Packaging lobby’s support for anti-litter groups deflects tougher solutions

→Please donate today to help us investigate stories like this one. ←

As political support for radical solutions to tackle the scourge of single-use plastics grows, we look at the links between the packaging industry and anti-litter NGOs in Brussels and beyond.

Almost all the plastic ever created still exists in some form, from waste choking marine life, to micro-plastics eaten by fish that end up on the dining table, to the plastics leaching chemicals with unknown consequences. As the problem reaches crisis levels, public pressure to tackle plastic waste has pushed it up the political agenda. In Brussels, Paris, Dublin, Amsterdam, and London decision-makers are keen to respond. But when it comes to tackling the problem at source, the plastics and packaging industries, as well as their allies in the food and drink sector, are on the defensive.

It is much cheaper and more convenient for industry to focus on consumer and individual responsibility for litter and its clean-up, rather than to change production and packaging methods. Not surprisingly then, the packaging industry and its customers in the food and drink sector support various anti-litter campaigns across Europe. Industry does this for several reasons, including to green-wash their single-use packaging products with the veneer of environmental respectability. But this tactic also has other more insidious purposes; significantly, to try to change the popular and political narrative on waste, especially plastics and single-use packaging. Putting litter collection, important as it is, at the heart of the debate on waste puts responsibility for tackling it on local authorities and citizens, rather than industry producers, and gets in the way of tough public policy solutions – such as making industry responsible for its products all along the chain – which might harm corporate profits.

The problem with plastic

We are drowning in plastic. Science Magazine has reported that as many as 8.3 billion tonnes of virgin plastic have been produced to date, with the vast majority of this ending up in landfill or the natural environment where it will take centuries to break down. In our seas and oceans, a World Economic Forum report said that plastics will outnumber fish (by weight) by 2050. Plastics manufacturers’ reliance on climate-destroying fossil fuels as their base ingredient, with added toxic chemicals, lead to incalculable impacts on our bodies and the environment. It is hard to exaggerate the scale of the challenge facing the world, to substantially reduce our plastics use, and to ensure we reuse and recycle as much of it as possible.

Action to tackle single-use plastics is on the political agenda as never before: the European Commission has recently held a consultation on restricting single-use plastics, encouraged by the impact of previous EU rules to cut plastic bag use, which for example in England has reduced the number of bags used by 80 per cent. France has introduced a ban on non-compostable plastic plates and cups, while deposit return schemes are under discussion in several countries.

But industry is fighting back. Reluctant to disrupt profitable business models that are based on simply churning out more and more single-use and disposable products, whether it be coffee cups, plastic forks, take-away containers, or drink bottles; and keen to minimise their responsibility for products once they have left the factory or the shop, industry is trying to shift the blame elsewhere. This is based on the classic economic model of maximising profits by externalising costs: that is, by off-loading the negative impacts of plastics production and waste onto society and the environment. Maintaining this model means industry avoids paying the full cost of its plastics production. One tactic then, is to distract from this issue by putting the responsibility elsewhere. It is a calculated decision by the plastics lobby to put the problem of litter at the heart of the waste debate. If litter and litter collection become the focus of the debate, the emphasis will be shifted to consumers and local authorities to take action. Industry then earns itself some green credentials by voluntarily choosing to fund litter clean-ups and public education campaigns, while simultaneously diverting attention from more far-reaching public policy actions to tackle plastic waste.

This is nothing new. In the 1970s the US’s Keep America Beautiful campaign, funded by industry, presented a narrative around waste and litter that focused on personal responsibility. It mobilised litter-picking drives full of well-meaning people who never realised that behind Keep America Beautiful were the very companies producing the cans and bottles that made up much of the litter problem in the first place – the very same companies opposing reduce and recycle policies. In the alternative world of Keep America Beautiful, disposable or single-use packaging and products have few other negative consequences so long as they are put in the (recycling) bin.

This tactic continues today in the European Union. By funding or setting-up some anti-litter NGOs, by sitting on their steering committees, sharing staff, or commissioning them to produce research to influence public policy decisions, it can be hard to see where industry ends and some NGOs begin. In effect, industry is using these NGOs to try to change the political and popular narrative around waste and plastics use.

