Veto power to please lobbyists – corporations behind Commission power grab over services

New documents increase concerns over the controversial reform to the Services Notification Procedure (“Bolkestein Directive”), which could radically expand EU Commission powers over national and municipal services regulation: 55 files obtained via access to documents requests show the heavy influence of big business lobbies over the proposal. The next negotiation round on the proposal is imminent - a deal would constrain democratic decision-making in member states on everything from housing, to water and local planning.

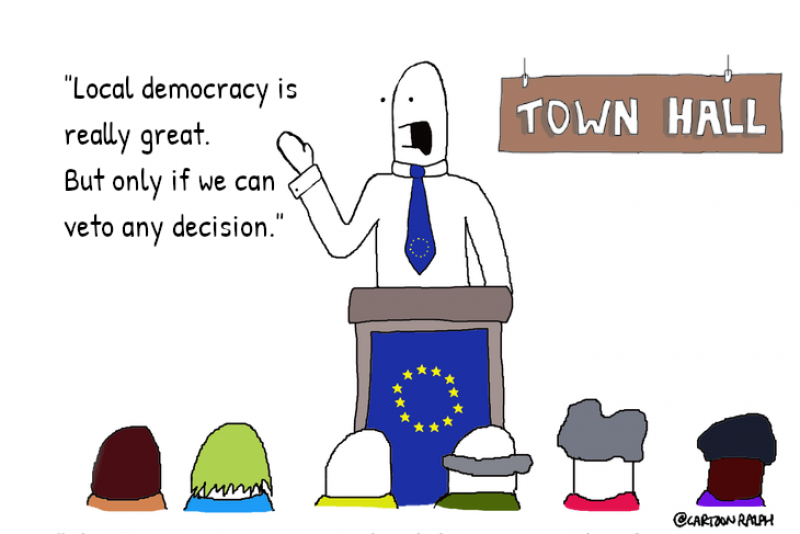

Opposition is growing over the European Commission’s proposed Services Notification Procedure. This directive threatens to undermine local democratic decisions, and constrain public interest policy-making in a wide range of sectors, including city planning, education, affordable housing, water supply, energy supply, waste management, and many others. The proposed directive is part of a wider Services Package (a follow-up to the 2006 Services Directive, also known as the Bolkestein Directive which provoked mass protests in several EU countries due to concerns about its social impacts and was only approved after being scaled down).

Many, from city councils to trade unions, have expressed alarm at the sweeping new powers the draft directive will give the Commission. It will be able to annul new laws and regulations developed by national parliaments, regional assemblies, and local governments across Europe, or impose significant delays in order to change proposals. Those authorities will have to submit their regulations to the Commission three months in advance, in order to receive prior approval; a far-reaching tightening of existing rules, which only allows the Commission to object after the approval, and as a last resort to take the matter to the European Court of Justice. And the scope is overwhelming: according to recent information from the Commission, 79 different sectors – including child care, energy, water supply and 76 more – were covered by notifications between 2010 and 2015. New documents obtained by Corporate Europe Observatory now confirm that, in drafting the proposal, the Commission has taken its cues from the corporate lobby groups who will benefit most, whilst largely ignoring concerns raised by other interests.

Because of these growing concerns, last month a coalition of more than 160 civil society groups, unions, mayors, and progressive parties running major European cities wrote a protest letter to the Romanian EU Presidency, rejecting the proposed directive as it “would reduce space for progressive policies, including at local level” and because it is “disproportional and at odds with the subsidiarity principle”.

In response to freedom of information requests by Corporate Europe Observatory, the Commission has released over 55 documents, including emails, letters, position papers, and minutes of meetings between Commission officials and lobbyists on the Notifications Procedure.1 The documents reveal a very intimate working relationship between the Commission department responsible for the Notifications Procedure and three major industry lobbying groups: BusinessEurope, EuroCommerce, and EuroChambres. Industry has been particularly keen on shaping the proposal, which will give it a ‘backdoor’ channel to comment on – and lobby against – local legislation before it is enacted.

