The Carbon Coup

How corporate capture is locking Europe into a fossil-fuelled future

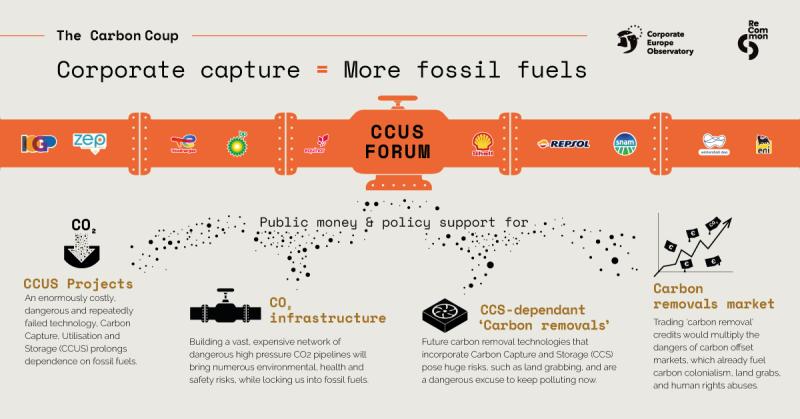

Despite three decades of failed projects and hundreds of millions of euros in public funding thrown down the drain, the EU has spent the past two years turbocharging policies to support Carbon Capture, Utilisation and Storage (CCUS). This technology aims to capture CO2 from polluting activities like the burning of fossil fuels, and then store it in products or pump it deep underground (in the hope that it will stay there). In February 2024, the European Commission presented its Industrial Carbon Management Strategy (ICMS), which proposes an array of measures designed to massively scale up CCUS and related CO2 transport infrastructure.

The EU had already proposed a target of capturing 50 million tonnes (Mt) of CO2 by 2030, and the ICMS ups this dramatically to 280 Mt by 2040 and 450 Mt by 2050. For the sake of comparison, EU countries currently capture just 1 Mt of CO2 per year. That means CO2 capture capacity would need to increase 450 times over the next 25 years.

Globally, CCUS has miniscule impact, in 2022 sequestering just 0.1% of energy-related CO2 emissions (much of which was used to extract more oil, thereby adding yet more emissions). The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change anticipates only a modest growth of 2.4% emissions sequestration by CCS by 2030 (even if implemented at its full planned potential), whereas renewables, efficiency, electrification, and the reduction of fugitive methane emissions can tackle more than 80% of global decarbonisation needs by 2030.

CO2 transport infrastructure is fraught with dangers. CO2 pipelines can leak or rupture – potentially explosively – while the release of compressed CO2 can result in the asphyxiation of humans and animals. In April 2024, for example, an ExxonMobil-owned CO2 pipeline leaked in the US state of Louisiana, resulting in the issuance of a shelter-in-place order for local residents to avoid the risk of asphyxiation. This followed a similar pipeline rupture in Mississippi, which necessitated evacuations and medical treatments. Nonetheless, the Commission envisages a total of 19,000 kilometres of this type of infrastructure by 2040 (costing €16 billion). Meanwhile, underground storage comes with the risks of potential leakage, contamination of drinking water, and stimulation of seismic activity.

So why is the EU ignoring the urgency of phasing out fossil fuels and instead planning to vastly scale up this risky, costly, almost non-existent and repeatedly failed technology at a speed and magnitude that has no basis in reality? Why the focus on carbon capture when better alternatives exist? Who will benefit from this resurgence, and who will lose out? Who is setting the agenda? These are the questions examined in our new report ‘The Carbon Coup: How corporate capture is locking Europe into a fossil-fuelled future’.