The many hats of Eamonn Bates

If there is an event in Brussels on plastics or packaging, you can bet your bottom dollar that Eamonn Bates will be there. The founder of the eponymous lobbying firm, Bates is a regular on the lobby circuit in Brussels when waste, plastics, or packaging are on the agenda. As a previous Corporate Europe Observatory article pointed out, the three clients listed by Eamonn Bates Europe Public Affairs (EBEPA) on the EU lobby transparency register explain this interest: International Paper (a major US paper and pulp company), Serving Europe (a trade association for the fast-food industry including Burger King, McDonald’s, and Starbucks), and Pack2Go Europe (a trade association for the ‘convenience food’ packaging industry). Bates, who is Managing Director of his lobby firm, is also the Secretary General of Pack2Go, and the Secretary General of Serving Europe. Bates holds a European Parliament lobby pass for his lobby firm.

Pack2Go Europe

Of Eamonn Bates’ three clients, Pack2Go Europe is especially interesting. Bates’ lobby firm provides lobby services and “association management services” to the trade body. Pack2Go has an active Brussels lobby operation, holding several high-level meetings with the Commission including to discuss the EU’s plastics strategy in July 2017. A Commission official spoke on “litter prevention” at a Pack2Go meeting in June 2016.

“We want Europeans who eat and drink on-the-go to know that health, safety and environmental considerations have been thought through and factored into production plans. We want them to know that the packs we manufacture are environmentally sound, safe in every way, ethically produced and that end-of-life systems and processes for collection, recovery and recycling have been properly provided for once they have been used".

So says the Pack2Go website. No matter that Pack2Go’s members produce endless single-use plastic wrappers and packaging. “All we ask the consumer to do is to dispose of the used packaging responsibly”, says Pack2Go, as if putting single-use plastic in a (recycling) bin rather than dropping it on the street is the end of concerns about society’s problem with resource over-use.

But look behind the Pack2Go spin that tries to re-brand single-use packaging as environmentally-acceptable, and another agenda emerges. In 2016 the French Government passed a new law which included provisions to ensure all plastic cups and plates should instead be made of biologically-sourced materials so they could be composted. While the French move was not perfect, it was a major initiative to try to tackle the problem of disposable tableware, ie. to challenge the business models of companies behind Bates’ trade associations, Serving Europe and Pack2Go. Not surprisingly, Pack2Go in the shape of Bates, opposed it saying, “We are urging the European Commission to do the right thing and to take legal action against France for infringing European law… If they don’t, we will.” Among Bates’ arguments was that such a measure might lead to more litter as people would not bother to dispose properly of items if they think they will easily compost.

Later, when Green MEPs tried to enable the introduction of further national-led restrictions on specific packaging types, Pack2Go celebrated when the move was rejected by other MEPs. Mike Turner of International Paper Foodservice Europe (International Paper is another of Bates’ lobby clients and until January 2018 it owned Foodservice Europe) who is also current chairman of Pack2Go Europe said at the time:

“Pack2Go Europe has worked tirelessly to explain to MEPs that our packaging is indispensable to the way people live today. That work must go on. The real challenge we must all face is the need to facilitate more and better collection and recycling.”

Most recently, Pack2Go has also been opposing the Irish Waste Reduction Bill which aims to ban some single-use plastics and introduce a deposit return scheme, on the grounds that it would break EU rules on packaging and the free movement of goods. Bates, who was present at a January 2018 hearing on the Bill in the Irish Parliament, was quoted by The Times as saying:

“It is unfortunate more care was not taken by the promoters of the Waste Reduction Bill 2017 to avoid the mistakes made in France rather than put forward a proposal that is legally flawed.”

What is a deposit return scheme?Deposit return schemes (DRS) reward citizens for returning and recycling their can or plastic bottle by reimbursing a small levy paid at the time of purchase. There is evidence that DRS reduce litter, but they also boost both the quantity of plastic collected for recycling, and crucially its quality as it can be more easily cleaned and sorted for reprocessing. But plastic packaging producers dislike DRS as they are required to pay small fees per bottle or can produced to fund the system and there can be additional compliance costs, such as product-relabelling. As Samantha Harding of the Campaign to Protect Rural England explains:

|

What all these examples show is Pack2Go actively opposing tough public policies to try to tackle the environmental legacy of single-use plastics, policies which would affect the financial bottom line of its members. Instead, Pack2Go tries to shift the focus onto litter. No doubt it was as part of these Pack2Go efforts to reframe the environmental problems associated with disposable packaging that it chose to set up the Clean Europe Network.

