Bias baked in

How Big Tech sets its own AI standards

Setting ‘harmonised standards’ for artificial intelligence is a crucial element of the EU’s recent AI Act. But who develops these standards? Corporate Europe Observatory reveals how Europe’s standard-setting bodies dealing with AI are heavily skewed towards the tech industry. Behind closed doors, corporations are writing rules that will govern their own AI products – including on how to prevent fundamental rights violations of European citizens.

Oracle was “proud to be at the forefront of Artificial Intelligence (AI) standardization,” a company executive wrote recently on LinkedIn. The company would ensure standards are “ethical, trustworthy, and accessible to all”.

At first glance, this may make sense. Oracle is a multinational providing database software and AI tools. They have technical expertise to tap into.

But Oracle is also one of the world’s ten largest tech companies. It got its start as a CIA project and is heavily involved in using AI for global “mass surveillance”. The multinational sells its products from the US to China, and its founder, Larry Ellison, briefly overtook Jeff Bezos as the world’s second richest man this year.

Like Oracle, many of the world’s major tech corporations - Microsoft, Amazon, Huawei, IBM, and Google - are deeply involved in creating permissive, light-weight standards that risk hollowing out the EU’s AI Act. With little to no transparency, private standard-setting organisations are writing rules that have legal status in the EU. Independent experts and civil society are out-numbered, under-funded, and struggling in the face of the corporate dominance.

With little to no transparency, private standard-setting organisations are writing rules that have legal status in the EU.

Based on expert interviews with over ten people active in European AI standard-setting, social media analysis, and public documents, this investigation by Corporate Europe Observatory outlines how private standard-setting organisations – stuffed with experts from tech corporations – get to define what ‘trustworthy’ AI means. Behind closed doors, these industry-dominated forums write rules that will have legal status in the EU.

The tech industry presents standard setting as a purely technical matter, devoid of politics. But standard setting is highly political. Defining bias or fairness in AI systems is not simply a technical matter. While Big Tech firms are working hard to keep rules as weak as possible, Europe’s fundamental rights – ranging from labour rights, to protection against discrimination, to medical privacy to name just a few – are on the table. Independent experts and civil society have little to no say in the matter.

This is the reality of setting AI standards in Europe.

The AI Act adopted

The EU AI Act entered into law on 1 August 2024. As Corporate Europe Observatory previously documented, this process was heavily lobbied, with an outsize industry influence leading to a severely watered down text. While industry celebrated “significant improvements on the finish line,” digital rights organisations and trade unions were highly critical of the outcome.

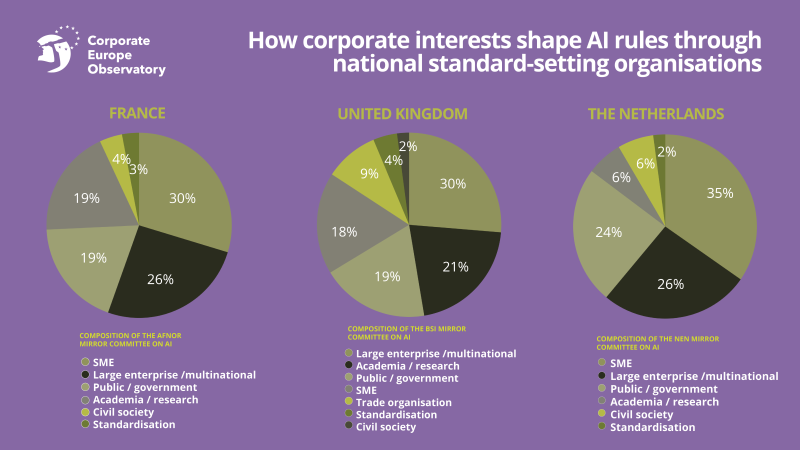

Figure 1: AI Act’s risk-based approach, from minimal to unacceptable risk.

Source: Ada Lovelace Institute

The AI Act provides rules for putting AI systems on the market across the EU. At the same time, it aims to protect EU citizens from harms caused by AI. The regulation takes a “risk-based approach”. The riskier the AI, the stricter the rules. Some applications, such as spam filters, would have little to no limitations. At the highest, “unacceptable” risk level, reserved for example for “social scoring” to measure the trustworthiness of people based on their online and offline behaviour or other personal data, would be banned completely.

Most of the AI Act focuses on systems deemed “high-risk”. These are systems – estimated to be 10-15 per cent of all AI – which are used in domains such as critical infrastructure, education, the workplace, the judicial system, or to process sensitive biometric data. AI could also be high-risk if it posed “a risk of harm to health and safety, or have an adverse impact on fundamental rights”.

AI’s social impacts and human rights risks

It is now widely recognised that as AI models are applied across society, they can recreate or amplify existing patterns of social prejudice, bias, and inequality. Flawed or biased training data may lead AI to discriminate against people based on race, class, gender, disability, sexuality, and age, or to create new, artificial boundaries to exclude people.

From credit scores to employee management, algorithms can trap people in poverty or enable intrusive worker surveillance. Social groups who are already vulnerable or discriminated against, such as migrants, refugees seeking protection, job seekers, or people seeking state support, have been shown to be most at risk from profiling or biometric mass surveillance.

This is not hypothetical. Across the world, for example in the Netherlands, the UK, and Australia, biased algorithms have falsely accused thousands of people of defrauding social security benefits.

