Barroso’s Gold-plated revolving door

Never before has a former European Commission official been criticised as much for their post-EU career as ex-Commission president Barroso since he joined infamous US investment bank Goldman Sachs earlier this summer. Despite its scandalous nature, his move did not come as a complete surprise, given previous revolving door cases involving former EU commissioners.

Citizens have every reason to ask if Barroso’s move goes against the public interest: evidence already points towards a gross violation of the EU Treaty. It would only be fair if Barroso was forced to choose between his new position with the banking giant and his generous EU pension.

José Manuel Barroso’s decision to become chairman of Goldman Sachs International and an adviser to the big investment bank very much fits with his stewardship of the Commission. From the beginning, his leadership followed a corporate agenda on a very wide range of issues, with its close links to the biggest businesses and banks in the EU representing a key trait of the way the European Commission operates.

Barroso’s latest spin through the revolving door breaks no rules of the Commission, because the rules for ex-commissioners are weak and only last for 18 months after leaving office. But the question is if those rules ensure the Commission lives up to EU Treaty article 245 which states that former commissioners will respect “their duty to behave with integrity and discretion as regards the acceptance, after they have ceased to hold office, of certain appointments or benefits”. We believe the Barroso case shows that they don't. His spin through the revolving door from the helm of the Commission to the helm of Goldman Sachs is a risky business for citizens in the EU.

Invoking article 245 against Barroso

The wording in article 245 about how commissioners should act after leaving office aims at preventing these high-level politicians’ subsequent careers from damaging the reputation of the EU institutions, notably the Commission, and that they do not undermine the Commission’s work.

The article has been invoked once before, by the Council, when a former commissioner for industry, Martin Bangemann, announced he would take a job with Spanish telecommunications company Telefónica. The Council responded by opening a case against him at the European Court of Justice, arguing he was in breach of article 245 (then article 213), but in the end, it backed down.

Today, there are calls to launch a similar case against Barroso including, in recent days, by ALTER-EU and WeMove.EU. In the European Parliament, dozens of MEPs from left to right have expressed their concern. One such open letter to President Juncker calls for action against Barroso based on article 245, and argues that “Barroso's move to Goldman Sachs, after presiding over the Commission for two terms, during which important banking regulation was enacted by EU institutions, damages the reputation of the Commission and threatens the credibility of the EU as a whole among EU citizens”.

And the Barroso case appears to contain even more risks than the Bangemann case. Goldman Sachs has on many occasions defined political aims in the field of financial regulation that are highly controversial. It is known to use dubious methods, both in the market place and when pursuing its political agenda; and it is powerful, operating a well-oiled lobby machine that helps it meet its ends. With that in mind, Barroso's move to Goldman Sachs has the potential both to ignite scandals and to put the EU institutions in an awkward position.

Barroso vs. the EU at Brexit negotiations

At the time of his appointment, Barroso told the Financial Times that as part of his role at Goldman Sachs he will do what he can to “mitigate the negative effects” of the Brexit decision. Barroso will be a key part of Goldman Sachs’ artillery as it does battle to retain access to EU financial markets, via so-called equivalence or passporting rules. Whether it is at the UK or EU level, Barroso will likely be able to deliver insights, access and influence, hardly in keeping with the duty to behave with integrity and discretion.

“Of course I know well the EU, I also know relatively well the UK environment … If my advice can be helpful in this circumstance I’m ready to contribute, of course,” said Barroso.

And it seems very likely that both Goldman Sachs and hence Barroso, will play an important role in the Brexit process. Goldman Sachs is well connected to key players in the UK government, as explained in a report by SpinWatch. And London was always the perfect base from which the bank could not only be involved in EU financial markets, but influence the rules of the game as well. It is no surprise that the UK government and six investment banks, including Goldman Sachs, have signed a joint statement to work together to defend the interests of the financial centre in the UK, the City of London, in the post-Brexit referendum world.

