EU Defence Agency under pressure to change rules after Airbus revolving doors scandal

Update 21 July 2021: The European Ombudsman concluded on 15 July that the European Defence Agency (EDA) should have forbidden its former Chief Executive from becoming a Strategic Advisor for Airbus Defence and Space.

Like CEO, Vredesactie and ENAAT, the Ombudsman has found that the risks of conflicts of interest were too high and could not be mitigated. The only way to handle them was to prohibit this job. For the Ombudsman, failing to do so constituted maladministration.

The Ombudsman also concluded the Agency’s assessment of conflicts of interest in Domecq’s new roles at Airbus was not thorough and the conditions put in place to mitigate conflicts of interest were insufficient. Worse, as the Agency itself admitted, these conditions could not be monitored or enforced.

The EDA must now take the Ombudsman’s ruling into account and change its internal procedures and rules. It also needs to develop its understanding of the risks created by revolving doors. Only by doing so, will we prevent such a case from happening again.

This ruling also adds weight to the evidence that EU’s approach to the risks created by revolving doors moves is inadequate. Examples from EU Commission officials & EU Commissioners, but also independent agencies like the European Banking Authority and the European Investment Bank, show that there is an excessive reliance on limitations put on employment that are not monitored or enforced.

This is not a credible way to handle conflicts of interest.

“The Ombudsman is concerned about the potential risk of conflicts of interest.” These concerns led the European Ombudsman’s office to launch an inquiry into the European Defence Agency’s handling of the request by its former Chief Executive to allow him to become a lobbyist for Airbus.

The move had already caught the attention of journalists and campaigners. Corporate Europe Observatory, peace group Vredesactie and the European Network Against the Arms Trade (ENAAT) have been trying to understand how the job got approved. What we found was a lax process that did not adequately protect the European Defence Agency’s (EDA) independence and integrity.

Approving the former head of the EDA to become a lobbyist for one of the world’s biggest arms companies is simply a bad decision. It allows a company that actively lobbies the EU’s defence agency, and earns contracts from its public procurement, to benefit from insider access, know-how and influence. It is also another alarming precedent showing that the current approach to the revolving doors problem is not working.

Last week, at the same time as it was reported that the Ombudsman was to undertake a wide-ranging investigation into the issue of revolving doors by former Commission staff, her office also published the response from the EDA to its inquiry. The EDA still defends its decision regarding its recently departed Chief Executive but, under scrutiny of the Ombudsman, it finally seems open to improving the rules.

From EDA Chief Executive to Airbus lobbyist

After a five-year mandate overseeing the European Defence Agency, Jorge Domecq’s last working day came on 31 January 2020.

Domecq had been the Agency’s most senior official, responding directly to the Steering Board made up of EU Defence Ministers and the Council. His responsibilities included overseeing the EDA’s strategy and planning, and its relationships with member states, EU institutions and other third parties.

On 28 July, just six months after leaving the EDA, Domecq informed the agency that he wished to start working as Head of Public Affairs and Strategic Advisor for Airbus Defence and Space. His application for approval of this position was sparse, but one detail in particular set off alarm bells: the intended start date was just two weeks later (16 August 2020).

“Just received. Airbus. Starting mid-August. Advice required asap.”

What followed was a bumpy assessment, with poor cooperation from Domecq, a breach of the EDA’s Code of the Good Administrative Behaviour and, ultimately, an inefficient outcome.

Domecq’s original application was so sparse that it did not enable the agency to assess its risk. The EDA immediately reverted to Domecq requesting further information. The former Chief Executive replied that he would ask his “employer”, and that it was likely that the information would not be available before the job’s starting date.

On 27 August 2020, the Spanish press publicly announced Domecq’s new job – in spite of the fact that it had not yet been authorised by the EDA, as per the ethics rules. The next day, on 28 August, almost one month after Domecq had promised to provide further information, the EDA sent another reminder. Domecq finally provided this information on 31 August.

By this point he had already been on the payroll of Airbus for two weeks.

The EDA then started its assessment. Through this process it found potential conflicts between Domecq’s new employment and the legitimate interests of the EDA. It also found that Domecq had broken the Agency’s ethics rules (rules he had previously been in charge of enforcing) by taking this job before receiving authorisation.

Domecq’s new corporate job was nevertheless approved on 7 September 2020 by High Representative Josep Borrell, acting as the Head of the European Defence Agency. Sidenote As Domecq had held the most senior position at the EDA only the Head of Agency could act as the Authority Authorised to Conclude Contracts (AACC).

As has become customary with the EU’s revolving door issue, the job was approved with some limitations – limitations that no one actually monitors and that lack enforcement power.

