The dirty truth about the EU’s hydrogen push

The EU is hyping hydrogen as the miracle that will cure our fossil fuel addiction. The truth is dirtier: hydrogen risks actually extending fossil fuel use, as well as deepening neo-colonial extractivist practices, including the large-scale appropriation of land, water, and energy in producing countries. New infographics by Corporate Europe Observatory and WeSmellGas expose the dark side of the EU’s hydrogen craze – and the firepower of the corporate giants driving it.

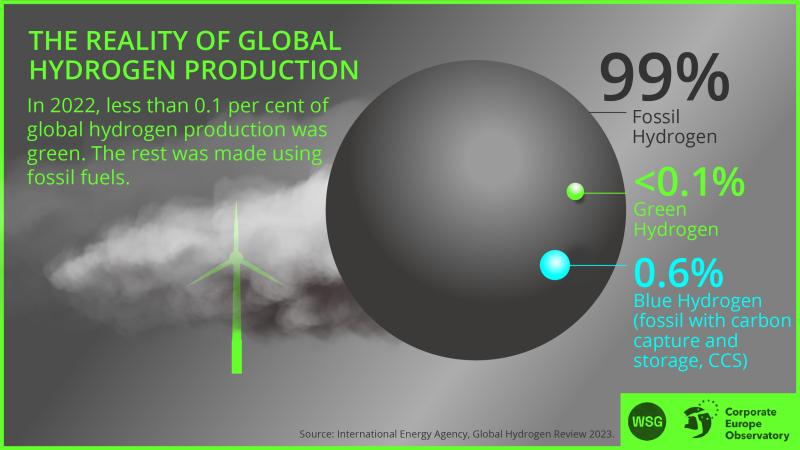

An incredible 99 per cent of globally produced hydrogen is made from fossil fuels, according to the International Energy Agency – the same fossil fuels that are the largest contributor to greenhouse gas emissions and thus to the climate crisis. In 2022 global hydrogen production was responsible for over 900 million tonnes (Mt) of CO2 emissions. That’s more than was emitted by the global aviation industry (almost 800Mt) and significantly more than Germany’s CO2 emissions (635 Mt), the EU’s most polluting economy.

The production of green hydrogen, on the other hand, remains tiny, despite all the fanfare. Green hydrogen is produced through a process called water electrolysis that uses electricity from renewable energy sources to split water into hydrogen and oxygen. In 2022, less than 0.1 per cent of global hydrogen (0.087 million of 95 million tonnes) was produced this way, according to the International Energy Agency’s press office. However, this figure also includes electrolysis powered with nuclear energy; so the actual share of green hydrogen from renewable electricity is likely to be microscopic.

But even green hydrogen, with its squeaky clean image, comes with serious challenges and risks that are not widely known. The inconvenient truth is production of green hydrogen on a large scale requires vast amounts of land, water, and renewable energy (that could otherwise be used to meet local electricity needs).

Blue hydrogen: a climate killer

Then there is ‘blue’ hydrogen, which is also produced from fossils, mostly gas. In 2022 it accounted for 0.6 per cent of global hydrogen production, according to the International Energy Agency. To create blue hydrogen, CO2 from the production process is captured and stored underground (via CCS – carbon capture and storage). If the captured CO2 is used further, it is called ‘carbon capture, utilisation and storage’ (CCUS).

Due to the storing away of CO2, blue hydrogen is often described as a low-carbon, low-emission, or even CO2-neutral gas. But this framing ignores several dirty truths, including the fact that the fossil fuel industry uses nearly three-quarters of all globally captured carbon for so called ‘enhanced oil recovery’ (EOR). EOR entails injecting the captured carbon into depleted oil and gas fields in order to pump out – and ultimately burn – previously un-extractable fossils. In other words: producing even more emissions.

