Stay always informed

Interested in our articles? Get the latest information and analysis straight to your email. Sign up for our newsletter.

Big Tech might be the EU's biggest lobby spender by sector, but a little-known band of economic consultancies are still managing to fly under the radar on behalf of their tech clients. These consultancies are effectively 'spamming the regulator' with supposedly neutral reports to influence the EU's competition policy and smooth the path for Big Tech monopolies and mergers. What's worse, the Commission's DG Competition in charge of competition policy enjoys a regular revolving door with these consultancies.

Big Tech monopolies are defending their interests in the shaping and implementation of the EU's competition policy with the help of so-called 'economic consultancies'. While firms like Charles River Associates are unknown to the public, and their 'economic expertise' is presented as neutral, their behind-the-scenes impact on behalf of their Big Tech clients is considerable, in particular when it comes to EU merger control.

Big Tech is the biggest lobby sector in the EU by spending, ahead of pharma, fossil fuels, finance, or chemicals. And a significant part of that powerful lobbying firepower in Brussels is wielded by Google, Amazon, Meta (formerly Facebook), Apple, and Microsoft (known as 'GAFAM'). Together, GAFAM spends more than €26.5 million on influencing the EU institutions. And that's not all: Big Tech also wields considerable lobbying power in member states' capitals. For example, GAFAM spends €9.3 million defending its interests in Berlin, according to the German transparency register.

Big Tech’s political clout has grown alongside its ever-increasing market power, creating the risk that it has grown “too big to regulate”. Digital giants have used their economic power and monopoly position to systematically violate laws and their enforcement, impose unfair conditions on users and small businesses, and lobby for favourable legislation legitimizing their often unethical – and in some cases illegal –business models. Big Tech companies such as Meta have effectively run a “copy-acquire-kill” strategy with its competitors, resulting in ever-more market concentration. Meanwhile regulators have barely intervened to block any of these mergers. According to the former Chief Economist at DG Competition GAFAM has acquired more than a 1,000 firms in the last 20 years. Of the mergers examined, the European Commission has not even blocked one.

Big Tech’s monopoly power

Big Tech has almost become synonomous with monopoly power. Just a few companies have taken over large parts of the internet in markets as varied as online advertisements, e-commerce, social networks, online apps, navigation, video sharing, search, e-mail and the cloud. Tech corporations have used mergers and acqusitions to “gain market power, acquire data, and snuff out any threats from would-be competitors.” For example, Amazon has used its market power to ‘self-preference’ its products and use third party seller data to copy popular products. Simalarly, Google Search market share is close to 90 percent. It’s ranking algorithm determines the information billions of people see.

The NGO American Economic Liberties Project has documented 616 mergers and acquisitions by Amazon, Apple, Meta and Google over the years. Google alone has bought up 270 companies since 2001 or 13 mergers and acquisitions a year. A report by the US competition authority FTC shows that this is even an underestimation documenting 627 transactions in the period 2010-2019.

However, with the recently approved Digital Markets Act (DMA) Big Tech market power has come under public and regulatory scrutiny in Europe. But key questions which will decide the effectiveness of the regulation are still in the air, and these are a target for continued lobbying from Big Tech and its allies.

The Silicon Valley tech monopolies' are making heavy use of so-called economic consultancies, whose activities take place below the radar of public scrutiny. These consultancies, such as Compass Lexecon, Charles River Associates, Oxera, and RBB Economics, offer their clients analysis of economic issues, generally for use in public policy debates, legal and regulatory proceedings, and strategic decision-making. Hence these specialised consultancies play an important role in the field of EU competition policy, and are acting as a real vector for Big Tech influence. They represent their clients in front of the courts and provide reports for submission to DG Competition when it comes to mergers. They also write studies funded by clients to influence legislation and organise key debates and events in the EU’s capital on competition policy in general. They thus work to shape how competition policy enforcement looks in practice.