By the time the job was authorised by his former employer, Domecq had been in place at Airbus for almost one month.

Airbus, the European defence giant

To understand the gravity of this case it is crucial to examine the overlaps between the European Defence Agency and Airbus.

The EDA acts as a linking point between the EU institutions, 26 member states Sidenote Denmark opted out and the defence industry. Its goal is to coordinate national investment in defence capabilities, including stimulating “defence Research and Technology (R&T) and strengthening the European defence industry”.

Airbus, often associated with its manufacture of commercial airplanes, is also one of the world’s biggest defence companies. Among its product portfolio are military fighter aircraft, military helicopters, missiles and defence systems, among others.

The company is infamous for the sale of weapons to both countries at war, and dictatorial regimes. Recent controversy has focused on the sale of Eurofighter Typhoons to the Saudi Air Force, which is using them to bomb Yemen, in breach of international humanitarian law.

The company is also a market leader in the sale of equipment for border security and has actively lobbied the EU to pursue a more militarized response to migration, often with very detrimental effects on the rights of migrants and refugees.

In recent years, Airbus has been plagued by scandals, as the company was involved in a string of corruption cases in more than twenty countries across the globe. In 2020 the company paid a staggering €3.6 billion to settle charges, after a four-year investigation by French, British and US authorities into corruption. According to French prosecutors, the company had increased its profits by one billion euros as a result of bribery. A British judge stated that bribery was endemic within Airbus in core business areas.

Airbus lobbied the EDA from the very start

In spite of this dubious record, the company is intrinsically linked with both European governments and the EU itself. It is, for instance, the biggest corporate recipient of EU security funding. Spanning contracts between 2009 and 2023, the Airbus group has been involved in 50 EU funded projects, raking in over €37 million. Sidenote Data extracted from Open Security Data Europe, a database that compiles information from the Internal Security Fund (2014-20), which provided funding to implement EU policing and border policies, as well as projects by EU member states; the security component of Horizon 2020 (2014-20), the EU’s research and innovation program; and the predecessor to Horizon 2020, the Seventh Framework Program for Research and Development (FP7, 2007-13). https://opensecuritydata.eu/about Airbus also has direct financial links with the European Defence Agency. In May 2020, for instance, the EDA renewed its framework contract with Airbus to provide satellite communications, an ongoing contract since 2012 that, “is estimated to be worth tens of millions of euros” according to Airbus.

In 2020 the company paid a staggering €3.6 billion to settle charges, after a four-year investigation by French, British and US authorities into corruption.

Unsurprisingly, Airbus has found it easy to gain lobbying access. With a declared lobby budget of at least €1.75 million in 2019, and at least three lobby consultancies working for it Sidenote BusinessBridgeEurope, G Plus/ Portland, Avisa Partners as per lobbyfacts.eu checked 13 April 2021 , the company has scored over 200 meetings with the upper echelons of the EU Commission since November 2014. It is the company with the second highest Commission access, with only Google securing more meetings.

When it comes to the EDA, Airbus’ lobbying is arguably inseparable from the agency itself. At the European Agenda Summit in 2008, an EU lobbyist for the company (then called EADS) bragged that the EDA was the company’s baby as “the agency was 95% similar to EADS’ proposals”. A book produced by the EDA to celebrate its tenth anniversary explains how this happened:

“In 2002, we organised a dinner that gathered more than 200 representatives from national parliaments and from the Convention”, Troubetzkoy [Airbus’ lobbyist] points out. “I personally asked Valéry Giscard d’Estaing to consider, after the failure of the EDC in 1954, a new political impetus for defence cooperation in Europe through the creation of a dedicated Agency. He told me he would take up the challenge.”

Jorge Domecq: from lobbied to lobbyist

It would have been impossible for Domecq to have avoided Airbus during his five year tenure as Chief Executive of the EDA. In his authorisation request to his former employer seeking permission to take up the new corporate job, Domecq stated that he:

“met and discussed with Airbus senior management strategy, policy and projects relevant to the European Defence. I never discussed or entertained any discussion related to specific call for proposals or bids in the EU context in which Airbus had or could have a direct interest in. Furthermore, each time I met any company representatives I made sure that these matters would not be discussed. You can check the minutes of these meetings to verify this aspect. “

When journalist Peter Teffer requested access to these documents, however, the EDA rejected his application. The agency argued that disclosure could affect the protection of “defence and military matters” and Airbus’ commercial interests.

A separate access to documents request made by Vredesactie, and the Ombudsman’s ongoing inquiry, can now at least provide us with a glimpse into the interactions between Domecq and Airbus during his mandate at the EDA.