Clean Europe Network

In 2011, the European Commission undertook a consultation on options to reduce the use of plastic bags. On its agenda was the possibility to allow for charging. In a letter to then Environment Commissioner Janez Potočnik in 2011 which was authored by Eamonn Bates, Pack2Go accused the Commission of a “sort of ‘witch hunt’ against plastics” and of having an “inherent bias against single use packaging solutions”. Bates’ sign-off to Potočnik gives us a clue as to Pack2Go’s future strategy:

“We would be delighted to meet you and your services in the near future to elaborate on paths to obtaining effective solutions to the challenge of littering”.

Enter stage left the Clean Europe Network, a creation of Pack2Go.

The Clean Europe Network, also known as the European Litter Prevention Association, was set up in 2012 and says it coordinates with NGOs and public authorities to “improve litter prevention techniques across the EU”. It is a network of NGOs based in EU member states working towards the goal of “a litter free Europe by 2030”. One of its objectives is to “Provide businesses with opportunities to collaborate with or support the Network” and it is also active in Brussels.

Its board consists of five members: Keep Scotland Beautiful, Gestes Propres (France), Nederland Schoon (Netherlands), Hal Sverige Rent (Sweden), and Mooimakers / FostPlus (Belgium). Three of these organisations (Keep Scotland Beautiful, Nederland Schoon, and Mooimakers) are discussed below; they have been criticised for their links to industry.

The Clean Europe Network was set up by Pack2Go, a fact hailed on its website:

“Pack2Go Europe, took the bold decision to bring us together for the first time in 2012.… It was a useful initiative because we had never met before. We all agreed to set up an association and six months later it was done. Now we are a team! It was also a brave initiative by Pack2Go Europe because it risked criticism from those in industry reluctant to recognise a share of responsibility and from those in the NGO world who don’t think it is intelligent and effective to have all the stakeholders working together for the same objective.”

The overlaps between Eamonn Bates’ lobby outfit, the industry associations Pack2Go and Serving Europe, and the NGO are multifarious. For starters, they all share an office address in Brussels alongside Serving Europe, while their websites look very similar and follow the same format. Additionally, Bates also acts as Clean Europe Network’s Secretary General, while several other EBEPA staff members have also apparently played multiple roles across these organisations:

Silvia Lofrese was listed as part of the Clean Europe Network secretariat in a 2014 CEN publication and until recently, she was also registered as a parliamentary lobbyist for Eamonn Bates’ lobby firm. She also represented Serving Europe at a 2016 conference on food waste. She recently moved to Hume Brophy, another Brussels’ lobby firm.

Marco Vigetti was listed as part of the Clean Europe Network secretariat in a 2014 CEN publication and is elsewhere described as the CEN Programme Manager, but via his Eamonn Bates’ lobby firm email address. At a 2013 conference he apparently presented the plans of CEN on behalf of Pack2Go. He held an Eamonn Bates lobby firm parliamentary pass in 2013-14. His LinkedIn profile reports that he now works for the European Commission.

Gregory Ruessmann was described as being part of the Pack2Go secretariat at this 2015 event and as part of the Clean Europe Network secretariat in this 2014 publication. Ruessmann held an Eamonn Bates lobby firm parliamentary pass for several years.

Considering these overlaps, it is logical that the Clean Europe Network and Pack2Go also share an approach which aims to put litter centre-stage in the political and public debate on packaging waste – one which ensures only limited responsibility falls to industry. This is exemplified in CEN’s ‘expert opinion’ which largely focuses on consumers and the need for education programmes to prevent litter. Bates told us that “The Network has repeatedly called for extended producer responsibility to cover litter prevention activity”. But as CEN’s ‘expert opinion’ makes clear, industry contributions should only be on a voluntary basis. It says: “In our opinion, it is not appropriate to require producers or extended producer responsibility schemes to pay on a mandatory basis for collection of litter and its subsequent management.”