The Commission’s proposal for the Notifications Procedure is fully in line with the wishes of these three corporate lobby giants, despite the fact that numerous other organisations – including associations of architects, engineers, and free professions, as well as trade unions – heavily criticised the proposal. The European Commission has essentially treated BusinessEurope as a strategic partner in promoting the deeply neoliberal Notification Procedure, for instance holding a closed-door session with them alone during the negotiations to strategise on the way forward. This is in stark contrast with the way the Commission has responded to many of its critics: with deafening silence.

The Commission’s big business allies

If passed, the reform of the Directive would give corporations whose profits can be affected by local, regional or national legislation, advance warning to complain directly to the Commission. (See box below, When is a social policy a business ‘obstacle’?) It is no surprise, then, that the proposed reform closely mimics suggestions made by Brussels’ most powerful corporate lobby group, BusinessEurope. Already in December 2014, a few months after the Juncker Commission took office, BusinessEurope complained to the Commission that public authorities have “too much leeway” in implementing the Bolkestein Directive. The “large area of discretion” creates a “grey zone”, BusinessEurope argues, demanding far stricter notification obligations for new regulations and measures affecting services companies.2 In a September 2015 letter on the Single Market Strategy, the industry lobby giant asked the Commission to “enhance the effectiveness” of the existing light notification procedure that was introduced with the 2006 Bolkestein Directive.3 “Any new laws, regulations or administrative provisions” impacting on services companies “should be assessed by the Commission on their compatibility with EU law”, BusinessEurope wrote, demanding a “standstill period” in decision-making while the Commission assessed the new provisions.4

When the Commission launched its proposal in January 2017, BusinessEurope reacted with a press release expressing its support and welcoming the “focus on removing regulatory barriers where we can. A better notification procedure will help to avoid new obstacles”.5 In April 2017 BusinessEurope released a more detailed position paper. In a letter to Director-General Lowri Evans, BusinessEurope expressed strong support for “the novel approach that the Commission has taken” and welcomed the “bold methods”.

The position paper praises the Commission for its decision “to move beyond the classic line of ensuring better implementation” of the Services Directive and its proposals to “remove remaining administrative, regulatory and other barriers… as well as to avoid the introduction of new obstacles”.6 The problem is that much of what BusinessEurope considers to be barriers and obstacles are in fact legitimate and much-needed social and environmental policies, democratically decided and introduced to protect the public interest.

When is social or environmental policy a business ‘obstacle’?What ‘obstacles’ are BusinessEurope referring to? All too often they mean social policy proposals that could affect corporations’ business models. Take these hypothetical examples under the new directive:

|

The released documents show that BusinessEurope has been Commission’s closest partner in promoting the Notifications Procedure, but the Commission also received support from two other corporate lobby groups EuroCommerce, and EuroChambres.

In a report from a February 2017 meeting with EuroCommerce, a Commission official reported that, “As to the notification proposal, Eurocommerce is very supportive”.7 The report from the meeting highlighted specific demands raised by EuroCommerce, for instance that “failure to notify should be followed by a serious sanction”. In its position paper, EuroCommerce stresses the elements of the Commission proposal that it considers particularly essential, including that “retail establishment authorisations procedures should be included in the scope (Art. 4)”.8 EuroCommerce clearly sees the proposed directive as a tool for avoiding restrictions on the activities of its member firms, which includes large supermarket chains. In quite a few EU countries, local regulations have been introduced that limit new large-scale out-of-town hypermarkets, in order to protect small shops.