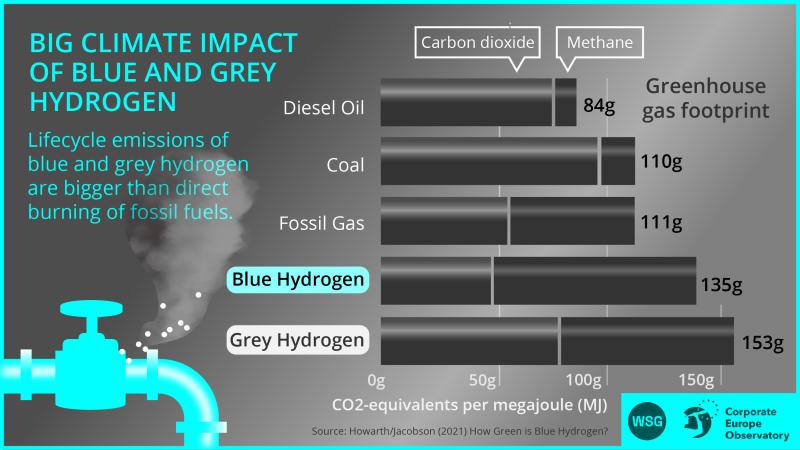

But even without enhanced oil recovery, blue hydrogen’s total greenhouse gas emissions are only moderately lower than those of grey hydrogen (created from fossil gas, or methane, using steam methane reformation). There are two reasons for this: first of all, CCS technologies only capture a fraction of the produced CO2; and furthermore, a great amount of additional fossil gas is used to power the technology, leading to increased methane emissions. Methane is an even more powerful greenhouse gas than CO2, and escapes whenever fossil gas is extracted and transported.

When CO2 and methane emissions are added up – including the upstream ones that occur prior to the CCS process – the climate footprint of blue and other fossil hydrogen is greater than burning fossil fuels directly, according to calculations of US scientists Robert Howarth and Mark Jacobson. “Hydrogen from fossil gas is a terrible idea,” Howarth concludes. (You can learn more about how Big Oil and Gas are hyping CCS to delay climate action here.)

Meet the EU’s hydrogen lobby

With the awareness that hydrogen will continue to be mostly fossil-based in the years to come, oil and gas majors like Shell, Total, ExxonMobil, and their lobby groups are hyping hydrogen as a silver bullet solution for the climate crisis. As a result of their lobbying, hydrogen has become a cornerstone of EU policies and the bloc has set unrealistically high targets for the use of hydrogen, including in sectors like road transport where cheaper and cleaner alternatives are available. With green hydrogen targets likely to outstrip supply, there is a risk that grey and blue hydrogen from fossil fuels will be allowed to fill the gap.

Other polluting industries have jumped on the hydrogen bandwagon to lock in and expand harmful infrastructure, production, and consumption models. Because why reduce traffic, transition to agro-ecological farming, or decommission fossil gas pipelines when you can continue your dirty business with hydrogen?

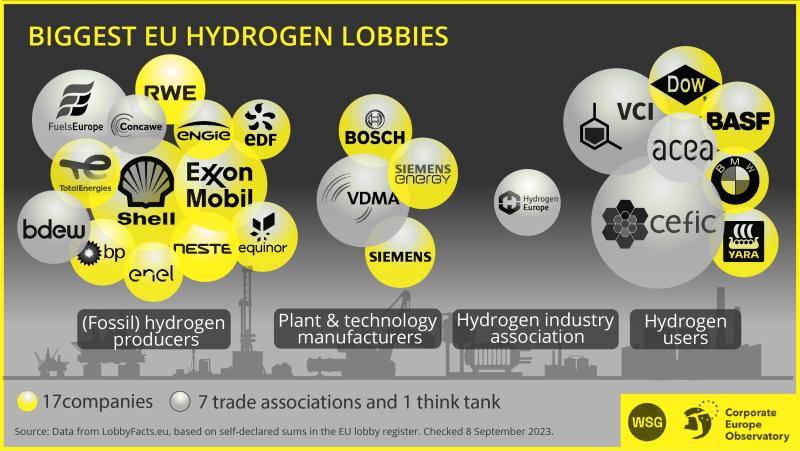

In addition to the fossil fuel industry, the hydrogen lobby also includes:

- Industrial hydrogen users: chemical and fertiliser corporations such as BASF, Dow, and Yara use massive amounts of fossil gas and hydrogen to create their products. Backed by chemical industry lobby groups like Brussels-based CEFIC, they place their bets on green and other allegedly ‘low carbon’ forms of hydrogen to secure their toxic business while greening their image.