More spotlight on the lobbying role of economic consultancies is urgently needed. Even though at least some of the wider influencing activities listed in this article should be registered, they don’t appear in the EU’s Transparency Register, they don’t respond to requests, and the reports they provide to DG Competition in the interest of their clients are not disclosed to the public. Even the titles of these reports are unknown. We need a paradigm change that ensures more transparency, both on the influencing activities of economic consultancies and for the way EU competition policy is done in general (read the letter here send by 18 civil society organisations to Commissioner Vestager).

A closed 'expert' community

Big Tech has in particular relied on specialised economic consultancies to provide them with favourable economic arguments and studies to legitimise mergers to regulators, and 'prove' they are not harming consumers, or that their business behaviour is not abusive. In other words, they provide the arguments in the guise of 'neutral expertise', for why Big Tech monopoly power is allowed to grow further.

As the Directorate-General for Competition is required to take all submissions into account when looking into a merger case, these consultancies and their clients have obtained a semi-official position guaranteeing privileged access.

While these firms like to present themselves as neutral intermediaries who deliver valuable policy input to the EU’s anti-trust policy, they have a vested interest in acting on behalf of their clients. These firms not only engage in traditional lobbying activities (see below), but they also ‘spam the regulator’ with economic studies, have a strong foothold in EU expert groups, and appear to be on the lookout to hire former employees from DG Competition or other EU member states competition authorities.

Economic consultancies: a growing presence in the EU

The field of competition economics is dominated by a few consultancies: Compass Lexecon, CRAI, Oxera, and RBB Economics. The footprint of these firms has been steadily growing: with a combined turnover of at least €34.6 million in 2021 (up from €27.9 million euros in 2018), and 59 people working on EU policies, these firms have a substantial presence in the EU bubble.1

Despite their growing presence and their role both in advocacy, there is no information on economic consultancies available in the EU Transparency Register. The only firm that is potentially covered is Compass Lexecon as a subsidiary of FTI Consulting. FTI Consulting is the third largest lobby actor in the EU according to lobby expenses.

Compass Lexecon is a subsidiary of the lobbying firm FTI Consulting. According to their website, Compass Lexecon has worked for “84% of the current Fortune 100 companies”. Their presence in Brussels has been increasing. While they employed 15.4 people (full-time equivalent) in 2018, they now employ 27.2 FTE staff members. Their turnover has gone up from €13 million in 2018 to €15.5 million in 2021.

Big Tech cases Compass Lexecon has been handling include the Google/Fitbit merger, the IBM/Red Hat merger, Microsoft-Yahoo, the Uber court cases against EU member states, Apple and Irish state aid, Amazon/MGM, and Qualcomm.

Charles River Associates International (CRAI) is an American consultancy with a total revenue of €535 million in 2021. CRAI is largely owned by investment funds including BlackRock, Vanguard Group, Dimensional Fund Advisors, and FMR LLC. The turnover of its Brussels office has gone up from €2.6 million in 2018 to €4.4 million in 2021.

Its Big Tech cases include Google (French antitrust probe), Apple (French antitrust case), the Microsoft/Github merger, the Microsoft/LinkedIn merger, and Microsoft/Nuance merger

Oxera is based in the UK with subsidiaries in France, Germany, Italy, the Netherlands, and Belgium. Their total turnover is €45.3 million with a total of 176 employees. €19.2 million of their turnover is realized outside of the UK, but unfortunately there are no numbers available for their Brussels office.

Big Tech cases include Google Shopping (an abuse of dominance case), and Microsoft.