According to the AI Act, high-risk systems would need to comply with several requirements, such as proper risk management, data governance, transparency, and accuracy. To prove they meet the requirements, providers of high-risk systems need to undertake a conformity assessment procedure.

For most systems, this is a “self-assessment” that the company can do in-house – an important win industry secured in previous rounds of lobbying. Providers must also conduct a fundamental rights impact assessment, to assess the AI’s trustworthiness and avoid rights violations.

But while the AI Act gives some guidance, these requirements are not yet operationalised in the legal text. Without specific guidelines from the AI Act, companies that want to put an AI system on the EU market do not actually know what, for example, “transparency” or “risk management” or “trustworthiness” mean in the eyes of the law.

Instead, legislators opted to leave these details to be defined by standard-setting organisations.

This is where “harmonised standards” come in. And the devil is in these technical details.

Standard-setting in the EU

Engineers have come together to create national and international products standards for over a century (see Box below). With the rise of neoliberalism, roughly since the 1980’s, it has increasingly become an official policy tool in the European Union.

Under the EU’s New Legislative Framework (NLF) for product safety regulation, issued in 1985, the European Commission can request European standards organisations to develop a “harmonised standard”.

A harmonised standard ensures a product complies with the essential safety requirements set out in an EU regulation. If providers that want to introduce a system on the EU market follow the harmonised standards, they then receive a CE mark and can safely assume to be compliant with EU law.

One study (funded by Apple, Huawei, and standard-setting organisations) observed a dual purpose to European harmonised standards – “to serve European industry” and “to assist EU policy”.

But serving industry does not mean European citizens are also well-served. In fact, when European policy is meant to protect the rights of citizens, it may be at odds with the need to serve industry. Researchers have pointed to the deficit in legitimacy in standardisation.

Natalia Giorgi of the European Trade Union Confederation (ETUC), who has long participated in European standard-setting, explained in an interview with Corporate Europe Observatory: “Standardisation is market-driven, profit-led, where industry develops technical specifications. In Europe it is also used to support internal market legislation. It is a public-private partnership, so that the law would set out the legal requirements products need to comply with in order to be placed in the internal market and the standards provide the technical requirements.”

Standardisation essentially pulls public decision-making into a largely private domain. Most standard-setting organisations are private non-profit organisations. Historically, they have been dominated by industry, and they often lack democratic and societal input. Their processes are frequently untransparent and generally outside means of democratic accountability. Some standard-setting organisations charge steep membership fees. Most sell the standards they produce rather than making them publicly available (although a recent EU court ruling may be changing this practice).

Standardisation pulls public decision-making into the private domain. Most standard-setting organisations are private non-profit organisations. Historically, they have been dominated by industry, and they often lack democratic and societal input.

Even though harmonised standards are produced by private organisations and do not originate from EU institutions, the European Court of Justice ruled they have legal status in the EU. This is because harmonised standards are prepared under an EU mandate and offer a presumption of conformity with the law.

In short, harmonised standards are the easiest way for a company to follow the law. When it comes to AI, most companies putting AI systems on the EU market will therefore follow these guidelines. This gives the standards great importance.

A brief history of standards

Standard setting initially consisted nearly exclusively of engineers who “invented a new process to create technically sound standards for industry,” write Yates and Murphy in Engineering Rules. This created “a timely way to set desirable standards that would have taken much longer to emerge from the market and that governments were rarely willing to set”. Yates and Murphy argue that without such standards, much of what consumers buy would be more difficult to produce. There would also be far more conflict between producers and customers.

There were three waves of standardisation. It started with national standardisation in the early twentieth century. This was followed by international standardisation during and after World War II, which saw the creation of the International Organisation for Standardization (ISO).

From the 1980s onward, the rise of the internet and the prominence of the neoliberal paradigm gave way to a more privatised standardisation in industry consortia. Increasingly, standardisation focused not just on the technical aspects of manufacturing, but on “a broader set of managerial and social issues” such as quality assurance, environmental management, and social responsibility. During this period the IEFT (Internet Engineering Task Force) became a prominent body for internet standards.

Standard-setting at the European level broadly followed these global trends. National organisations, such as DIN in Germany, AFNOR in France, and BSI in the UK, were created in the early twentieth century. The post-war period saw the creation of CEN and CENELEC, two European standardisation organisations that brought together the national bodies to create “European standards”. In the 1980s, they were joined by ETSI, the European Telecommunications Standards Institute, focusing specifically on ICT standards.

Standardising fundamental rights

In a May 2023 request, the Commission asked CEN and CENELEC to focus on setting standards for “ten concrete aspects of AI”. The standards would cover issues such as risk management, transparency, human oversight, cyber security, quality management, and the conformity assessment procedure.

CEN and CENELEC set up a Joint Technical Committee – JTC21 – with five working groups. In the autumn of 2024 the committee’s chair, Sebastian Hallensleben, published a complicated “dashboard” that showed several dozen work items, covering a range of work from AI terminology to risk management, trustworthiness, and “managing bias in AI systems.”

“It is highly unusual for a standardisation committee to publish this kind of intermediate information but the intense interest from industry, society and policymakers warrants extra transparency,” wrote Sebastian Hallensleben, the JTC21 Chair.