It is hard to imagine a more toxic scenario in a revolving door case if a former Commission President ends up supporting the 'other side' in EU exit negotiations, negotiations which are bound to bring serious matters into play. In the aftermath of the financial crisis, the UK government was always very hesitant to support financial regulation – it was often a vociferous opponent of stronger regulation - and the outcome of the Brexit negotiations will go a long way in determining the fate of both existing and future financial regulation in the EU and UK.

Barroso to work for Goldman Sachs’ financial deregulation agenda

Both Goldman Sachs and the current UK government depict the interests of the financial sector as pretty much the same as those of humanity. Goldman Sachs’ chief executive Lloyd Blankfein has even boldly stated that his bank is “doing God's work”. But after the crisis of 2008, very few would accept such a claim. The public interest is, in many ways, the polar opposite of the interests of the financial corporations.

Goldman Sachs has been a consistent lobbyist against financial regulation on both sides of the Atlantic. The lightly-veiled threat “Operations can be moved globally and capital can be accessed globally”, as voiced by Blankfein in 2010, sent a clear message: ‘If you pressure us too much, we'll take our operations – and our money – elsewhere’.

In practically all important lobby battles since the financial crisis, Goldman Sachs has worked with European allies, and friends in the financial sector, to stop ambitious proposals to rein in the power of the financial sector. As just a few examples:

When the EU started looking at rules (via the review of the so-called Markets in Financial Instruments Directive and rules for credit default swaps) for some of the toxic financial instruments that had caused the financial crisis, Goldman Sachs claimed “the case has not yet been made for additional regulation”. It even warned Commission officials against “possible over regulation”.

When the Commission started considering stronger rules for banks to ensure financial stability, Goldman Sachs lobbied against practically every new step suggested.

While the investment bank acknowledged in 2009 that a massive inflow of speculative money into commodities, including food, “has boosted prices” sparking hunger in many parts of the world in 2008, Goldman Sachs still went on to fight new rules in the European Union (position limits), that were supposed to deal with the problem.

Goldman Sachs was also active in the industry-led campaign against the introduction of a Financial Transactions Tax. In an attempt to alarm the financial sector about the proclaimed horrific tax burden ahead of the introduction of the tax, Goldman Sachs said it would amount to €170 billion, according to an article in its research newsletter titled "Financial Transaction Tax: how severe?". This was a figure far higher than the Commission's estimate of €34 billion annually.

Besides working to keep regulation at bay, the investment bank has an offensive agenda as well. Recently, Goldman Sachs has mounted a strong defence of the Commission’s proposal for a Capital Markets Union which will remove obstacles to the free movement of capital, and will strengthen the markets in securities (tradeable financial assets). The Financial Times called it “A dose of deregulation”. At least six of Goldman Sachs’ 23 meetings with the elite of the Commission since December 2014 have been on the topic of the Capital Markets Union.

With all this in mind, the question is: what will Barroso do for Goldman Sachs? On so many occasions, the investment bank has fought single-mindedly to stave off attempts to rein in the financial sector, and has often fought proposals from the Commission. What input will Barroso give to his colleagues at the bank? What, for instance, will be his contribution when the Financial Transactions Tax reappears on the agenda of the Council and the Commission? It seems highly unlikely that he will be able to please both his old colleagues and his new employers.

Whatever advice he gives on this and other issues, it is likely to have an impact, as Goldman Sachs has a well-oiled lobby machine.

Barroso could boost the effectiveness of Goldman Sachs’ lobbying

Goldman Sachs is a major lobby actor at the EU level. In 2015 it declared €1,000,000 - €1,249,999 lobby spend and two staffers with European Parliament lobby passes. But this wasn’t always the case. For years, Goldman Sachs was lobbying the EU institutions but it refused to join the EU lobby register. When it finally joined in November 2014 it only declared less than €50,000 annual lobby spend. NGOs challenged this totally implausible figure, via a complaint to the lobby register authorities, and since then, its declaration has crept up to €700,000 - €799,999 and then finally to today’s figure. Its EU lobby spend declaration should be compared with the US$3,680,000 lobby spend that it declared in 2015 in the US lobby register.

