

The EU has had supranational merger control rules on its books since 1990. Not only does the Commission have the power to permit or prohibit mergers above a certain turnover threshold, but it can also demand amendments to proposed deals. Judging from the Commission’s merger control practices over the past three decades, it is not surprising that it has already approved the mergers between ChemChina and Syngenta, and between Dow and DuPont, on the condition that parts of the companies will be sold off. Since 1990, the Commission has approved nine out of ten notified mergers without imposing any conditions, and has taken a strong pro-merger and thus pro-economic concentration stance. As former Competition Commissioner Neelie Kroes put it: “The merger tsunami is a good sign. It shows that the market itself is adapting to change, and that European companies are adapting to global competition. Healthy restructuring is taking place in many sectors… These processes… must be allowed to run their course without undue political interference.”1

On the website of the European Commission we read that EU competition policy “is about applying rules to make sure businesses and companies compete fairly with each other. This encourages enterprise and efficiency, creates a wider choice for consumers and helps reduce prices and improve quality.” But is EU competition policy really about fair competition and benefiting consumers?

In what follows we take a critical look at EU competition policy and its wider consequences for the organization of the economy. We first outline the key regulatory elements and the absence of democratic accountability in the field of competition policy. We then trace trends in the enforcement of competition rules, revealing a disturbing paradox: on the one hand, the Commission has aggressively prosecuted cartels and flexed its muscles against mammoth corporations such as Microsoft, Intel and Google. On the other hand, very few mergers have been blocked since the adoption of merger rules in 1990.

The EU ‘merger control’ system has thus facilitated large-scale (cross-border) mergers, and has made massive economic concentration possible. This is a major reason why EU competition policy is strongly supported by transnational business groups such as the European Roundtable of Industrialists (ERT), BusinessEurope and the American Chamber of Commerce to the EU (AmChamEU) – the actual beneficiaries of EU competition policy.

1. EU competition policy: a bastion of unchecked Commission power

The Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union includes provisions on anti-competitive agreements (Article 101), the abuse of dominant positions (Article 102), public undertakings (Article 106) and state aid (Article 107). These competition rules have been in place ever since the European Economic Community came into being with the Treaty of Rome in 1957.2 By targeting all sorts of private and public market barriers, competition rules were fundamental in the reconfiguration of several nationally fragmented markets into one giant common market. In the words of the Treaty, the rules were to ensure “that competition in the internal market is not distorted”. However, the Treaty did not refer to ‘mergers’ by name, even though mergers can undermine competition by leading to economic concentration. Only in 1989 did supranational merger control become a part of EU competition policy.

Since the early 1960s, the enforcement of the Treaty’s competition rules has been the prerogative of the Commission’s Directorate General for Competition, and in the case of disputes, the European Court of Justice. The Commission enjoys far-reaching competences with respect to the prosecution of anti-competitive agreements and the abuse of dominant positions. As Europe’s leading ‘competition watchdog’, it is empowered to impose significant economic sanctions on companies that abuse their dominant market position or that enter anti-competitive agreements (such as cartels). In addition to prosecuting corporate conduct, the Commission can prohibit state aid to companies, and thereby overrule the industrial policies of member states. Moreover, since 1990, the Commission has the power to block mergers whenever they are considered a significant impediment to effective competition in the EU.

The Commission acts as investigator, prosecutor, judge, jury and executioner, all in one. There is no comparable EU policy area where such wide-ranging executive, judicial, and legislative competences have been fused into an unelected entity. Neither the Council of the European Union nor the European Parliament can hold the Commission accountable in competition matters. The fusion between the three branches of the state – the legislature, executive and judiciary – within the Commission is supposed to ensure that competition rules are enforced by a politically independent competition authority, free from partisan influence. This means that democratically-elected decision makers cannot intervene in individual competition cases and thus have no formal say in the overall course of the enforcement.