Transparency is indeed warranted. As the academics Mélanie Gornet and Winston Maxwell of the Institut Polytechnique de Paris observed, the AI Act is the first time harmonised standards are used to attest compliance with fundamental rights.

The AI Act is the first time harmonised standards are used to attest compliance with fundamental rights.

Previously, standard setting was limited to product safety, setting out technical specifications for, say, medical devices. Or children’s toys – their durability, their flammability, or what chemicals are restricted.

“So far, it’s been limited to product safety and in particular to support health and safety requirements,” Natalia Giorgi of the ETUC told Corporate Europe Observatory. “For the AI Act, it is the first time this is done to make sure it does not impact fundamental rights. But how can you technically translate human rights into standards?”

Researchers and civil society organisations have voiced concerns over the decision to use technical standards for complex societal questions. The academic Charlotte Högberg has called this technological solutionism which allows “for the standardization of social values (or even human rights) to be carried out in the same manner as any other technical product or procedure”.

As the Ada Lovelace Institute has pointed out, requirements under the AI Act are often worded ambiguously. For instance, according to Article 9, the risk of a high-risk AI system to fundamental rights, health and safety must be “acceptable” following a risk mitigation process.

But what is an “acceptable level” of risk ? How much bias can a system have? What is the “threshold” at which data is representative enough?

These are complex normative issues of fundamental rights, which are generally left to legislators or, in the case of violations, judges. But with the AI Act, the EU has opted for a business-friendly approach where these complex societal questions are put in the hands of standard-setting organisations.

Moreover, standard-setting organisations tend to focus more on a process than a specific outcome. “This can be unsatisfactory in that it tends to make enforcement of an outcome harder,” said JTC21 Chair Sebastian Hallensleben.

In other words, an AI system might have a CE mark, which companies get by following the processes defined in the harmonised standards, but that won’t garantuee the AI system won’t be biased or discriminatory.

Kris Shrishak, an Enforce Senior Fellow at the Irish Council for Civil Liberties (ICCL) who for a long time participated in standard-setting, explained.

“You want to have representative datasets, and if this is standardised at the technical level, this means you may have to do X number of steps to detect, and then to address, the bias in the data.” Shrishak said. “But [a company] can tick all the boxes and have a standardised system, which is compliant with the law, and then the harm may still be there.”

These questions are of paramount importance. By choosing to rely on harmonised standards, those setting the standards are taking decisions that may impact the fundamental rights of all European citizens.

“You’re putting that in the hands of private stakeholders, who have a financial interest in standardisation?” asked ETUC’s Natalia Giorgi.

In a written response the EU Commission said that the integration of fundamental rights into product safety regulation such as the AI Act might appear as a new challenge, but that the "standardisation request to CEN and CENELEC contains strong references to the inclusivity of the process and the need to gather expertise in fundamental rights".

Lack of transparency

When the Commission asked CEN-CENELEC to develop the standards for the AI Act, it left another European standardisation organisation, ETSI, out of the process. Reportedly the EU considered that US and Chinese companies had gained the upper hand there.

But do CEN and CENELEC fare better?

There is little official information on who is involved in AI standards at CEN and CENELEC. The bodies do not publish lists of the standard-setting participants, and the secretariat responsible for the JTC21 committee did not respond to Corporate Europe Observatory’s request for a list of participants.

On top of that, there are strict secrecy rules. CEN-CENELEC’s Code of Conduct states that participants in meetings are committed to “Revealing neither the identity nor the affiliation of other participants.”

A source in a non-profit involved in the standardisation process, who requested not to be named to speak freely, said “the confidentiality rules are so broad, I cannot even discuss who is on the committee.”

Despite the confidentiality, many of the participants in the JTC21 – the joint CEN and CENELEC committee tasked with developing the standards for the EU’s AI Act – openly advertise and discuss their work online, in particular on their LinkedIn accounts. They often link to each other in status updates on the JTC21 and tag other participants.

By the numbers: corporate rulemaking

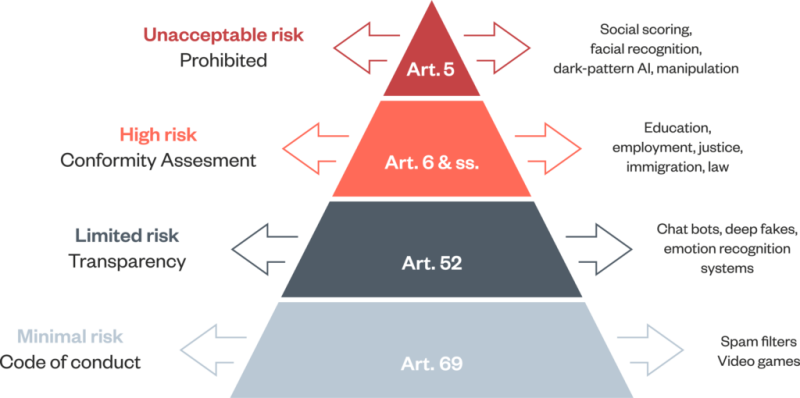

Through online analysis Corporate Europe Observatory found 143 people who claim to be involved in the JTC21 committee.

54 of the identified JTC21 members represent corporations and 24 represent consultancies. Together, these 78 individuals make up more than half (55 per cent) of the identified JTC21 members. (To see the methodology for gathering this data see the end of the article.)

Figure 2 – JTC21 members by sector, identified by Corporate Europe Observatory.