What is especially significant in Goldman Sachs’ lobby profile is its access to the Commission. According to data on the LobbyFacts.eu database, it has had 23 high level meetings with the Commission since December 2014, putting it 31st on the list of 777 companies that have held high-level lobby meetings with the Commission. That level of Commission access is impressive and it can boast of recent meetings with at least seven commissioners: Hill, Dombrovskis, Katainen, Oettinger, Moscovici, Cañete and Malmström. Due to the absence of Commission transparency rules prior to December 2014, we do not have a clear idea about Goldman Sachs’ Commission access prior to this time. However, previous CEO research has shown that the investment bank met with then Commissioner Ollie Rehn at least three times in 12 months, likely to discuss the Commission’s response to the eurocrisis.

Access to the Commission takes many forms and one that should be taken into account are expert groups. The Commission’s expert groups play a hugely important role in the EU legislative process, often providing policy inputs which form the basis of proposed new laws. The High Level Group on the Financial Crisis (also known as the De Larosière Group) was set up by the Council and the Commission to write recommendations for the EU's response to the financial crisis in 2008. Of the eight men in the group, four were closely linked to corporate giants, and included Goldman Sachs’ adviser Otmar Issing, delivering “a strategic coup” to Goldman Sachs. It was also a member of the derivatives expert group; the group aimed at achieving a “barrier-free Single European market for clearing and settlement of securities transactions”; and an observer to the group which monitored compliance of the industry’s self-regulation tool.

Also, it is not unusual for Goldman Sachs to snatch a place in advisory bodies of other EU institutions. These include the so-called market contact groups of the European Central Bank, where it has a seat on the Bond Market Contact Group and the Foreign Exchange Contact Group; as well as the standing committees of regulatory authorities including the European Securities and Markets Authority.

Also, to assess the strength of the Goldman Sachs’ lobbying machine, it is important to note that very often, Goldman Sachs is not present in name. The bank is a member of a plethora of lobby groups, and often has its people in key positions. It is a member of financial services trade associations including the Association for Financial Markets in Europe (AFME), which is in the top 10 biggest EU lobbies according to declared lobby spend; TheCityUK; the Futures Industry Association Europe (FIAE); the International Swaps and Derivatives Association (ISDA); and The Investment Association (IA) among others. When individual companies combine their financial weight and influence, the result can be greater than the sum of its parts.

One example of a joint lobby effort is ISDA. In 2010, Goldman Sachs and derivatives lobby group ISDA were given the dubious honour of being named the Worst EU Lobbyists of 2010, nominated for their aggressive lobbying to defend their ‘financial weapons of mass destruction’, also known as derivatives. Derivatives played a key role in the 2008 financial crisis, the 2008 food crisis and the 2010 euro crisis and there were subbsequent calls for tighter regulation. But ISDA and its notable member Goldman Sachs lobbied hard to make sure the final regulation was kept as lax as possible.

When the Goldman Sachs’ lobbying machine gets moving, how can Barroso – who has loads of insider know-how on EU decision making – help his employers? And will anyone on the outside ever get to find out? What doors can he open for Goldman Sachs, and will it be consistent with “integrity and discretion”?

Barroso in a corporation with flawed ethics?

Imagine if a former Commission President were enmeshed in a scandal, be it if his new employer was accused of using illegitimate business practices that hurt the EU economy, or if it was accused of breaking or undermining EU rules, or accused of using bribery. Such scenarios would undeniably harm the “integrity” of the EU institutions, and as recent history shows, by joining Goldman Sachs, Barroso is sailing very close to the wind.

The most famous example of a Goldman Sachs’ blow to the EU economy is from the financial crisis of 2008.

“Goldman’s conduct in exploiting the residential mortgage-backed securities market contributed to an international financial crisis that people across the country ... continue to struggle to recover from.”