The European Parliament and the Council are involved in the ordinary legislative process, and thus also in the formulation of legislation on how to deal with mergers and economic concentration. However, the Commission frequently circumvents official legislative processes in the field of competition policy by issuing quasi-legislation, for instance in the form of substantive notices, comfort letters, codes of conduct and guidelines. Such quasi-legislation does not need the approval of the Council or the European Parliament, and thus allows the Commission to bypass political contestation. Or as Competition Commission Vestager has declared: “There is simply no room to spare for political interference.”3

At the same time, the Commission puts a great deal of effort into presenting itself as a transparent and accountable regulatory body that listens to societal input through public consultations in the form of green and white papers. The Commission is not however obliged to justify why it disregards some voices and not others, nor does it choose to explain such decisions voluntarily. Thus, public consultations often merely create the illusion that a plurality of interest groups can exert influence on the future development of EU competition policy.

2. The enforcement paradox: promoting competition whilst facilitating economic concentration

Promoting competition

Two phases in the enforcement of EU competition rules can be distinguished throughout the history of European integration. In the first phase, lasting from the early 1960s until the early 1980s, the Commission’s enforcement practices were overall very lenient and a number of regulatory provisions were left untouched.

During this first phase, the Commission turned a blind eye to state aid such as subsidized loans, tax concessions, guaranteed procurement and financial guarantees, and export assistance was largely tolerated. It also did not intervene in the preferential treatment of state-owned companies, nor did it issue directives demanding the privatization of national monopolies, even though it could have done so on the basis of the Treaty of Rome.

The Commission moreover imposed mild sanctions on so-called cartels: agreements between competing companies that limited competition through fixing prices or sharing markets. When Europe was hit by the Great Stagflation Crisis in the 1970s, the Commission even permitted ‘crisis cartels’ in industries such as the steel, shipbuilding, chemicals, man-made fibres and textiles sectors, as well as in the sugar industry.4

More generally, the Commission took broader social and macroeconomic concerns – such as unemployment and industrial development – into consideration in the enforcement of competition rules, rather than focusing solely on competition. Competition policy, in other words, closely mirrored (protectionist) industrial policy.

In the second ‘neoliberal’ phase, stretching from the mid-1980s until today, the focus of EU competition policy gradually narrowed.5 Intense price competition was emphasized, and sophisticated econometric price modelling as a central reference point for determining anti-competitive conduct made its inroads into the Commission’s enforcement practices. The underlying rationale was, and still is, that intense price competition increases corporate efficiency, which allegedly benefits consumers through lower prices.

From the mid-1980s onwards, the Commission targeted different forms of direct and indirect state aid. By further specifying the conditions for state aid, the Commission narrowed the leeway for protectionist industrial policies at member state level. Moreover, the Commission endorsed the hitherto unused privatization directives under Article 106(3).

Privatization became a particularly high priority when the Commission took over the role of guiding the previously centrally planned Central and Eastern European countries through the transition to free market capitalism in the 1990s. Former state-owned enterprises ended up in a clearance sale, which created new opportunities for corporate expansion. Furthermore, the Commission prosecuted cartels with previously unseen rigour. Particularly from 2000 onwards, the magnitude of fines imposed on cartelists rose sharply (see Table 1). Cartels were newly considered to be the enemy of free competition. In the memorable words of Mario Monti, who served as Competition Commissioner from 1999 to 2004, cartels are “cancers on the open market economy”.6

The Commission has also recently imposed large fines on companies for having abused their dominant market positions. High profile cases concern the US giants Intel and Microsoft, which were fined respectively €1 and €2.2 billion, while Google seems to be the next high-tech company to face a hefty fine for abusing its dominant market position.

Table 1. EU cartel fines imposed on companies, 1990 – 2017

Years | Fines in Euros |

1990 - 1994 | 344,825,000 |

1995 - 1999 | 344,282,550 |

2000 – 2004 | 270,963,500 |

2005 – 2009 | 7,920,497,226 |

2010 – 2014 | 7,608,375,579 |

2015 - February 2017 | 5,091,156,000 |

Source: European Commission cartel statistics, http://ec.europa.eu/competition/cartels/statistics/statistics.pdf

To recapitulate: since the mid-1980s, the Commission has stepped up its efforts to promote competition in the common market by targeting cartels and abuses of dominant market positions, whilst prohibiting state aid and pushing for privatization. As will be shown in the next section, the Commission’s fierce pro-competition stance (on state aid and cartels) contrasts sharply with its lax attitude towards economic concentration in the form of mergers.

