Stay always informed

Interested in our articles? Get the latest information and analysis straight to your email. Sign up for our newsletter.

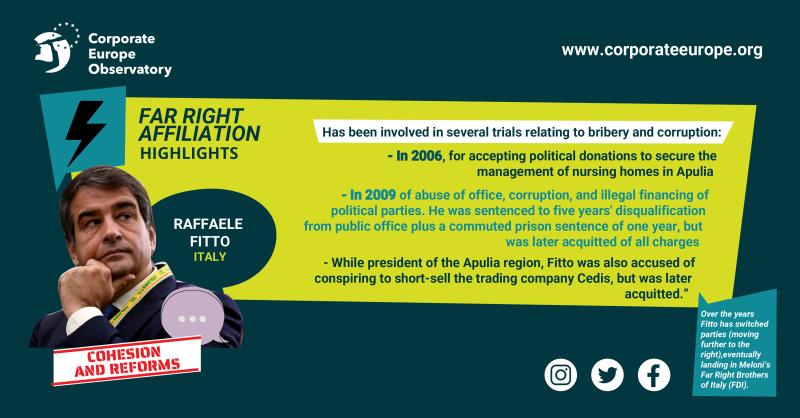

Raffaele Fitto, Brothers of Italy (FdI), part of ECR

Raffaele Fitto is Italy’s Minister for European affairs, in the Meloni government (Euractiv) since 2022. In this role, Fitto has been head of Italy’s National Recovery and Resilience Plan (NRRP) (Euractiv), ie in charge of handling the huge amount of money the country received through post-Covid recovery fund Next Generation EU, with mixed results: “Italy’s finance ministry calculated that less than €50 billion out of around €192 billion has been spent by the beginning of July [2024]. The Commission called for acceleration.” (Politico).

Domestically, over the years Fitto has switched parties (moving further to the right), and has been a Member of the Chamber of Deputies several times (2006-2014), and in 2008, was designated as Minister for Regional Policy. Fitto’s academic background is in law, and he has also served as Vice-President of the Apulia Region from 1995-1998 and President from 2000-2005 (source).

Fitto is also a long-standing former MEP: an EPP MEP from 1999-2000 and 2014-2015, then an ECR MEP 2015-2022, including holding the role of Vice-Chair and Co-President of the ECR (EP and EP). In 2022, when co-president of the ECR, Fitto said in an interview that the priorities of the ECR were “supporting economic recovery by putting European citizens and businesses, already struggling before the pandemic crisis, back to the centre of the EU’s agenda”, respecting the rights and sovereignty of Member States, “countering illegal migration, with renewed support to border states”, and building “sustainable economies in a realistic way” such that “environmental protection should not impose a greater burden on some countries than others” (Euractiv).

Fitto has been involved in several trials relating to bribery and corruption in Italy, including relating to the Italian health care system (2006 – re. accepting political donations to secure the management of nursing homes in Apulia); he was found guilty in 2009 of abuse of office, corruption, and illegal financing of political parties, sentenced to five years' disqualification from public office plus a commuted prison sentence of 1 year, but was later acquitted of all charges. While president of Apulia, Fitto was also accused of conspiring to short-sell the trading company Cedis, but was later acquitted (source – wikipedia).

Fitto “is widely seen as a pragmatist, an expert on handling EU funds and someone who could help the Italian PM reset her relationship with von der Leyen” (Politico).

Georgia Meloni, the far-right leader of the Brothers of Italy (FdI) – a party “rooted in a post-war movement that rose out of dictator Benito Mussolini's fascists”, has been Prime Minister since autumn 2022, part of a right-wing alliance that includes Matteo Salvini's far-right League and former PM Silvio Berlusconi's centre-right Forza Italia (BBC). During the election campaign Meloni made a speech saying “Yes to the natural family, no to the LGBT lobby, yes to sexual identity, no to gender ideology... no to Islamist violence, yes to secure borders, no to mass migration... no to big international finance... no to the bureaucrats of Brussels!" - though at the same time, Meloni “worked hard to soften her image, emphasising her support for Ukraine and diluting anti-EU rhetoric” (BBC).

In Meloni’s government’s first year in office she is considered to have attempted to “distance herself from the neo-fascist label”; to have had double standards on immigration and asylum (welcoming Ukrainians but not refugees from wars in Afghanistan, Syria, southern Africa); persecuted NGOs; and, told municipalities to stop registering non-biological parents in the birth certificates of children with two fathers or two mothers (Euronews). Meloni’s government also passed a law allowing pro-life groups to go into abortion clinics to try to persuade pregnant women not to abort and doctors not to perform the procedures, and placed loyalists in senior editorial positions at Rai, the state-owned broadcaster (source).

With respect to the EU, Meloni has softened her anti-Europeanism: “Italy needs Europe as much as Europe needs Italy. As a result, Meloni has had to find a way of working with the European institutions and vice versa, the European institutions have had to make an effort to work with her” (Euronews).

Meloni’s expected animosity towards Brussels didn’t really emerge (in part because Italy needed billions in post-Covid EU recovery funds), instead engaging positively and being “instrumental in securing a long-awaited deal on the reform of EU asylum rules” including travelling “with Von der Leyen on three occasions to north Africa, signing deals with Egypt and Tunisia to help slow migrant departures.” von der Leyen has said she’s “been working very well with Giorgia Meloni”, who is “clearly pro-European”; Meloni has also become known as “the Orbán whisperer” for helping to get Hungary on board. The shift to the (far)-right in the EP elections has led to her being described as a possible ‘kingmaker’ for the EU: “Courted by both the resurgent, if deeply divided, hard right and by the centre-right commission president Ursula von der Leyen, Meloni has emerged as a possible kingmaker who could end up swaying the EU’s direction on several key issues….If she can successfully build a bridge between Europe’s conservatives and at least part of its hard right, Meloni could effect quite a radical change in the EU’s direction – on issues as vital as climate change, enlargement and immigration.” However, while Meloni has been “a model of respectability on the EU stage”, she has been “pursuing her culture wars – against independent journalism, same-sex parents and LGBTQ+ rights – at home. As one EU diplomat put it, Meloni “may have shown herself to be a pragmatist, but she’s a conviction politician – and her politics are still hard right” (Guardian).