Hydrogen from North Africa – a neocolonial resource grab

The reality of EU green hydrogen import plans

بالعربية

Key takeaways

Replacing fossil gas with hydrogen from renewables is set to be a key plank of RePowerEU, the European Commission’s plan to end dependence on Russian gas following the invasion of Ukraine.

As well as shifting gas supplier from Putin to other repressive regimes like Azerbaijan, Israel or Algeria, and building more ports and pipelines to import and transport gas, RePowerEU shows that hydrogen – the latest silver bullet pushed by the gas industry – is to be produced and imported in wildly unrealistic quantities.

Commission Vice President Frans Timmermans recently told the European Parliament “I strongly believe in green hydrogen as the driving force of our energy system of the future,” adding, “and I also strongly believe that Europe is never going to be capable to produce its own hydrogen in sufficient quantities.

“I strongly believe in green hydrogen as the driving force of our energy system of the future. And I also strongly believe that Europe is never going to be capable to produce its own hydrogen in sufficient quantities."

Commission Vice President Frans Timmermans

The Commission has quadrupled its hydrogen targets from 5 million tonnes by 2030 to 20 million tonnes, with half of that to be imported. A special place is reserved for the Southern Mediterranean, which according to previous RePowerEU leaked drafts, is expected to meet up to 80 per cent of imports.

However, a new study commissioned by Corporate Europe Observatory (CEO) and the Transnational Institute (TNI) on renewable hydrogen plans in North Africa shows how unrealistic these targets are from a cost and energy perspective, and how they are already leading to more fossil fuel exploitation.

If the plans do go ahead they will represent the latest neocolonial resource grab, at a time when renewable resources should be used for local energy needs and climate targets rather than helping the EU deliver its climate strategy.

The Southern Mediterranean is expected to meet up to 80 per cent of green hydrogen imports

EU plans for renewable hydrogen in its RePowerEU strategy are not simply about emissions, but part of a broader move to re-establish itself and its corporations as global players within a green high-tech economy.

But given the technical and financial realities of producing and transporting hydrogen, it is unlikely to materialise, and is certainly not where public money should be going.

The EU should immediately revise its RePowerEU strategy, scrap its unrealistic hydrogen import and production targets and vastly increase investment in energy efficiency and renewables to reduce dependency on gas.

Importing hydrogen from North Africa – a realistic plan?

The new study, written by energy expert Michael Barnard and commissioned by CEO and TNI, looks at Morocco, Algeria and Egypt.

Each country is planning to manufacture and export hydrogen from renewable electricity (known as ‘green’ hydrogen), as well as hydrogen-based products. However, oil producing Algeria and Egypt are also exploring hydrogen from fossil gas, using controversial carbon capture and storage (CCS) to reduce emissions (known as ‘blue’ hydrogen).

While national plans are well underway, the study finds that costs of production, not to mention transportation, make EU plans highly unrealistic when the renewable electricity could be used locally.

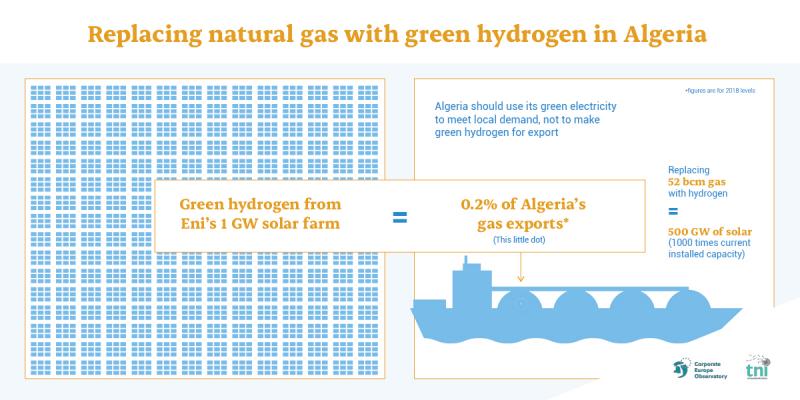

Algeria would need to install 500 GW of solar to replace current gas exports with green hydrogen, which is more than a thousand times what currently exists.