Not our words but the words of United States Attorney for the Eastern District of California, in relation to the Department of Justice’s announcement that it would fine Goldman Sachs US$5.06 billion for the bank’s conduct in the “packaging, securitization, marketing, sale and issuance of residential mortgage-backed securities” between 2005 and 2007.

“Today’s settlement is another example of the department’s resolve to hold accountable those whose illegal conduct resulted in the financial crisis of 2008” [emphasis added], said Principal Deputy Assistant Attorney General Benjamin C. Mizer, head of the Justice Department’s Civil Division.

Other big banks have had to pay for previous "fraudulent practices" too.

The illegal conduct mentioned in this damning verdict is about the bank's responsibility (with others) for misconduct that helped spark the financial crisis, but elements in Goldman Sachs' conduct ahead of the crisis were particularly relevant from a European perspective. In 2007, Goldman Sachs established a project called Abacus 2007AC1. The concept was two-pronged. On the one hand, Goldman Sachs allowed a hedge fund to pick so-called collateralised debt obligations to be sold to customers like insurance company ACA which put US$951 million on the table. Among other prominent customers were European financial corporations like the German bank IKB Deustche Industriebank AG and Dutch bank ABN Amro. At the same time, Goldman Sachs helped the same hedge fund to bet against the very same investments it had picked out. Since the hedge fund in question, managed by Henry Paulson, was and is quite big, a major bet was possible. And as it turned out, it was quite profitable. It made US$3.7 billion and the fund jumped in value by 590 per cent. The consequences for the clients on the other side of the deal were highly problematic. Losers included IKB Deutsche Industriebank (US$150 million) and ABN Amro (US$840 million). Later the same year, IKB nearly collapsed, but was saved by an injection of €10 billion from the German government. At that time, the German state owned 40 per cent of IKB; by 2008, it owned 90 per cent when IKB was sold to US private equity fund Lone Star.

On another note, Goldman Sachs has sparked just as much controversy by helping the Greek government to bypass rules on official debt. In 2001-02, at the time of the launch of the euro, the Greek government was looking to reduce its overall debt burden in order to meet strict public finance rules for eurozone membership. In a deal concocted by Goldman Sachs, and for which it apparently reaped hundreds of millions of euros, Greece’s finance books were ‘cooked’. A two billion plus loan to Greece, arranged by the bank, was disguised as a “cross-currency swap” of dollars and yen for euros using fictitious exchange rates. Staff at the Greek debt management agency at the time have since argued that the “department did not understand what it was buying and lacked the expertise to judge the risks or costs”. The deal was not technically illegal at the time, but Eurostat banned them in 2008. For Greece, the short-term result of the 2001-02 deal was a two per cent reduction in its on-the-books public debt; the longer-term result was that by 2005, the country owed almost double what it had put into the deal in the first place. At the time, Mario Draghi, now head of the European Central Bank, was managing director of the international division of Goldman Sachs.

And now Goldman Sachs is involved in a bribery scandal.* A court in London is currently gripped by the salacious details emerging from the legal case between the Libyan Investment Authority (LIA) which is suing Goldman Sachs for US$1.2 billion of losses on trades conducted in 2008. The court has heard allegations that a Goldman Sachs senior banker at the time gave iPods to staff at the LIA and even paid for prostitutes and private jets. The LIA was a project of the then Libyan dictator, Muammar Gaddafi, to manage the country’s oil wealth and in Goldman Sachs’ own words was “a very significant account for the firm”. The LIA apparently lost almost all its investment through the trades, while Goldman Sachs reaped “eyewatering” profits. Goldman disputes the case and argues that the LIA was a victim of the 2008 financial crash and not any wrongdoing on its part.

When taken together, these three examples risk depicting a financial corporation with apparently flawed ethics. If a former commissioner is associated with such a company, can he really argue that he has made a career choice based on “integrity and discretion”?