Facilitating economic concentration

When the Treaty of Rome was being negotiated, a coalition of government and industry representatives – including the Council of the Federation of European Industries, established in 1951 and encompassing the main employers’ associations from France, Belgium, the Netherlands and Germany – blocked the inclusion of merger rules. At the time, European companies were facing harsh competition from much larger and technologically more advanced US companies.7 Member state governments sought to boost ‘national champions’ in strategically important industries on the basis of proactive industrial policies and state aid, and considered it of the utmost importance that European companies could grow in size, create synergy effects and reap the benefits of economies of scale and scope production through mergers and acquisitions. Political opposition to supranational merger rules that could potentially block economic concentration was therefore fierce.

In the absence of merger rules during the decades of post-war European integration, the Commission promoted rather than prohibited cross-border economic concentration, and sought to stimulate ‘Eurochampions’. This permissive attitude towards economic concentration did not change with the 1989 adoption of the merger regulation, entrusting the Commission with exclusive control of ‘Community-dimension’ mergers. Companies meeting a certain combined turnover threshold were required to notify their envisaged merger at EU level. The Commission could then either prohibit the merger, subject it to certain conditions or allow it without further ado. As parliaments and member state governments had no say in the enforcement of competition rules, the European Court of Justice was the only ‘checks and balances’ element in the system.

The EU merger rules were adopted in the context of the broader neoliberal regulatory restructuring that started in the mid-1980s with the Single European Act (SEA). The SEA aimed to complete the Single Market by 31 December 1992 by introducing a range of substantial and legislative procedural changes to the Treaty of Rome. As part of the reinvigorated pro-integration spirit alongside the SEA, the Commission proposed supranational merger control rules, thereby responding to the calls of industry representatives who were increasingly struggling with what has been termed a ‘multiple jurisdictional overlap’: the necessity to simultaneously notify planned mergers to several national competition authorities, each enforcing different merger rules, notification procedures and timetables, while requiring different information and review fees.

As several industries had sought to overcome the limited domestic growth opportunities by relocating or subcontracting their production to areas in the world where labour was cheap, docile and unregulated and corporate taxes and environmental standards were low, they sought to overcome different national regulations by overriding EU level solutions. When the Commission announced its plan for adopting merger rules in its 1985 White Paper Completing the Internal Market, it assured business organisations like the European Roundtable of Industrialists (ERT), UNICE (today BusinessEurope) and AmChamEU that it would not take the line “that bringing the big together is bad”.8 Consequently, business organisations became proponents of a pan-European merger rule, pushing for regulation that would support corporate restructuring and advocating a so-called ‘one-stop-shop’ system whereby potentially contradictory merger reviews by national competition authorities would be eliminated.9

Merger control enforcement

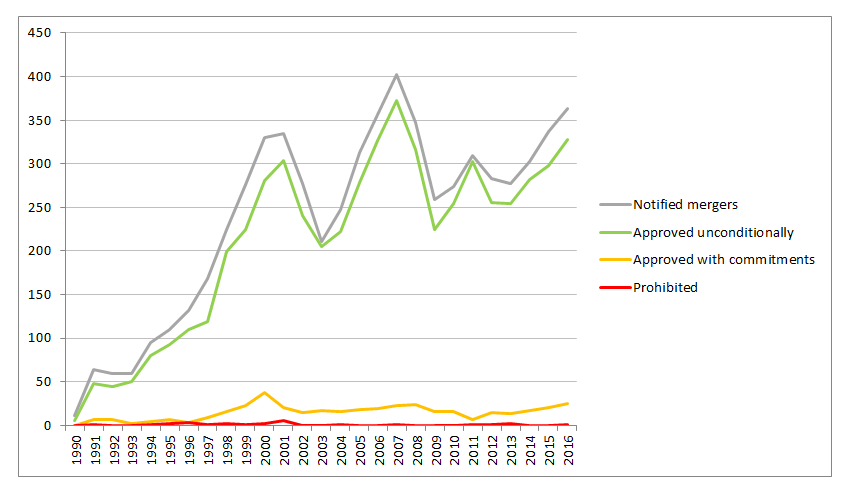

The track record for enforcement of the merger rules from 1990 until today confirms the Commission’s strong pro-concentration stance (see Figure 1). Only 25 of the 6,493 notified mergers – a mere 0.4 per cent – have been blocked (calculated up to 28 February 2017). Between 2002 and 2016, the Commission prohibited only seven mergers. While it is possible that a range of intended mergers have been withdrawn or were never notified anticipating a negative ruling,10 it is safe to conclude that this so-called ‘EU merger control’ has in fact greatly facilitated economic concentration.

