European Central Bank has bought more climate-trashing bonds

Pressure has been mounting on the European Central Bank over its purchases of certain corporate bonds, but new research shows no change. In its mission to stimulate the economy, it is still purchasing climate-harming bonds.

At a press conference on 8. June, Mario Draghi continued to refuse disclosing the amount the ECB spends on bonds from specific companies. But pressure is mounting. Photo: European Central Bank

Despite the serious concerns raised by a broad political spectrum in the European Parliament and from 76 NGO’s, the European Central Bank sticks to its guns. There is to be no significant transparency about its purchases of corporate bonds, and certainly no change in its approach to selection of investments. Updated information about the holdings of the ECB show no hesitation in supporting fossil fuels. Despite the obvious clash with the EU’s obligations on climate change, transparency and accountability in the bond purchasing programme remain absent.

Stimulating fossil fuels

In December 2016, Corporate Europe Observatory broke the story on the European Central Bank’s purchases of corporate bonds under its quantitative easing scheme – a programme set up to stimulate the European economy. The data uncovered by translating the published codes ('ISIN' codes) to the actual names of the bond issuing companies, showed a marked preference for companies that contribute to climate change, including oil companies, car makers, motorways, and energy companies.

Seeing the scarce information in the public domain, this case has now become an issue between the European Parliament and the ECB. Forty-one MEPs from all political groups have signed a letter demanding transparency about selection criteria and the disclosure of the sums the ECB has so far spent on bonds of individual corporations.

But so far, the ECB does not seem to have budged an inch. This has been made clear by the ECB’s top executive, President Mario Draghi, at encounters with parliamentarians. Now new statistics over the Bank’s investment back this up, revealing that over a third of bond purchases are tied to some of the biggest climate-harming companies.

Indefensible opacity

From the outset when the programme was initiated in June 2016, the ECB has been shy about publicising its purchases, referring to an alleged danger of manipulating markets. For that reason, the Bank has refused to reveal much information on how the bonds are selected, except for headlines on investment grade, and that they cannot be public entities or financial corporations. Perhaps more importantly, the ECB has denied the public any knowledge about the actual amounts spent on individual bonds, citing the danger of sending signals that could distort the market. Yet this excuse for their lack of transparency makes no sense. It has been clear from very early on that advanced investors and analysts could easily discern the details of the ECB’s purchases, and were even able to produce statistics on the effects of the ECB intervention on the companies which have been favoured by the Bank and those which have not. In the course of only two months, discrepancies were in the area of 10 percent, according to esearch done by Citi Research, shown in a graph published by - among others - Financial Times in its FT Aplphaville blog.

It seems the ECB is about to publish more information about the bonds, namely "issuer, maturity and coupon rate". In fact, these data are easy to find to anyone who knows the ISIN code of a bond, the codes already available via the ECB's website. It does save researchers some time, but it is not a genuine increase of transparency.

The clients of the ECB

But with amounts undisclosed, only a rough picture of the ECB’s shopping spree can be established outside the financial community, with statistics only on what bonds have been bought, not the amounts spent.

