Plastic promises

Industry seeking to avoid binding regulations

The plastics industry mounted a significant lobby campaign to influence the European Commission’s recent Plastics Strategy. Industry is now seeking to unpick or undermine key elements of the strategy through lacklustre or non-existing voluntary commitments, or outright opposition. With the Commission likely to publish its proposal to tackle single-use plastic products any day, will it adopt an ambitious approach towards binding regulations on industry?

We are drowning in plastic. Science Magazine has reported that as many as 8.3 billion tonnes of virgin plastic have been produced to date, with the vast majority of this ending up in landfill or the natural environment where it will take centuries to break down. In our seas and oceans, a World Economic Forum report has said that plastics will outnumber fish (by weight) by 2050. Plastics manufacturers’ reliance on climate-destroying fossil fuels as their base ingredient, with added toxic chemicals, lead to incalculable impacts on our bodies and the environment. It is hard to exaggerate the scale and urgency of the challenge facing the world, to substantially reduce our plastics use, and to ensure we reuse and recycle as much and as quickly as possible.

For decades the plastics industry has preferred to focus on litter and its clean-up, rather than addressing some of the more fundamental issues such as product design, manufacturing processes, and developing re-useable or non-plastic alternatives. Corporate Europe Observatory recently exposed how the packaging industry and its customers in the food and drink sector support various anti-litter campaigns across Europe, to both greenwash single-use plastic packaging with the veneer of environmental respectability, but also to try to shift responsibility for tackling plastic waste onto local authorities and citizens.

In the run up to the publication of the much-anticipated Plastics Strategy, during 2017 highly active corporate lobbyists were granted the lion’s share of access to Commission officials. The Commission also proactively reached-out to key plastics industry lobby groups, in order to try to secure voluntary industry commitments to support its own targets, but the industry response was lacklustre. Since the publication of the Commission strategy, industry has been given further opportunities to make voluntary commitments to boost the amount of recycled content in plastic products, but again with little result. Industry remains opposed to key elements of the Strategy.

As the Juncker Commission enters its final year in office it is make or break time for its Plastics Strategy commitments. It is time to recognise that the collaborative approach with industry has failed and to deliver on its promises for ambitious new legislation.

Industry’s lobby access on Plastics Strategy

Ever since the Commission launched the roadmap towards its Plastics Strategy in January 2017, plastics has been a hot topic for industry lobbyists who have poured through the doors as officials started the delicate process of drafting the proposal.

