What the Steelie Neelie case tells us about commissioners’ ethics

The latest revelations about ‘Steelie’ Neelie Kroes show that, when it comes to ethics and transparency, the Commission is complaisant about conflicts of interest and far too relaxed about the risk of corporate capture.

Dutch Neelie Kroes, former EU commissioner for competition (2004-2010) and the digital agenda (2010-2014), has admitted that she did not include her long-term directorship of Mint Holdings (2000-2009) in her Commission declaration of interests when she should have done. The off-shore firm is based in the Bahamas for tax purposes and aimed to buy assets from US energy, commodities, and services company Enron, though never actually made the purchase. A statement from her lawyer says:

“My client agrees that formally she should have declared this directorship … Mrs Kroes will inform the president of the European commission of this oversight and will take full responsibility for it.”

Kroes’ arrival in the Commission

Kroes’ breach of the ethics rules is serious and two-fold: she apparently thought her directorship of Mint Holdings had ended in 2002, in which case she should still have declared it as a past role. However, her directorship did in fact only end in 2009, a point at which Kroes had already been a commissioner for over four years. She thereby breached the code of conduct rules which ban commissioners from holding outside directorships. Failing to declare this role, Kroes denied MEPs at her nomination hearing in 2004 the opportunity to quiz her on the Mint Holdings links as well to question why she considered it appropriate to be involved with an offshore company. Considering that her Commission portfolio was competition policy - which plays a significant role in regulating business interests - Kroes' neglect to declare the position also placed her in a possible conflict of interest situation.

The BahamasLeaks exposé published by the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists last week brought to light this latest scandal around ex-EU commissioner Kroes. But the case also raises further questions around the level of oversight of commissioners' declarations of interests which the Commission exercised back then, as well as now. A Commission spokesperson said:

“We don’t have a secret police service that can be sent out to the Bahamas or elsewhere to track down information we haven’t been given”.

However, some form of oversight did take place at the time. According to the Wall Street Journal, DG Competition reviewed Kroes' outside interests before her confirmation hearing with MEPs. This review was not published, but it was said to suggest that had she been a commissioner in the previous college between 1999-2004, she would have had to rescue herself from as many as 35 merger and anti-trust cases which involved previous corporate employers of hers. It seems this was the reason she listed a long list of corporate posts from the previous decade in her official CV, including, among others, positions on the boards of Royal P&O Nedlloyd, New Skies Satellites, Thales Netherlands, MM02 and Volvo. At the time the Wall Street Journal wrote:

“EU officials acknowledge that they have never dealt with a commission candidate with such extensive business ties - and potential conflicts.”

Revolving door for incoming commissioners

Nevertheless, Kroes did apparently still not disclose all of her previous private sector roles in her 2004 declaration of interests, an omission that included her 1996-1997 lobbying for arms manufacturer Lockheed Martin, which itself had strong ties to Italian firms investigated by the office she would go on to head. Kroes later said she did not reveal this work because she considered it to have been "one-off advice for a specific project".

Member states nominate their own choice of commissioner, but did President Barroso really need to give Kroes the competition portfolio, aware of what was then known about her long list of recent financial interests with big corporations, let alone the latest revelations in connection with Lockheed Martin? Barroso could have taken a principled stand and given her a portfolio without strong corporate links: DG Translation comes to mind. Instead, a Commission spokesperson at the time claimed that "the challenge of dealing with her conflicts of interest [was] a small price to pay for getting her business experience” - a statement that is highly revealing of the Commission's complaisant approach to such matters.