Clean Europe Network’s response

In a series of questions and answers posted on its website following media criticism in 2016, the Clean Europe Network denies being “a lobby ‘front’ for the packaging industry”. The Clean Europe Network asserts that “Pack2Go Europe has no part in our decision-making” and is only an “associate member”. Yet CEN contracts Eamonn Bates Public Affairs Europe to provide “secretariat services” and Bates is Secretary General of CEN while also being Secretary General of Pack2Go and of Serving Europe. Bates was previously on the board of directors of the European Litter Prevention Association, the legal vehicle behind the Clean Europe Network, until at least November 2014. Bates has told Corporate Europe Observatory that as Secretary General of CEN, “I participate in the meetings of the Board but have no vote, and write the reports”.

Bates also told us that CEN “does not have a lobbying vocation per se … the Network does not lobby on behalf of any economic interest.” Nevertheless CEN is listed in the EU lobby transparency register; it holds one European Parliament access pass; in September 2017 it made a presentation to the Commission’s expert group on waste; and it participated in a DG Grow (the European Commission's Directorate General for Internal Market, Industry, Entrepreneurship, and SMEs) stakeholder workshop in October 2017 on biodegradable plastics.

The Clean Europe Network gives an explanation for Eamonn Bates’ dual roles with Pack2Go and CEN explaining that he can simultaneously wear multiple hats because “of his total personal commitment and enthusiasm for our common cause”. Bates told us that his firm has contributed a considerable amount of pro bono time to support the work of the Network and the litter prevention effort because we believe passionately in that objective”. CEN denies any conflict of interest between Pack2Go and the NGO, arguing that “We want the same thing”.

But this is surely at the heart of the problem. When NGOs and industry are so closely associated – when industry sets up the NGO, when there are shared staff, when board members include industry players, when there is a shared policy agenda – it is hard to imagine that the NGO would do anything which was contrary to industry’s agenda. The Clean Europe Network says that it has not lobbied against deposit return schemes, but neither has it actively supported such policies, while some CEN network members, including some of those represented on CEN’s board, have opposed them, as seen below.

Bates’ response to Corporate Europe Observatory’s questions is available here.

Littering methodologiesAt the heart of Clean Europe Network’s mission has been the development of a methodology to measure litter. This is important as the way that litter is measured can affect what public policy measures are put in place to deal with it. Higher litter counts justify more radical public policy action against waste, such as deposit schemes, and green groups argue that littering methodologies should be robust. They argue that simply counting litter per item is not enough and that volume measurements should also be used. After all, a drink bottle has a far larger volume than a cigarette butt or residue chewing gum, and they account for a high volume of plastic waste. Also, simple per item counts of litter tend to show higher numbers of small items such as butts and gum as they tend to get missed by street cleansing and therefore accumulate in the environment over time, making them look as if they are a far more significant litter problem than bottles and cans. The Clean Europe Network’s simplistic littering methodology focuses on per item counts, while also recommending the comparing of photos of sites to ‘grade’ the severity of the litter problem, and undertaking litter ‘perception’ questionnaires of local people. While this might enable qualitative insights into changes to litter patterns over time, there are doubts as to whether this methodology would enable a robust quantitative assessment of how much litter is present, such as would be needed to establish the case for deposit return schemes. |

EU Commission funding

The European Commission funded the Clean Europe Network, via its legal vehicle the European Litter Prevention Association, to develop its littering methodology. In 2014 CEN received funding of €358,414 to develop a “voluntary common system helping organisations and authorities to define litter and how to measure it” among other activities, while in 2016 it received a further €167,653 for “awareness raising”. Presumably it is these grants which has led to CEN’s website claim that it has the “strong backing of the European Commission”.

A Commission official told Corporate Europe Observatory that it had dealt with Eamonn Bates and others representing the Clean Europe Network during the life of the 2016 grant. However, it was only “a matter of weeks or months ago”, long after the 2016 CEN grant had ended, that this official learnt of Bates’ other roles as a lobbyist and with industry associations such as Pack2Go. The official said that according to the eligibility criteria for EU Life funding, NGOs should be “independent, in particular from government, other public authorities, and from political or commercial interests”, and that were CEN to make a further application for funding, the Commission would need to take a “serious look at it”.

Bates told us that “The Clean Europe Network/ELPA is independent from political or commercial interests … The Commission was aware of the links because Eamonn Bates Europe was identified as providing support services and Pack2Go Europe was/is an associate member of the Clean Europe Network/ELPA”.

But considering CEN’s links to Pack2Go and Eamonn Bates’ lobby firm, this surely raises questions about whether its previous EU grants met the independence criteria.