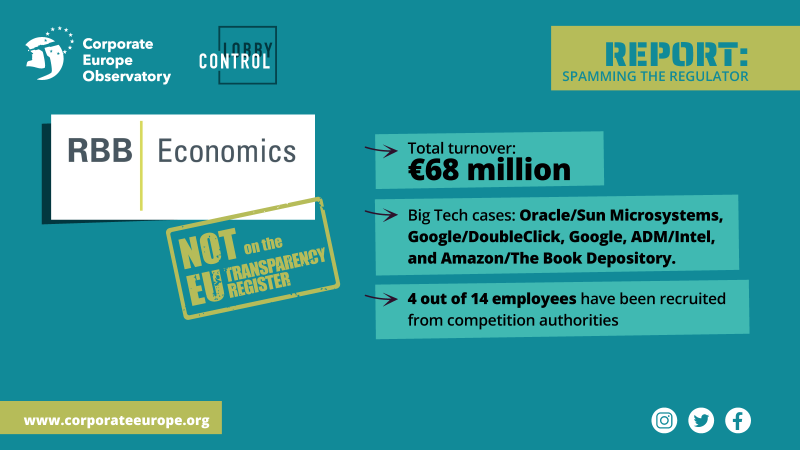

RBB Economics is based in the UK with offices in eight other countries. It has a turnover of €68 million, with 60 percent realized in the European Union. Their presence in Brussels has grown in the last years from 10.6 full-time employees in 2018 to 14.7 in 2021. Their turnover has also increased, from €12.3 million in 2018 to €14.7 million in 2021.

Big Tech cases include Oracle/Sun Microsystems, Google/DoubleClick, Google (abuse of dominant position case), ADM/Intel, and Amazon/The Book Depository, Google (abuse of dominance case).

1These numbers exclude Oxera as there are no numbers on its Brussels presence available.

Spamming the regulator

When the EU Commission approved the Google-Fitbit merger in December 2020, the decision was received with widespread condemnation. Fourteen competition economists, including three former chief economists of competition agencies, warned the Commission against the merger for “set[ting] tech enforcement back a generation”. Consumer groups, health experts, and data protection organisations, including the European Data Protection Board, all voiced serious objections against giving the already-ubiquitous Google access to the health, sleep, and location data of millions of users.

Not everybody was unhappy with the Commissions’ decision however. Economic consultancy Compass Lexecon proudly proclaimed it had “provided economic advice to Google during [the] merger proceedings”. The following year the firm won the award for Merger Control Matter of the Year from Global Competition Review for getting the Google-Fitbit merger approved. According to Compass Lexecon it had provided crucial economic arguments in proving that “[Fitbit’s data] was not unique and of limited value to Google”.

Economic consultancies have privileged access to these proceedings as they provide ‘expert’ economic submissions on behalf of their clients. This privileged access point has provided room for a novel lobbying strategy: spamming the regulator.

Merger investigations by competition authorities are an exceptionally closed process with almost no input from civil society. Economic consultancies have privileged access to these proceedings as they provide ‘expert’ economic submissions on behalf of their clients. This privileged access point has provided room for a novel influencing strategy: spamming the regulator.

Voices from within the Commission have pointed to a practice of submitting so many economic assessments that DG Competition has difficulty managing the workload. As DG Competition is obliged under the right to be heard to consider every expert submission, this tactic pushes the internal capacity to the limit and puts the regulator on the defensive.

Former Chief Economist Tommaso Valletti has been especially critical of the practice in an interview with the NGO Balanced Economy Project: “I saw the consultants hijack a certain way of doing economic work. They do this on a massive scale, to create doubt. They bombard you. They say ‘well, this merger could bring all these fantastic efficiencies: here is a possibility you should consider.’ You know that in practice this will not play a role, but then you have the burden of proof as an authority to dismiss those claims. It is a very dirty game." [emphasis added]

An unpublished paper, co-written by a current member of the Chief Economist Team at DG Competition, has termed this new lobbying strategy ‘spamming the regulator’. The writers highlight that due to the many submissions made by economic consultancies, “the regulator may decide not to rule against the firm and their merger, to avoid being challenged in court on procedural grounds”.

The paper shows how corporations are hiring more consultancies to spam the Commission with more submissions. From 2005 to 2020, both economic firms involvement in, as well as submissions to, merger cases have more than doubled. At the same time according to this paper, the quality of these submissions has dropped. In one case, the Commission remarked that answers from economic firms were “often laconic and unsubstantiated”.

These strategies are all the more effective as the revolving door between DG Competition and these economic consultancies guarantees detailed internal knowledge about the way DG Competition operates.