- The transport sector: several players position hydrogen as a fuel that will reduce emissions – even though it is widely considered as too energy inefficient to be a climate solution for cars, trucks, and buses. This includes car makers like BMW and car industry lobby groups like ACEA.

- Plant and technology manufacturers: engineering companies like Siemens and Bosch manufacture components for the gas industry, the electrolysers that produce green hydrogen and/ or components for them. They are echoed by trade associations like German lobby group VDMA.

New analysis based on LobbyFacts data shows that in the top 100 EU lobby groups (those paying €1.75 million and more a year for lobbying the EU institutions), there are 25 hydrogen players: 17 companies (Shell, ExxonMobil, Dow, BASF, Robert Bosch, Siemens, TotalEnergies, Equinor, Yara, BP, BMW, Electricité de France, ENEL, ENGIE, Neste, RWE, and Siemens Energy), 7 trade associations (EU chemical industry lobby CEFIC, its German equivalent VCI, oil lobby Fuels Europe, German engineering association VDMA, German energy lobby BDEW, EU car manufacturers group ACEA, and Hydrogen Europe) as well as 1 think tank (Concawe, which is linked to Fuels Europe).

In the EU lobby register, these 25 groups either list hydrogen as one of the key issues they are lobbying on, they held meetings on the issue with the European Commission, have participated in public consultations on the issue, are members of dedicated hydrogen lobby groups such as Hydrogen Europe, or often, all of the above. Hydrogen Europe is considered the most influential hydrogen lobby group in the EU and comprises over 500 companies and associations from along the entire value chain. In addition, there are 13 lobby consultancies amongst the EU register’s 100 top spenders, which have lobbied the Commission on hydrogen and have significant clients from the hydrogen sector. (See Our methodology.)

Spending big on lobbying for hydrogen

In Brussels, the hydrogen lobby is a particularly huge spender.

Together, the top 25 hydrogen lobby groups spend a whopping €75.75 million a year on lobbying the EU institutions.

That is more than what the top Big Tech (€43.5 million) and Big Finance (€38.75 million) lobbies pay (as calculated from a list of the EU lobby register's top 100 spenders. See Our methodology.)

Big Hydrogen’s lobby wins

As a result of Big Hydrogen’s massive lobby efforts, the EU has made hydrogen a cornerstone of its policies, spending billions in public funds to spur the sector. From the 2020 EU hydrogen strategy which kickstarted Europe’s crazy bet on hydrogen, to the subsidy boom (including recovery funds, new state aid rules, and the recent Hydrogen Bank), the hydrogen lobby has achieved plenty of lobby wins.

The 2022 REPowerEU, for example, sets the EU’s 2030 targets for green hydrogen at 20 million tonnes, with half to be produced domestically, and the other half imported. Compare that with the less than 0.087 million tonnes of green hydrogen produced globally in 2022, and you get an idea of how overblown that target is. No wonder it made the Chief Executive of lobby group Hydrogen Europe, Jorgo Chatzimarkakis, “extremely happy to see that our European campaign to make hydrogen big is working”. Shell, BP, TotalEnergies and other fossil fuel members of Hydrogen Europe will happily use the unrealistic targets to sneak fossil-based hydrogen through the back door.

More recently, the hydrogen lobby managed to cripple the EU’s ‘additionality’ rules for green hydrogen, published in February 2023. These require green hydrogen producers to build ‘additional’ new renewable energy installations. But as a result of the industry’s fierce lobbying, the final rules exempt certain installations from this requirement until 2038. This means that hydrogen plants can suck up scarce existing renewable energy capacities for years, risking driving the grid towards incorporating more fossil fuels to fill the gap, exacerbating climate change. (See page 30 in this report for more info.)

This harmful track record of influence is also worrying for ongoing and upcoming lobby battles: from the hydrogen package to the Critical Raw Materials Act, Big Hydrogen has its fingers in every pie.