Ensuring the hydrogen is ‘green’ means building new renewable energy sources, but wind and solar are by definition intermittent, with a photovoltaic solar farm on average only delivering between 20-25 per cent of its installed capacity.

That means an electrolyser run directly from a solar farm would only be producing green hydrogen 20-25 per cent of the time, massively increasing its cost.

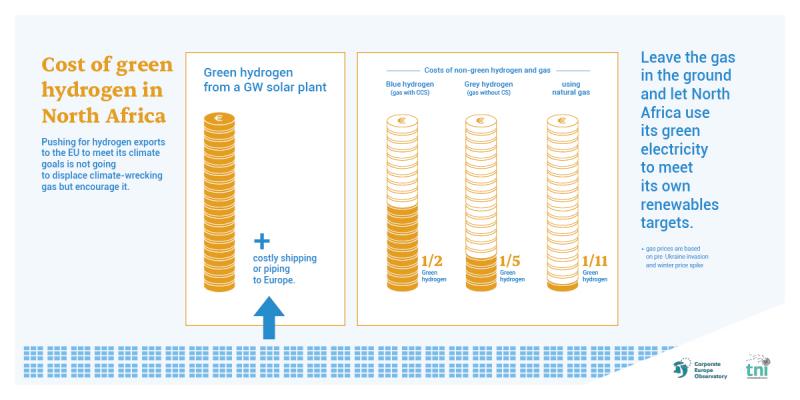

Italian oil and gas major Eni plans to build a gigawatt (GW) solar-powered green hydrogen plant in Algeria and will face this challenge. Estimates from Barnard put the cost at 11 times more per unit of energy than fossil gas, Algeria’s current export priority.

If it switches its exports to hydrogen, as its own government and the EU have suggested, Algeria would need to install 500 GW of solar. This is more than a thousand times what currently exists and would have major implications for land and water use, as well as the raw materials resources.

Connecting the electrolyser to the electricity grid would overcome the problem of intermittent renewable energy, but if it wasn’t generated from additional renewable capacity it would undermine the EU’s criteria for green hydrogen as all three countries power their grids primarily with fossil fuels.

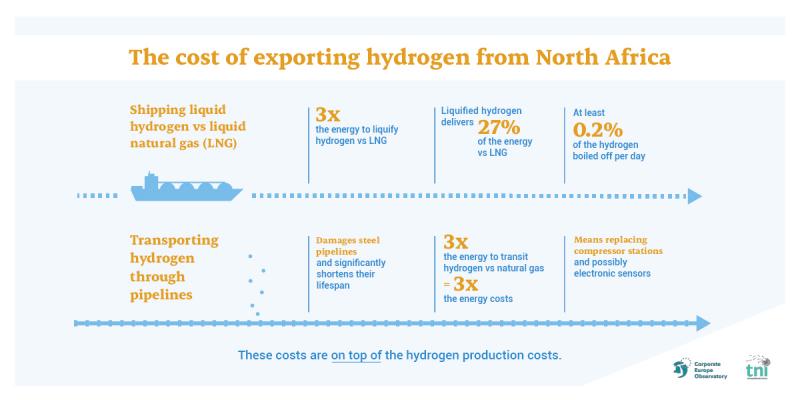

On top of high production costs are high transportation costs. All three countries are looking to export green hydrogen by sea via tankers, but they should be wary as it would take three times the energy to liquify as natural gas, while the same volume of tanker would only carry 27 per cent of the energy.

Blending hydrogen with fossil gas “leads to limited CO2 benefits and to a large increase in energy cost,”

International Renewable Energy Agency (IRENA)

Exporting hydrogen via pipeline is also problematic, as the gas damages not just the pipes themselves but also the electronic equipment within them, meaning the extra cost of replacing them. And as hydrogen takes three times the energy to move than fossil gas (due to its lower density), this translates into tripled energy costs.

Meanwhile, trying to blend hydrogen with fossil gas, as industry is proposing, “leads to limited CO2 benefits and to a large increase in energy cost,” according to the International Renewable Energy Agency (IRENA).