Figure 1. Mergers notified to the European Commission, 1990-2017. Source: Calculated from European Commission merger statistics, up until 28 February 2017.

The Commission has legitimized its pro-concentration stance by referring to synergy effects, such as lower costs and thus lower prices for consumers, product innovation and the displacement of inefficient management structures.11 In 2007 alone, prior to the outbreak of the crisis, the Commission received 402 notifications, until that date the largest number of notified mergers in a year. The Commission interpreted this merger wave as a positive signal, indicating an economic upturn.12 Its permissive stance echoed US practices: as a competition official remarked, the EU and the US competition authorities had finally “agreed to let even monopolists compete”.13

Even after the economic crisis hit, the Commission continued to see mergers as an important part of a healthy economy with the argument that they would induce “much needed restructuring moves in certain industries” and that EU merger rules should “not stand in the way of the emergence of European companies capable of competing on the world stage”.14 The resulting power asymmetries between organized capital and labour, as well as other societal interests, have been of no substantial concern to the Commission.

In the neoliberal era, economic concentration has increased massively in Europe and beyond. Between 1980 and 1999, the total number of mergers grew worldwide at 42 per cent per year.15 In terms of aggregated value, global merger activity rose a hundredfold in this same period.16 Throughout the 1990s, mergers accounted for almost 90 per cent of FDI flows, indicating that so-called Greenfield investments – investments in new physical production and operational facilities from the ground up that create new jobs – were largely absent.17

Financial players and financial gains in the takeover market

Alongside the deregulation of financial markets and the growing importance of stock market capitalisation as a means for corporate finance, corporations were bought and sold as if they were random commodities. Hostile takeovers through the acquisition of a majority of shares without the mutual consent of executive directors became more frequent. Only a third of transactions were full mergers.18 The presence of a growing number of cash-rich lenders, hedge funds, private equity funds and other investors led to a situation in which mergers and acquisitions (M&As) were increasingly undertaken for the purpose of making short-term gains from speculative arbitrages rather than as productive investments. This was facilitated through the availability of a whole range of new financial products for lending, leasing, hedging and stripping facilitated leveraged buyouts, asset stripping, equity swaps and predatory bidding for shares. Mergers were further stimulated by the presence of activist financial players in M&As, known as ‘locusts’ or ‘asset-strippers’ in reference to their often voracious behaviour in breaking up company structures. As hostile takeovers generally provided the bidder with a free hand in the company reorganisation, hostile takeovers boosted share prices more than friendly ones.

At the turn of the new millennium, there were an estimated 31,019 mergers worldwide, with an aggregate volume of US$ 3.5 trillion (compared to US$ 0.5 trillion in the early 1990s).19 Traditionally, merger waves involved bigger corporations eating smaller ones. The 2000 merger wave however consisted of ‘mega-mergers’ involving large companies. After the peak in 2000 and the subsequent bursting of the ‘dot-com bubble’, the pace of merger activity slowed down slightly, but soon accelerated again to once more reach unprecedented heights.

In the run-up to the 2007-2008 financial crisis, new records were set for both the number and the size of corporate aggregate turnover. In 2006, eight of the ten largest global mergers in history were concluded, if measured in terms of the aggregated volume of the companies involved, while the sheer number of mergers also set new records.20 The involvement of hedge funds and private equity funds in merger transactions increased from 3 per cent in 2000 to 19 per cent in 2006.21

In the three years between 2008 and 2011, financial investment companies were responsible for up to 20 per cent of the 900 transactions that were notified to the Commission.22 Merger activity also involved financial players themselves, leading to the financial behemoths that – in the course of the crisis – eventually came to be considered ‘too-big-to-fail’. Even when the crisis hit in 2007, M&As in the financial sector continued.23