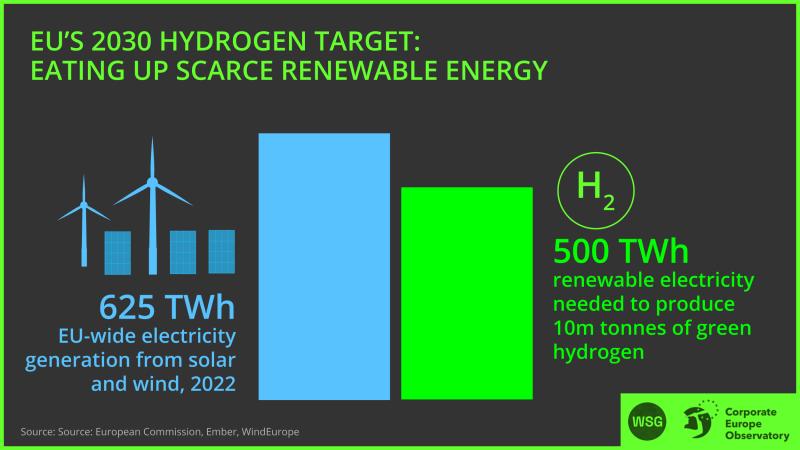

Eating up scarce renewable energy

According to European Commission estimates 500 terra-watt hours (TWh) of additional green electricity will be needed to reach the EU’s 2030 domestic production goal of 10 million tonnes of green hydrogen. That is more than all electricity that was consumed in France (452 TWh) or Germany (484 TWh) in 2022. It is also more than all wind-power generated electricity (412 TWh) and nearly 2.5 times all electricity from solar power (203 TWh) produced in the whole EU that same year.

In other words: the EU’s 2030 hydrogen production goal would eat up over 80 per cent of today’s EU-wide wind and solar generated electricity.

This means a loss of efficiency as one source of energy is diverted to produce another (in fact, green hydrogen contains only around 70 per cent of the renewable energy needed to produce it – the other 30 per cent is lost in the production process). And if the production goal is met, this electricity will no longer be available to green the grid that supplies homes, public buildings, and industry. There is a danger that this will lead to more fossil fuels being burned to cover this shortfall.

The EU’s 2030 import goal for green hydrogen (another 10 million tonnes) raises similar problems. Many of the countries that the EU considers potential export countries produce little green energy. For example, in the Gulf countries, less than 1 per cent of the electricity came from renewables in 2022 (with the exception of the United Arab Emirates with 4.5 per cent). Even Morocco, which has pioneered renewables, the total is still less than 20 per cent of electricity generated – compared to nearly twice that amount in the EU. Algerian energy policy researcher Imane Boukhatem argues: “it would be more logical and just to prioritize the local energy transition needs, as opposed... to exporting green hydrogen and consuming fossil fuels at home”.

The African People’s Climate and Development Declaration, signed by over 500 African civil society groups in September 2023, calls green hydrogen a “false solution we reject” for similar reasons:

“Green hydrogen for export does nothing to increase access for the 600 million Africans without access to energy. Instead it turns our African renewable energy into an exportable commodity and ships our energy overseas... Renewable energy needs to be prioritised for domestic use, not foreign markets.”

Green hydrogen’s massive land needs

Delayed decarbonisation is not the only risk for potential hydrogen export countries. The wind and solar farms for the hydrogen economy also need vast areas of land. For example, with an area of 8,500km2, the Aman project in Mauritania – one of the biggest planned green hydrogen projects in the world – covers more land than many global megacities, including Tokyo, Moscow, or Beijing. In Oman, the government has selected 50,000 km2 for green hydrogen production, nearly one sixth of the whole country!

Green hydrogen’s vast land needs can lead to the displacement of communities and human rights violations. A shocking example is Saudi Arabia’s planned giga city Neom, where huge electrolysers to produce green hydrogen are being built (including for export). Local people have been forcibly evicted from their land to make way for Neom. Several protestors who objected have been sentenced to death because of their resistance to the eviction; and one shot dead by security forces when he protested the demolition of villages. Nonetheless EU member states like Germany, the Netherlands and France have since entered into hydrogen cooperation agreements with Saudi Arabia, seeking to implement joint projects. In March 2023 European Commission Vice-President Frans Timmermans and EU Energy Commissioner Kadri Simson visited Saudi Arabia to discuss cooperating on hydrogen.