The revolving door between DG COMP and economic consultancies

The number of DG Competition officials passing through the ‘revolving door’ risks creating conflicts of interest and the development of a shared mindset on competition policy between those making policy and those trying to influence it. Several high-level cases in particular have shone the spotlight on former DG Comp officials joining the private sector: in 2021 two former Deputy Directors-General of DG Competition Carles Esteva Mosso and Cecilio Madero respectively joined the law firms Clifford Chance and Latham & Watkins, prompting the European Ombudsman to pay specific attention to the two officials in its inquiry into revolving doors. The European Ombudsman has moreover pointed to “the corrosive effects of officials bringing their knowledge and networks to related areas in the private sector”.Green MEP Daniel Freund remarked in a press release that “we have seen too many revolving door cases of... EU competition lawyers changing sides at court from suing Apple to defending Apple”.

This is however only the tip of the iceberg. The four firms mentioned here all have former officials from DG Competition or national competition authorities on their payroll. Out of 8 current employees at the Brussels office of CRAI, 2 have been recruited from competition authorities, 5 out of 21 employees at Compass Lexecon have a past as competition officials, 3 out of 9 at Oxera and 4 out of 14 at RBB Economics.

An inquiry by the European Ombudsman has pointed to “the corrosive effects of officials bringing their knowledge and networks to related areas in the private sector”.

Philip Lowe, a partner at Oxera, was for example the former Director-General at DG Competition. Miguel de la Mano, a former Head of Unit at DG Competition, joined Compass Lexecon in 2015 as an Executive Vice President and in 2022 as a partner at RBB Economics. Very problematically, according to his CV he worked on cases involving the digital giant Qualcomm at both at the Commission and Compass Lexecon.

Some of these officials pass through the revolving door several times. For example Stéphane Dewulf started his career at LECG Consulting and RBB Economics, before joining DG Competition as a case handler in 2014. In 2020 he passed again through the revolving door to join Oxera as Principal. Oxera’s press release following the move touted his experience as a former DG Competition official as a selling point, stating that “we believe [Dewulf’s] experience as consultant and ex-enforcer will be particularly appreciated by our clients”. Another case is Gregor Langus who joined the Chief Economist Team at DG Competition in 2007. In 2011, he became a senior consultant at Charles River Associates and in 2014 a senior Vice President at Compass Lexecon. In 2016, he again joined the Chief Economist Team at DG Competition only to go back to Compass Lexecon as a Vice President in 2020. In 2021 he founded his own economic firm CompetitionSphere where he published a study with financial support from Meta on the economic benefits of surveillance ads SidenoteThis sentence was corrected on 1/2/23.

There is no suggestion that these persons have not followed the rules; the problem that CEO and LobbyControl assert is that the rules do not prevent such swift moves from private to public sector or vice versa.

Every single high-ranking official including the Chief Economist and the two Heads of Units have previously worked as economic consultants with Charles River Associates.

It is also very worrying that the Economist Team at DG Competition has hired extensively from these economic firms. Based on public information, out of 29 economists working at the DG Competition Economist Team, almost half (13) have previously worked as economic consultants at private firms. No less than 9 DG Competition officials previously worked at Charles River Associates (CRAI). Incredibly, this includes every single high-ranking official including the Chief Economist and the two Heads of Units!

Pierre Regibeau worked as Vice President at CRAI until July 2019 when he became the Chief Economist at DG Competition. He had been linked as an academic associate to Charles River Associates since 1998. According to the website of CRAI, he advised the firm on “landmark cases” including Microsoft, Ryanair/Aer Lingus, Servier, Samsung, and Android.

The EU claims its ethics rules addresses the problem of revolving doors. But the way these rules are being implemented is widely criticised. In 99 percent of cases authorisation by the European Commission is granted even when the move to the private sector takes place shortly after leaving the Commission.

Potential conflicts of interest in Commission expert group

These economic consultancies's influence also creeps in via the Economic Advisory Group on Competition Policy, a Commission expert group which has been set up to “improve the economic reasoning in competition policy analysis”. It is made up of academics involved in competition economics, but many are either closely linked or directly involved in economic consultancies. Out of 16 members, six carry out work for economic consultancies including Oxera, Bates White Economic Consulting, E.CA Economics, CRAI, and Lear. Another member of the advisory body has several Big Tech clients including Qualcomm and CenturyLink.