In Egypt, Danish shipping magnate Maersk is exploring green hydrogen-based shipping fuels to replace polluting bunker fuel, but results have been underwhelming according to Barnard.

Both green methanol and green ammonia are toxic to humans and are currently between four and five times more expensive than current fuels (see graphic).

Worryingly, while the EU’s hydrogen agenda in North Africa aims primarily to meet its own domestic needs, it has also been pushing the idea of a ‘hydrogen economy’, with Morocco and Algeria proposing hydrogen for uses such as fuelling cars or industry rather than using the renewable energy for direct electrification.

Egypt is expected to publish its own strategy shortly, helped by the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development, which also keenly advocates for the ‘hydrogen economy’ rather than electrification.

Used for electricity, hydrogen would provide only 37 per cent of the green energy originally used to make it (see graphic).

Despite being widely heralded by the gas industry, switching from fossil gas to hydrogen is not a climate solution for either the EU or North Africa.

Costing as much as 11 times more than natural gas, expensive to distribute by ship or pipeline, is Europe going to be willing to pay for North Africa’s green hydrogen? And will it be a backdoor for fossil fuels?

Backdoor for fossil fuels

While the EU likes to talk about green hydrogen, less than one per cent of Europe’s hydrogen today is green, with 97 per cent produced using fossil gas (‘grey’ hydrogen).

The gas industry claims it can reduce the emissions using expensive and unreliable carbon capture and storage (to make ‘blue’ hydrogen), something the EU supports as a “transition fuel” towards green hydrogen.

In oil and gas producing Algeria and Egypt, blue hydrogen projects are being explored alongside green. Blue hydrogen is still double the price of grey hydrogen, and has the significant problem of high CO2e emissions, despite using carbon capture technology.

The push for green hydrogen and the hydrogen economy has always been supported by Europe’s oil and gas majors, who see it as a back door for hydrogen from fossil gas

Emissions from blue hydrogen would be up to 20 per cent higher than using fossil gas for heat, and potentially more if the captured CO2 is used for enhanced oil recovery as is the case around the world.

These high emissions are caused by leakage when gas is drilled for and transported, as methane – its main component – is a greenhouse gas more than 100 times worse for the climate than CO2 over a ten-year period.

The push for green hydrogen and the hydrogen economy has always been supported by Europe’s oil and gas majors, who see it as a back door for hydrogen from fossil gas: build the hydrogen hype, build economy-wide demand for hydrogen, and when there’s not enough green electricity or electrolyser capacity to supply it, blue hydrogen will step in. They are already involved in these projects and see them as a permanent fixture.

Today the EU is providing financial and regulatory support to domestic blue hydrogen projects, and the new RePowerEU communiqué suggests that the same support mechanisms can be used by its neighbours (i.e. North Africa), while other countries can get support for “Projects of Mutual Interest”, including for “hydrogen transport and CO2 networks and storage,” which underpin blue hydrogen.

Blue hydrogen should not be encouraged. It is an expensive climate disaster that means the continuation of fossil fuel extractivism, with dire environmental and social impacts.

It is not a clean energy solution but a trojan horse for the gas industry that risks becoming a “destination fuel” rather than a “transition fuel”.

Summary of national hydrogen plans

Morocco

-

Morocco aims to replace grey ammonia imports with local green production for its national fertiliser industry, which could be a shot-term measure before transitioning to agro-ecology.

-

Beyond eliminating high ammonia emissions in the short-term, other touted uses of green hydrogen don’t hold up to scrutiny: blending in gas grid, vehicle fuel, electricity, oil refining, export

Algeria

-

Algeria plans to gradually switch its EU exports from natural gas to green and blue hydrogen via its pipelines and LNG terminals, with interest from European partners, but high predicted transit and shipping costs

-

Italian oil and gas major Eni is looking not just at green but also blue hydrogen, with high predicted costs and high methane emissions

Egypt

-

Green hydrogen is seen as a key economic development pathway with Egypt already providing fiscal support measures and an EBRD-supported strategy expected mid-2022.

