Quiet on the set! The EU is negotiating trade deals...

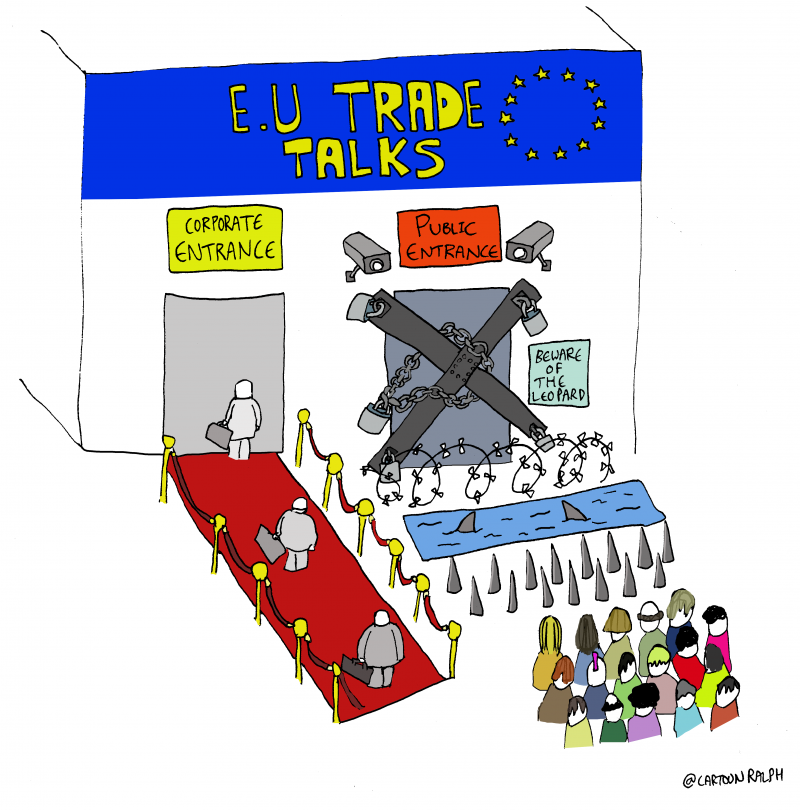

Following calls for openness and public participation, the European Commission now advertises its trade negotiations as transparent and inclusive. But crucial information about EU trade deals are still kept from citizens. Even member state governments regularly complain about being left in the dark. At the same time, corporations continue to call the shots on EU trade talks.

In January 2018, European Trade Commissioner Cecilia Malmström told reporters that “transparency is essential to inform citizens about our trade policy and build trust in what we do”. In May 2017, the script was similar: “I am committed to ensure transparency and engagement in this as in all our negotiations,” Malmström said.

With a view to the EU-Japan trade deal (JEFTA), which is nearing ratification and could be on the EU Council agenda in May 2018, the Commissioner asserted: “Reports of all the latest negotiating rounds with Japan are available to read on our website and so are our new negotiating proposals”.

This claim is unfortunately false. The EU’s lead negotiator for the EU-Japan agreement was in Tokyo for negotiations in both June and October 2017, although the last round of negotiations had already been officially closed. Information about these visits is nowhere to be found on the EU Commission website. So much for commitments and promises... What is happening backstage when the EU negotiates trade deals? Are the actions behind the scenes in line with the official script?

Even member states have to stay quiet when the EU negotiates

According to internal documents from EU member states seen by CEO, even national governments regularly complain about the Commission’s no-information policy around ongoing trade negotiations, which appears particularly strict towards the final stages. Take the Mercosur deal, for example, which is currently being negotiated between the EU and Brazil, Argentina, Paraguay and Uruguay. On 17 November 2017, in a meeting between member states and the Commission on trade, “a large majority of member states who spoke urged the Commission for access to documents and enough time to check them”.

A month before, France had complained about not having been sufficiently informed by the Commission on the Mercosur talks, and Spain had asked to examine the draft chapters of the proposed trade agreement to assess progress. In other words: at this stage, EU member states did not know what the Commission was negotiating in their name, not even concerning controversial market openings in the agriculture sector, which have worried farmers and consumers across the EU.

The Commission’s secrecy seems to be so severe that the French government recently even felt the need to remind it of the importance of timely consultations with member states during all stages of trade negotiations, and in particular during the final stages of negotiations. It seems the Commission does not consider member states as important actors during negotiations.

Big business does still get to shape negotiations

What actors then does the Commission like to see participating on the stage of EU trade negotiations? In December 2017, the institution stressed the importance of considering “the perspectives and insights of a wide and balanced group of stakeholders, ranging from trade unions, employers organisations, consumer groups and other non-governmental organisations”. A closer look at the most powerful actors on stage paints a different picture of the leading roles.