The impacts of the Clean Europe Network’s activities are probably best seen by visiting some of the countries where its members are active. It is there that we see evidence of how industry is working with some anti-litter NGOs, and how some are getting too dependent on industry funding.

Industry funds for NGOs supporting deposit schemesNot all industry is opposed to deposit schemes; some have a financial interest in ensuring that they go ahead, including those who manufacture the reverse-vending machines which are likely to play a central role in such schemes. Tomra is one such company, based in Norway, and it has funded NGOs who support deposit schemes. These include the Association for the Protection of Rural Scotland which runs the Have you got the bottle? campaign which Tomra part-funds, including a trip for journalists, NGOs and retailers to Oslo in 2016 to see a deposit scheme in action. APRS says “This funding is provided on the basis that Tomra has no influence over our campaign strategy, and that if a deposit return scheme is introduced in Scotland there can be no guarantee that this will result in business for them.” Recycling Netwerk, a Benelux-based organisation which plays a significant role arguing for deposit schemes, is also part-funded by Tomra. In neither case is Tomra represented on the boards of the organisations, and both Have you got the bottle? and the Recycling Netwerk have the support of major NGOs in the respective countries. |

Mooimakers in Flanders, Belgium

In Flanders, the Dutch-speaking part of Belgium, there has been political discussion about introducing a deposit scheme for cans and bottles. Yet action on the scheme was postponed when a deal was struck between industry and public authorities to fund Mooimakers.