Unbridled corporate enmeshment

The global corporate restructuring processes of the past decades resulted in massive economic concentration, which can be seen from the fact that in many sectors only a small number of companies have high global market shares (see Table 2). Economic concentration through mergers are however only the tip of the iceberg. Commercial inter-company agreements in the form of strategic alliances, partnerships, joint ventures and business consortia have also proliferated. Although boundaries are often blurred, such forms of corporate enmeshment are much more common practice than mergers.24

Table 2. Industrial concentration among system-integrator corporations, 2006-09

Number of corporations | Global market share | |

Large commercial aircraft | 2 | 100 |

Automobiles | 10 | 77 |

Fixed-line telecoms infrastructure | 5 | 83 |

Mobile telecoms infrastructure | 3 | 77 |

Pharmaceuticals | 10 | 69 |

Construction equipment | 4 | 44 |

Agricultural equipment | 3 | 69 |

Cigarettes | 4 | 75 |

Source: adapted from Nolan and Zhang 2010

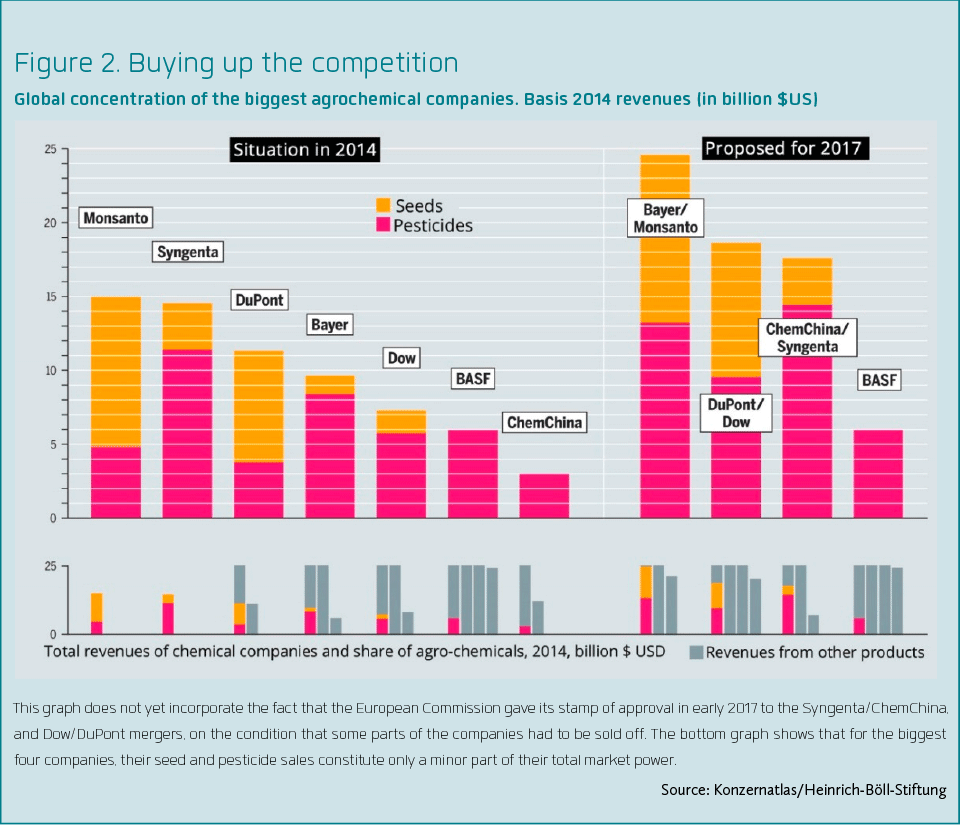

The same dynamic of corporate concentration can be observed in the European seed market. For example, according to a study commissioned by the Greens/EFA Group in the European Parliament 45 per cent of the UK’s wheat market has been captured by a single company, while five companies control 95 per cent of the EU vegetable seed market. The vitally important EU maize seed sector is dominated by five companies with collective market shares amounting to over half of the total of 4975 maize varieties registered in the European Common Catalogue. To further break it down: the maize varieties of DuPont Pioneer encompass 12.2 per cent, Syngenta 11.5 per cent, Limagrain 9.7 per cent, Monsanto 8.95 per cent, and KWS 8.9 per cent of the total market share.25

The graph below gives an overview of the global concentration in the seeds and pesticide sectors.