According to the Terms of Reference of the expert group, an existing interest requires a conflict of interest assessment by the Commission. In case of a conflict the Commission can decide to exclude an application or to make the appointment subject to certain restrictions. It is unclear if the Commission has put such restrictions in place. Sidenote On 7/2/23 the European Commission responded to a FOI request that it didn't have any documents related to conflict of interest assessments as it did not consider any of interests declared to be compromising the ability of members to act independently

Lobbying by economic consultancies

Economic consultancies are not only in close contact with the EU institutions when they represent clients in merger cases or advise the Commission in expert groups. They also publish reports on behalf of corporate clients and organise key events on competition policy in the EU. When the debate about the Digital Markets Act (DMA) of the EU started, economic consultancies shaped the debate from the start with reports on behalf of Big Tech. They set out to challenge the EU’s aim to limit Big Tech’s abuse of monopoly power with the DMA.

Despite their growing presence and their role both in advocacy and representation of clients, there is no information on economic consultancies available in the EU Transparency Register.

Take for instance Oxera: the firm has published various reports on the DMA that suggest it could lead to 'over-enforcement' and 'undermining innovation'. One of these reports was commissioned by Amazon, the other one by the Computer and Communications Industry Association (CCIA), a Big Tech association heavily involved in the debates on the DMA. Studies by Oxera were also mentioned in a leaked document that revealed Google’s aggressive lobby strategy to weaken the DSA/DMA. When asked about the report, Google never replied to LobbyControl’s request. Oxera also directly lobbied the Commission by participating in the feedback procedure of the Digital Service Act (DSA). In its submission, the firm lobbied the Commission against prohibiting certain harmful practices such as self-preferencing (ie companies unfairly favouring their own products via their own platforms) and highlighted the “efficiencies and the value created by platfoms’ business models”.

Or look at Compass Lexecon. The consultancy published a report on the DMA, too, that was sponsored by Google and published in June 2021 at the height of the legislative process. It was written by several authors, among them Miguel de la Mano, former Head of Unit at DG Competition, already mentioned above.

Charles River Associates also got involved in the expert debates on the DMA. For instance, Philip Marsden, a senior advisor at CRAI and former regulator at the UK’s competition authority CMA was interviewed in one of the leading Brussels digital policy podcasts 'jammingdigital' on the DMA. CRAI also sponsors key competition policy events in Brussels, such as last year’s 'EU merger control' conference. Oliver Latham, Vice President of CRAI’s European Competition Practice, who worked on Uber’s merger with Grab and Careem spoke on the DMA at the conference. Like the other economic consultancies, RBB Economics also contributed to the debates around the DMA. Benoit Durand for instance, Partner at RBB Economics in Brussels, participated in a panel discussion in May 2021.

Bursting the Brussels bubble

Considering the many political activities economic consultancies are involved in, they should be seen for what they are: lobby groups that often represent large companies and therefore need to disclose their work. They should register to the EU’s Transparency Register, so their activities can at least come under more public scrutiny.

Meanwhile, DG Competition urgently needs to defend its capacity as an independent regulator by disclosing more information on the submissions they receive, not only from economic consultancies, but from everyone. That way, potential spamming becomes more easily identifiable, and can be criticised for a start.

Shortly after his mandate former Chief Economist Tommaso Valletti called for the Brussels bubble to be burst open.

Finally, the Commission needs to address the conflicts of interest that arise from the many revolving door cases between DG Competition on one side and economic consultancies on the other. Existing rules including cooling-off periods are rarely applied.

Big Tech has so far taken advantage of economic consultancies’ undercover lobbying and the secrecy in competition policy. Amazon, Meta and co profit from this secrecy. A first and fundamental step to fight Big Tech’s monopoly is to open up the antitrust-establishment to more public scrutiny. Or as former Chief Economist Tommaso Valletti stated in an interview after his mandate: “this Brussels bubble has to be burst open”.

Eighteen organisations have today written to the European Commission to make the economic submissions they receive public. Read the letter here.

Note: this text was updated on 1/2/23