Recruitment Errors

The European Food Safety Authority (EFSA) will probably fail, again, to become independent from the food industry

Its motto is “trusted science for safe food”.

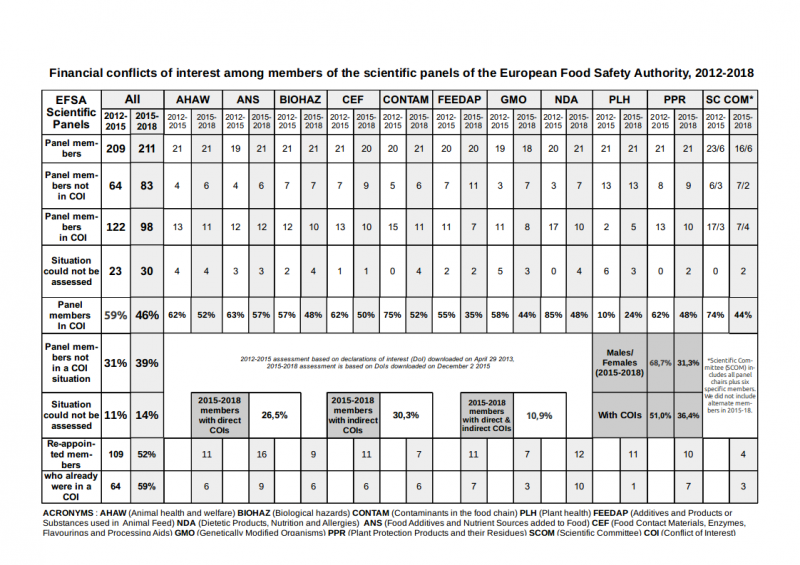

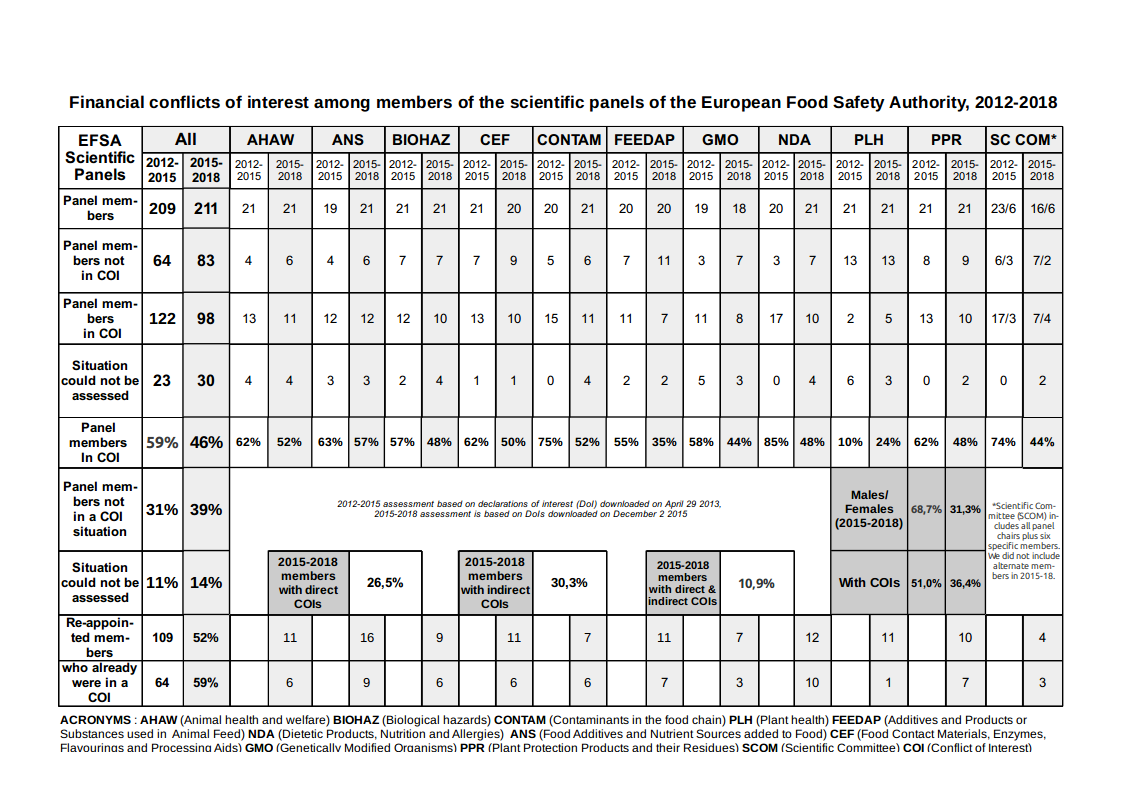

But year after year the European Food Safety Authority (EFSA) has been hit by conflicts of interest scandals. Conflict of interests still abound in EFSA’s panels, with nearly half (46%) of current experts on EFSA panels in a financial conflict of interests, according to our assessment.