Goldman Sachs: repeatedly gaining influence via the revolving door

Goldman Sachs’ access, influence and know-how in the EU institutions including the European Commission and European Central Bank (ECB) has surely been boosted several times by its penchant for recruiting through the revolving door. The Barroso appointment is only the most recent of a long line of personnel moving seamlessly from the bank to public institutions, or vice versa. In fact, Barroso replaces Peter Sutherland as chairman of Goldman Sachs International; Sutherland was previously the director-general of the World Trade Organisation and a European commissioner.

Mario Monti was a European commissioner from 1995 to 2004, with responsibility for the internal market and then competition matters. Subsequently, Monti was asked by then Commission President Barroso to draft a report on the future of the European single market. At the same time, he was serving on the board of international advisers to Goldman Sachs. He was then catapulted into power as unelected prime minister of Italy in November 2011, after the ECB effectively toppled the Berlusconi government, in order to implement austerity and reforms as demanded by the EU institutions.

Mario Draghi, now head of the European Central Bank, was previously managing director of the international division of Goldman Sachs from 2002-05 and in charge of the department which, shortly before his arrival, helped Greece to disguise the true extent of its debt (see above). Meanwhile, Draghi maintains his membership (as his predecessor ECB presidents have done) of the Group of Thirty, a murky grouping which brings together central bank leaders with those from the major private banks, including several individuals with prior links to Goldman Sachs, such as current Bank of England governor Mark Carney who spent 13 years in its London, Tokyo, New York and Toronto offices.