This vast global economic concentration has been made possible by the merger-friendly approach of the European Commission, as well as other competition authorities. There is a paradox at the heart of contemporary competition rule enforcement: whereas cartels are fiercely prosecuted, mergers and acquisitions are considered unproblematic and even desirable. As correctly pointed out by one scholar, a cartel between two companies temporarily reduces competition between them in specifically agreed areas, whereas a merger between two companies permanently eliminates all competition between them.26

This does not however imply that there is no competition as a result of economic concentration. Oligopolistic markets can be characterized by fierce price competition. At the same time, economic concentration can also lead to tacit collusion whereby companies abstain from competing with one another without explicitly forming a cartel agreement.

3. EU competition policy: in whose interest?

Transnational corporations seeking to further strengthen their global market positions and gain market access through mergers have been the main beneficiaries of the economic concentration facilitated by the Commission. It is thus not surprising that transnational and thus large businesses overall strongly support EU competition policy and that less competitive and smaller companies have been losing out. Attempts to form a counterweight through inter-company agreements come with the risk of cartel prosecution, and state subsidies are by and large considered as competition distorting and thus prohibited in the current climate of competition rule enforcement. EU competition rules function as a fictitious equaliser: they standardize corporations irrespective of their size and economic power into something they are not, namely equal market players.

The Commission’s enforcement practices have occasionally led to political contestation, most notably from the social forces that are on the losing side. These include organised labour and governments concerned about the economic survival of less competitive domestic companies and industries. For instance, the European Trade Union Confederation (ETUC), the umbrella organization of national trade unions representing the interests of workers at the institutional level of the EU, demanded that mergers should also be assessed with regard to their effects on employment levels, while ensuring that employees’ views are also heard. These demands have however consistently been ignored by the Commission.

The European Project has been and continues to be heavily influenced by corporate interests. The influence of business however must be differentiated, as not all businesses have corresponding interests. Moreover, the Commission is not a neutral transmission belt that is equally accessible to all groups in society.

At the same time, the Commission has not simply been ‘captured’ by the interests of big business. After all, the Commission enforces EU competition rules relatively autonomously, removed not only from parliaments and governments, but also from interest groups. The influence of business is not limited to ‘who gets to lobby whom, and how often’. Rather, business interests are much more intimately and structurally intertwined with the project of European integration.

The EU and its complex setup of institutions with the Commission at its core has an built-in structural bias that serves to advance (or obstruct) particular business interests.27 This ‘strategic selectivity’ means that the Commission, and also other EU institutions like the European Parliament and the European Courts, reflects the consolidation of much wider societal power asymmetries over time. With the rise of neoliberalism in Europe and elsewhere, the balance of power has shifted in favour of transnational business and particularly the financial sector, at the expense of smaller and nationally-oriented businesses and labour.

So, what about consumers? The Commission claims to act on behalf of consumers who will supposedly directly benefit from competition in the form of lower prices and better quality products. The effects of EU competition policy on consumers are however far from unambiguous. While intensified competition may indeed lead to lower prices, it should not be forgotten that consumers need employment before they can consume. Workers often pay the price of intensified competition as it exerts direct pressure on “the sphere of production, and particularly labour to deliver higher profitability, be it by higher productivity, longer working days or lower wages”.28 Competition in many cases has considerable downsides. The consolidation of economic power into ever-fewer transnational corporations is thus not in the interest of consumers or society at large.

- 1. Kroes, N. (2007), European Competition Policy in a Changing World and Globalised Economy. Speech 07/364, Brussels, 5 June.

- 2. For the sake of simplicity, we use the label EU competition policy also for the pre-EU period. All article numbers refer to the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union.

- 3. Vestager, M. (2015), The values of competition policy, 13.10.

- 4. European Commission (1977): Sixth Report on Competition Policy. Brussels and Luxembourg: Commission of the European Communities. Brussels: Archives of the European Commission

- 5. See Buch-Hansen, H. and A. Wigger (2011), The Politics of European Competition Regulation. A Critical Political Economy Perspective. New York: Routledge.

- 6. Monti, M. (2001), Why Should We Be Concerned with Cartels and Collusive Behaviour? In Fighting Cartels – Why and How?, edited by Konkurrensverket.