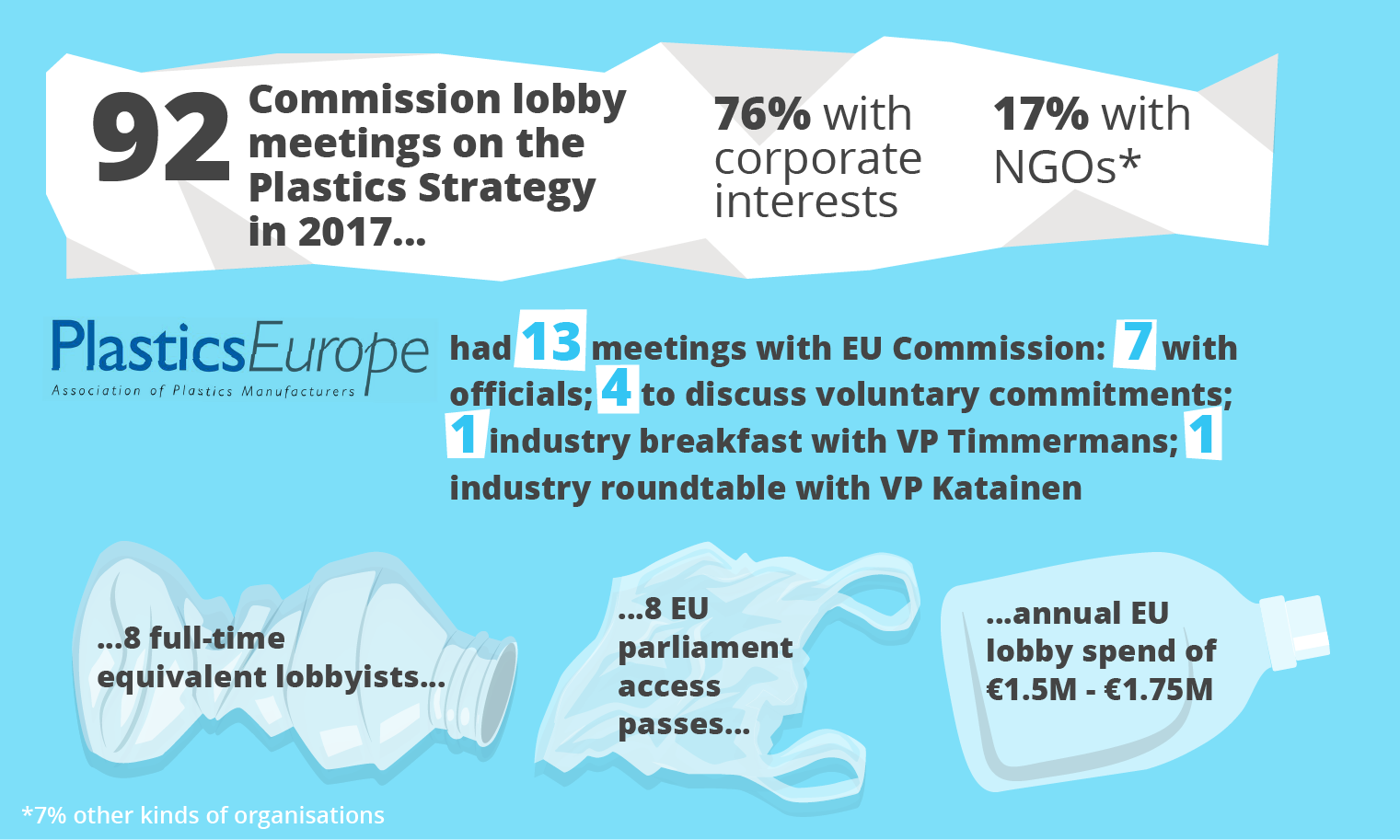

In the 12 months from the launch of the roadmap to the publication of the final strategy in January 2018, officials in the two lead departments, DG Environment and DG Grow (which is responsible for industry and the internal market), held 44 lobby meetings on the Plastics Strategy and 89 per cent (39 meetings) were with industry. Only 3 of meetings were held with NGOs and 2 with others. Adding in meetings with Commissioners, cabinet members, or directors-general, plus those held with Secretariat-General officials, brings the total number of Commission lobby meetings on the Plastics Strategy in the year before it was published to 92. Of these 92, 76 per cent (70 meetings) were with corporate interests and only 17 per cent (16 meetings) with NGOs. This data can be viewed here.

PlasticsEurope led the charge with a total of 13 meetings with Commission. These included 7 with officials, and a 4 further meetings to discuss the process to develop voluntary commitments by industry to be included within the Commission’s own strategy (see below). PlasticsEurope is one of Brussels’ biggest lobby groups, deploying the equivalent of 8 full-time lobbyists and holding the same number of European Parliament access passes. Its members include all the big names in chemicals and petrochemicals: BASF, Borealis, Dow Europe, ExxonMobil Chemical, Ineos, Novamont, Solvay, and many others. PlasticsEurope’s self-declared EU lobby spending figures indicate it has an annual lobby budget of €1,500,000 - €1,749,000 (2016 figures; 2017 figures not yet available). It shares an office building with CEFIC, the European Chemical Industry Council, with whom it shares many interests and collaborates closely. 2015 leaks of PlasticsEurope’s and CEFIC’s lobbying strategies on chemicals in plastics exposed how the undermining of science had been an effective advocacy strategy. CEFIC is one of Brussels’ highest-spending lobbyists and in 2017 had 5 meetings with the Commission on the Plastics Strategy alone.

Other corporate lobbies with multiple meetings on the planned Plastics Strategy in 2017 included the trade association Cosmetics Europe with 7 meetings and Dow, the chemical company, with 4 meetings.

Additionally, a series of ‘stakeholder’ workshops were held during 2017 by DG Environment (eight workshops) and DG Grow (three workshops) on a variety of topics including single-use plastics, packaging, marine litter, deposit schemes, and others. While the attendance lists have not been provided for all of these workshops, the information available indicates that corporate interests again dominated and that PlasticsEurope attended at least some of them.

There were several other corporate gatherings on plastics in 2017. One took the form of a breakfast meeting for industry chief executives with Vice-President Frans Timmermans and was held before the Commission-hosted conference Reinventing plastics – closing the circle in September 2017. Attending this private breakfast were some familiar corporate names including PlasticsEurope. Another event was a round-table with Vice-President Katainen in March 2017 where PlasticsEurope and others were again present.

Of course, NGOs were active in 2017 in the run-up to the launch of the plastics strategy, but given industry’s overwhelming access, the Commission cannot have been in any doubt about the demands of corporates with an interest in the plastics supply chain.