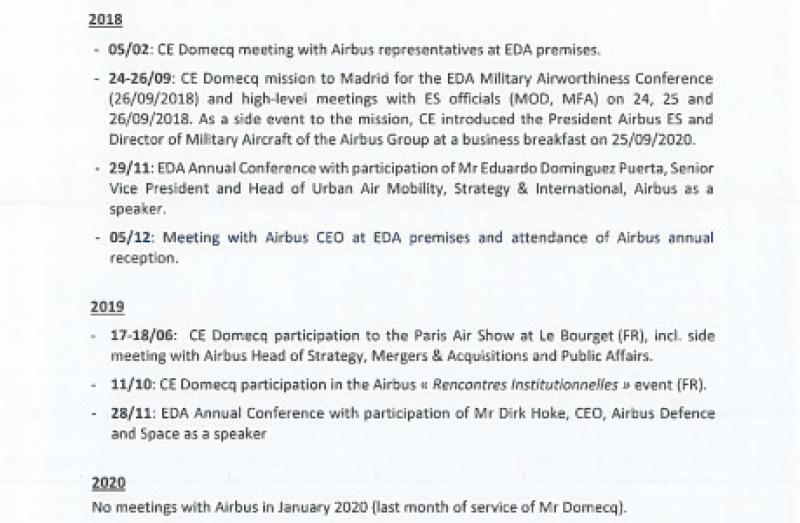

In 2018 and 2019, Domecq met Airbus seven times in a variety of settings - at the sidelines of an official mission to Spain, conferences, Airbus’ own annual reception, the Paris Air Show, and, of course, in bilateral lobby meetings.

Domecq met with the Chief Executive of the Airbus Group, the Chief Executive of Airbus Defence and Space, the President of Airbus Spain, and a variety of representatives of different departments of the Airbus Group.

The documents received show, for instance, that Guillaume Faury, the Chief Executive of Airbus, personally invited Domecq to participate in an exchange of ideas with himself and various representatives of other company departments, including Dirk Hoke, the Chief Executive of Airbus Defence and Space. Hoke was to lead an exchange on “Major European defence programs”.

In his new job at Airbus, Domecq is directly advising Hoke.

In Domecq’s authorisation request to the EDA, he declared that he would not be responsible for lobbying EU institutions and bodies as this area of work is “the sole responsability [sic] of the Public Affairs office of Airbus in Brussels”.

However, this list of meetings that Domecq himself held as Chief Executive of the EDA with representatives of various Airbus offices tells a different story.

Airbus’ direct and indirect lobbying

As is standard procedure for any EU senior official, upon leaving public office Domecq remained bound by a two year notification period during which he was required to seek authorisation from his former employer before taking up any new job. It is the responsibility of the official to notify its former employer before taking up a new job, to allow them to assess the role for potential conflicts of interest and lobbying implications. This prior notification is fundamental because, if the employer finds reason for concern, it can impose restrictions, or even instruct the former staff member not to take up the job offer Sidenote Like most agencies, the EDA has implemented its own Staff Regulations, which are based on the EU Staff Regulations https://eda.europa.eu/docs/default-source/documents/eda-staff-regulations.pdf .

Domecq’s application to the EDA, released to us under access to documents laws, explained after some prodding, that at Airbus he would be responsible for the company’s lobbying, including on core activities such as proposing country specific lobby plans on “hot topics”, interacting with and trying to impact “political counterparts” and coordinating lobby campaigns.

Domecq did not see the fact that he was to become a lobbyist as a problem, because he stated his lobbying would be limited to Spain. However, Spain is itself a member of the EDA, and member-states have direct involvement in the running of the agency. The EDA, as it says itself, is the “only EU Agency whose Steering Board meets at ministerial level”. This means that Defence Ministers “decide on the annual budget, the three year work programme, the annual work plan, projects, programmes and new initiatives.”

There was also a second component to Domecq’s job. As the EDA puts it, at Airbus Domecq would, in effect, be wearing “two hats”. The second one involved the role of Strategy Advisor to the Chief Executive of Airbus Defence and Space, Dirk Hoke. The same person that had been in contact with (and lobbied) Domecq while he was leading the EDA.

Now, as an advisor to Hoke, Domecq would contribute his “experience” to Airbus’ global strategy “worldwide as well as NATO, EU or individual countries in Europe or beyond”. This part of his job makes him responsible for work on the “policy domain” and might include “occasional contacts with senior representatives of other countries and organisations (including EU) beyond Spain”.

The former EDA chief argued that this would not include lobbying activities towards the EU institutions or bodies.