Key findings

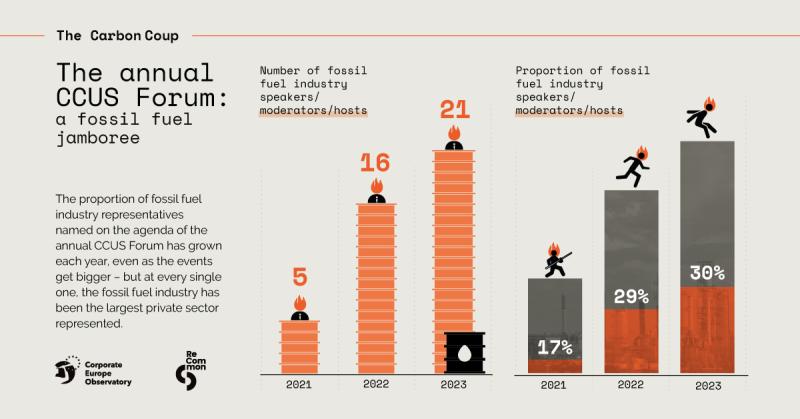

1) Fossil fuel interests dominate the CCUS Forum

- The oil and gas industry is a major actor behind these developments. The need for decarbonisation poses an existential threat to them, and they have created multiple ‘escape hatches’ to continue fossil fuel burning, including techno-fixes like CCUS.

- Fossil fuel industry-dominated groups are increasingly being given an official role in shaping EU climate and energy policy. The CCUS Forum, set up in 2021 by the European Commission, has been invited to steer regulation and public funding for CCUS, associated CO2 infrastructure, and speculative carbon capture and storage (CCS)-based ‘carbon removal’ technologies.

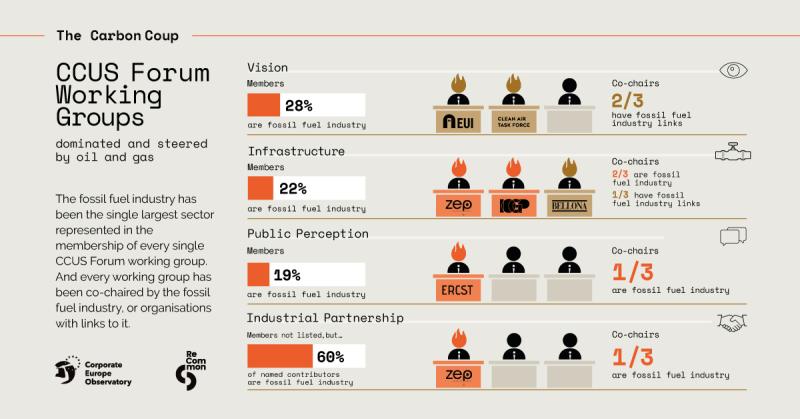

- The CCUS Forum is a not a group, but an annual event that sets up working groups, which in turn make proposals every year. Our report finds that the CCUS Forum becomes bigger and more dominated by fossil fuel interests each year – from companies like Equinor, TotalEnergies, Shell and Snam, to lobby groups like the International Association of Oil & Gas Producers (IOGP) and Zero Emissions Platform (ZEP). To date, every working group of the CCUS Forum has been co-chaired by the fossil fuel industry or organisations with links to it, and the largest sector represented in these working groups has consistently been the fossil fuel industry. Meanwhile, the role of NGOs and academia is comparatively tiny (while the role of groups critical of CCUS is practically non-existent).

- Our report shows how the Commission’s efforts to present the CCUS Forum as a ‘balanced’ multi-stakeholder group are misleading. This is doubly true in light of the ‘neutral’-sounding organisations active in the CCUS Forum that, on closer inspection, have links to or a history with the fossil fuel industry: pro-CCS NGOs Bellona and the Clean Air Task Force (CATF) for example, or the Florence School of Regulation. The latter has a wide array of fossil fuel funders, and two of its ‘part-time professors’ – Andris Piebalgs, and Christopher Jones, who presented a pro-CCUS paper at the first Forum – were formerly high-level officials in the Commission’s DG Energy. Jones subsequently moved to Baker McKenzie, a law firm whose current clients include oil and gas lobby IOGP, to work on topics including oil, gas and hydrogen. Notably, ‘blue’ hydrogen made from fossil gas with CCS is an oft-cited justification for CCUS infrastructure build-out.