More than half the corporate representatives are European. Some larger European companies, such as Philips and DEKRA have two identified representatives. For most European industry players – ranging from widely different sectors such as telecoms, medical devices, or cybersecurity – only one representative was found.

Nearly a quarter of the corporate representatives are from US corporations, and they come in greater numbers from a select group of multinationals that can send multiple representatives to JTC21.

Corporate Europe Observatory identified four current (and one recent) Microsoft employees on the committee. There are also four current (and six former, long-time) IBM representatives, alongside two Amazon representatives, and at least one current (and two recent) Google employees on the JTC21. Intel, Oracle, and Qualcomm send representatives too.

At least two JTC21 experts are also working for DIGITALEUROPE, a tech lobby group in Brussels.

The Chinese participation we found was small, but notably all four representatives of a Chinese corporation represented Huawei. They worked in JTC21 alongside two recent Huawei employees, now at other organisations.

In a written response the Commission "acknowledge[s] that the industry still represents the majority of participants", but that "this is also a functional feature of standards which are highly technical and should take into account inputs from industry". Furthermore, the Commission responded to our questions that "even if improvements are still possible [...] the number of experts from societal organisations and civil society [...] are clearly more numerous than for other safety regulations."

Despite these expressed efforts, inside sources told Corporate Europe Observatory, Big Tech dominates the standard-setting process.

"Global players have an interest in European standards that are as close to international standards as possible,” said Sebastian Hallensleben, the JTC21 chair. “Many stakeholders prefer standards that focus on best practice rather than enforceable requirements.”

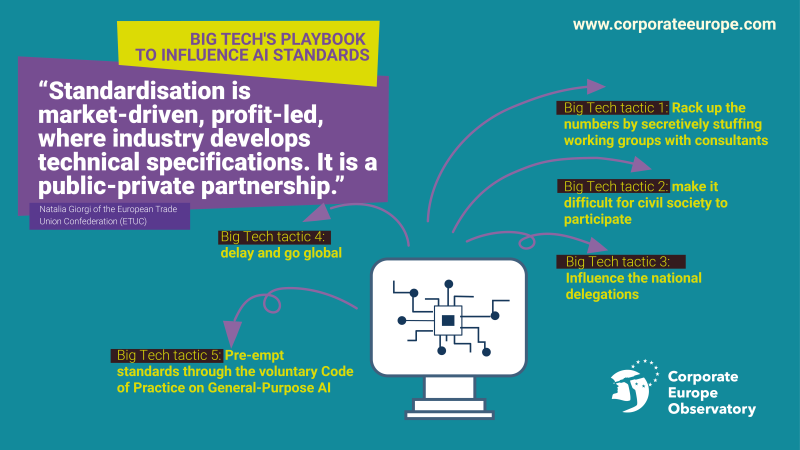

Below we outline the tactics these global players use to pursue their interest of light-weight standards.

Figure 3 - Industry tactics to shape AI standards

Big Tech tactic 1: rack up the numbers

There are several inherent advantages for multinationals in the standardisation process. They have greater resources, plus decades of experience. They have branches in multiple European countries, through which they are able to take part in several national delegations and get more of their experts on the JTC21.

“If a company has branches in the EU, it can join the national standardisation bodies of all the countries where it has branches.” said Camille Dornier who, until recently, worked for BEUC – the European Consumer Organisation and followed the JTC21 work. “It is a business-oriented model. You need to pay membership fees to the national standardisation body, and then you can ask to be part of the national delegation.”

The corporate dominance allows Big Tech to push for standards that are light-weight and hard to enforce.

Consultants may serve to further obscure whose interests are represented. The multinational consultancies Deloitte and Ernst & Young, for example, each have multiple representatives to the CEN-CENELEC committee. It is unclear who their clients are and thus whose interests are represented.

I have seen people from seven different countries raising their hands at the same time and voicing very similar opinions, so you think there’s consensus. In fact, you realise they all have the same line manager.

Anonymous expert involved in AI standardisation

Sources suggested that large corporations pay consultants to have a voice in the national bodies where they don’t have an office – to “stuff it with allies,” as one expert said. During a JTC21 meeting, only the name of the person and the country will be mentioned. Consultants do not have to declare publicly the interest they are paid to represent.

“I have seen people from seven different countries raising their hands at the same time and voicing very similar opinions, so you think there’s consensus,” one expert with long experience in AI standardisation, who requested anonymity to speak freely, told Corporate Europe Observatory. “In fact, you realise they all have the same line manager.”

Others confirmed this. “We have seen situations where you have an expert of company A, defending a comment of an expert of a different country, but also company A,” recalled Camille Dornier.

Those who can muster up the numbers, are more likely to be able to influence the consensus in the working groups. “All these companies have internal policies, and the closer you get [the standard] to that, the easier to comply,” said Shrishak of the ICCL. “You will provide your internal policy as an input that goes into drafting. It often starts with an empty page, an open call for contributions. Those who already have a policy can set the frame.”

At the working-group level, where members represent not their national delegations but only themselves and their companies, that could lead to situations where Big Tech is close to being the only voice represented.

“One reason to do standards in Europe and not at ISO level is to have only Europeans in the room,” an expert active in JTC21 said, “but there were meetings where I have been the only European in the room, period. Or the only European representing a European interest.”