The third cheerleader for the Commission’s proposal is EuroChambres, the Association of European Chambers of Commerce and Industry. In an email preparing a spring 2017 meeting with the Commission, EuroChambres suggested focusing on “issues such as how stakeholders can capitalize on the new approach to notifications of changes in services requirements”.9 This refers to a very dangerous element of the proposed directive: giving ‘stakeholders’ (in practice lobbyists) formal access to and right to comment on the rules notified by governments and municipalities. During the meeting, which was also attended by chambers of commerce from ten EU countries, EuroChambres asks for clarification: “how exactly will stakeholders get access to notifications, what exactly will they have access to and how can they provide comments?”. The Commission responded that “initial notification, supporting documentation and final adopted measure will be shared with interested stakeholders via online interface, that will also provide for an option for stakeholders to provide comments.”10

The Commission’s alliesBusinessEurope is a lobby group representing both national employers' organisations and numerous large multinational corporations. BusinessEurope reported spending over four million euros on lobbying in 2017, involving 30 full-time lobbyists, of which 25 have a permanent access pass to the European Parliament. EuroCommerce is the lobby group for the retail sector and other trading companies, with members including British Retail Consortium and French Retail Association, as well as Carrefour, Amazon, Tesco, IKEA, Lidl, METRO and other supermarket chains. Eurocommerce reported spending up to €1.5 million on lobbying in 2017, and has 18 lobbyists with EP accreditation. Eurochambres reported spending €1,400,000 on lobbying in 2017, employing 20 lobbyists, out of which 5 lobbyists with EP accreditation. |

Small businesses and labour unions slam the Commission’s proposal

While the released documents show BusinessEurope, EuroCommerce, and Eurochambres’ jubilation and full support, virtually all other feedback on the Commission’s proposal was negative. This included strongly worded criticism by more than a dozen associations of engineers, tax advisers, architects and free professions, as well as Confcommercio, representing Italian small businesses engaged in commerce, tourism and services. These organisations all consider the Commission’s proposal a violation of the EU’s subsidiarity principle by excessively intervening in national level decision-making and even altering the division of powers between Commission and member states. The requirements to notify in advance of deciding new regulations and allow the Commission to demand changes will, as several associations point out, create excessive bureaucratic hurdles. Confcommercio told the Commission that it disagrees “entirely with the principle that any national or local regulatory measures concerning authorisation schemes and requirements for services should undergo assessment by the Commission before their adoption”.11

Remarkably, the Commission appears not to have responded to this criticism. Among the 50+ documents, there are numerous responses to letters from BusinessEurope, EuroCommerce, and EuroChambres, but none to the small business critics. Trade union federations EPSU and ETUC also expressed strong concerns, for instance that the proposal may lead to “a ‘chilling effect’ for new regulations that are necessary” and expressed specific worries about the impact on regulation of care services.12 The unions asked the Commission to provide more information to enable them to assess what types of services regulation would be likely impacted by the proposal. The Commission rejected this request, arguing that the Services Directive does not allow them to release this information to stakeholders.13

A torrent of criticismThe Commission’s proposal was heavily criticised by the Architects’ Council of Europe (ACE), who point out that there already exists “a perfectly adequate procedure foreseen for 'worst cases' eg where a member state adopts a measure that is in contradiction with the Services Directive (Decision to require abolition of a regulation / infringement procedure)”. The architects’ association also debunks the Commission’s line that member state authorities don’t understand the Services Directive: “the fact that – according to the proposal – the European Commission would be able to require the repeal of a measure that has not been notified, implies that the European Commission seems to know better than the Member State itself which national measures fall under the scope of the Directive). On the contrary, ACE believes that a vast majority of Member States are very well aware of the requirements of the Services Directive but do not always share the compliance assessment of the European Commission.” |

A flawed consultation

In a recent article Professor Alberto Alemanno points out that the EU’s public consultations are typically, “top-down exercises that only involve a few actors and fail to engage the individuals and groups that will be most affected by the policy under discussion.” The public consultation on the Notification Procedure held in spring 2016 is a case in point. Out of the 126 replies submitted to the consultation, 107 came from organisations, and the rest were from individuals. Among the groups, 75 per cent were business/representatives of business and 25 per cent were public authorities (mainly government ministries). The Commission has failed to publish the submissions to the consultation on its website, contrary to its stated standard practice. The Commission’s own rules require it to publish individual consultation responses online.14 CEO repeatedly reminded the Commission of this transparency failure and eventually submitted a freedom of information request.