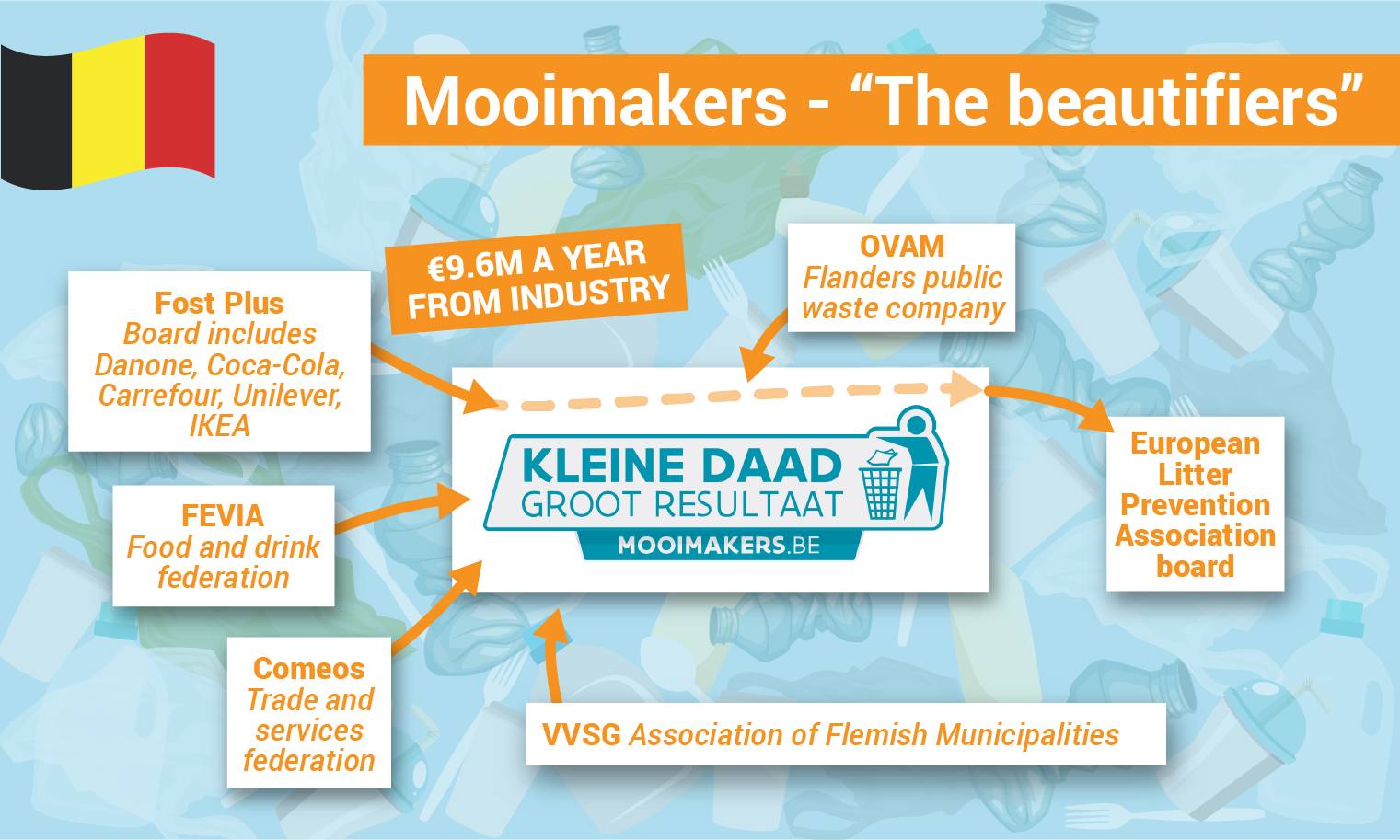

Mooimakers is a collaboration between OVAM (the Flanders public waste company), the Association of Flemish Cities and Municipalities (VVSG), and Fost Plus, an industry body working on recycling whose board members include Coca-Cola, Danone, Carrefour, Unilever, and IKEA among others. (Coca-Cola alone produces 100 billion throwaway plastic bottles each year.) Mooimakers is hosted in OVAM’s building in Mechelen and focuses on litter collection and prevention.

Mooimakers is a member of the Clean Europe Network. Steven Boussemaere, the director of projects and development at industry body Fost Plus, sits on the board of CEN’s legal vehicle the European Litter Prevention Association, as its representative.

Mooimakers calls itself a social movement but its links with industry give a different picture. The deal to fund Mooimakers sees an annual €9.6 million donation from industry to cover the period 2016-18. De Standaard reported that the funds came from Fost Plus, Fevia (the Belgian food industry federation), and Comeos (the Belgian trade and services federation), and they also take up half the seats on the Mooimakers’ steering group. This industry funding is vital to Mooimakers’ viability: of its ten employees, all are funded by industry including seven whose contracts are with OVAM, plus at least one secondment from Fost Plus. The funds will also be used for “direct actions, initiatives, projects, campaigns, studies, surveys”. Such an arrangement surely raises questions of conflicts of interest because OVAM is also actively working on litter monitoring which will lead to a decision about a future deposit return scheme.

A March 2017 report commissioned by OVAM showed that littering had recently increased in Flanders by 40 per cent, but apparently it was not published. This is significant because failure to meet the target of a reduction in litter by 20 per cent in 2022 would increase pressure for a deposit scheme, something which industry vehemently opposes. The report was later re-done and published, and it still showed an increase of litter, albeit at the lower level of 17 per cent. The report showed that the costs of dealing with litter had more than doubled. Later in 2018 there will be an initial evaluation to assess whether the authorities are on track to meet the 2022 target. It is legitimate to ask what influence Mooimakers’ funders and steering group members will have on this process.

This model of industry funding has now been rolled out to the Wallonia and Brussels regions of Belgium too.

Nederland Schoon in the Netherlands

In the Netherlands the Clean Europe Network member Nederland Schoon, which was set up by the packaging industry and waste management authorities, has been active on deposit return schemes. Over time its position has morphed from outright opposition to casting doubt on such proposals.

Nederland Schoon was a member of the sounding board that accompanied recent government-commissioned research into the possible introduction of an extension of the current national deposit scheme to include small bottles and cans. The final report supported such a scheme and that prompted the European Litter Prevention Association Treasurer and Nederland Schoon Director Helene van Zutphen to write a letter distancing herself from its conclusions which is included in the report’s annexe. This placed Nederland Schoon in the same camp as the retail, food and drink, brewers’ and soft drinks industries, all of whom argued that not enough research had been done to establish a significant effect of the scheme. The other environmental NGOs on the sounding board gave the opposite view.

Nederland Schoon receives substantial funding from industry, via Afvalfonds (the packaging waste fund). Afvalfonds is an ‘Extended Producer Responsibility’ organisation where packaging producers (organised in the above industry federations) pay a small amount for the packaging they put on the market. Afvalfonds is responsible for the system to collect and recycle those packs and it gives €5.5 million a year to Nederland Schoon. Nederland Schoon’s board of directors includes representatives from the Dutch retail federation (CBL) and Coca-Cola. It denies being a lobby club for business interests.