Big Tech tactic 2: make it cumbersome

Participating with multiple representatives, or employing boutique consultancies, is not something that small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) are able to do. Independent experts or civil society organisations struggle too. In Corporate Europe Observatory’s sample, only 23 representatives (16 per cent) came from academia and think tanks, and 13 from civil society (9 per cent).

Historically, standard-setting organisations saw little to no need for the participation of civil society. They saw themselves as solving engineering problems, not political questions. But as standardisation took on new processes, such as environmental standards or corporate social responsibility, it became clearer this could not be left to corporations alone.

Large corporations typically have a resource advantage over non-profit stakeholders, even when the latter mobilise everything they can.

Sebastian Hallensleben, chair of JTC21

The EU has previously recognised and tried to remedy the lack of representation of societal interests in the discussions. In Regulation 1025/2012, it defined four categories of social interests – SMEs, consumers, environmental, and workers – and ensured the right of their representation in the process of standard-setting.

Four organisations – one for each issue – were accredited (in typical EU jargon) as “Annex III” organisations and would receive EU funding to participate. Nevertheless, they would not have voting rights.

The ETUC, the federation of European trade unions, is one of those “Annex III” organisations. It is singularly tasked with representing trade union interests in the European standard-setting bodies. Natalia Giorgi of ETUC said “It is a full-time job to consolidate all feedback while actively participating in meetings.”

But the funding is often insufficient, and pales in comparison to the resources large tech firms have. Experts typically cover their own costs, such as travel and hotel, for participation in meetings.

“Large corporations typically have a resource advantage over non-profit stakeholders, even when the latter mobilise everything they can,” said JTC21 chair Sebastian Hallensleben.

Small players face logistical challenges too. “It took nine months to even get access to documents,” said the non-profit expert quoted above, “but some of these people have been working on standardisation for twenty years. They know the code by heart.”

“Multinationals have experienced experts, who know the process well,” Camille Dornier of BEUC said. “You need technical knowledge and expertise of the standardisation process.”

Nevertheless, the few civil society actors and independent experts present are very active in the working-group debates. They told Corporate Europe Observatory they are making a positive difference in ensuring proper protections against fundamental rights violations. Through active participation they may be able to influence the consensus at working-group level.

But the structural set-up of standard-setting does not favour civil society. Strategic decisions and votes on the draft standards are taken by the representatives of national standard-setting organisations, which are often filled with industry representatives (discussed below).

“In AI standardisation, there is more participation, said BEUC’s Camille Dornier. “But will it have an impact? We will see once the voting has passed.”

Big Tech tactic 3: influence the national delegations

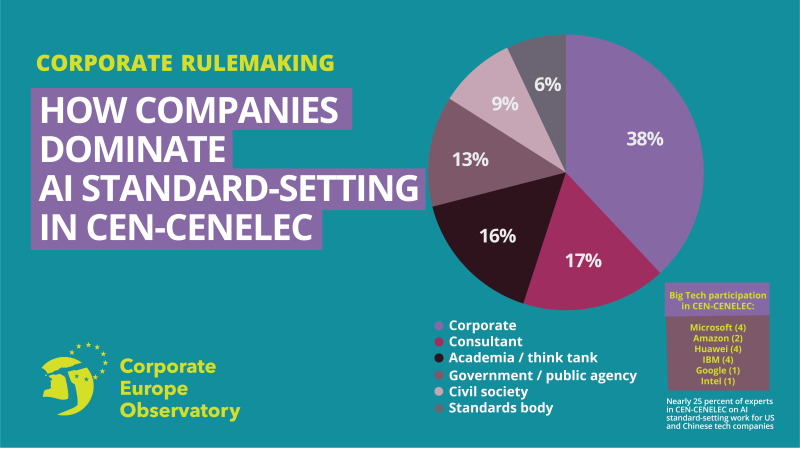

In contrast to the “Annex III” civil society organisations, national delegations do hold voting rights at the JTC21 strategic committee level. National standard-setting organisations confer with their national membership in a “mirror committee” and adopt a position to take at the European level. As such, having a voice in the national delegations carries weight.

And only a select group of large tech corporations – some European but mostly US – can participate in several national standard-setting bodies.

“If I am a small company in Germany, I may send my member to DIN. If I am Google, I am sending people in multiple countries,” said Kris Shrishak of the ICCL.

“I would send my best people to Germany, France, and then echo everywhere,” continued Shrishak, “You don’t solve the problem at the table, but before it comes to the table.”

Insides sources who spoke with Corporate Europe Observatory confirmed this is common practice. A tech giant like Microsoft or Amazon may be able to put one employee in a national committee if they have an office in that country. Or they may send a consultant. For a multinational, the membership fee to the national body is not a significant barrier to entry.

Information from the few national bodies that publish who participates in their national “mirror” AI committee supports this. Analysis of the AI committee of France's AFNOR, one of the most influential national standardisation bodies, showed that industry makes up more than half the committee, and includes multiple participants from Microsoft, Amazon, Huawei, and IBM. By our count, only 4 per cent come from civil society and 18 per cent are academics and researchers.

The UK’s BSI, which despite Brexit partakes in European standardisation, shows similar numbers. Over half is made up of industry representatives, and a quarter are large corporations or multinationals, including all the usual suspects – Amazon, Google, Huawei, IBM, Microsoft, and Meta. One in five are academics, and just two of the 89 members come from civil society.

