Hidden contracts? Corporate lobby spending in EU member states in the spotlight

Undeclared multi-million contract between FleishmanHillard and Monsanto leads to stricter approach from the EU Transparency Register

It is a public secret that the amounts of lobby spending as declared by corporations and lobby groups in the EU Transparency Register often present vast under-estimates of the real figures. A case in point was the dubious lobby campaign by lobby firm FleishmanHillard carried out for Monsanto, aimed at safeguarding the re-authorisation of controversial pesticide glyphosate. This job, as we previously reported, involved a €14.5 million contract, tenfold the amount either corporation had officially declared.

Corporate Europe Observatory filed complaints to the Register regarding the inaccurate, low-ball lobby spending figures declared by both Monsanto and its lobby firm FleishmanHillard. In response the Register’s secretariat has now announced it will present new guidelines to make sure registrants will include their lobbying spending at national level if it concerns EU policy-making. This should generate a far more realistic picture of corporate lobby spending in the EU.

‘Fichier Monsanto’

This is how the story began: revelations in French media showed that during 2016 and 2017, Monsanto had hired FleishmanHillard to compile a vast list of Monsanto’s opponents (the ‘stakeholder lists’), which was seen as potentially illegal in France. The list of critics was comprehensive, containing the names of some 200 people in France, including journalists and politicians such as the French Environment Minister at the time, Ségolène Royal.

Numerous official complaints were subsequently submitted to the French authorities. But as soon became clear, the campaign extended to various other EU countries, as well as the Brussels level itself. In the meantime agrichemical giant Bayer had acquired Monsanto, and in the wake of the scandal quickly ditched FleishmanHillard, and hired law firm Sidley Austin to do an investigation and clean up the mess.

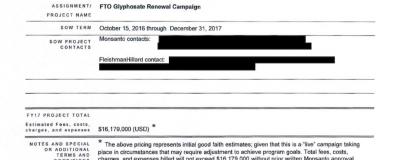

On 5 September 2019 Bayer published Sidley Austin’s report. While the report claimed nothing illegal had been done, importantly it disclosed the precise details of the contract between FleishmanHillard and Monsanto, including the work plan and the overall value of the contract. Monsanto had paid FleishmanHillard no less than €14.5 million to help steer the glyphosate debate in Brussels and in various member states. The contract ran between 15 October 2016 and 31 December 2017. SidenoteThis strikingly large figure was also mentioned by Monsanto’s (now Bayer’s) Sam Murphey in a video-taped deposition, published by the organisation US Right To Know (USRTK). Murphey disclosed this information to a US District Court in the context of one of the over 18,400 claims against Monsanto from cancer victims.

Image from Sidley Austin report via www.bayer.com

This figure of €14.5 million is in stark contrast to both companies’ entries to the EU Lobbying Transparency Register. FleishmanHillard stated it was paid up to €800,000 in 2016 by Monsanto, and up to €600,000 in 2017, its top client for those years. Monsanto for its part claimed its total lobbying budget to be at most €1.45 million between September 2016 and August 2017.

According to the contract, the expected work to be done by FleishmanHillard included the controversial ‘stakeholder lists’, listing no less than 1,475 individuals across several European countries, developing campaign messaging and narratives, delivering research briefs “to deliver credible economic and social impact assessments in each country”, media monitoring and setting up “grassroots” groups by helping “recruits”, notably farmers, to push industry’s pro-glyphosate messages to decision makers. SidenoteFor this particular item, Monsanto had also hired lobby firm Red Flag. This company ran Monsanto’s ‘Freedom to Farm’ campaign, organising stands at agricultural shows across Europe which recruited farmers to help lobby for glyphosate. Red Flag was set up by a former partner of lobby firm Hume Brophy, which coordinates the Monsanto-led Glyphosate Task Force (GTF). The GTF was in charge of filing glyphosate’s renewal dossier with the EU authorities.Monsanto was to be given constant updates and ongoing strategic counsel. All in all, no less than 59 for-hire lobbyists were involved, either employed by FleishmanHillard or by subcontractors at national level.