-

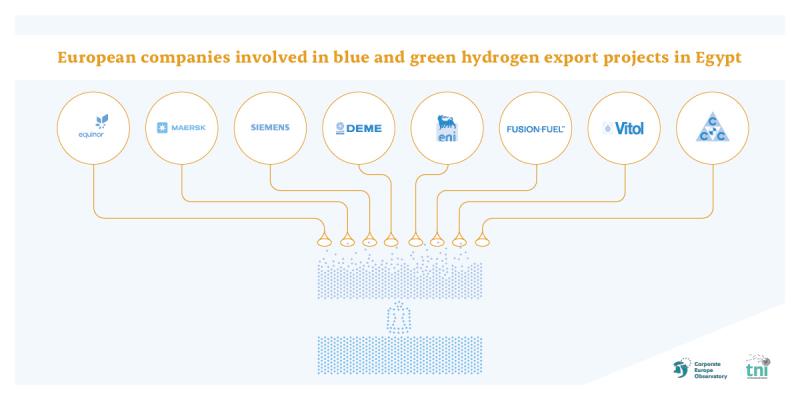

Equinor, Siemens, Maersk, Eni and other European companies are involved in green and blue hydrogen export projects around Suez Canal Economic Zone

EU public funds to foot the bill?

High production and transportation costs make hydrogen and hydrogen products an expensive import.

But according to RePowerEU, the European Commission is creating a European Global Hydrogen Facility. There are few details so far, but according to a leak of a previous draft, the fund is supposed to cover the “initial gap between production costs and sales prices,” and should be up and running by the end of 2022.

Germany had already proposed a similar scheme at the national level.

The European Commission is prepared to cover the “initial gap between [green hydrogen] production costs and sales prices."

Funds for the Facility are supposed to come from the Emissions Trading Scheme (ETS) Innovation Fund, i.e. through the auctioning of the EU’s carbon credits.

But how big will the pot of money be and is this the best use of public funds as the continent is in the midst of a cost-of-living crisis and exploding energy bills?

Spending it on a massive home insulation programme would be far more effective while actually addressing energy poverty in the EU.

Neocolonial resource grab?

Even if the EU does completely cover the costs for its own consumers (which is unlikely given how expensive it will be), is this how North African countries should be using their limited renewable resources?

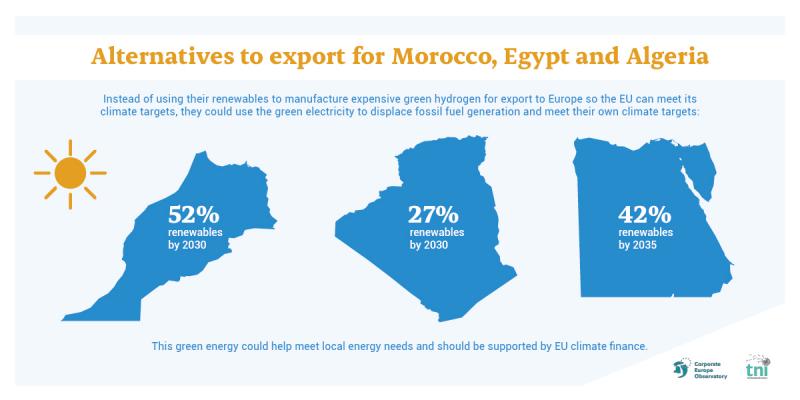

Morocco, Algeria and Egypt all have their own renewable electricity targets under the Paris Agreement, as well as having grids powered by fossil fuels.

The push for green hydrogen is the latest example of the wider neocolonial resource grab in North Africa, hand-in-hand with local elites.

Producing hydrogen and hydrogen-based fuels at high cost and low energy efficiency, in order to export them to Europe, so Europe can pursue its climate goals while they do not pursue theirs, makes no sense.

But that’s precisely what many European companies are exploring, from Dutch Vitol in Morocco to German Siemens in Egypt and Italian Eni in Algeria, the goal is to export the green fuel.

