From Facebook friends to lobby consultants

EU revolving door rules not fit for purpose

Several recent revolving door scandals show the weakness of EU staff rules on public officials taking up roles – particularly lobbying roles – in the private sector. These cases are allowed to happen due to a too lax approach to ethics rules: only one in two hundred applications for employment during the notification period or while on leave are rejected by the Commission services, and no enforcement is in place to check that former public officials comply with the rules to avoid conflicts of interest.

In May 2020, a recently departed Commission official shared on Twitter what she considered to be good news: she had been hired by Facebook to lead their EU lobbying team. Meanwhile a European Commission employee, worked on public policy for Vodafone while on leave; and the Brussels bubble reeled with the news that a former EU ambassador-turned-lobbyist was being investigated by the police.

These cases put a face on a wider EU institutional problem: current ethics rules are not slowing down the revolving door between the EU’s civil service and companies that lobby it. The Institutions seem unwilling to reject employment requests to take up employment while on leave or in the two years after departing. Official numbers released to Corporate Europe Observatory show that in 2019 out of all requests by Commission officials, a mere 0.62 per cent were rejected. New rules and better guidance on how to enforce them are urgent.

Facebook’s head lobbyist

On 6 May 2020, Aura Salla announced she was due to start a new job at Facebook’s EU lobby office as Public Policy Director, Head of EU Affairs. Within less than three months of leaving the Commission, Salla was to move to a role leading the team lobbying the EU institutions on behalf of one of the world’s biggest companies, not to mention one of the EU’s most active lobbyists.

Salla had spent over five years at the Commission working in high-level jobs, starting as a Cabinet Member for Vice-President Jyrki Katainen (who was responsible for Jobs, Growth, Investment and Competitiveness); moving on to the Commissioner’s advisory body, the European Political Strategy Centre; and finally ending up at at the advisory service Inspire, Debate, Engage and Accelerate Action (IDEA). The latter was set up to advise the European Commission on its core policy areas. Salla worked as an adviser at IDEA for over a year, responsible for cyber security, hybrid threats, disinformation, and election interference, EU defence, and Russia. All these topics rank high among Facebook’s policy interests.

She left the Commission in February 2020. A mere three months later she was leading Facebook’s lobby office.

As part of the EU Staff Regulations, officials seeking to take up new jobs after leaving the EU institutions must first seek authorisation (see Revolving door rules below). If the new role is related to the officials’ work for the previous three years and could lead to a conflict of interest, then the Commission can forbid it or approve it under conditions.

Salla first notified the European Commission of her desire to become Facebook’s head lobbyist on 31 March 2020. Yet even before the Commission had finished assessing the role, on 6 May 2020 Salla publicly announced the job, leading to media coverage and even congratulations from high-level Commission officials – including from the department responsible for regulating social media platforms, DG CNECT. The ethics rules seem to have been treated as a mere formality.

Revolving door rules

The employment of EU officials is guided by the EU Staff Regulations, a document that is co-negotiated by the Commission, Council, and Parliament.

Article 16 establishes the process for EU officials that want to take up a new job – whether paid or unpaid – within two years of leaving office. Within this period, officials need to seek authorisation from an Appointing Authority within their institution before accepting new employment.

If that activity is related to the work the official had undertaken in the previous three years and could lead to a conflict with the legitimate interests of the institutions, then the Appointing Authority can either forbid the official from taking that activity or approve it under certain conditions.

During the most recent reform of these rules in 2013, the European Parliament was particularly tough on the Commission, forcing it to add a lobbying ban for senior officials and an extra layer of transparency for these roles. However the implementation of these requirements, especially with regards to transparency, has been lacklustre.

The actual Commission ruling on whether Salla’s proposed new job was to be permitted only came two weeks later, on 13 May 2020. Sure enough Salla was allowed to become Facebook’s head EU lobbyist on the condition that she would not “have any professional contact with her former service (Inspire, Debate, Engage and Accelerate Action, IDEA) on behalf of Facebook or its companies for a period of 6 months. This included participating in events organised by IDEA,” and to not have professional contacts “aiming at lobbying or advocacy” towards the Commission related to the work she carried out during the last three years of service for a full year. Salla was also told to “refrain from exploiting insights of a confidential nature in policy, strategy or internal processes that she may have acquired in the line of service and that have not yet been public or are not commonly available in the public domain”.