For four years in a row, the European Parliament has demanded that EFSA becomes independent from the food industry. On 21 June 2017, the agency’s Management Board will vote new independence rules for the agency’s experts. Given the agency’s reluctance to change, we fear that the situation will not really improve. [UPDATED on June 20]

(download a pdf of the report)

EFSA's mission is to provide independent scientific advice to the European institutions on food safety matters. Assessing the risks related to industry products represents about two thirds of its workload.

In 2013 Corporate Europe Observatory performed a systematic assessment 1 of all EFSA panels, and found that almost 60 percent of EFSA’s experts had direct and/or indirect financial interests with companies whose products the Authority was assessing. These include products European citizens put in their shopping baskets and feed to their families every day.

Conflict of interest scandals have kept erupting regularly (on most issues but in particular food additives, pesticides, GMOs, nutrition recommendations…) ever since NGOs and the media discovered that EFSA’s independence policy was, essentially, dysfunctional.

Today, we publish an updated assessment of EFSA’s ten scientific panels (211 experts), whose outcome is, despite commitments by the agency to improve his recruitment, only slightly better: the proportion of experts with a financial conflict of interest has only gone down from 59% to 46%2.

While EFSA’s draft new independence policy is a very marginal improvement to the current one, it still reproduces its main problems and loopholes. To illustrate each of the main flaws in this policy, for each loophole we publish a sample of experts currently sitting on EFSA’s panels who have financial interests in regulated companies (or their lobby groups).

Unless the agency’s Board takes serious ownership of developing the new independence policy – which thus far has clearly been steered by EFSA’s management to keep business as usual at the agency – it is highly unlikely to be fit for purpose.

The reason for this situation is simple: EFSA has few resources and has always prioritised excellence over independence. However, this is a false dichotomy: for a public food safety regulator, excellence is impossible to reach without independence from the food industry.

Furthermore, it is entirely possible to preserve both EFSA’s integrity and access to the best expertise by inviting the broadest range of experts, including those from industry, to dedicated hearings, but leaving the deliberation and writing phases of EFSA’s scientific opinions to independent experts. It is difficult to understand why EFSA’s management has not opted for such a system, in place for instance at the International Agency for Research Against Cancer and whose robustness has been demonstrated in the recent glyphosate drama.

The European Parliament has demanded every year for the past four years that when EFSA appoints new experts, as a matter of principle, it respects a two-years cooling-off period for financial interests in all regulated companies (and organisations funded by them).

But EFSA’s management has been opposed to the idea from the very start. Today, all the signals we receive from this agency are that it simply will not do it. We hope EFSA’s Management Board will prove us wrong.

I. Financial conflicts of interest in EFSA’s scientific panels

In July 2015, EFSA renewed its panels (panels are appointed for three years). It described its new experts by announcing that “many of them come from universities and research institutes”. Did this mean that these new panels are, on average, more independent from companies EFSA exists to regulate?

Indeed, EFSA is not any scientific organisation but a public regulatory agency, whose assessment means life or death in the EU for regulated products in the agribusiness and food industries. Following the financial interests of its external experts points to many structures and tactics industry uses to make sure EFSA says the ‘right’ thing.

Our updated (but simpler) assessment shows not much has improved: the proportion of financial conflicts of interest has remained very high. 46% of panel members3 have at least one financial conflict of interest with a regulated company. Among the experts composing the 2015-2018 EFSA panels, 52% are re-appointments.

Strikingly, the proportion of experts with conflicts of interest in 2013 among these re-appointments is almost exactly the same as the general proportion of experts with conflicts of interest in 2012-2015 (59%). Difficult not to see this result as a sign that EFSA’s management did not take independence from the food industry at all into consideration when deciding whether or not to re-appoint these experts. Beyond PR and a few small measures, EFSA has clearly not taken significant action on the problems we had identified.