In the Netherlands, out of the 52 listed members on the national AI committee, more than half (30) are from industry. It includes more different branches of the Dutch multinational Philips than there are civil society organisations.

Moreover, insiders say the numbers show only a part of the picture. On paper, national AI committees may have dozens, or more than a hundred, participants. But few other than the Big Tech firms have the resources to participate actively.

“In practice there are twenty people who keep track of it,” an officer active in a national AI standardisation committee, who requested anonymity, told Corporate Europe Observatory. “And people who actually write the standards, it is maximum five.”

Microsoft certainly is among those few who participate actively. At least three national delegations are regularly headed by officers working for Microsoft.

One of these is the delegation of the NSAI, the Irish standard-setting body, headed by a Microsoft national standards officer. Together with Microsoft, the NSAI co-hosted a plenary meeting of the JTC21, in the Microsoft office in Dublin in February 2024. These plenary meetings bring together the national delegations for strategic sessions.

The Microsoft-hosted plenary took place as the AI Act was about to be adopted and standards were becoming the next hot topic. Microsoft could hardly have found a better time to display its soft power in the debate on AI standards.

Microsoft’s corporate sponsorship is moreover not an exception. The most recent JTC21 plenary meeting in Turin in November ‘24 was sponsored by Amazon which led to several critical comments on LinkedIn from civil society and academics.

Figure 5 - Microsoft co-hosting the JTC21 plenary in Dublin

Source: screenshot of Vimeo

Heads of delegation do not have individual decision-making authority and convey the positions at the JTC21 plenary that have been reached by consensus in the national bodies. For heads of delegation to divert from the position reached at national level would be a violation of the rules of standard-setting bodies.

The role of committee chair or head of delegation is influential however. Typically, people who take on this role have the time and resources to be active participants in the work of the committee. Because of their social position and role in the committee’s work, their opinion generally carries weight, even when they are just one voice debating what the national committee’s position should be.

“The real influence is in how you say things,” said a JTC21 expert who requested anonymity to speak freely. “You can abstain in a way that gets everyone else to object. Or you can support without your heart to it. You can ask clarification questions at the right moment.”

There are serious concerns whether national positions can be represented in good faith by individuals employed by Big Tech companies that have a strong interest in the direction AI standard-setting will take.

Big Tech tactic 4: go global

To fully appreciate the reach of industry into European harmonised standards, it is necessary to look to international standards as well.

A proportion of European standards are directly transposed from the International Organisation for Standardization (ISO) and the International Electrotechnical Commission (IEC).

A December 2023 report from CEN-CENELEC shows that 35 per cent of CEN’s standards were direct adoptions of ISO’s, and 81 per cent of CENELEC standards were adoptions of IEC’s.

“The Commission wants standards to be internationally compatible,” Kris Shrishak of the ICCL said, “But they are most useful for companies in multiple jurisdictions, not for SMEs.”

At the global level, large industry is even more dominant. A 2004 study on ISO standards found that industry was “clearly the largest stakeholder group”, and together with the consultants made up half the participants. Academics or researchers were less than one in ten, and NGOs made up 3 per cent.

More recent figures than 2004 on ISO-IEC are not available. Sources involved in both the JTC21 and ISO-IEC related that while JTC21 is more diverse, at the global level, it is nearly exclusively Big Tech.

The sparse information publicly available about ISO-IEC’s working group SC42 on AI supports the image of Big Tech dominance. The committee is chaired by the Vice President of Huawei’s R&D arm. Many of its working groups are convened by corporate representatives, including employees from Huawei, Fujitsu, and NVIDIA, and a consultant who worked for 17 years for Microsoft. Convenors have significant power, as they determine the working group consensus.

Figure 6 - composition of ISO/IEC JTC1/SC 42

Source: ISO/IEC

Agreements between CEN and ISO as well as between CENELEC and IEC stipulate that “appropriate priority is given to cooperation with ISO provided that international standards meet European legislative and market requirements”.

In other words, global standards are supposed to take precedent. This immediately created issues in the JTC21. At the ISO-IEC level, standards can be requirements, which would need to be followed by all AI systems, or recommendations and statements of principle, which are much weaker.

“Requirements cost industry a lot of money,” an expert active at the SC42 and the JTC21, who requested anonymity, told Corporate Europe Observatory. The expert explained that due to tech lobbying ISO-IEC standards often remained only recommendations.

But at JTC21, only requirements help give the “presumption of conformity” with the AI Act that producers get if they follow the harmonised standards.

“By that very nature, the ISO-IEC standards contain too few requirements for Europe's purposes,” the same expert said.

There were at least two occasions when this came to a head in the JTC21. The first was over the adoption of ISO-IEC standard 42001, which deals with AI quality management.

“There was a big push from the US, from Big Tech, to use ISO-IEC 42001 to be that quality management system,” the SC42 and JTC21 expert said.

The 42001 standard had been edited in SC42 by Microsoft’s Marta Janczarski, who also serves as the JTC21 editor on this item.

But experts found the standard to be insufficiently aligned with European requirements. “42001 refers to an organisation and its processes, whereas the AI Act refers to products. These do not fit together very well,” JTC21 chair Sebastian Hallensleben told Corporate Europe Observatory. The focus on organisational processes is typical in standards, but as explained above, may not satisfy the AI Act’s intention to mitigate risk or prevent harm.