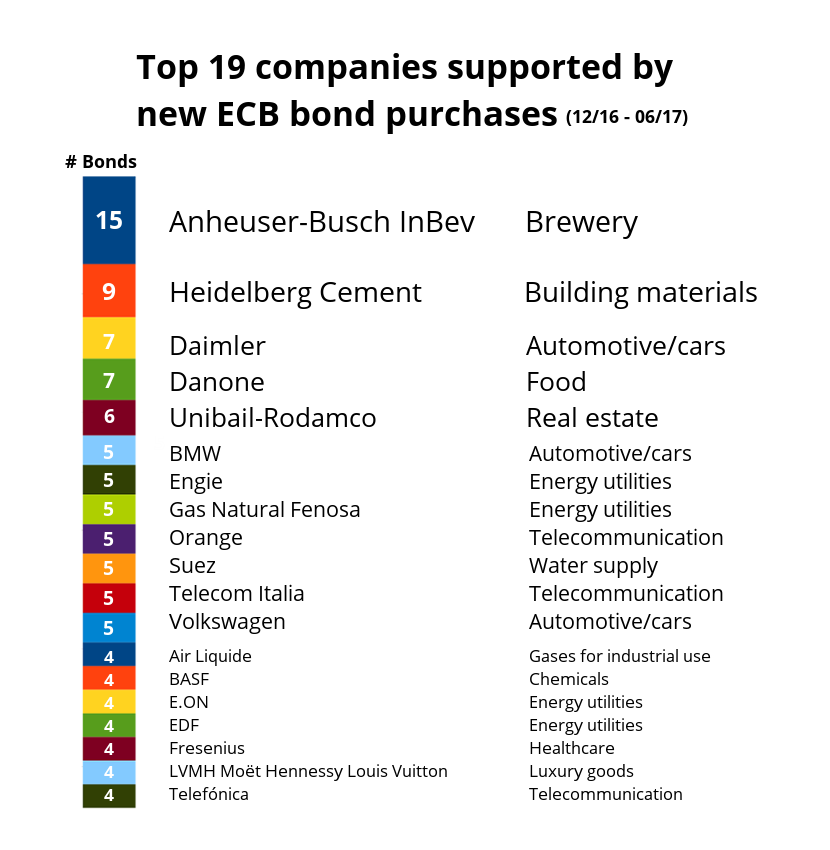

Going through the purchases made since Corporate Europe Observatory published its first analysis of the bonds in December 2016, produces an interesting picture. Remarkably, the two companies topping the list are Anheuser-Busch and Heidelberg Cement, a brewery and a building materials producer, both known to be acquiring new companies recently. Some analysts indicate that mergers and acquisitions do indeed affect the interest of the ECB in a specific company. But the most astonishing feature of the lists remains the companies linked closely to fossil fuels one way or the other.

The list of companies that have benefitted from at least three purchases, still includes three car makers (BMW, Daimler, and Volkswagen), two oil companies (Repsol, and ENI), two motorway companies (Atlantia, and Autoroutes du Sud de la France), and ten energy utility companies – companies that are involved in the whole fossil fuel supply chain, from the extraction of coal and gas, through to its burning for electricity or being delivered to customers. The same companies who have been aggressively lobbying to weaken climate action and stop the move away from polluting fossil fuels towards renewable energy from the sun, wind, and water.

The picture becomes clearer when the purchases of individual national central banks is brought in. In Spain and Italy, in particular, the number of new bond purchases directly linked to fossil fuels are staggering. In the case of Italy, 23 of 30 new bonds are from either oil, gas, electricity, or motorway. In the Spanish case, 16 of 29 belong to the same categories. As for the German Bundesbank, which bought 45 new kinds of bonds, 8 were from energy companies, a sector coming second only to the clear winner in Germany: car makers, with 17 different bonds.

Put together, carmakers, oil and gas companies, energy companies and motorways, make up 107 of the 271 different bonds bought since early December 2016. The total current holdings show BMW and Telefónica on top (with 20 different bonds). In the top 20 of beneficiaries, energy companies top the list with 81 different bonds, cars come second with 50, telecommunications come third, and oil and gas companies fourth with 31.

Clearly investments that are relevant to the EU effort against climate change, and as they are simply cheap money. The risk of that money strengthening and locking in a fossil fuel-based economy is considerable, and reinforces the already damaging approach from the European Commission and national governments that promotes more gas infrastructure, despite signing a global agreement to keep temperature rises “well below 2 degrees” and move away from fossil fuels.

Keep knocking on doors

But as mentioned, these data suffer from a serious weakness: while the type of bonds bought can be deciphered from the ISIN codes available on the ECB’s website, the ECB has no intention of divulging the sums spent on each bonds.

Several parliamentary questions have been asked, both in the European Parliament and in national parliaments, about the purchases of the ECB, but when it comes to the crucial numbers, the door is shut in the face of MPs. For example when German political party Die Linke asked about the bond purchases, it was told, “such an overview is not in the possession of the government”. And when asked about the opinion of the European Commission on the corporate bond purchases, the German government replied that “the Commission respects the independence of the ECB, as does the government”. In other words, the German government is not inclined to even discuss the characteristics of the bond purchases.

Well-oiled corporations and public investments

It does make sense to invest public money in response to the crisis, but the drawbacks of the EU model seem clear. Going merely for “well-oiled corporations” leaves out job-intensive small and medium enterprises. It also helps exacerbate climate change, saving us from one crisis by fuelling another, when it could be boosting renewable energy with the same money. And while the ECB claims investments are decided on the basis of neutral criteria such as investment grade (assessment of the viability and security of an investment), this does entail a political choice. A political choice that does not seem to be affected by the opinions in elected assemblies across the EU.

Comments

The world is going down under climate change and global warming and the financial institutions are doing NOTHING!

https://www.ecb.europa.eu/pub/economic-bulletin/focus/2018/html/ecb.ebb…

ECB's green washing approach.

The aim of central banking is to foster growth. The goal is around 3% per anum. This implies an increase in energy consumption of 100% every 30 to 40 years.