The methodology we used is comparable to that in 2013: to replicate EFSA’s working conditions, we only looked at the interests declared by the experts in their declarations of interest and CVs (EFSA does not check whether there are omissions)4. But we checked each individual interest declared by the 211 experts, a very significant undertaking.

Therefore, we considered that a direct financial transfer from regulated companies to an expert and/or his research team (consultancy contract, research funding, ownership of shares) in the past five years5 constituted a direct financial conflict of interests, and that positions in organisations6 obtaining more than 20% of their funding from regulated companies7 (or organisations controlled by them) in the past five years were indirect financial conflicts of interests8. The same threshold (20%) was also applied to public-private partnerships, with an additional case-by-case analysis.

Although they do matter as well, we left intellectual conflicts of interest out of the scope of our assessment, as we consider that unlike financial ones which should not be allowed on panels, intellectual conflicts of interest should be managed by collegiality (ensuring a diverse range of expertise and opinions on the panel)9 and transparency (to enable accountability).

It is important to underline that a financial conflict of interest is not an indication of a lack of integrity of, or a moral judgment passed on an expert but the sign that EFSA made a recruitment error. As a matter of fact, a financial conflict of interest places individuals in a situation where they are torn between two contradicting interests: defending public health and the environment, as per EFSA’s mission, and being financially dependent on regulated companies, whose interest is to obtain a ‘good’ scientific opinion from EFSA in order to take their product to market. The scientific literature is very clear on this point: financial conflicts of interest have a measurable impact on conclusions reached10.

Crash course on regulatory capture

Regulatory capture11 is a theory developed by George Stigler, Nobel laureate economist of the Chicago School of Economics, who developed it in a 1971 seminal article. “The state – the machinery and power of the state – is a potential resource or threat to every industry in the society”, he wrote. “A central thesis of this paper is that, as a rule, regulation is acquired by the industry and is designed and operated primarily for its benefit.”12

The reasoning behind this argument is that regulators need information retained exclusively by the sector's players themselves. This places them in an information dependence vis-à-vis the industries they regulate, which is a way for these to control regulators.

Hence, the challenge for regulators to escape this trap consists in maintaining and developing independent sources of expertise.

Regulatory agencies are typical targets for industry's influence tactics. But, although corruption and other forms of brutal interference in the decision-making process exist, industry's influence tactics in this domain are rather about building long-term, smooth personal and professional links that will lead the officials or the experts to develop excessive empathy for industry’s interests.

How to resist daily politeness, useful partnership proposals or appealing future career opportunities forever if there is no institutional control on these practices? The inconvenient truth is that regulators and experts are only human beings...

An instructive book called “The regulation game: strategic use of the administrative process”, published in 1978 and quoted in Ben Goldacre's important book Bad Pharma: How drug companies mislead doctors and harm patients (2012), provides useful insights into this very conscious influence strategy:

“Of course, there are also important tactical elements of lobbying. This is most effectively done by identifying the leading experts in each relevant field and hiring them as consultants or advisors, or giving them research grants and the like. This activity requires a modicum of finesse; it must not be too blatant, for the experts themselves must not recognise that they have lost their objectivity and freedom of action. At a minimum, a programme of this kind reduces the threat that the leading experts will be available to testify or write against the interests of the regulated firms.”13

Observations

Unacceptable. With 46%, the proportion of EFSA experts in a financial COI situation remains unacceptable. It is urgent the EU institutions intervene by demanding that EFSA ceases to appoint experts with such financial links to regulated companies. This must be accompanied by giving EFSA the means to attract good candidates. See Section III. Recommendations for more details.

Indifference in EFSA’s management? Many scientists with financial conflicts of interests have been re-appointed by EFSA, including in senior positions (chair, vice-chair, scientific committee). Among the members of EFSA’s 2015-2018 panels, 52% were already there in 2012-2015 but strikingly, the proportion of experts who had COIs in 2013 among these is almost exactly the same as the general proportion of experts with COIs in the 2012-2015 panels (59%). Independence doesn’t seem to have been a criteria when deciding whether to re-appoint former experts.

Some improvements. In all 2015-2018 panels, the proportion of experts in a financial COI situation has decreased (about 20% overall) except in Plant Health. The most significant reductions are observed in the NDA (Nutrition) panel and the Scientific Committee. This could be explained by an effort by EFSA to hire new experts with less financial links to industry, or a possible increase in omissions in the experts’ declarations of interest. The proportion of experts who do not have a declared conflict of interest has increased significantly too, but there is also an increase in situations which could not be assessed based only on the informations provided by the experts.