Complaint to Transparency Register

Corporate Europe Observatory submitted a complaint to the Register’s secretariat, pointing out that the figures both companies declared are at such discrepancy with the amount of €14.5 million of the FleishmanHillard-Monsanto contract, that this can be regarded as a clear case of misinformation. There was no doubt that the sum of €14.5 million should have been declared, because the scope of the Register covers all lobbying activities “carried out with the objective of directly or indirectly influencing the formulation or implementation of policy and the decision-making processes of the EU institutions, irrespective of where they are undertaken and of the channel or medium of communication used”. (emphasis added)

The glyphosate re-authorisation was an EU decision, with a final vote by EU member states. FleishmanHillard’s work targeted key decision makers in Brussels and in various member states. Therefore FleishmanHillard’s activities for Monsanto regarding glyphosate all fell within the remit of the EU Transparency Register. The costs involved should have been declared by both parties in their entries. This would have given the public and decision-makers a more realistic picture of the lobbying firepower of the pesticide industry.

In our complaint we stated that “the size of the discrepancy between the lobby expenditure figures presented by FleishmanHillard and Monsanto on the one hand, and the value of the lobbying contract between the two on the other, excludes the possibility of a mere factual error”, and concluded that both firms should be excluded from the Register. This would mean that they would lose access to high level officials and Members of the European Parliament.

The Transparency Secretariat responded to Corporate Europe Observatory, declaring that it would “update its guidelines for registrants with regard to activities carried out at EU Member State level. In doing so, whilst recognising the complexity of the matter, we hope to ensure a consistent interpretation of the scope of activities covered in future.” The Secretariat concluded it could not take further action on the case itself since the figures for these years no longer feature on its website and Monsanto is no longer registered as an independent entity. SidenoteHistorical data from the EU Transparency Register can be easily accessed via www.lobbyfacts.eu[/sidenote]

The consequence of the Secretariat's decision ought to be that lobby spending figures declared by corporate lobbies across all sectors will feature far higher and more realistic figures, now that the Register will pay more attention to spending on member state level lobbying. Whether they will actually do this, and how the new guidelines will be implemented, remains to be seen.

Solve the Transparency Register pitfalls; end privileged access for industry

While the Secretariat’s decision is a step forward, the fact that such massive under-declaration was able to go under the radar for so long is indicative of the Transparency Register’s structural problems – from the lack of checks on the quality of data, to the scant resources and powers of the Secretariat, to the stark absence of lobbying activities at the Council of the EU, that prevent it from effective functioning. In November 2017 Corporate Europe Observatory had already caught Monsanto under-declaring their lobby budget by one million euros, yet the company faced no thorough checks nor were they sanctioned as a result.

Negotiations to reform the EU Register have been ongoing since 2016, without results thus far. Now, we expect the EU Commission, Parliament and Council to pick them up again but it is unclear what sort of progress we might see.

Clearly, transparency in lobby spending, lobby meetings, etc is not an end in itself. It is one important tool for citizens to exercise their right to know who tries to influence political decisions on a structural basis, and with what aim – particularly those who have most commercial interest, and most resources to spend. Realistic figures of lobbying spending are important, but provide only one indicator of that power brokering.

What really counts is effective regulations, and a change of culture that stops public institutions from giving privileged access to big corporations. In some cases, such as lobbying by the fossil fuel and tobacco industries, this should be tackled by cutting off their access to private meetings as much as possible.

This is needed at all levels, including member states. For instance, in a similar way to the battle over glyphosate, national governments will be heavily targeted by industry lobbying following the announced pesticide reduction targets, laid down in the Commission’s Farm to Fork Strategy. An upcoming report by Corporate Europe Observatory and LobbyControl provides a variety of other examples of corporate lobbying targeting the German Government, which holds the EU Presidency over the second half of 2020.

While it is unclear when the new guidelines will take effect, in a year’s time we should be able to see whether corporate lobby groups live up to them. “Transparency is our license to operate” may nowadays be their mantra, yet they still prefer to keep the real figures hidden.