It is hard to reconcile this interpretation with the information that preceded it. An important component of lobbying is what is often called “indirect lobbying” meaning providing advise on who and how to influence decision-makers often based on information gathered either by their professional experience or by continued contact with decision-makers As the EU Ombudsman explained when closing the inquiry into former President Barroso’s new job at Goldman Sachs International, “one of key objectives of a lobbyist is to meet with public officials and to obtain from them information which may be useful to the company they represent.“

Even if Domecq does not directly try to influence his former EDA colleagues, if he advises others on how and who to lobby on EDA issues (ie most of the EU’s defence cooperation and investment), then he is in effect performing indirect lobbying activities.

Conflicts of interest identified by EDA

After reviewing Domecq’s application and consulting with the EDA Staff Committee, the EDA found that there was a concrete overlap between Domecq’s new job and his past as Chief Executive, not only on the area of activity, but also “in terms of the actual duties which Mr Domecq would perform, advising and engaging with senior members of the public and private defence sector.”

Yet, the agency said that it did not have the evidence to establish a conflict of interest, only that this situation could “de facto lead to such a conflict”. This was the main reason given for excluding the possibility of refusing to assent to Domecq’s new job.

That is simply not good enough. The inherent risk of conflicts of interest in Domecq’s new corporate role, the immense overlap of functions and responsibilities between the two jobs, the fact his job explicitly includes lobbying – even if indirectly – on EU defence policies and his seniority level were enough grounds to reject the job. This would have been the only adequate way to prevent and avoid damage being done to the EU institutions, and to limit the benefit that Airbus stood to gain.

Instead, the agency authorised the job, implementing conditions to mitigate the risks. It decided that its former Chief Executive:

-

should not have contact with EDA staff for the purpose of lobbying or advocacy on matters for which he was responsible as Chief Executive of the EDA (until 31/01/2021);

-

should remove himself from any Airbus decision or task which concerns EDA activities in order to avoid any perceived or real conflict of interests (until 31/01/2022);

-

should abstain from contact with the Airbus Brussels office on matters which concern the EDA (31/01/2022).

As has become standard in EU revolving doors cases, no monitoring or enforcement mechanism existed or was put in place to ensure adherence to these conditions. The EDA has just admitted this much to the Ombudsman:

“It is important to note that EDA has neither the resources nor the competence to perform a systematic monitoring of post-employment conditions, beyond raising awareness and ensuring transparency on the conditions set”.

EDA’s weak approach: narrow and impossible to monitor

The EDA seems to believe that by imposing these limitations and making them public following media inquiries, it has taken sufficient steps to prevent problems arising from this move.

This is an incredibly weak approach, especially as the limitations themselves are either narrow or impossible to monitor. Take, for instance, the prohibition on lobbying his former colleagues. This condition was only set until January 2021 - ie it would cover just the first five months of his tenure at the company.

A seemingly stronger condition prohibits Domecq from contacting the Airbus Brussels office on matters which concern EDA for two years. Yet, as we have learned from the lobby documents and the EDA’ s response to the Ombudsman, the relationship between the EDA and the arms company is not at all limited to contact with the Brussels office. Even the EDA’ s procurement contracts with Airbus include contact with other sections of the Airbus group.

The third restriction is stronger, yet again it is impossible to monitor or enforce. Overall, the restrictions imposed do nothing to address the fact that at the EDA, Domecq had gained insider know-how, access and influence that will directly benefit the Airbus Group. Even if Domecq does not directly contact the Airbus Brussels office, his new job makes him directly responsible for advising the Chief Executive, including on EU policy. There is also nothing stopping him from advising other departments.

Domecq met with Spanish government officials, including the Spanish Defence Minister, Margarita Robles, with whom he had previously interacted as Chief of the EDA.

There has also been no assessment of the EDA’s special position vis-a-vis national Defence Ministries and of the Chief Executive functioning as the main link to national Ministries. As an Airbus lobbyist, Domecq will come into direct contact with state representatives who not only decide on the general policy lines of the EDA, but also on specific projects, programmes and other new initiatives from which Airbus stands to benefit.

Recently, for example, Domecq met with Spanish government officials, including the Spanish Defence Minister, Margarita Robles, with whom he had previously interacted as Chief of the EDA. In this February 2021 meeting, the Spanish Prime-Minister reportedly reiterated his “commitment to military programmes tied in to European defence”.

In spite of all of this, the EDA concluded that the case, and risk of conflict of interest, was not severe enough for a rejection. Yet, there is a clear basis for it: an authorisation request from the former highest official in an agency, just months after leaving office, for a position that includes both direct and indirect lobbying for a company that is deeply linked – by lobbying and procurement - to the EDA itself.