Direct and indirect conflicts of interests. 30.3% of EFSA experts are in an indirect financial COI situation (they belong to an organisation receiving more than 20% of its funding from regulated interests in the past 5 years), 26.5% in a direct financial COI situation (they have received money from regulated interests in the past 5 years) and more than 16% [20 June 2017 CORRECTION: the percentage is 10.9%] of experts have both direct and indirect financial COIs. EFSA’s draft new independence policy, whose only significant improvement is a ban on consultancy contracts, would only reduce the proportion of experts in a direct financial COI situation.

Growing awareness among scientists. Many EFSA experts now describe their interests from a perspective of independence from industry, which was rarely the case in 2013. This indicates a growing awareness among EFSA experts of the need to be independent from regulated companies to fulfil their mission.

Industry science. Certain scientific organisations whose funding primarily comes from industry often appear among expert interests, such as, in the pesticides panel14, the Society of Environmental Toxicology and Chemistry (SETAC). Interests linked to the International Life Sciences Institute (ILSI) generally stop mid-2012, which is when EFSA asked its experts to no longer participate in this lobby group’s activities15, but recent examples of EFSA experts participating to and even co-organising the lobbying events of ILSI have recently been described in the media16.

Privatisations. The case of semi-public or recently privatised research organisations (such as Fraunhofer, Rothamsted, Alterra and RIKILT at Wageningen University, TNO Triskelion, FERA Science...) is problematic. While these institutions come from the public sector, political decisions to privatise them or turn them into research services providers have made them more open to industry interests, some of them (like Fraunhofer or FERA) to a degree that led us to consider their employees on EFSA panels as in a situation of conflicts of interests. While steering public research institutions towards new marketable products reflects the current dominant research policy priorities in the EU, the possible impact on food safety of these policies has been overlooked and needs addressing.

UK. The UK stands out for the difficulty to find EFSA experts from this country who are independent from the private sector. The government privatised its own national food safety and environment laboratory in 2015, FERA17, which is now FERA Science Ltd and works for commercial clients too; and the private sector is largely steering the allocation of public research funds for research in agriculture and food, through extensive industry interests present at the Biotechnology and Biological Sciences Research Council (BBSRC)18.

Gender. There are 68,7% of men among EFSA experts, with the nutrition panel (NDA) the only one balanced19. Interestingly, among all EFSA experts 51% of men are in a COI situation while only 36,4% of the women are.

More than the panels. A member since 2006 of the Nutrition panel (NDA) who had many COIs in this position, Prof. H. Verhagen has been hired in 2015 by EFSA as its new Head of EFSA’s Risk Assessment and Scientific Assistance Department (RASA). Previously, he was working at the Netherlands’ National Institute for Public Health and the Environment (RIVM) and before that at Unilever; but he was also a member of the Publication Committee of ILSI Europe (until 2009), and a member of the Scientific Committee of the Ik Kies Bewust Foundation (IKB), part of a food industry front-of-pack labelling self-initiative called Choices International foundation, co-founded by Unilever.

II. Examples of financial conflict of interests for each main loophole in EFSA’s current and draft new independence rules

The main loopholes in EFSA’s current independence policy have been maintained in its draft new policy, published last April for a public consultation to which we contributed in great detail. Given the signals sent by EFSA’s management in our discussions with us and our long experience in following this file, we do not expect that the public consultation will have a significant impact on the draft.

2.1 Loophole 1: a deliberately narrow scope for assessing experts’ interests

Experts should have a 'cooling-off' period between having corporate / financial interests and advising EFSA. The European Parliament has made very clear that a two-years cooling-off period should be applied to all “companies whose products are assessed by the Authority and to any organisations funded by them”. We ask for a five-years cooling-off period.

But EFSA only applies a two-years cooling-off period selectively, to interests related to the specific topics dealt with by the scientific panel in question.

For years this loophole has been used by EFSA to keep appointing experts working with and/or funded by the food industry on its panels. All the conflicts of interest detailed here would not be prevented by EFSA’s draft new policy, which keeps the loophole wide open and argues, without any substantiation, that this should be done in order to “not hinder the availability of expertise needed to accomplish EFSA’s duties”.

EFSA has appointed as Vice-Chair of its panel on Biological Hazards Dr. B. Noerrung, whereas this expert is an ongoing board member of the Danish Dairy Research Foundation, where she gives advice to the Foundation on “the allocation of funding for new research projects” in the dairy sector.