At a hearing in the Dutch Parliament in November 2017 to follow-up the research on the proposed extension to the existing Dutch deposit scheme, Peter Swinkels (the chairman of Nederland Schoon and ex-CEO of Bavaria, a Dutch beer brand), said that there was no proof that deposit refund schemes help to reduce litter. Meanwhile the Director of Afvalfonds, Cees de Mol van Otterloo (who incidentally is also a former director of public affairs at Coca-Cola Netherlands,) indicated that if the deposit scheme extension went ahead, it would no longer fund awareness-raising and litter clean-up activities.

So, extending the Dutch deposit scheme could pose an existential threat to Nederland Schoon’s funding base; might this be an explanation for why an organisation that says it wants a cleaner environment instead casts doubt on a solution that would actually help?

Meanwhile in March 2018, while a majority in the Dutch Parliament expressed support for an extension to the deposit scheme, the government has decided to give industry another chance and postponed a final decision until 2020. “Dutch people want a deposit scheme on small cans and bottles, but [Minister] Van Veldhoven postpones the introduction for another two years. Missed opportunity! Time to put the environment above the interests of supermarkets and packaging industry”, Greenpeace told Algemeen Dagblad.

Keep Scotland Beautiful

Across the grey North Sea, another deposit return scheme is on the political agenda.

Derek Robertson is President of the Clean Europe Network, Chairman of the European Litter Prevention Association, and Chief Executive of its Scottish member Keep Scotland Beautiful. KSB is active in many areas of environmental policy in Scotland and its work on many issues is welcomed by other green NGOs. Of its 2017 budget of £12 million, over £10 million was provided by the Scottish Government, most of which KSB re-distributes via its Climate Challenge Fund grants. But KSB is also not shy of corporate funding and there are significant concerns that this funding affects its positioning, particularly on deposit return schemes. Notable industry funders of KSB have included Coca-Cola which supports KSB’s ‘environmental champions’ programme, and trade association the Scottish Grocers’ Federation.

Back in 2015 Keep Scotland Beautiful, “your charity for Scotland’s environment”, was decidedly luke-warm at the proposal of a deposit scheme for Scotland. It told the Scottish Government’s consultation on the matter that: “KSB believes that the scale of the investment that would be required to roll out a [deposit return scheme], and the lack of evidence that it would deliver any significant reduction in litter, means a DRS is not the right solution to the litter problem in Scotland at this time.” Its argument runs that because litter is essentially made up of many different components (cans, bottles, wrappers etc), deposit schemes focussed on single items would not make substantial inroads into the problem.

This was in keeping with previous KSB work. Its 2013-14 survey of litter, which had been commissioned by the packaging industry group INCPEN (which includes Coca-Cola, Diageo, Nestlé, Unilever, Dow, and Tesco among others) had already been used to argue against a deposit scheme. A further study in 2016 (for INCPEN) concluded against action which “[address] just some items”. Another KSB study conducted in 2017 on behalf of the UK government’s environment ministry, sought to create a litter baseline count so as to measure the progress of the Litter Strategy in England. All three reports used the simplistic litter counting methodology and not the more sophisticated volume measurements which can provide clearer evidence for deposit return schemes.

Industry seized on KSB’s positioning for cover in its own opposition to deposit schemes during the 2015 Scottish Government consultation. Coca-Cola quoted KSB’s response as justification for its own negative view on a Scottish deposit scheme. Another industry group, the Packaging Recycling Group Scotland (PRGS) whose members include Coca-Cola, INCPEN, the Foodservice Packaging Association and others, also cited KSB’s litter-count research in its own opposition to deposit schemes.

But environmental NGOs criticised KSB: “KSB is in danger of becoming a creature of the packaging industry, rather than a serious environmental group,” said the director of Friends of the Earth Scotland, Dr Richard Dixon in 2015.