Big Hydrogen legitimising repressive regimes

Such cooperations risk reproducing and legitimising some of the world’s most brutal regimes. A fifth of the globally planned giga-scale green hydrogen projects (21 out of 109 projects identified in our database, with a planned production capacity of more than 1 gigawatt of green hydrogen, see Our methodology) are located in states with very severe democratic deficits if not outright dictatorships, often with state-owned fossil fuel majors in the lead. Whether in Egypt, Saudi Arabia, Kazakhstan, or China, green hydrogen projects and international cooperations convey the message of innovative and positive leadership. And yet they risk to preserve the authoritarian and fossil-based social, political and economic status quo in the name of sustainability, warn researchers like Geography Professor Natalie Koch from the University of Heidelberg, who has followed the hydrogen agenda of the Gulf Cooperation Council.

In Morocco, a hydrogen boom could even reinforce the occupation of Western Sahara. With nearly half of its wind and solar energy to come from the occupied territories, researcher Joanna Allan explains that “Morocco is making itself ever more dependent on the occupied Sahara for its energy needs.” She explains that via exports, Morocco will then “implicate Europe and sub-Saharan countries as well in this colonial exploitation”.

There are also repressive tendencies around green hydrogen projects in democracies. In Namibia, for example, President Hage Geingob has issued a stern warning to locals not to interfere in the Hyphen project, a planned mega wind and solar farm to produce ammonia from hydrogen for export. The project has come under criticism from local and regional politicians who feel excluded from the process and from citizens who question the project’s environmental and economic viability. Civil society groups have criticised Geingob for using his power to silence dissent.

Green hydrogen’s water problem

Green hydrogen’s water needs, too, could lead to conflicts. According to industry figures, the production process consumes around 10 litres of ultra pure water (requiring 20-30 litres of seawater or 12-13 litres of freshwater) for every produced kilogram of hydrogen. Large green hydrogen factories would signify an additional new water demand in a situation where the energy sector is already competing with food production as well as drinking water needs. The climate crisis is already worsening freshwater availability in many parts of the world. Communities and civil society organisations like Food and Water Watch in the US are therefore already mobilising against the water-hungry hydrogen buildout.

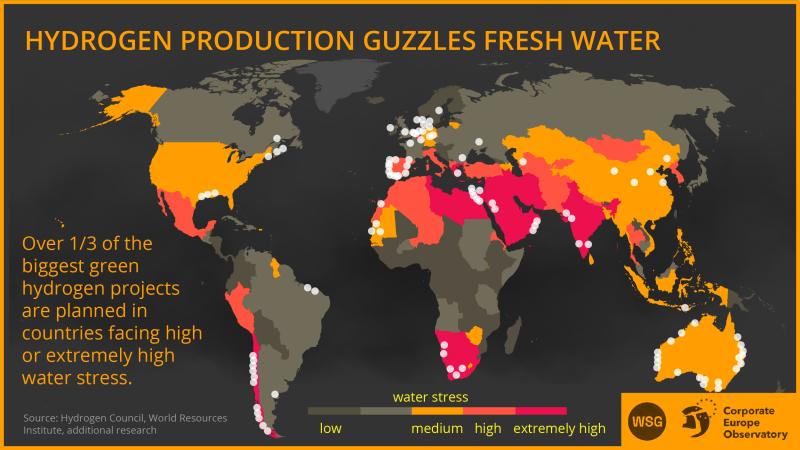

Against this background it is worrying that over a third (37.61 per cent) of the globally planned gigawatt-scale green hydrogen projects (41 out of 109 projects in our database, see Our methodology) are in countries already facing high or extremely high water stress. These countries are regularly using up almost their entire water supply, or large parts thereof. Examples include Oman, Morocco, Namibia, India, Chile, and Spain. Another 38.53 per cent (42 out of 109) of the projects are planned in countries facing medium to high water stress like China and Australia.

Neocolonialism, again

The EU’s global hydrogen quest is thus reinforcing what geography professors Christian Brannstrom and Adryane Gorayeb have called a “global division of decarbonization”: the division between countries that benefit from renewable energy (where multinationals are headquartered and most energy is consumed) and countries that are mostly harmed (because they receive the direct impacts from hydrogen installations).