The Danish Dairy Research Foundation is administered by the Danish Agriculture & Food Council, the trade association for the Danish farming and food industry, which has an office in Brussels, is recorded in the EU lobbying transparency register and declared between 500.000 and 599.000€ in lobbying costs in 2016.

On its food additives panel (ANS), EFSA has re-appointed Prof. D. Parent-Massin, a toxicology professor in the University of Brest, who was exposed in a major French TV news documentary for being briefed by a Coca-Cola executive before addressing doctors on aspartame, did consultancy work on several issues for the food industry (only before 2011 according to her DOI) and still works with the French fund for Nutrition and Health (FFAS), an organisation funded by the food industry who lobbied strongly20 against the new food labelling initiative of the French Ministry of Health.

On its panel on food additives (ANS), EFSA has re-appointed Dr. F. Aguilar (he was already on the ANS panel between 2012 and 2015), who declares that a “close family member” was and is an employee of Nestlé but as a “quality management system coordinator”, meaning the interest is “no single product related”.

But sometimes, EFSA does not even apply its own narrow assessment scope.

On its CEF panel (Food Contact Materials, Enzymes, Flavourings and Processing Aids), EFSA has appointed Prof. Dr. H. Zorn, Director of the Institute of Food Chemistry and Food Biotechnology of the Justus Liebig University in Giessen, Germany.

But this scientist also works for the Molecular Biology and Applied Ecology section of the Fraunhofer Institute, a very large contract research organisation in Germany which gets at least 35% of its funding from the private sector. He also worked as a consultant for the biotechnology company Artes Biotechnology, the Forschungskreis der Ernährungsindustrie (a research association of the nutrition industry), received research funding from Symrise (a fragrances and flavourings company) and Philip Morris International, and applied for a patent on an enzyme together with Nestlé.

This certainly reflects a successful career, but is it the best possible hire for making sure that the public risk assessent of, for instance, enzymes produced by Nestlé or Symrise, is the most independent possible?

Similarly, on its Scientific Committee, EFSA has re-appointed the Swiss toxicologist Dr. J.R. Schlatter. EFSA’s Scientific Committee has a very important task: it defines “harmonised risk assessment methodologies on scientific matters of a horizontal nature in the fields within EFSA's remit where EU-wide approaches are not already defined”. In 2012 then 2013, we already indicated to EFSA that this expert, who has been sitting on EFSA’s Scientific Committee since 2009, belonged to the Advisory board of the European Food Information Council (EUFIC), a Brussels lobby group of the food industry, and had been until April 2012 a member of the Board of Directors of the industry food lobby group ILSI (which precisely works on risk assessment methodologies).

Today, Dr. Schlatter still belongs to EUFIC, and to the International Society of Regulatory Toxicology & Pharmacology, an organisation linked to food and tobacco multinational companies. This association owns “Regulatory Toxicology and Pharmacology”, described as a “vanity journal that publishes mercenary science created by polluters and producers of toxic chemicals to manufacture uncertainty about the science underlying public-health and environmental protections” by David Michaels, professor of environmental and occupational health at the George Washington University School of Public Health.

Failing to close this loophole will keep generating new media scandals any time any journalist double-checks EFSA’s panel members’ interests.

2.2 Loophole 2: even when the nature of the interest coincides with the specific mandate of the panel the expert serves on, the sources of the expert's research funding are largely excluded as a potential conflict of interest.

In EFSA’s current independence policy, research funding is only taken into account when it is above 25% of the total research budget managed annually by the expert.

In EFSA’s draft new policy, research funding is completely excluded from the scope of the two-years cooling-off period. Research funding is, however, the largest source of financial conflicts of interest at EFSA (more than 40% in 2013).

Research funding is a well-known tool for corporate interests to influence public policy through influencing the knowledge which informs it21 (obvious examples include climate change, tobacco, asbestos, lead gasoline, sugar etc.). However, each of these experts was appointed in compliance with EFSA’s current independence rules and could still be under its draft new ones.

On its Pesticides panel, EFSA has appointed as Vice-Chair an expert (Dr. T. Brock) who currently receives research funding from the pesticides industry’s EU lobby group, the European Crop Protection Association (ECPA). We had already indicated in 2013 that this expert had been appointed in breach of EFSA’s current rules on chairs and vice-chairs as he was receiving research funding from the chemical industry’s EU lobby group, the European Chemical Industry Council (CEFIC). Dr. Brock has also been appointed on EFSA’s Scientific Committee.