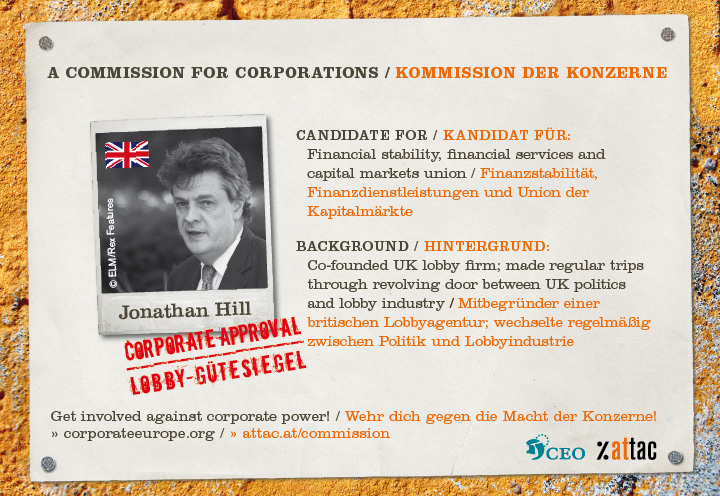

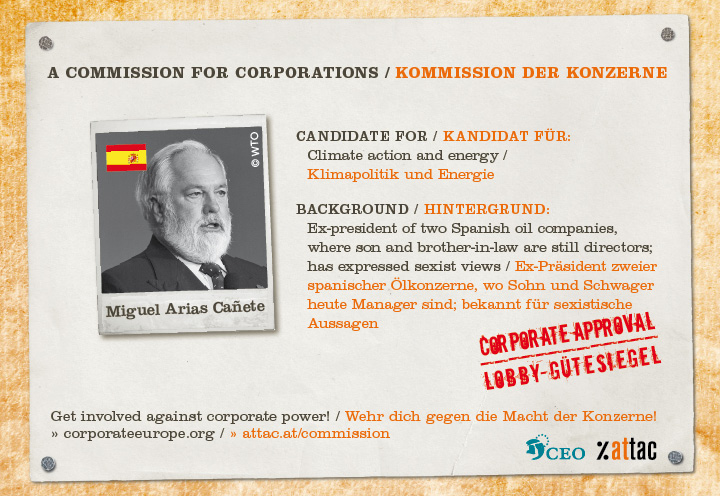

And what was the Dutch government thinking when nominating Kroes for the Commission post in the first place? The Lisbon Treaty requires Commission members “whose independence is beyond doubt”. But far too many member states have continued to appoint commissioners with corporate links. In 2014 the candidacies of now commissioners Miguel Arias Cañete and Jonathan Hill were dominating the headlines in this context.

Jonathan Hill, who eventually became financial services commissioner had had no fewer than four spins through the revolving door between UK government and politics (always for Conservative party governments) and the lobby/ PR industry. He co-founded Quiller Consultants in 1998 after stints at Bell Pottinger Communications and Lowe Bell Communications, firms lobbying on behalf of clients. Quiller was taken over by Huntsworth in 2006, a PR firm that also owns major EU-lobby player Grayling and UK firm Citigate. At his approval hearing in 2014 Hill refused to provide “a complete list of the financial services clients [he] personally, or the companies in which [he] held directorships or shares, worked for”, stating that such a list was in his possession.

And Miguel Arias Cañete, who was nominated as climate change commissioner, was the president from 2005 to 2011 of two oil companies, Petrologis and Petroleos Ducar, funded by his wife’s family. (In 2016, Cañete’s wife was named in the leaked Panama Papers.) Cañete sold his shares in the oil firms in 2014 after being nominated commissioner, but his brother-in-law Miguel Domecq Solís Beaumont remains President. Nearly 600,000 citizens signed a petition at the time to say that Cañete should not be approved by MEPs, demonstrating an unprecedented level of public interest in the commissioner hearings.

Cañete came close to being blocked by MEPs, while Hill had to make a second appearance before MEPs to gain their support, but in the end, their nominations passed and they were appointed to the Commission. It was a seriously flawed judgement on the part of incoming President Juncker to appoint Cañete to climate action and Hill to the finance portfolio, reflecting a foolhardy attitude towards the risk of corporate capture of the Commission. To tackle this, there should be a clear requirement on presidents to not appoint incoming commissioners to portfolios where they have had a financial interest in the past five years. If an appropriate portfolio cannot be found for a candidate commissioner, that should be raised with the member state. Such a rule might be an incentive to member states to nominate more appropriate candidates.

And is it not time for member states to be far more aware of the risk of corporate capture when nominating new commissioners? How about a ban on those who have professionally lobbied EU institutions in the past five years, and a ban on those with financial interests in EU level lobbying in the past five years? The Code of Conduct remains silent on these issues but such rules would give practical effect to the Treaty requirement for all commissioners to be “independent beyond doubt”. We should have this important discussion now, while there is time to get new rules in place before the next Commission sets up shop in 2019.

Green MEP Pascal Durand is currently looking at the European parliament’s scrutiny of incoming commissioners in a report for the Legal affairs committee and he makes some useful recommendations. For CEO, commissioners’ declarations of interest should definitely include:

- Specification of any professional EU lobby activities in past 10 years

- Specification of any financial interests in EU lobbying in past 10 years

- Details of all professional activities and financial interests of spouses and partners in past 10 years, alongside those of other family members where there is a financial or professional link

- A review of the declaration each year, including the risk of conflicts of interest

- Additionally, if a file is allocated to another commissioner or other measures are put in place, because of the risk of a conflict of interest, these should be made public and there should be MEP scrutiny of the proposed arrangements. For example, special arrangements were put in place regarding Cañete, but we are not aware of any external oversight.