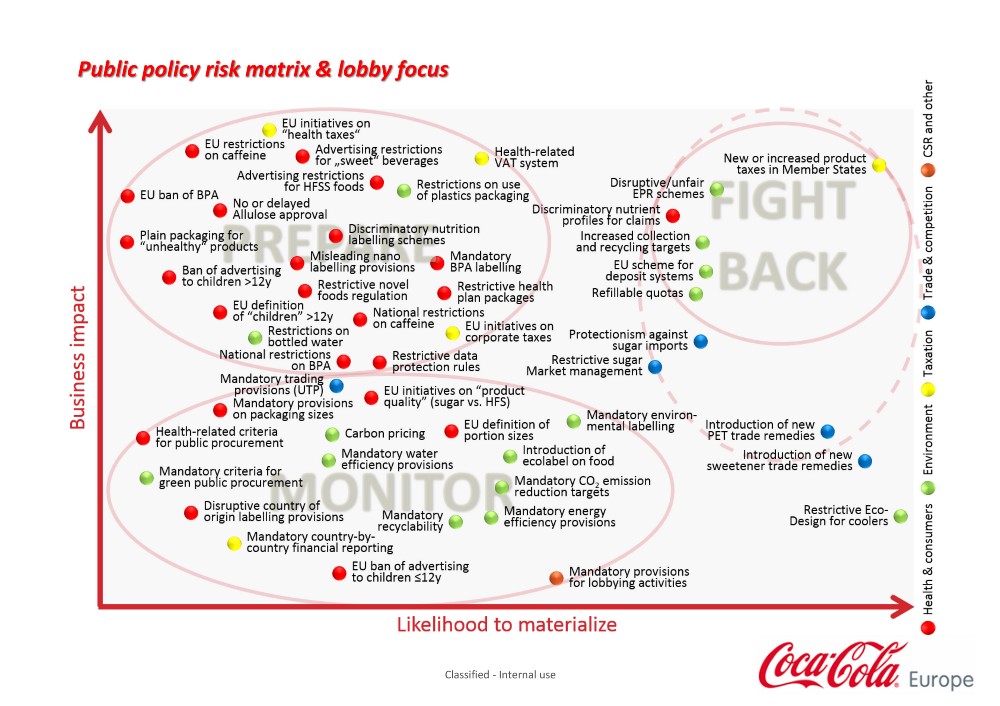

In 2016, US political leaks website DCLeaks was passed a cache of internal Coca-Cola emails which revealed its lobbying strategy. Thanks to Ninjas for Health it became clear how the corporation was responding to the threat it perceived from deposit schemes, while a follow-up investigation by Greenpeace’s Unearthed exposed its lobby operations to “fight back” against such plans by decision-makers in Edinburgh, London, and Brussels.

After weeks of negative publicity in early 2017 Coca-Cola reversed its position on deposit schemes saying: “the time is right to trial new interventions such as a well-designed deposit scheme for drinks containers, starting in Scotland where conversations are underway”.

And what of the position of KSB, now that at least some major industry players were supporting deposit schemes? In March 2017, a comment piece from Derek Robertson on KSB’s website appeared to signal a significant change of tone, saying: “That’s why the debate on a deposit return scheme is so important. It is, beyond doubt, a step forward”, while continuing to refer to KSB’s concerns. Without any sense of irony, Robertson wrote: “a [deposit return scheme] will need to be championed by us all”.

Conclusion

Litter-strewn environments are bad for people and bad for wildlife, but despite what some industry and some NGOs tell us, littering is not just a consequence of people failing to use a bin, but also a reflection of industry reliance on disposable, throwaway products. And while deposit return schemes are not the only answer to the plastics challenge, they can boost recycling and reduce litter. Anti-litter charities do great work in mobilising communities to clean their streets. But too many of these NGOs have been set up by corporate lobby interests, are dependent on corporate funding, share staff with industry, allow corporate interests to set their direction, and / or act as consultants to industry. Sometimes this is just about corporate green-wash which is problematic in itself, but when industry and NGO policy positions become indistinguishable from each other, and when it is about changing the wider political narrative and trying to head-off progressive public policies on waste, that is deeply troubling.

Comments

Very thorough and well-researched article. It highlights a serious problem we also faced with when we started our little volunteer group in 2015 and naively thought that we'll have the support of larger NGOs to keep Scotland really beautiful. In June 2016 we staged an exhibition called "Crapitalism - A Rubbish Exhibition" where we called the big brands to task. You can check it out here: http://leithersdontlitter.org/crapitalism. I'd like to get in touch with the author of this article if possible. She/he can contact us via our website. Thanks.