Again on the CEF panel, EFSA appointed Dr. R. Franz. Not only is this expert also employed by the Fraunhofer Institute, but he is currently receiving research funding on nanomaterials from PlasticsEurope, the EU lobby group of the plastics industry and whose active lobbying against the EU’s attempts to regulate endocrine disrupting chemicals we have recently exposed.

Back in 2013, we had already indicated to EFSA that this expert, who was already employed by Fraunhofer, was already receiving research funding from PlasticsEurope.

On its Animal Health and Welfare panel, EFSA has appointed an expert (Dr. S. Edwards) who receives research funding from several different industry organisations and companies including: a trade group for the British pig industry called the British Pig Executive, the British supermarket chain Sainsbury’s, and an undisclosed “feed compounder” (animal feed ingredients) company.

In 2013, we had already indicated to EFSA that Dr. Edwards was receiving research funding from the British Pig Executive, but EFSA re-appointed this expert on the same panel.

III. Recommendations

→ Our first recommendation for a meaningful independence policy to be put in place is that EFSA’s Management Board takes the time to look at the reality of conflicts of interests in EFSA’s panels before taking its decision.

Having a reliable and credible food safety agency in the EU is in the interest of everyone, even the food industry. Clearly, the current system does not work and needs more than a marginal improvement.

A simpler, clearer policy along the lines we propose would heal EFSA’s reputation (and the EU’s...), but also help EFSA and its experts: the agency will save resources by no longer having to process a heavy and dysfunctional policy, and experts will no longer be criticised individually for EFSA’s mistaken recruitment decisions (the media treatment of conflicts of interests tends to echo that of cases of corruption, whereas the blame lies firstly in EFSA’s wrong recruitment decisions and policy).

→ At least, we suggest that EFSA respects the demands of the European Parliament, made again this year for the fourth year in a row:

“incorporate into its new independence policy a two-year cooling-off period for all material interests related to the companies whose products are assessed by the Authority and to any organisations funded by them”.

This means that EFSA should not hire any expert who would have received money from any company whose products are evaluated by the agency for the past two years. Nor, importantly, any organisation receiving money from such companies (this is very important as industry’s lobbying on these matters is often done via third parties such as ILSI, EUFIC etc.).

→ We suggest that the cooling off period is increased to five years.

→ This rule should have no exception and be applied across the board.

In particular, research funding should be included in the scope of the assessment of experts’ interests. EFSA’s draft new independence policy, which tries to exclude research funding, was strongly criticised by the European Parliament. It said it

“regrets that the Authority has not included research funding in the list of interests to be covered by the two-years cooling-off period, as the [Parliament] already identified in the latest discharge decisions; calls on the Authority to swiftly implement the measure in line with the [Parliament]'s repeated requests.”

The issue is not excluding the food industry’s expertise but avoiding undue influence on the EFSA’s decisions in a context where the Authority does not have the internal resources to develop its own research capacity. A strict cooling-off period on financial conflicts of interest combined with a systematic use of hearing experts (inviting the broadest range of experts, including those from industry, to dedicated hearings, but leaving the deliberation and writing phases of EFSA’s scientific opinions to experts without financial COIs) would enable EFSA to protect its integrity and access all the expertise it needs.

We also insist on the importance of managing financial and intellectual conflicts of interests differently22. Financial conflicts of interest are tangible, measurable, and their influence is well documented: excluding them from the panels would be a very clear and meaningful policy. But intellectual conflicts of interest, with the exception that experts should not be allowed to review their own work, are by nature impossible to avoid (we all have our own biases). Furthermore, the very principle of regulating individual opinions is dangerous for political rights. The most convincing approach to tackle the problem seems collegiality: making sure there is a diverse range of expertise and opinions available on the panel.

Independence at EFSA is a broader issue than the simple independence of experts, and it is clear that EFSA needs additional resources23 as well as the possibility to publish all the data it works with to enable a meaningful interaction on its work with the scientific community24. These objectives have already been formally adopted by EFSA and we support them entirely. But it seems rather obvious that no longer hiring experts with financial conflicts of interest needs to happen first if political support from the other EU institutions for these measures is to be found.

For a more detailed discussion and analysis of EFSA’s draft new independence policy, we refer our readers to our submission to EFSA’s public consultation on its draft.