Kroes’ exit from the Commission

So far we have just discussed Kroes’ arrival in the Commission; her departure has created just as many waves.

After Kroes’ authorisation hearing in the European Parliament in 2004, the Wall Street Journal reported that “Kroes also promised to never engage in business activities once her five-year commission term ends in 2009, when she will be 68.” Now her lawyer has said:

“It is true that Mrs Kroes made this pledge at the beginning of her first term with the European commission. Having fulfilled this term, Mrs Kroes fulfilled this pledge and did not enter into business activity. Instead, she was honoured with a second term in a completely different field. Having now finished her second term, she no longer feels bound by the commitment made prior to taking her first post.”

Kroes has certainly blown that promise out of the water.

In the months after the Barroso II Commission left office, Kroes became a paid, special adviser to Bank of America Merrill Lynch. BoAML is a major EU lobbyist, recently increasing its declared spend on lobbying from under €50,000 in 2013 to €1,250,000€ - €1,499,999 in 2015, and has had at least 11 high-level meetings with the Commission since December 2014. Like other banks, Merrill Lynch was heavily involved in sub-prime mortgages in the US, which ultimately contributed to the 2007-08 financial crisis. Merrill Lynch was later sold to Bank of America which was subsequently bailed out by taxpayers.

Describing her role at BoAML, Kroes told the Commission:

“Via sharing experiences, insights and exchanging perspectives, the Bank aims to strengthen its client engagement and relationships. More concretely for my role as an advisor, this means I could be requested to contribute to conferences and engaging politicians and thought leaders."

But she does not appear to have been asked to clarify what “engaging politicians and thought leaders” means in practice which seems odd as the code of conduct bans ex-commissioners from some lobbying activities for 18 months.

And of course more recently, once the revolving door regulations on ex-Barroso II commissioners had ended on 30 April 2016, Kroes joined the public policy advisory board of Uber and the board of directors of Salesforce. Both are paid roles and both corporations are major players in the tech world; both are high-spending active EU lobbyists; and it is not hard to comprehend why either firm would wish to recruit the services of the former Digital agenda commissioner. Specifically, Salesforce has more than doubled its EU lobby spending to €700,000+ in the past year, while Uber has had 16 lobby meetings with senior Commission officials since December 2014. Both companies clearly have an agenda to promote to the EU institutions, especially at a time when digital matters are centre-stage for the Commission.

As Digital agenda commissioner, Kroes was vocal in her support for Uber. In a blog, hosted by the European Commission and published in Kroes' name in April 2014, just two years ago, Kroes wrote: "I am outraged at the decision today by a Brussels court to ban Uber, the taxi-service app." She went on:

"I’ve met the founders and investors in Uber. My staff have used the service around the world to stay safe and save taxpayers money. Uber is 100% welcome in Brussels and everywhere else as far as I am concerned.”

She even announced via Twitter that she wanted to "start a new # tag ... #UberIsWelcome in Brussels and everywhere."

It is a testament to the weakness of the code of conduct that by accepting these roles, Kroes has not been found to have broken any rules. The BoAML role was authorised by the Commission and the Uber and Salesforce roles, coming 18 months after she left office, did not require any authorisation.

Yet, arguably the latter two are a breach of a former commissioner’s treaty obligation to act with integrity and discretion and require some action by the Commission. The Commission should have taken action on these cases when they first came to light but has not done so, and a Commission spokesperson recently indicated that this was because there had not been public outrage about Kroes’ move to Uber, an apt demonstration of the Commission’s lack of proactivity when it comes to commissioners and ethics. ALTER-EU has made a formal complaint on this issue earlier this week.

Commissioners’ ethics require independent oversight

The conclusion from the ethics scandals that have surrounded the Commission in recent years - Kroes, Barroso, De Gucht, Cañete, Hill and others - seems pretty obvious. The Commission cannot be left responsible for its own ethics. Colleagues in the form of today’s College, should not be in the position of adjudicating on the ethics of their recent predecessors, let alone their immediate colleagues. Juncker recently described Barroso as a “friend”; no wonder it took him two months to take any steps on Barroso’s ill-judged move to Goldman Sachs International.

We need to scrap the current Ad hoc Ethical Committee and instead have a fully independent body to take care of all ethics matters relating to commissioners. This should be a permanent, professional, transparent and fully independent ethics body which would be entirely responsible for all matters relating to incoming, current and former commissioners’ ethics, with investigatory powers and the authority to sanction rule-breaking or other misconduct.

The Commission is too complaisant about conflicts of interest and too relaxed about the risk of corporate capture. Change is long overdue.