In the case of Belgium’s DEME, its aim is explicitly to help meet its own national and EU climate targets. The German government is also involved in each country for that reason.

This helps explain why the EU and Germany are so happy to subsidise production: European companies will be on both sides of the transaction.

The push for green hydrogen is the latest example of the wider neocolonial resource grab in North Africa, hand-in-hand with local elites, and couched in the same green language as the failed gigantic Desertec solar-for-export scheme.

Global green hydrogen market?

Embracing the hydrogen economy domestically while exporting the idea globally is part of a bigger geopolitical plan that goes far beyond North Africa.

According to the External Energy Strategy, within RePowerEU, the EU wants to “promote a more just and sustainable development across the world,” but its real motivations are to create a global green hydrogen market to boost its own consumption.

It intends to import the fuel from afar afield as Chile and South Africa and is even using green hydrogen to justify new free trade deals with both countries.

The EU wants to “promote a more equitable and sustainable development across the world,” but its real motivations are for a global green hydrogen market to boost its own consumption.

Free trade deals have a proven track record of environmental, social and economic destruction, so what does the EU’s push mean for local development, local businesses, or local energy needs which could be met by renewable energy rather than diverting it into green hydrogen for Europe?

What does it mean for communities displaced and destroyed by extractivism, whose waters are polluted or who have their land taken by mega projects to produce enough green hydrogen for Europe?

Free trade deals – and the creation of a global hydrogen economy – suggest that the pursuit of green hydrogen is as much about EU climate targets as securing new markets and opportunities for European companies abroad.

For the hydrogen industry (i.e. the gas industry), delivering RePowerEU means establishing energy partnerships around the world so European corporations can sell their technology and get access to raw materials, including energy – or at least that is how Hydrogen Europe, the main industry lobby group in Brussels, frames it.

The hydrogen hype being promoted by Frans Timmermans and European industry is more about reinforcing the EU’s global position and providing cover to justify imports than offering a pathway to sustainable development

Hydrogen is already at the heart of the Africa-EU Energy Partnership (and the recent EU-African Union Summit) and a Mediterranean Green Hydrogen Partnership is being established imminently with countries in the Southern Mediterranean. According to a previously leaked RePowerEU draft, it is expected to deliver “trade” of 6-8 million tonnes on green hydrogen by 2030.

Outwardly the partnership talks about local production and consumption, and trade in the region, but peeling back the rhetoric reveals the trade to be distinctly one-directional, from the periphery to the centre.

The hydrogen hype being promoted by Vice President Timmermans and European industry is more about reinforcing the EU’s global position and providing cover to justify imports than offering a pathway to sustainable development.

And if anything, it has also been used by the oil and gas industry to lock-in further fossil fuel development through blue hydrogen, as we have seen in North Africa.

Conclusion

Hydrogen – green or blue – is not a replacement for Russian gas, as envisaged by the RePowerEU strategy, and importing half of Europe’s needs makes no sense economically or from an energy perspective.

The new study shows green hydrogen in Morocco, Algeria and Egypt is expensive to produce, even more expensive to transport, and if used for as a storage medium for electricity would only deliver 37 per cent of the original renewable energy used to make it.

It also represents a monumental grab of clean energy resources when that electricity could meet local development needs and climate targets.

EU money would be better spent on a massive home insulation programme would do a far better job at lowering bills while actually addressing energy poverty in Europe

The EU is also proposing to subsidise European hydrogen consumption through public funds at a time when the continent is in the midst of a cost-of-living crisis and exploding energy bills.

The money would be better spent on a massive home insulation programme would be far more effective at lowering bills while actually addressing energy poverty in the EU.

Worryingly, the EU’s drive for hydrogen is already allowing new fossil fuel projects through the back door in North Africa, which undermine local and EU climate targets and get in the way of a just transition away from fossil fuels.

Rather than perpetuating its neocolonial energy model based on exploiting countries in the global South, the EU should immediately revise its RePowerEU strategy, scrap its unrealistic hydrogen import and production targets and instead vastly increase investment in energy efficiency and renewables to reduce dependency on gas.