In response to the FOI request, the Commission released a list of companies and organisations that participated in the consultation. The list shows that a very large part of the respondents were from Poland and Lithuania, but more importantly: only four municipalities (three Lithuanian, one Polish) and seven regional authorities (two Italian and one Lithuanian, as well as four ministries from German Bundesländer) were included in the consultation. Not a single larger city was included, nor were any of the EU-level federations of municipalities. This is a remarkable failure, considering the far-reaching impacts the proposed directive would have for municipalities (who would have to seek the Commission’s advance permission for any decision related to the services sector). The Commission, more generally, failed to secure input from a broad range of stakeholders, and it appears that only one trade union and no other civil society groups contributed to the consultation.

Considering how controversial the 2006 Services Directive (also known as the Bolkestein Directive) was, the Commission should have actively approached organisations with an interest in regulations of the services sectors, whether or not they were likely to be critical of the Commission’s plans. The Commission’s own rules instruct officials “to consult broadly and transparently among stakeholders who might be concerned by the initiative, seeking the whole spectrum of views in order to avoid bias or skewed conclusions (“capture”) promoted by specific constituencies.”15 This appears not to have happened for the Notification Procedure directive.

But not only was there a failure to properly reach out to ensure the views of affected stakeholders were included, those critical voices that did contribute to the consultation (including associations representing engineers, architects, and tax advisors) appear to have been given little attention. In letters to the Commission, several of the groups indicate that critical voices were not taken into account in the official online consultation and therefore questioned whether the Commission actually has a mandate for the kind of Notification Procedure proposal it has developed.16

Big business gets impatient

In December 2017 the European Parliament’s internal market committee approved the Commission’s proposal with only minor changes. By February 2018 decision-making had entered the final stage with trilogue negotiations between Commission, Parliament, and EU governments (Council). BusinessEurope clearly expected this last phase to be fast and smooth, and showed great impatience when this was not the case. In May 2018 after three months of trilogue negotiations, BusinessEurope wrote to Commissioner Bienkowska to complain.

BusinessEurope Director Markus Breyer told Bienkowska that “it is very worrying that the trilogues on the last bit of the package, the proposal on Notifications in Services, seem to have a bumpy road”. Breyer insisted, rather dramatically, that “Businesses need a positive signal, now,” and added, “we call on the co-legislators to adopt the proposal on Notifications in Services at their next trilogue,” to “deliver the deal still before the summer break”.17 Responding on behalf of the Commissioner, Directorate General GROW’s Hubert Gambs assured Breyer, “that the various legal and policy points set out in your letter are well noted and will be carefully considered by the Commission. My colleagues and I will continue our efforts to achieve an ambitious result”.

In early June 2018 BusinessEurope wrote to all EU governments with a “Call for a deal on the proposal on Notifications in Services before the summer break”. When this deal didn’t happen, they tweeted: “Co-legislators disappoint business community in their 3rd trilogue by failing to agree on the Notifications in #Services as administrative tool to prevent new regulatory barriers for service providers”. That same month the Commission met with a large group of BusinessEurope lobbyists in a closed-door session on the Notification Procedure. The meeting report mentions that discussions focused “on what could be done in the future (including on enforcement) and the role of BusinessEurope in this regard.”18

EuroCommerce also wrote to the Commission about what they considered to be overly slow progress in the trilogue negotiations: “Perhaps a bit unorthodox, but here are some ideas regarding the last proposal of the Presidency”. Their “ideas” were about how to organise the notifications by regions and municipalities (directly or via national governments).19

Clearly, this proposal was not only pushed by industry lobby groups, the Commission was keen on giving them special treatment from day one: the consultation that provided the raw material for the draft directive was biased, the draft mirrored the ideas developed by big business lobby groups, and the Commission was keen on strategising with industry when the debate took off. All along, the European executive paid little attention to other voices.

Neoliberal tunnel vision

Negotiations on the Notification Procedure, led by the Romanian EU Presidency, may be completed within months. Fortunately, a number of governments have so far refused to go along with the proposal and want to restrict both its scope and the Commission’s powers. The proposed directive is the result of the European Commission’s neoliberal tunnel-vision. Democratic decision-making – including at the municipal level – is seen as an obstacle to the end-goal of an EU-wide ‘free market’ in services, which should therefore be reigned in and controlled by the Commission.