It also follows centuries-old colonial and extractivist patterns, where communities are dispossessed, resources like land and water are appropriated for (North-Western) European industries while negative impacts like ecological damage and energy scarcity are conveniently outsourced. As Mohamed Adow, the founder and director of climate think tank Power Shift Africa, puts it: “The focus on hydrogen is being driven by foreign interests who want to launch a new and neo-colonial effort to capture and export Africa’s renewable energy potential and water resources (used to make hydrogen) for their own use.”

Standing up against Big Hydrogen

Mohamed Adow also outlined what he considered a “socially, ecologically and economically appropriate use of hydrogen” in Africa: “small to medium scale, for domestic use (not for export), not in water-stressed regions, and to produce fertilizers for food sovereignty rather than for cash crops for export”. His vision could not be further away from the resource-grabbing and corporate controlled hydrogen economy that EU member states, as well as Big Hydrogen, are currently pushing for.

But the EU’s hydrogen hype does not just fail when it comes to global justice and energy democracy. It also fails in its key promise: to help tackle the climate crisis.

Through the de facto scaling up of fossil-based hydrogen for years to come, the hype around hydrogen will drive up emissions and deepen the lock-in of the fossil fuel economy.

It also siphons funds and attention away from much needed meaningful climate action: increasing the energy efficiency of buildings (rather than heating homes inefficiently with hydrogen), transitioning to agro-ecological farming (rather than just greening synthetic fertilisers), reducing traffic and boosting public transport (instead of wasting energy on hydrogen-powered cars) – and the list goes on.

It is therefore encouraging that more and more climate scientists, environmental justice groups, and frontline communities are starting to scrutinise the hydrogen hype. EU policymakers, too, should be wary of the hydrogen gamble, stop the firehose of public money flowing to the sector, scrap its unrealistic hydrogen targets, and stop listening to Big Hydrogen.

Our methodology

Big Hydrogen lobbying: We identified the 100 highest-spending lobbies in the EU lobby register by removing 7 implausibly large entries SidenoteThe EU lobby transparency register has a problem with implausible or dodgy registrations, which is linked to the fact that the register is not legally-binding. More information is available here: https://corporateeurope.org/en/2022/09/complaint-eu-lobby-transparency-register from the LobbyFacts rankings of the highest-declared lobby spenders, and then identifying those with a major interest in hydrogen policy – 25 in total. In the register, they declare lobbying on hydrogen, among other topics, held lobby meetings with the European Commission on the issue and/ or are members of dedicated hydrogen lobby groups such as Hydrogen Europe. Lobby register figures are self-declared by the lobbyists and not subject to independent verification; the EU lobby register is not legally-binding and lacks significant sanction powers. As of May 2022, NGOs, as non-commercial organisations, are no longer required to provide a lobby budget and therefore do not appear in the list of the EU’s biggest lobby-spenders. Data correct as of 8 September 2023 and available here or at LobbyFacts.eu.

Largest planned green hydrogen projects and related problems: The list is based on data from the Hydrogen Council, which they kindly shared with us in June 2023. Their list contained 99 green hydrogen projects (after we counting different phases of projects as one), with a planned production capacity of more than 1 gigawatt (GW) of green hydrogen. We added 10 more giga-scale projects, based on additional research. The total list of 109 globally planned giga-scale projects is likely to be incomplete, none of the sites exists yet, they are in different planning stages, some might never materialise and the figures are self-declared by the project developers.

In order to show how many of the projects are located in countries facing extremely high or high water stress, we used August 2023 data from the World Resources Institute.

To show how many of the projects are located in repressive regimes we used 2023 data by the Economist Intelligence Unit, which takes a broad perspective on whether a country is democratic or not, including electoral and participatory indicators. To the list of countries, which the Unit considered non-democratic (China, Saudi Arabia, Egypt, Oman, Kazakhstan) we added Morocco and Mauritania, which several other leading approaches measuring democracies consider only “partly free” (Freedom House) or simply non-democratic (for lacking free and fair elections). Amnesty International has criticised Mauritania for restricting human rights, including through silencing dissenting voices and the persistence of slavery; regarding Morocco the human rights group has criticised the crushing of dissent and oppositional groups.