These measures might seem comprehensive but overlook several aspects of the potential harms created by such revolving door moves, namely that EU officials take with themselves privileged know-how, access, and influence. The restrictions focus on Salla directly lobbying her former colleagues, but do not address at all the fact that she could well advise Facebook on who, how, and when to lobby.

The restriction for Salla to refrain from exploiting insights from her time at the Commission is particularly ridiculous as there is no way to enforce the prohibition against her using her insider knowledge and know-how to benefit her new employer, knowingly or otherwise. In a similar case, the European Ombudsman argued that not only was it impossible to enforce but that it could not be expected that such information would not influence the former official's decisions.

This case merited particular attention as Facebook has keen policy interests that overlap very closely with Salla’s work as a public official. Facebook has been in the cross-hairs of EU policy-makers for years, from the way it handles data protection, to the revelations of Cambridge Analytica and its role in election manipulation and the spread of disinformation. We expect that the coming years will be extra busy for its EU lobbying team, with discussions around fighting fake news and regulating platforms. For such a company, it is particularly helpful to be able to count on the help of such a high-profile Commission employee to help navigate these challenges.

Corporate Europe Observatory was told by a Facebook spokesperson that: “Aura Salla is carrying out her role as Head of EU Affairs at Facebook in strict compliance with the decision the European Commission took in this regard." Facebook did not comment on the concerns over conflicts of interest.

Facebook favours the revolving door

Hiring lobbyists via the revolving door is Facebook’s modus operandi. Facebook’s chief lobbyist Nick Clegg is a former Deputy Prime Minister of the United Kingdom. Salla’s own predecessors leading Facebook’s EU lobby office were a former MEP and a former Danish official.

The pattern is not restricted to top positions: at Facebook’s EU lobby office, out of seven lobbyists accredited by the European Parliament, four had a past in the EU institutions or permanent representations to the EU. One was recruited from DG CNECT and two were hired straight from the European Parliament to lobby the European Parliament. This is just a glimpse into the EU Affairs office as we don’t know the names of the others in their lobbying team without parliamentary passes.

The US provides more concrete data on Facebook's lobbyists: remarkably, 94 per cent of the 72 lobbyists working for Facebook (directly or via consultancies) have gone through the revolving door from public office Sidenote Data from OpenSecrets correct as of 19 October 2020 .

This is not a coincidence. Following the Cambridge Analytica scandal the company amped up its lobbying efforts and hired more lobbyists both in the US and in the EU. As Corporate Europe Observatory reported at the time, according to its own job adverts the company was looking for Brussels-based lobbyists “with both government/politics and industry experience” and required candidates to have “solid experience with working with politicians and government officials including those at the most senior levels”.

From regulator to regulated

Another problem at the Commission occurs when officials take unpaid temporary leave on personal grounds and then seek employment in the private sector, while keeping open the option to return to the Commission at a future point.

For example, in 2018 after 10 years in the European Commission, Reinald Krüger, then Head of Regulatory Coordination and Markets Unit at the Directorate-General for Communications Networks, Content and Technology, asked for a year's leave, as well as for authorisation to become Vodafone’s Group Public Policy Development Director. While at DG CNECT Krüger had been responsible for, among other things, regulating the telecoms market. He was then authorised to seamlessly move into a public policy job at a telecoms company.

Vodafone is a fairly major EU lobbyist with an annual lobby budget of €1,750,000 and a whopping 109 high-level meetings with the Commission since 2014. Its most popular lobbying targets include Krüger’s former bosses and colleagues at DG CNECT. Vodafone’s EU lobby declaration states the company is interested in “Information society, competition policy, consumer affairs, e-health, environment”.

According to the magazine Focus, Vodafone welcomed the new recruit with an internal memo congratulating itself on recruiting someone with “great experience” who “brings incredible knowledge and skills in the field of regulation”.

A representative of Vodafone told Corporate Europe Observatory that Krüger’s new job was unrelated to his tasks at the Commission and added that his role is “focused on policy development across Africa, Middle East, Asia and the Pacific. His role is not to represent Vodafone to the EU.”