- 1. “Unhappy Meal – The European Food Safety Authority's independence problem”, Corporate Europe Observatory & Stéphane Horel, October 2013 http://corporateeurope.org/efsa/2013/10/unhappy-meal-european-food-safet...

- 2. All our raw data, with the panel-by-panel analysis and the assessment of each individual interest declared by experts, is available on request.

- 3. The current panels have been appointed from three years, from July 2015 to July 2018. Our assessment is based on Declarations of Interest downloaded on December 2 2015.

- 4. All Declarations of interest were downloaded on December 2 2015. We are very grateful to the French collective Regards Citoyens for their competent help in scraping the pdfs.

- 5. EFSA requests its experts to disclose their interests in the past 5 years, and we defend a 5-years cooling-off period for all financial interests in regulated companies for EFSA experts (see III. Recommendations).

- 6. We did not consider that membership of scientific societies sponsored by industry was a financial COI, with certain exceptions for industry-driven groups such as the International Life Sciences Institute (ILSI). Positions of responsibilities in sponsored scientific societies (president, treasurer, member of an advisory committee or organising committee), however, was considered an indirect financial COI.

- 7. Given that EFSA works with external experts and that most scientific societies rely on private sponsorship to organise their events, 0% was not realistic. We thought 20% was a reasonable threshold.

- 8. This also applies to experts whose relatives are employees of, or receive significant funding from, regulated companies.

- 9. With the exception that experts should not have a decision-making power when it comes to the evaluation of their own work.

- 10. Fineberg HV. Conflict of Interest, Why Does It Matter? JAMA. 2017;317(17):1717-1718. doi:10.1001/jama.2017.1869

- 11. As it remains valid today, this section is adapted from a section of our previous EFSA assessment, “Unhappy Meal” (op.cit.)

- 12. Stigler G. 1971. The theory of economic regulation. Bell J. Econ. Man. Sci. 2:3-21.

- 13. Owen BM, Braeutigam RR. The regulation game: strategic use of the administrative process. Ballinger Pub. Co., 1978. Via Goldacre B. Bad Pharma: How drug companies mislead doctors and harm patients. Fourth Estate, 2012

- 14. Given the current debate around glyphosate, it is worth reminding that EFSA’s Pesticides panel does not deal directly with pesticides authorisations, but does play a strong role in defining risk assessment methodologies for pesticides in the EU.

- 15. Following the 2012 Banati scandal, EFSA asked its experts to leave their ILSI positions if they wanted to continue working with the agency.

- 16. These ILSI interests have been declared by the experts concerned in their updated DOIs on EFSA’s website.

- 17. It appears from the recent DOI of a FERA expert (R. Martin) that “Fera Science Limited has maintained Article 36 (and so Food Safety Organisation) status, on the grounds that the funding profile for Fera Science Ltd is dominated by public sector funding, at least in the medium term.” This is not justifiable given FERA’s new structure and ownership, and EFSA must remove FERA from its list of Food Safety Organisations (granting extended privileges to their employees within EFSA).

- 18. BBSRC is a public UK research funding body, whose budget comes entirely from the Department for Business, Innovation and Skills of the UK government, with extensive business funding programs. Its governing council includes several industry executives.

- 19. We did not check to what extent this gender imbalance differed from the gender balance in the respective research fields at stake.

- 20. Scandale autour de l’étiquetage alimentaire, Le Monde, S. Horel & P. Santi, July 2016, http://abonnes.lemonde.fr/planete/article/2016/07/08/scandale-autour-de-...

- 21. It's Not the Answers That Are Biased, It's the Questions – David Michaels, Washington Post, July 2008 http://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-dyn/content/article/2008/07/14/AR200807...

- 22. See in particular Bero L. Addressing Bias and Conflict of Interest Among Biomedical Researchers. JAMA. 2017;317(17):1723-1724. doi:10.1001/jama.2017.3854

- 23. EFSA experts are paid a financial compensation (385€ per day of panel attendance plus expenses), but not to a level which would enable them to work only for EFSA. According to EFSA’s Director, national food safety organisations are increasingly reluctant to send their experts work at EFSA. Giving EFSA the means to financially compensate these organisations for their experts’ time at EFSA could be an option.

- 24. This impossibility to use industry-owned data for scientific publications whereas most of EFSA’s work relies on such data means that it is difficult for EFSA to attract young scientists, who need to publish to advance their career.