- Our investigations also show that current and former MEPs involved in the annual forums are closely tied to the fossil fuel industry, or have held frequent meetings with oil and gas lobbyists. This includes the former rapporteur on the 2009 CCS Directive, Christopher Davies, who played an instrumental role in securing public funding for CCS, hand in glove with fossil fuel companies. Although billed only as a former MEP at the first two CCUS Forums, Davies was working for Rud Pedersen Public Affairs, a lobby firm whose clients at the time of the Forums ranged from IOGP to BP and Liquid Gas Europe. By the third Forum, Davies was billed in his new position as CEO of lobby group CCS Europe (whose members include e.g. gas transmission system operator Open Grid Europe) – the first time his fossil fuel connections were explicitly acknowledged. Recruiting former EU political heavyweights can, no doubt, be an important avenue of influence for the fossil-fuel industry and connected groups.

2) The EU Commission’s ICMS draws heavily on CCUS Forum recommendations

- Energy Commissioner Kadri Simson told the 2023 CCUS Forum, “you called for a specific and verifiable target for storage capacity, industrial support, and structural solutions… And this proposal does exactly that... And I do believe that this is an opportunity for EU oil and gas producers.”

- Numerous proposals and entire sections of wording in the Commission’s ICMS proposal closely resemble the recommendations in the papers published by the CCUS Forum’s working groups. The proposal mentions the CCUS Forum by name ten times. It follows the template drawn up by the ‘vision’ working group (co-chaired by the Florence School of Regulation and CATF), and explicitly gives the CCUS Forum an even bigger role in shaping EU CCUS policy and funding in the future, including more say in planning CCUS and CO2 infrastructure build-out. This ignores important lessons learned from other experiences, such as vested interests being allowed to plan for overinflated infrastructure needs in the gas sector. The ‘vision’ working group’s template, furthermore, is based on the false premise that without large-scale CCUS – and CCS-based carbon removals – the EU cannot meet its climate targets.

- The ICMS also takes on board a huge number of demands from the CCUS Forum’s ‘infrastructure’ working group (co-chaired by IOGP, ZEP and Bellona). These include ways to collectivise risks while privatising profits, such as minimising costs for polluters when building CO2 networks, funnelling EU and national public funds towards CO2 pipelines and storage sites (despite the European Court of Auditors’ conclusion that previous such transfers were a waste of public money), and planning provisions to protect fossil fuel companies from costs, risks or liabilities if things go wrong (or if the promised CO2 market fails to emerge).

- The ICMS proposal promises to “use the CCUS Forum” to “increase public understanding”– yet the Forum’s working group on ‘public perception’ touts the message that “it is crucial to establish the legitimacy of CCUS technology among the public”. This suggests that its aim is rather to manipulate public perception and fabricate consent for a dangerous and flawed techno-fix.

- The co-chair of this working group is the influential carbon market zealot Andrei Marcu, whose fossil-fuelled think tank is pushing for the EU Emissions Trading System to be expanded into a carbon removals market (an ill-advised idea that the ICMS has promised to consider). This scheme would allow polluters to continue to emit CO2, providing they purchase removal credits from ‘offset’ projects, such as those that involve CCS-dependent carbon removal technologies.

- The Commission also has open ears for the Forum’s demands for a CCUS Industrial Partnership, which would further formalise the role of fossil fuel and other polluting industries in shaping future CCUS projects, funding and regulations. Meanwhile, the CCUS Forum played a strategic role in convincing a number of Member States to board the CCUS train in 2023 via their signing of the Aalborg Declaration, which calls for a European CO2 network and market.

Our report concludes that the CCUS Forum can have no place in a European Union that is democratic or that is capable of meeting its climate justice responsibilities. Rejecting fossil fuel influence is vital if the EU is to deliver real solutions to the climate crisis and reduce carbon emissions down to real zero, instead of the corporate greenwashed 'net zero' that relies on fossil fuel industry delay tactics like CCUS.

Read the full report here