However, this appears to conflict with previous reports from Netzpolitik which showed that Krüger had been in contact with former DG CNECT colleagues at several events: first at a Brussels based debate organised by Vodafone on the 'Internet of Things'; then at a Lisbon conference on 'The future of digital policy from the consumer's perspective'; and finally at a conference for European regulators in Riga. The latter seems particularly relevant as Krüger debated the issue of telecommunications markets, a discussion introduced by Krüger’s former boss at DG CNECT.

Krüger was also briefly a member of the Board of Directors of the Center for European Regulation - a think tank with many corporate members, including Vodafone. Just this year, Krüger has joined a panel discussion organised by the European telecoms lobby ETNO to discuss “The role of technology in the EU's new policy goals”.

Krüger’s new job at Vodafone while on leave from the Commission was authorised for one year under specific conditions. Krüger was told to:

-

“refrain from engaging in any activity or role which involves lobbying or advocacy vis-à-vis staff of the European Commission and which could lead to the existence or possibility of a conflict with the legitimate interests of the Institution”;

-

“not to deal in any way with files and matters directly linked to his work at the Commission to avoid the perception of any conflict of interest”;

-

"not [to] participate in meetings or have contacts of a professional nature with his former DG or service for a period of one year”.

It is important to note that there was no mechanism set in place to ensure that these restrictions were followed. In fact, it seems that they might have been broken at the events reported by Netzpolitik. In response, the Commission argued that there would only have been a problem had Krüger actually also organised these conferences, which seems like a narrow interpretation of the restrictions imposed. Yet the Commission has also refused to disclose the documents that would allow the journalists to identify whether or not Krüger had sent the invites. This refusal has led the European Ombudsman to classify the Commission's actions as maladministration.

As in the Salla case, Krüger was also told to “refrain from exploiting insights of confidential nature in policy, strategy or internal processes that he may have acquired in the line of service and that have not yet been public or are not commonly available in the public domain”. But this gets to the heart of the problem. This condition can never be reasonably implemented and is likely in direct contradiction to the rationale for employing him in the first place. As Vodafone itself has stated, it hired him because of his “incredible knowledge and skills in the field of regulation”.

Vodafone’s spokesperson told Corporate Europe Observatory that: “Mr Krüger is, and has always been, subject to the constraints set out in the Commission’s decision authorising him to do his current role.”

Even if Krüger did not have direct professional contacts with his former colleagues, there seems to be a clear conflict of interest in allowing an official on leave to become Public Policy Development Director at a company that is interested in the regulatory field for which he had been responsible. The restrictions imposed focused on limiting direct interactions with the former Head of Unit, but they do nothing to address the risk of his know-how and access indirectly helping Vodafone’s lobbying efforts.

Krüger is still at Vodafone and is still on leave from the Commission. When EU officials take up employment during personal leave, they have to seek re-authorisation every year for their employment. The Commission has approved the request in 2018 and again in 2019 and is now considering a third authorisation. If Krüger wished to do so, he could still return to the Commission after his time at Vodafone ends (see Rules governing personal leave below).

Rules governing personal leave

Personal leave for EU staff is governed by Article 40 of the EU Staff Regulations which states that officials can ask for unpaid leave for one year. Leave can though be extended to up to a maximum of 12 years.

During unpaid leave, officials can ask for authorisation to take up employment. Authorisation should not be granted for “an occupational activity, whether gainful or not, which involves lobbying or advocacy vis-à-vis his institution and which could lead to the existence or possibility of a conflict with the legitimate interests of the institution”.

Once leave expires, officials “must be reinstated” in the first post that is equivalent in grade and for which they are qualified.

From EU Ambassador to lobbyist for hire

Revolving door examples are not restricted to the Commission. The EU’s diplomatic service the European Union Externals Action Services (EEAS) recently faced public scrutiny over its approval for a former Ambassador to become a director of a lobby firm. This case came to light in January 2020 when German police, with the help of Belgian authorities, raided apartments and offices in Berlin, Munich, and Brussels. The police were investigating “allegations of espionage by secret agents” working on behalf of the Chinese Ministry of State Security which involved a former EU Ambassador-turned-lobbyist Sidenote Two other people were under investigation whose names never became public but reportedly worked for a separate lobby firm. . It quickly became apparent that one of the suspects was Gerhard Sabathil, a former EU Ambassador to South Korea and later an adviser who had left the EEAS in 2017 and immediately joined lobby firm EUTOP.