“The agreement in the end was that we would start the project and go line by line,” the expert active in the SC42 and JTC21 expert said. “Where we could align with international standards we would, and where we needed to diverge, we would… it was clear a generic management system designed before the AI Act was never going to work.”

The battle over the use of 42001 caused over a year of delay getting the work on quality management started. With a short timeline for the delivery of the standards, which the Commission wants done in 2025, this may end up causing further delays – and more uncertainty for smaller companies, which will be looking to the standards to comply with the AI Act.

Some interviewees suggested such delays in JTC21 may be intentional on the part of Big Tech, which prefers to keep the process at the global level. “There is a big push to do things at ISO,” the non-profit expert involved in the standardisation process told Corporate Europe Observatory. “In the best-case scenario, standards are improved at CEN-CENELEC.”

Another headache for JTC21 resulted from the use of ISO-IEC’s definition of risk, which ISO-IEC standards are expected to use. It would have allowed corporations to “balance off profit against human rights in a way that would be inappropriate,” the SC42 and JTC21 expert said.

The Commission confirms in a written response to Corporate Europe Observatory that some international standards are not in line with the AI Act: "This notably concerns ISO/IEC 42001:2023, which does not align with the AI Act, for instance on the notion of risk, which is understood by ISO as organisational risk, and not risk to health, safety and fundamental rights, such as in the AI Act."

Had the definition been used in European standards, firms could have balanced the measures to reduce risks to people’s rights caused by AI systems against risks to “opportunity and profit”.

“Nobody challenged this in ISO-IEC at SC42 until we saw this in a regulatory frame in JTC21,” the SC42 and JTC21 expert said, “so there’s this whole history of AI standards that use an inappropriate definition of risk.”

By holding the pen at ISO-IEC, tech multinationals were able to set the frame for the EU’s harmonised standards. The JTC21 experts did not, in fact, start with a blank page.

Debates over what elements of ISO-IEC standards to use by JTC21 are ongoing. The progress “dashboard” CEN-CENELEC published showed that more than a third of the standards under development in JTC21 had a high or very high degree of similarity to ISO-IEC standards.

For the seven ISO-IEC standards for which an editor was listed, six were corporate representatives; two were edited by Microsoft, one by IBM. In short, that meant that by holding the pen at ISO-IEC, these US multinationals were able to set the frame for the EU’s harmonised standards. The JTC21 experts did not, in fact, start with a blank page.

It is also a small world, and difficult to access if you’re not in the club. Many corporate experts are active at both the European and international level. Several of the interviewees told Corporate Europe Observatory that experts would say at JTC21 that they were set to discuss a file in SC42. Those unable to attend at ISO-IEC, like many of the civil society organisations accredited to the JTC21, would be left out of the discussion.

“It is great for companies, but not for civil society,” Camille Dornier of BEUC said. “Annex III organisations [the four stakeholder representatives accredited to CEN-CENELEC] are not automatically allowed at ISO-IEC. And even if they were, it would require that you double your resources.”

To what extent the international standards will be adopted by JTC21 remains unclear. In 2023 the Commission’s Joint Research Centre (JRC) concluded that “there are important elements where international work is not fully aligned with the requirements of the AI Act”.

The final word remains with the Commission, which approves the standards once CEN-CENELEC has developed them. For previous standards, it used the Ernst & Young (EY) consultancy to assess draft standards.

In response to questions from Corporate Europe Observatory about a potential conflict of interest – EY works for several industry players and is involved in the JTC21 itself – the Commission confirmed EY would not be involved in assessing the AI standards.

What the process will be for the Commission to approve the standards remains unclear. Corporate Europe Observatory contacted the European Commission officer responsible for the process, but received no response.

Big Tech tactic 5: the Code of Practice

During the negotiations over the AI Act, general purpose AI was the major focus of Big Tech’s lobbying. These are the models, including large language models and generative AI models such as ChatGPT, that are among the major AI systems produced by Big Tech firms. These general purpose AI systems are used or incorporated into a variety of uses by other companies; and their producers, generally Silicon Valley giants, wanted the regulations not to apply to the originator of the tech, but only to the companies deploying them in various ways.

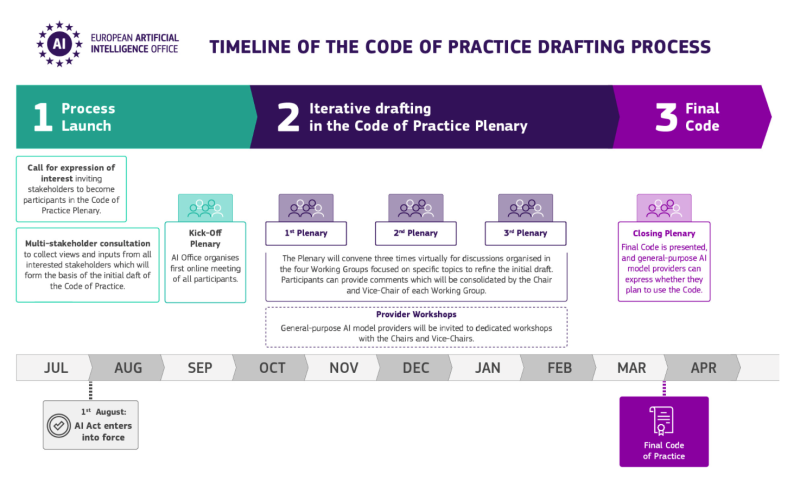

Instead of relying on standards to regulate general purpose AI, the Act set out that rules for these large AI models would be done through a “Code of Practice”. Drafting the Code of Practice is done in an equally, if not more, industry-friendly environment as the standard-setting process.