Voluntary industry pledges go missing

A leak of the European Commission’s draft Plastics Strategy found its way into the public domain in October 2017, with an eye-catching line at the top of page six: “[add here possible announcement of voluntary commitments by Plastics Europe]”. Yet when the final strategy was published in January 2018, there were no industry commitments included. What happened?

Over several months the Commission, specifically DG Environment and DG Grow, had been negotiating with industry players to produce some voluntary commitments for inclusion in the strategy, specifically PlasticsEurope (whose industry members produce 90 per cent of the polymers produced in Europe), European Plastics Converters Association (EuPC, which represents plastic manufacturers and processors), and Plastics Recyclers Europe (PRE, representing the plastics recycling industry). The Commission had already committed itself to a target of all plastics packaging to be recyclable by 2030 and was keen to secure industry cooperation.

The Commission must have thought this was a promising strategy. After all, several cross-industry platforms had been set up and visibly championed by industry with a view to developing some voluntary pledges and actions, including on polyolefins and on polystyrene. But voluntary targets and commitments represent a classic lobbying tactic, now adopted by the plastics industry: they can produce the appearance of taking action on an issue and crucially, might just convince public authorities not to implement tough regulation and mandatory rules. However, light-touch regulatory approaches by the Commission, for example for the diesel car industry or alcohol labelling, have proved to be deeply and notoriously problematic.

Correspondence and minutes released by the Commission to Corporate Europe Observatory via access to documents requests show that there was a lack of common agreement between industry players on joint commitments to be included within the Plastics Strategy. In November 2017, an email exchange between the Commission and industry players indicates that the Commission was eager to discuss voluntary commitments with industry: “The sooner we, all, will be able to meet and discuss, the better!”. Yet there is a split within industry: while PlasticsEurope was producing drafts (the eighth version was circulated), the EuPC appeared to want to distance itself from some elements.

At the same time DG Environment emailed PlasticsEurope’s Executive Director in quite frank terms about the draft document: “Thank you for sharing this "work in progress", which we got just in time to reassure our upper levels of hierarchy that your efforts are ongoing and congratulations for the work done so far. However let me also share our feeling that there is still a long way to go until this would become the "ambitious and credible" commitment that we are looking for from value chain participants.”

Two further meetings were held with industry in December 2017 but meeting reports make clear that “full alignment hasn't been reached” and that while the Commission was welcoming progress made, it was also stressing that “a revised version [of the voluntary commitments] with quantitative targets and precise time-frame was needed and should be shared as soon as possible”. By the time a final meeting was held on 8 January 2018 it was clear that, with the Commission’s Plastics Strategy due for imminent publication, time had run out for industry’s voluntary commitments to be included.

The Commission published its strategy on 16 January 2018, and restated its target that “By 2030, all plastics packaging placed on the EU market is either reusable or can be recycled in a cost-effective manner.” While industry’s voluntary commitments were not included within the Commission’s strategy, they were self-published on the same day.

PlasticsEurope’s voluntary commitment was substantially weaker than the Commission’s; the industry expressed the “ambition” to reach 60 per cent reuse and recycling for plastics packaging by 2030, saying “This will lead to achieve our goal of 100% re-use, recycling and/or recovery of all plastics packaging in the EU-28, Norway and Switzerland by 2040”. “Recovery” in this context means energy recovery, also known as incineration, which is controversial and highly damaging for health and the environment. PlasticsEurope’s “general commitments” include prevention of plastic pellets in the environment, and low-hanging fruit such as “raising awareness” and a focus on litter prevention. It places most emphasis on the voluntary industry platforms, although clear action plans were missing. As Politico pointed out at the time, PlasticsEurope said it would “increase efforts” to make it easier to reuse and recycle plastics but made no firm commitment to boost the use of recycled content in products.

The voluntary commitment by other industry players, including EuPC and PRE, also appears to be 10 years behind that proposed by the EU. While the Commission’s target is that “By 2030, more than half of plastics waste generated in Europe is recycled”, industry says it will “launch Circularity Platforms aiming to reach 50% plastics waste recycling by 2040”, although producers of PET plastic (often used in bottles) specifically committed to recycling and reusing of 65 per cent of its packaging by 2030.

Industry fails to pledge action

As the Commission could not include industry’s voluntary commitments in its strategy as originally planned, and crucially neither industry pledge included commitments on minimum content targets which the Commission had been pushing for, the Plastics Strategy announced a pledge scheme to encourage a wider set of corporate players to make commitments to boost the uptake of recycled plastics. The Commission’s objective is to ensure that by 2025, 10 million tonnes of recycled plastics find their way into new products on the EU market.