The firm is a significant lobby intermediary in European affairs, with 20 declared lobby clients and a substantial lobbying budget of over €2,500,000. EUTOP also has a questionable reputation, especially when it comes to hiding its work and using former politicians and officials to benefit its clients. For instance, German newspaper Der Spiegel has described its work as shrouded in secrecy and reported that “company founder Joos has a circle of mostly excellently paid employees from politics and business at his disposal”.

It is not clear if all clients are declared – there have been reports that EUTOP represents the German subsidiary of Huawei although this is not listed in the EU Transparency Register, and that in 2013 it lobbied the Commission on behalf of the Azerbaijani Government. EUTOP was also resistant to the EU’s lobby transparency register, belatedly joining it in 2016 and when it did, it created three entries covering its Brussels, Frankfurt, and Europe entities. It was only after a complaint from Corporate Europe Observatory to the Register Secretariat that EUTOP corrected its entry.

EUTOP's lawyers have told journalists that it is not involved in the investigation into alleged spying and Sabathil himself denies the accusations. According to Der Spiegel, the investigation is now at a standstill and the responsible federal prosecutors seem to be questioning some of the evidence that first led to the raids. Whatever the truth, there is another unresolved question: how is it that such a senior official of the EU’s foreign service was allowed to immediately become a managing director at a lobby firm where experiences from his time in public office would be an asset?

Corporate Europe Observatory was given the authorisation documents for Sabathil’s new jobs by the EEAS. These documents show that Sabathil notified the services in July 2017 of his intention to become a Managing Director at EUTOP Berlin. Sabathil’s application explained that his responsibilities were to manage the accounts of EUTOP’s clients, represent the lobby firm and network with national stakeholders in Germany, the Czech Republic, and Hungary. He also said that he would be involved in lobbying activities but only “on the national and regional level in Germany, Czech Republic and Hungary”.

Sabathil acknowledged that EUTOP’s affiliate companies lobbied EU institutions but in his view this did not cover “external action”. The EEAS seems to have disagreed as the documents indicate that they saw that EUTOP’s website listed trade agreements and trade policy as a key focus.

Despite all this, the job was still authorised. The EEAS told Sabathil that for one year he would be forbidden from lobbying the EEAS, the Commission, and the Council “on questions related to External Action, including trade and development cooperation”. Sabathil was also reminded of his confidentiality obligation and told that the authorisation was conditional on his work contract with EUTOP being amended to reflect this.

It seems clear that the EEAS saw potential risks with this role and they even took steps to try and prevent them by imposing conditions to the approval. Yet there was also not a single mechanism to ensure that any of these conditions were obeyed.

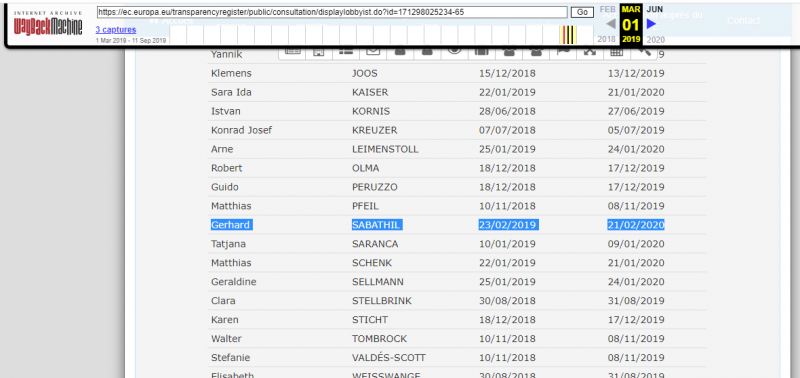

Even though Sabathil told the EEAS he would only be involved with lobbying at national and regional level, media reports describe him as having frequent engagements with Commission officials and Council Presidencies. In 2019 Sabathil added the role of Managing Director at EUTOP Brussels (in addition to the same role at EUTOP Berlin) and in February 2019 (date of accreditation checked on WaybackMachine), Sabathil got accreditation to lobby the EU Parliament. This was beyond the 12 months lobbying ban (which is standard in such cases) but still within the two year period when senior officials need to seek authorisation before taking on any new role.