A time-limited prohibition, would have been the only adequate way to protect the independence, legitimate interests and reputation of the EDA. It would also have been the appropriate measure to prevent a private company from unduly benefiting from a revolving door hire.

EDA Chief Executive broke Staff Regulations

The assessment by the EDA did establish one crucial fact: Domecq broke the Staff Regulations by accepting and starting his employment at Airbus before he was granted authorisation. This showed blatant disregard for the rule which the EDA’s own assessment stated it was highly unlikely Domecq did not know. Firstly, because Domecq had signed a declaration when leaving office stating that he understood this requirement; and, also, crucially, as Chief Executive of the agency he had himself been responsible for such authorisations before leaving the EDA.

By not waiting for authorisation before starting his new job, giving the EDA only two weeks notice of his employment, Domecq severely limited the options of the agency.

In response, the agency proposed to issue a mise-en-guarde, in other words, a warning that he had broken the rules – we do not, however, know whether this warning was finally issued. Even if it was, the severity and credibility of the warning is gravely undermined by the fact that it was not publicised.

Recommendations to the EDA from Corporate Europe Observatory, Vredesactie and ENAAT

-

Re-examine Domecq’s authorisation to become a lobbyist at Airbus.

-

At the very least, extend Domecq’s lobby ban and inform all staff members of the EDA that they should not be in contact with Mr. Domecq during this required period of time.

-

The EDA should, where necessary, invoke the option of forbidding senior staff from taking up certain positions after their term of office.

-

Set out criteria for when it will forbid such moves in future.

-

Consider bringing the EDA Staff Regulations in line with those of other EU agencies; and include the possibility of withholding an amount of the retirement pension when a member of staff acts in breach of the EDA staff regulations.

EDA does not budge until pressured by EU Ombudsman

In January 2021, Corporate Europe Observatory, Vredesactie and ENAAT wrote to the EDA raising our concerns with the approval of this job and asking the agency to bring its policies in line with the recommendations of the European Ombudsman to the European Banking Authority just a couple of months earlier on the handling of revolving door cases.

In its response to our correspondence, on 8 February 2021, the EDA refused to take any of these recommendations into consideration. The agency stated that it was “fully aware of the recommendations of the European Ombudsman in similar matters”, but that in this case the EDA believes that “the conditions set adequately protect the interests of the Agency and mitigate any potentially perceived conflict of interests.”

The EDA’s tone seems to have changed after the European Ombudsman launched an inquiry in February into the way the agency had handled the application by its former Chief Executive to take on senior positions at Airbus. Now the EDA has informed the Ombudsman that:

“based on the experience of handling the authorisation for Mr Domecq, EDA has initiated a more in-depth review of its current procedures in order to harness lessons learned and address any gaps identified in an effort to improve and ensure EDA’s approach in these cases is both compliant and effective. Some specific measures have been identified and are currently under discussion for implementation, and recommendations stemming from the EO’s inquiry will be reflected in this review.”

This certainly looks like a shift from the EDA’s previous public position. So far, however, there has been no public indication of what concrete changes the agency is considering.

Urgent and strict action required on revolving doors in EU agencies

This case emerged shortly after the very controversial approval by the European Banking Authority of its Director taking up employment with a banking lobby group. More recently, the European Investment Bank has authorised its former Vice-President to join the board of Spanish energy company Iberdrola, just three months after leaving office, in spite of financial links between the two. As with the EBA and EDA cases, this move was authorised by the EIB’s own Ethics Compliance Committee, with only some small restrictions stipulated.

Last year, Green MEP Sven Giegold wrote to all European agencies to inquire about their ethics rules. His findings were disappointing. According to the MEP, as far as could be ascertained, no agency had ever refused an employee’s authorisation request.

As the Domecq case illustrates, the ethics systems of the EU agencies needs to be significantly improved and strengthened, and a more uniform, strict, and reliable system must be developed.

Discussions to set up an Independent Ethics Body to provide guidance and oversee the implementation of ethics rules across the EU Institutions, including independent agencies, will be particularly important. The European Parliament is currently discussing a proposal to set up such a body open to the participation of all EU bodies and agencies. This is a good step forward.

Last week, Corporate Europe Observatory joined other civil society organisations to ask MEPs to make such a body independent, able to start its own inquiries and to implement its decision.

For the European Ombudsman, the “potential corrosive effect of unchecked ‘revolving doors’" is underestimated. Cases like the EDA’s approval of Domecq’s lobbying job at Airbus are a great example of how this plays out. The credibility of the EU takes a hit each time a new high level case hits the headlines and action must be taken urgently to finally ensure the Institutions take the negative impacts of revolving doors seriously and protect themselves accordingly.