However, at least by early May 2018, more than three and a half months on from the launch of the Strategy, no pledges had been received, although a number of companies were said to be “preparing” them. Instead there have been lobbying calls from BusinessEurope, the corporate world’s most significant EU lobbyist, for there to be “flexibility” on the 30 June 2018 deadline, with a strong expression of support for such voluntary approaches. When BusinessEurope gets involved, it usually means that it is considered an issue for industry across sectors.

The Commission’s strategy made clear that “Should the [pledged] contribution[s] be deemed insufficient, the Commission will start work on possible next steps, including regulatory action.” In other parts of the world such as California, legislation is in place to require 25 per cent minimum recycled plastics content in new packaging products, providing a clear goal and a boost to the recycling industry. Given the urgency of the situation, a legislative approach, as opposed to reliance on industry promises, is far more likely to deliver change.

Industry opposed to single-use bans and new producer fees

One of the most talked-about elements of the Commission’s approach is its commitment to introduce legislation on single-use plastics, likely to take the form of a list of products (such as coffee stirrers, cotton buds, drink straws, and others) which would be banned outright, and other products for which member states would be obliged to substantially reduce use and oblige industry producers to pick up the costs of their collection and treatment, so-called ‘extended producer responsibility’ schemes. This follows the success of existing EU rules to cut plastic bag use which, for example in England, has reduced the number of bags used by 80 per cent.

The Juncker Commission is on a tight deadline to publish a legislative proposal on single-use plastics before the end of May 2018 when it will enter its final year in office and time will start to run out for the EU’s law-making process. The proposal is expected to be signed-off at the Commission College meeting on 23 May.

Under the Commission’s so-called 'Better Regulation' decision-making process however, all new legislative proposals must be accepted by the Regulatory Scrutiny Board and that requires an impact assessment. The 'better regulation' system – put in place after heavy lobbying by business associations – has been criticised as a mechanism for corporations to weaken or hamper the introduction of new rules that could affect their profit margins. Sure enough, in April 2018 according to Politico, the Regulatory Scrutiny Board “slammed” the Commission’s proposal on single-use plastics due to “weak data”, among other reasons. More recently, the Regulatory Scrutiny Board is said to have now accepted a revised impact assessment for the single-use plastics proposal, although it is not precisely clear how ambitious the Commission was ultimately able to be. A leaked version received by Politico indicated that several types of single-use plastic products were in the Commission’s sights, either for outright bans, or to become part of ‘extended producer responsibility’ schemes, but we will only know for sure as and when the final legislative proposal is published.

Nonetheless, business has lost no time in slamming the leaked proposal in familiar ways: “We are concerned about some very far-reaching proposals … Rather than a ban, it is better to focus on the current voluntary pledging campaign to make plastics more circular”, said BusinessEurope. The packaging industry lobbyist Eamonn Bates was quoted as saying: “Marine litter is a major problem and it must be tackled. But product bans are not the solution … This Commission is simply looking for a few ‘fall guys’ for the press headlines rather than action based on evidence.”

Politico also said that businesses were warning that “putting pressure on producers with a ban and extending the scope of producers’ responsibility to littered items” will “discourage them to engage with the voluntary campaign”, surely another sign that they intend to play hardball.

Plastics tax off the agenda

Given industry's obstructing tactics on other elements, unsurprisingly it is fighting back against another element of the Commission’s plastics strategy, namely a plastics tax.

A plastics tax was first mooted by Commissioner Oettinger who is responsible for the EU budget and is concerned about how to deal with the UK-sized hole in member states’ EU contributions post-Brexit. The final published Plastics Strategy did include a vague commitment that the Commission would “explore the feasibility of introducing measures of a fiscal nature at the EU level”.

Such a tax is clearly opposed by the plastics industry and its allies. PlasticsEurope said: “We do not believe that this would be reasonable.… A new tax on plastics, plastic products or products containing plastics would be very complicated. In the end, the consumer would have to pay for it.” BusinessEurope also did not mince its words in a March 2018 letter to the Environment Minister from Bulgaria (which currently holds the rotating EU Council Presidency): “In our view, if there is one way to kill off appetite for investment in research and innovation in [sic] circular economy, it is to raise a non-material tax of which the revenues flow into the general state coffers”.

The Commission hosted a ‘stakeholder’ workshop to explore the options for a plastics tax in March 2018 but industry players who attended were very “defensive” on the matter. A Commission document, seen by Corporate Europe Observatory, summarised views from this event thus: “The introduction of a dedicated new tax at EU level would be problematic from a competitiveness and subsidiary angle”. As the majority of those attending were NGOs who were largely positive about the idea of a plastics tax, this seems a strange way to summarise the debate! Certainly now an EU-wide tax on new plastics does not look likely anytime soon; disappointingly, Oettinger’s May 2018 EU budget announcement only proposed introducing a “national contribution calculated on the amount of non-recycled plastic packaging waste in each Member State”, which places the emphasis on recycling rather than a reduction in overall plastic production.