- 7. In 1960, 27 of the 30 largest industrial companies worldwide originated from the US. In Adams, W., and J.W. Brock (1990), Mergers and economic performance. The experience abroad. Review of Industrial Organization 5(2): 175–88. Page 175.

- 8. The Financial Times (1985), The Competition Commissioner Talks to Paul Cheesright, 27 March. Page 2.

- 9. European Round Table of Industrialists (1988), Merger Control: ERT Standpoint on the Proposed EC Regulation. Brussels, 1 June.

- 10. The very existence of the EU merger control system may have prevented some mergers. Companies expecting that the envisaged merger will be blocked will not notify to the Commission. Moreover, 177 notified mergers were withdrawn before the Commission reached a decision - in some cases because the Commission signalled that it would not allow the merger.

- 11. European Commission (2011), The Past and the Future of Merger Control in the EU. Global Competition Reviews Conference. Speech 10/486. Brussels, 28 September.

- 12. European Commission (2006), Developments in Competition Policy for the Second Half of 2006. Brussels, 25 October. Page 2.

- 13. Pate, H. (2004), US and EU Approaches to Antitrust Issues, accessed 24 October 2011.

- 14. European Commission (2006). Page 2.

- 15. UNCTAD (2000), World Investment Report: Cross-border Mergers and Acquisition and Development. New York: United Nations. Page 106.

- 16. Oram, J. (2003), Corporate Breakdown Standing up to the Competition? New Economics 5, January.

- 17. UNCTAD (2000). Page 10.

- 18. UNCTAD (2000). Pages 10, 113.

- 19. Bannerman, E. (2002), The Future of EU Competition Policy. London: Centre for European Reform. Page 3.

- 20. The Financial Times (2007), Cool Heads Will Bring in the Best Deals. Boardroom Discipline is Vital if the M&A Boom is to Benefit Shareholders. February 28. Page 6.

- 21. McQueen (2009), Private Equity: Visionaries or Locusts?, accessed on 24 October 2011. Page 8.

- 22. Anttilainen-Mochnacz, H., K. Fountoukakos, and L.G. Craig Pouncey (2012), Mergers. European Antitrust Review: 28–34.

- 23. To give but a few examples: JPMorgan acquired both Bear Stearns and Washington Mutual; Bank of America absorbed Merrill Lynch; Wells Fargo merged with Wachovia; BNP Paribas with with Fortis; Lloyds TSB with HBOS; Nomura and Barclays Capital divided Lehman Brothers; Santander purchased ABN Amro’s Latin American branches and Abbey National and Bradford & Bingley; while Commerzbank acquired Dresdner Bank. In Nolan, P. and Zhang, J. (2010), Global Competition After the Financial Crisis. New Left Review 64 (July/August): 97-108. Page 101.

- 24. Goddard, C.R. (2003), Defining the Transnational Cooperation in the Era of Globalization. In International Political Economy. State Market Relations in a Changing Global Order, ed. C.R. Goddard, P. Cronin, and K.C. Dash. Basingstoke: Palgrave McMillan. Page 438.

- 25. Mammana, I. (2014), Concentration of Market Power in the EU Seed Market, Study commissioned by the Greens/EFA Group in the European Parliament.

- 26. Schröter, H.G. (2013), Cartels Revisited. An Overview on Fresh Questions, New Methods, and Surprising Results. Revue économique 64(6): 989–1010.

- 27. Jessop, B. (2008), State Power. A Strategic-Relational Approach. Cambridge: Polity Press.

- 28. Bryan, D. and Rafferty, M. (2006), Capitalism with Derivatives. New York: Palgrave. Page 162.

Comments

Capitalism can contain but is distinct from a free market. We're protected from cartels, but almost never mergers. Capitalists don't get in the way of capital, but mergers do get in the way of a free market.

speaking about "The Commission claims to act on behalf of consumers who will supposedly directly benefit from competition in the form of lower prices and better quality products. " you should definitely mention the fact that as soon the big one has eliminated the smaller ones through cheaper prices - sometimes under production costs to eliminate competition - THEN they rise the price... yes they do. But sometimes this tactic also breaks their neck. But the CEO and banks etc allways get their share...