One of these actors playing an influential part is big business. And not only is it an influential actor, but also a privileged one with special access to trade negotiators.

Let’s take another look at the EU-Japan trade deal for this: between 10 January 2014 and 12 January 2017, EU trade negotiators held 213 external meetings with lobbyists to discuss details of the agreement. 89 per cent of those lobbyistswere representing corporations. Not a single one of these 213 meetings took place with representatives of trade unions or with a federation of small and medium enterprises. When asked for more recent figures about lobby meetings during the critical end phase of the negotiations in 2017, the EU Commission refused to reveal who it met in that time, saying that its staff were devoting all existing resources to the conclusion of the negotiations with Japan, making it too burdensome to reveal the apparently too extensive list of lobby groups the Commission had met. In order words, informing the public is regarded as a non-essential ‘nice to have’ when the Commission is not too busy.

Now, those are the meetings on the EU-Japan trade deal that have been happening on the official set. Behind the scenes, representatives of the Japanese business community in Europe are invited to informal Brussels dinners, so they can meet with MEPs from all parties and European Commission officials. The director of those unofficial stagings: a communications agency and its corporate clients.

One influential corporate actor is the EU Japan Business Roundtable, an association of senior executives from leading European and Japanese companies, including Airbus, Mitsubishi, Bayer, BNP Paribas, Nissan, Sony, Ikea, Volkswagen. They have been holding annual meetings with high-level EU and Japanese decision-makers. When we requested more information about the interactions between this corporate lobby roundtable and EU officials in July 2017, the European Commission never responded to our request for documents. Privileged access with the all-decisive sprinkling of secrecy.

In April 2015, the European Commission told corporate leaders that “the European industry [is] regularly updated [about] the developments of the negotiations via a number of dialogues (meetings with Business Europe, sectoral industry dialogues, general meetings with the Civil Society to which industry is also present). Besides, we have a lot of bilateral meetings with either industry associations or interested companies and are always open to any requests we receive.” It seems that for Big Business, the Commission is obviously never too busy.

No wonder, big business welcomed the JEFTA text, especially its regulatory cooperation chapter, which grants companies the privilege to sit at the same table as regulators to define common standards.

And please keep quiet, citizens - we are negotiating!

Whilst the EU is negotiating in close cooperation with big business, it is almost impossible for citizens to follow the process of the negotiations, let alone monitor the details.

As for the EU-Japan deals, even though some documents are available on the Commission website, the most controversial texts remain nowhere to be found. There is no information about ongoing investment negotiations between the EU and Japan for instance. Furthermore, the documents that are presented on the Commission website tend to be the EU’s own textual proposals, so only the documents the EU brings to the negotiation table. The documents coming out of the actual negotiation stage rarely reach the public eye.

In the case of the EU-Mercosur trade deal, for instance, you can easily find the EU’s textual proposals on certain chapters of the agreement online. Only thanks to Bilaterals, can the public access the actual text of the negotiations and take a look at the controversial chapter on the application of food safety, animal and plant health regulations, as well as the chapter on upcoming dialogues. These are very important parts of the text as they reveal EU plans to cooperate with the biggest users of genetically modified crops in the world on… genetically modified crops! Needless to say, this chapter is not made available on the Commission website. Unsurprisingly, the very unpopular word “biotechnology” has no part to play in the Commission’s public display. Furthermore, similar dialogues are taking place on the basis of CETA, the trade deal between the EU and Canada. When asked for more information about those bilateral trade dialogues on energy, finance, public health, etc., the Commission only fully revealed 3 out of the 23 documents requested.

The public is merely regarded as an audience, only meant to see what the Commission has already pre-recorded and deemed appropriate for them.

It is hard not to come to the conclusion that citizens are comprehensively under-informed and even partially misled about EU trade negotiations. This is particularly worrying in light of other major deals the Commission in recent years either concluded (Singapore, Vietnam) or has begun to negotiate (Mercosur, Mexico).

Secret negotiations, away from the public eye, should be a thing of the past, but in the Commission’s script, the usual corporate suspects are cast for the leading roles time and again. Civil society organisations are resigned to the minor parts, at best. EU trade deals impact everything in our daily lives, from the food we eat, to the energy transition vital to combat climate change, the social protections crucial to our well-being, and the financial system we have to save (or not) in times of crisis. Yet, those trade deals are negotiated backstage, out of the reach of citizens and far away from the stage display of public scrutiny the Commission tries to makes us believe in.