Commission protects AirBnB lobby paper as ‘commercial secret’

It is no surprise that online rental platform AirBnB and its allies would prefer to keep their controversial political demands to the European Commission private. But it is a disgrace to see the Commission oblige by rebranding these lobbying documents as ‘commercial secrets’ and denying public access. After eight months of wrangling over their release, Corporate Europe Observatory can report the lobbying documents shows AirBnB and its like attacking a whole range of measures used by cities to protect affordable housing.

The European Commission is currently considering whether to issue new guidance to member states on what measures they can and cannot take in relation to short-term online rental platforms such as AirBnB. Information about the lobbying battle currently being waged by AirBnB and its allies is crucial for public debate.

The stakes are high. These online platforms have had a serious impact on access to affordable housing in many European cities as huge numbers of properties are turned into largely unregulated tourist flats, and become unavailable for long-term rental to locals. As Corporate Europe Observatory’s recent report UnFairBnB shows, online rental platforms are fiercely lobbying the EU to defeat the measures cities such as Berlin, Brussels, Barcelona, Paris and Amsterdam have put in place to protect affordable housing in the face of the AirBnB onslaught.

The issue is clearly a matter of public interest, yet the Commission has put up serious obstacles to scrutiny of AirBnb and similar companies. In response to requests from Corporate Europe Observatory for access to information on the short-term rental platforms’ position, the Commission kept a document secret for eight months, claiming it contained “commercial secrets”. Now, the Commission has finally given the document to CEO after months of wrangling and an official complaint.

With the document, the picture we pieced together in the UnfairBnB report is doubly confirmed. The lobbying paper is a kind of political programme of the European Holiday Home Association (EHHA) – the trade association led by AirBnB – and an attack on the main tools used by cities to secure affordable housing in the wake of the rapid expansion of short-term rental platforms.

According to the EHHA:

- The platforms are mere intermediaries, and authorities should deal with the hosts if there is a problem. They claim “online intermediaries provide a neutral hosting service and cannot be held liable or be forced to actively search for illegal activity on their market places”. In other words, they cannot be asked to take any preventive measures in the face of eg illegal listings.

- There should be no authorisation schemes of any sort. Such schemes are not “appropriate regulation”, they claim.

- Collection of “income tax”, says the EHHA, is “a matter between the host and the taxation authorities”, rejecting any notion that these companies should play any role.

- Thresholds, such as a maximum number of days a place can be rented out, should only be allowed under certain conditions, and the EHHA lists defeats in court of the city of Berlin and the Canary Islands as proof that it is illegal under national or European law.

- The platforms reject attempts to apply special rules on commercial hosts as opposed to eg. a host that temporarily rents out a spare room. Such measures “should not be restricting business and enterprise,” the EHHA says.

It is no wonder the EHHA has been hesitant in allowing public access to its policy. Their position laid out in the document is quite outrageous in the light of the problems caused by platforms such as AirBnB across Europe. The EHHA has been very keen on keeping its hardline lobbying aims out of the public domain, and the Commission’s attempt to protect the industry’s political position as a ‘commercial secret’ is disgraceful.

Indeed, the process of trying to retrieve this information was odd from day one. When Corporate Europe Observatory’s access to documents request was first rejected in October 2017, the message was that out of consideration for “commercial secrets” 21 documents, including a document that was to feed into the Commission’s considerations on new guidelines for regulation of short-term online rental platforms, would not be made available.

Commercial secrets? Really? What was clearly a standard lobbying document about public policy, could hardly be regarded as a business secret in the classic sense of the word. Moreover the EHHA is an association of the biggest players in this market, including AirBnB, HomeAway, WIMDU, Schibsted; here they weren’t acting as rivals with trade secrets to protect, but lobbying with a collective position. They had much more to fear from city officials and housing activists knowing their position than from business rivals. In reality the EHHA had political reasons for wanting to keep this document secret, with the Commission apparently keen to help.

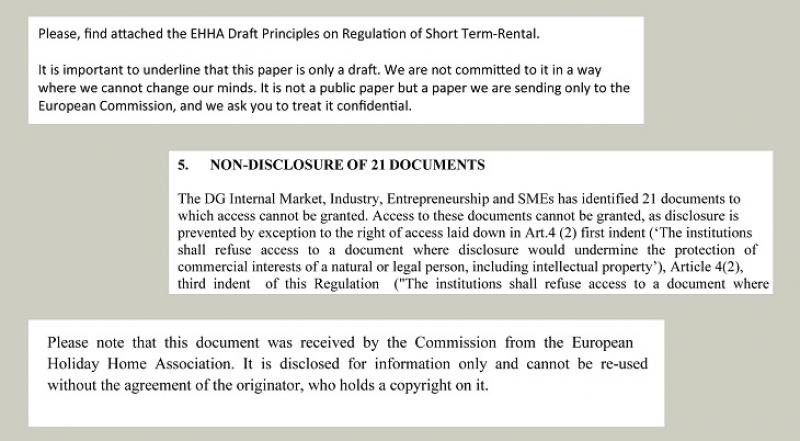

When the trade association first sent its position paper to the Commission in July 2017, it emphasized that it was a draft, and that “It is not a public paper but a paper we are sending only to the European Commission, and we ask you to treat it [as] confidential.” Two months later, though, the lobby group confirmed that this was its final position. Yet even after this the Commission continued to deny Corporate Europe Observatory access for a full eight months, citing the consideration of “commercial secrets”, until we filed a complaint to the Secretariat General. The Commission was finally forced to publish after a tug of war spanning a further two months.

We would expect the EHHA to be hesitant in allowing public access to its policy, considering how damaging and controversial the ‘AirBnB effect’ has been across Europe, impacting liveable city environments and the access to affordable housing for locals. But as for the Commission’s role, there is no basis in the EU rules on access to documents for allowing lobbyists to reframe lobbying positions as “commercial secrets” in an attempt to keep the public in the dark. Such a practice should be explicitly outlawed, and it should not be allowed to slow down public access to documents for months.

And in fact, the Commission is continuing its attempts to keep the document out of the public domain. In the message to CEO in connection with the handover of the document, the Commission states it is “for information only and cannot be re-used without the prior agreement of the originator, who holds a copyright on it.” This last ditch attempt to keep the document secret forms part of an intimidation tactic, CEO believes. A political document such as this is in no way covered by copyright law. The matter will be referred to the European Ombudsman.