Conversely, while opposing a plastics tax, industry has not been shy to request public funding to support its initiatives. For example PlasticsEurope’s voluntary commitments came with the caveat that the EU should “mobilise public funding (such as Horizon 2020) to encourage and stimulate innovation in plastics”, a demand echoed in at least one meeting with the Commission. This is despite the fact that under Horizon 2020 (the Commission’s seven-year research programme) over €250 million has already been made available for plastics research, with an additional €100 million on its way for 2018-20, through which industry and other sectors benefit. As part of its development of the successor programme to Horizon 2020, the Commission is considering scaling-up research funding for targetted “missions”. “Plastic free oceans” is one such mission proposal, and if agreed, could see funding of up to one billion euros, with industry again likely to be among prime beneficiaries of these public funds.

Uncoordinated commitments, coordinated messaging

While different industry players were not able to come up with a coordinated package of voluntary commitments to present to the Commission for inclusion in the Plastics Strategy, they have been singing from the same hymn sheet on other matters.

Across the board, PlasticsEurope, the European Plastics Converters Association, and Plastics Recyclers Europe, have been actively arguing to maintain the EU internal market legal base for the EU Packaging & Packaging Waste Directive and all its amending acts. This might seem a technical point but is a way for industry to try to ensure harmonised rules across all 28 EU member states, and crucially also to head off action by member states which might wish to go further than the EU, say, by banning additional products.

For example when in 2016 the French Government passed a new law which included provisions to ensure all cups and plates should be made with biologically-sourced and compostable materials rather than plastic, packaging lobbyist Eamonn Bates opposed it saying, “We are urging the European Commission to do the right thing and to take legal action against France for infringing European law…. If they don’t, we will.” He has similarly criticised the Irish Waste Reduction Bill which aims to ban some single-use plastics and introduce a deposit return scheme, on the grounds that it would break single market rules on packaging and the free movement of goods.

Throughout their documents industry talks of “increasing circularity and resource efficiency”, “a more sustainable production and consumption of plastics and plastic products”, and “contribut[ing] to emissions reduction”. Of course these are good and desirable aspirations, but coming from the plastics industry are also code for ‘let’s keep on producing more plastic products’. Most of industry interprets notions of a ‘circular economy’ and ‘resource efficiency’ to mean producing lighter products, reusing resources to get more value out of them, and finally burning them to produce energy. Plastic as a lightweight product generally compares favourably with packaging alternatives when looking at, say, greenhouse gas emissions from transport. But this fails to recognise the huge amount of fossil fuels used in plastics production in the first place and the extent to which plastic packaging drives the global food economy.

There is an imperative to develop alternatives to plastic, for packaging and other applications, moving away entirely from disposable and single-use products, while considering the full environmental impact of plastic production and waste. In the waste hierarchy, while recycling and reuse are seen as positive, it is reduction of use which is the most important goal. But the plastics industry can be expected to keep fighting against any regulations which seek to reduce in the amount of plastic in circulation around the world.

Conclusion: words not deeds

The industry response to the Commission’s Plastics Strategy has not been flashy or eye-catching, and it has not come out ‘all guns blazing’ to oppose it. Rather it has been welcomed in broad terms by the plastics and other industries, who are undoubtedly aware of the pitfalls of being on the wrong side of public opinion. But in concrete terms, it is no doubt hoping to delay or even derail legislative efforts or otherwise throw a spanner in the works.

With the Commission due to publish its single-use plastics legislative proposal any day now, we will soon know the extent to which the industry has managed to throw it off track, or whether the Commission remains committed to ambitious action. Subsequently, the lobbyists will no doubt pursue the legislation down the line and shift focus to the Parliament and member states.

We know that when the Parliament and Council discussed the plastics bag ban a few years ago, they were subjected to serious industry lobbying on the topic, with lobbyists joining forces with the MEPs and member states unwilling to take action. It is likely that the industry, including producers of single-use plastic products, are already gearing up for a similar fight.

Comments

Majority of all energy recovery plants in Europe are in the most "green" countries being Germany, Denmark, Austria..No it is not harming the environment, it is helping society to get rid of its trash as no landfil exists it these countries anymore. Banning incineration is like if we would ban cars because they burn fossil fuels. If all countries in Europe would at least recover the energy from incinerating their waste instead of landfilling it, we could save as much oïl as Germany is consuming per year. Still not convince ?