The directive is so flawed that only self-interested big business lobby groups defend it. Opposition to the directive is growing rapidly, ranging from city councilors from Barcelona, Amsterdam and Napoli, over some of Europe’s largest trade unions to civil society groups from across Europe. For the future of democracy in Europe, one can only hope that the negotiations fail to deliver a deal and that this ill-conceived directive is dropped altogether.

- 1. In September 2018 Corporate Europe Observatory submitted a freedom of information request (correspondence and minutes of meetings between Commission and lobbies), and after lots of delays from the Commission’s side, documents were released on 22 November 2018. The FOI request is online here: https://www.asktheeu.org/en/request/5964/followups/new/19208?post_redire... A follow-up request submitted in December 2018 resulted in an additional 6 documents being released. This FOI request and the documents are online here: https://www.asktheeu.org/en/request/the_eu_notification_procedure_fo?pos...

- 2. BusinessEurope sent the Commission its strategy paper “Remaining obstacles to a true single market for services” on December 17 2014.

- 3. Under the existing legislation, public authorities need to notify the European Commission after decisions about new regulations have been made. The European Commission can start an infringement procedure (including a possible court case at the European Court of Justice) if it considers new regulations to violate the Services Directive.

- 4. BusinessEurope’s contribution to the upcoming Internal Market Strategy for Europe Priorities and recommendations for a better functioning single market”, 28 September 2015. https://www.businesseurope.eu/sites/buseur/files/media/position_papers/i...

- 5. BusinessEurope press release 10 January 2017: https://www.businesseurope.eu/publications/timely-services-package-europ.... A few weeks later, a Commission official came to BusinessEurope to present the Services Package to members of the organisation. BusinessEurope sent a thank you letter stressing “the open exchange of views with members on the notification procedure”.

- 6. BusinessEurope announced that it would be actively lobbying MEPs and governments to support the Commission’s proposal: “Naturally we will also be engaging actively with the EP and at Council level (where of course we are already discussing)”. Email BusinessEurope to European Commission DG GROW, April 27 2017.

- 7. Report meeting Eurocommerce 9/2 2017, 23 February 2017.

- 8. Position Paper Services Notification Procedure, May 2017.

- 9. Email from EuroChambres to the European Commission, February 15 2017.

- 10. Services Notifications – Meeting with Eurochambres, 10 March 2017.

- 11. Services Package 2017: remarks on the proposals for EU directives.

- 12. Email from EPSU to the European Commission 16 May 2017.

- 13. EPSU, in their email of 16 May 2017, pointed out that the Commission’s impact assessment contained “very few concrete references to actual regulations that are unjustified and disproportionate [..] Would other soucrs of information be available”. The Commission responded that “it is legally not possible […] to sharewith you ad hoc documentation on specific notifications”. The Commission did offer the unions to meet and discuss their concerns. Email from the Commission to the ETUC and EPSU, May 29 2017.

- 14. See the European Commission’s “General principles and minimum standards for consultation” (May 2015): https://ec.europa.eu/info/sites/info/files/better-regulation-guidelines-...

- 15. See the European Commission’s “General principles and minimum standards for consultation” (May 2015): https://ec.europa.eu/info/sites/info/files/better-regulation-guidelines-...

- 16. Statement by the European Tax Adviser Federation ETAF on the proposal for a Directive on a notification procedure for authorisation schemes and requirements related to services. 18 M

- 17. Letter from BusinessEurope to the Commission, 3 May 2018.

- 18. Minutes from meeting with BusinessEurope's Internal Market Policy Committee, 26 June 2018

- 19. Email from EuroCommerce to the Commission on the trilogue services negotiations, 14 June 2018. Eurocommerce also said: “You could make it optional. If a MS wants to notify directly to the Commission that should be possible (by default). The alternative reporting (for municipalities) should be optional. It should be this or that, not both.”