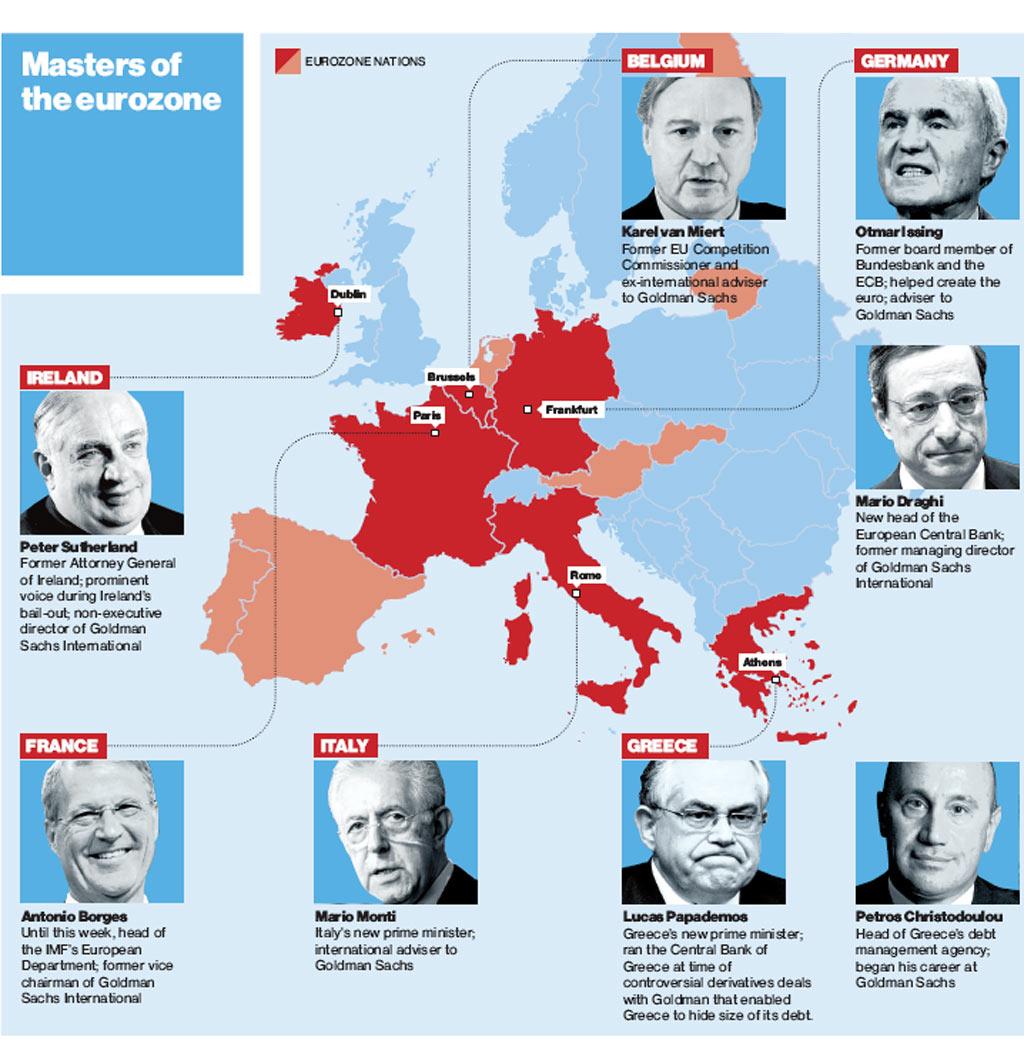

In 2011, The Independent published this infographic to demonstrate the revolving door links between Goldman Sachs and key figures in the eurozone, such as Petros Christodoulou, who worked for Goldman Sachs, as well as for the Greek National Bank and who had a leading role in the Greek team negotiating with the Troika.

The current commissioner responsible for EU research and innovation Carlos Moedas previously served in the Portuguese government as the secretary of state to the prime minister, responsible for overseeing the implementation of the Troika's structural reform programme. Earlier in his career, he worked for - you guessed it - Goldman Sachs' mergers and acquisitions division.

This symbiosis between high finance and public office is also really visible in the US where there is such a big “interchange of personnel that it can be hard to tell where Goldman Sachs ends and the White House begins”. People who know the system and how to work it are priceless when it comes to influencing policy, whether it is in the US or in the EU.

Conclusion

The question is if the EU institutions will stand for this or if, finally, with Barroso, they will be forced to put their foot down.

We do not think that Barroso’s ongoing duty to act with “integrity and discretion” as required by Treaty article 245, is compatible with his new roles of chairman and adviser at Goldman Sachs International. Goldman Sachs has been associated with too many scandals, has been too closely associated with the origins of the financial crisis, and is too active as an EU lobbyist, for it to be appropriate for Barroso to take on such roles. He should immediately re-consider, especially in the light of the groundswell of political and public criticism which greeted the announcement.

The EU treaty also says:

“In the event of any breach of these obligations [article 245], the Court of Justice may, on application by the Council acting by a simple majority or the Commission, rule that the [commissioner] concerned be, according to the circumstances, either compulsorily retired in accordance with Article 247 or deprived of his right to a pension or other benefits in its stead” [emphasis added].

We think it is imperative that the Commission and Council take action to refer Barroso to the Court of Justice and that he loses his entitlement to a Commission pension, a pension which could amount to more than €130,000 a year for life, once Barroso reaches the age of 65. Furthermore, the Commission should overhaul the current revolving doors rules to prevent such moves by other ex-commissioners in the future. There should be an extended cooling-off period for ex-commissioners from 18 months to three years, with the rules for Commission presidents like Barroso extended to five years.

Just last week, ALTER-EU and WeMove.EU launched a petition to Commission President Juncker demanding penalties for Barroso and tougher rules to prevent such a thing happening in the future.

For the Commission, this scandal is not going away in a hurry.

* Update on 18 October 2016: On 13 October 2016, the Libyan Investment Authority (LIA) lost its case against Goldman Sachs in the London high court. The presiding judge said: “I find that there was no protected relationship of trust and confidence between the LIA and Goldman Sachs. Their relationship did not go beyond the normal cordial and mutually beneficial relationship that grows up between a bank and a client. Goldman Sachs did not become a trusted adviser or a ‘man of affairs’ for the LIA.”