The EU’s AI office has invited providers of general-purpose AI models, as well as national competent authorities, to participate in drafting this code. Other stakeholders would have only a supporting capacity.

“It is a stop-gap solution. It is ‘standards-light’,” the non-profit expert involved in the standardisation process told Corporate Europe Observatory. “It is voluntary, company-driven, and will flesh out what criteria constitute systemic risk and high-impact capabilities, for example.”

The Code of Practice will also set out rules for copyright, publishing what training data was used on the AI, and how to report incidents.

Since the announcement, there has been a pushback from civil society. The Commission reported receiving 430 submissions for input on the Code of Practice, and almost 1,000 organisations and individuals expressed interest in the process.

The EU also published a list of the chairs for the development of the Code of Practice, which include “one of the godfathers of AI” Yoshua Bengio, former MEP Marietje Schaake, and various academics.

Figure 7 - Code of Practice timeline

Source: European Commission

But the bulk of the work (see figure above) will be done by general purpose AI model providers – mostly US Big Tech corporations. They will flesh out the content of the Code of Practice in “dedicated workshops with the Chairs and Vice-Chairs”. Other stakeholders are not present there.

A first draft of the Code of Practice was released in late November 2024. Working group chairs Yoshua Bengio and Nuria Oliver argued that it provides a “unique opportunity for the EU” and that “GPAI [general purpose AI] model providers, which are predominantly non-European, will also have to comply with some basic rules, and mitigate risks they are uniquely placed to address”.

The expected final result will be a checklist that corporations can use to demonstrate their compliance with the AI Act. But the “basic rules” will not be binding.

“No model will be forced to comply,” the non-profit expert continued. “But it will come before the harmonised standards – and set the tone for rules for general-purpose AI.”

A military connection?

Corporate Europe Observatory’s investigation shows that, although military AI is excluded, several JTC21 experts had defence connections. They worked, presently or previously, on AI for NATO, national militaries, intelligence services, or various security contractors.

This does not mean there is an active defence lobby. “I cannot recall a single instance where a military (or defence industry) agenda has been apparent in any way,” said JTC21 Chair Sebastian Hallensleben. Others said any sectoral lobbies other than Big Tech are negligible.

But there may be a transfer of ideas in the opposite direction. Patrick Bezombes, the JTC21 vice chair, who previously lectured on AI for the French army, explained: “Since the military has neither the skills nor the resources to develop and maintain complex AI standards, they will have to rely on civilian standards, which in most cases in Europe will come from JTC21.”

That the standards under debate may also find military application, even if only in non-weapons use cases such as logistics, seems to be one more argument for increased transparency of the process, especially given that fundamental rights questions are dealt with.

Conclusion

To many engineers, standard-setting organisations are where technical engineering questions are solved; a place where politics, government, and civil society should not interfere.

But standards are policy instruments, neither objective nor neutral, especially when they regulate fundamental rights. It is hard, if not impossible, to separate the technical questions from the fundamental rights questions.

From the national to the European and international level, standard setting organisations are dominated by corporate actors. Their workings are untransparent and lack democratic accountability, but the rules they make have legal status. Barriers to involvement of civil society remain high.

“If the law would need to establish all the technical details, the regulations would be even more complex. To establish these technical details, it has some advantage,” Natalia Giorgi of ETUC said. “But you can’t give [decisions about] fundamental rights to private organisations.”

The problem, of course, is that is largely what has happened as a result of the decision to rely on harmonised standards to implement the EU’s AI Act.

Some remain cautiously optimistic. “Standards should benefit rights,” Natalia Giorgi said. “If an AI takes a decision and there seems to be a discriminatory treatment. What are the requirements for how a system needs to avoid it? Who gets the data? Is there a report? Who reads the report?”

But the fight for trustworthy AI remains challenging. According to Kris Shriskak, the most important battle was already lost.

“Industry have convinced legislators it is a technical problem,” Shrishak said. “They have been really successful in turning a social issue into a technical one.”

Annex: Methodology

To identify JTC21 members Corporate Europe Observatory conducted searches for variations of the term “JTC21” on LinkedIn, which identified most people in our sample. Individuals who did not have JTC21 on their own profile (or did not have a profile at all) but were clearly described in LinkedIn posts by others as being involved were included too. This was supplemented by other online source material about JTC21 and its members – for example online profiles shared for talks or conferences – through which a small number of additional individuals were identified.

It is clear this is not a full membership list of the JTC21 committee. In response to questions from Corporate Europe Observatory the Commission quotes a number of more than 200 experts involved, but that at the moment no official statistics are available. As such, in the absence of publicly available information, our analysis relies on self-reporting. Several sources said the list compiled by Corporate Europe Observatory seemed accurate, but we were unable to confirm the membership in JTC21 for every individual who claimed it online. Furthermore, some JTC21 members do not list their membership online. The real numbers will therefore differ, but there is no reason to assume a bias in the self-reporting between individuals.