We have sought Sabathil’s comments via EUTOP and his lawyer but have received no reply.

Green MEP Daniel Freund believes that for the Staff Regulations to have been properly implemented, Sabathil should have been forbidden from taking any EUTOP roles for two years following his departure from the EEAS. After news regarding the investigation broke in January 2020, and under intense media pressure, the EEAS announced it would start an investigation on possible wrongdoing by the former ambassador but no news has followed. As far as Corporate Europe Observatory is aware, the criminal investigation is ongoing.

Ethics fail: only 0.62% revolving door moves rejected

These three cases – Salla, Krüger, Sabathil – have differing contexts but they show how the EU Staff Regulations are not being properly implemented. As far as can be seen, all three officials asked for authorisation from their institution, their roles were assessed and approved with restrictions. In none of these cases has a mechanism for monitoring or enforcing compliance been created.

For Corporate Europe Observatory all three cases should have been rejected for a specific period, at least as long as the requirement to seek authorisation for new roles (two years). This would be fully in line with the current EU Staff Regulations (Article 16 and Article 40) which foresee the possibility of rejecting a role when it is related to the work the official had led in their past three years of service and which could create a “conflict with the legitimate interests of the institutions”.

In 2019 the Commission services approved 363 requests for post-public office employment from officials, and it rejected just 3. When it came to requests to take up outside employment during personal leave, it approved 594 requests and rejected 3.

Yet there seems to be a reluctance to fully implement the EU Staff Regulations by considering a rejection if a risk of conflict of interests is identified and serious. Corporate Europe Observatory has asked the Commission how often it rejects employment requests. According to the department of Human Resources, in 2019 the Commission services approved 363 requests for post-public office employment from officials, and it rejected just 3. When it came to requests to take up outside employment during personal leave, it approved 594 requests and rejected 3.

That translates into an overall rejection rate of only 0.62 per cent. Obviously we don’t have access to the justification of each assessment and many of these moves are likely harmless and could be approved. But when we compare the miniscule rejection rate to the many problematic authorisations we know about, we see we have an institutional praxis that accepts the risk of conflicts of interest and reputational damage, rather than fully implementing the EU Staff Regulations.

Individual cases of concern create specific problems: the potential for conflicts of interests, or for specific companies to gain privileged influence and know-how, to take just two. But the revolving doors phenomenon gains another dimension when it becomes systemic, as it erodes the boundaries between public and corporate interest and damages the integrity of policy-making, as well as undermining public trust as a whole.

Farkas controversy exposes holes in ethics system

This unwillingness to reject even cases of concern echoes the recent controversy at the European Banking Authority and its authorisation of then-Executive Director Adam Farkas to leave and start a new job at the financial lobby group, the Association for Financial Markets in Europe (AFME). This case led to a complaint to the European Ombudsman by the coalition ChangeFinance (which includes Corporate Europe Observatory). The Ombudsman eventually found that the EBA’s handling of this case constituted maladministration and, that as per the Staff Regulations, the job ought to have been entirely rejected.

Interestingly, the Farkas controversy also lifted the veil on the reasoning behind approving these cases. When the EBA sought to justify its decision, it pointed to a little known Commission decision taken under the guidance of then Commissioner Oettinger and approved in June 2018. The Commission Decision C(2018) 4048) clarifies how the Commission services should interpret the EU Staff Regulations and implement them. In this document the Commission recommends that the services should define “an appropriate balance between the need to ensure integrity through temporary prohibitions and restrictions and the need to respect the former staff member’s fundamental right to engage in work and to pursue a freely chosen or accepted occupation”.

It seems the way this plays out, is that when considering an authorisation, the option of prohibiting a job move is not seriously considered. That was certainly the case with the European Banking Authority. It should also be noted that temporarily forbidding a high level official from taking up a specific job, such as one that creates conflicts of interest or that includes lobbying, does not constitute an attack on the right to ‘engage in work’. In many cases it is a legitimate move to protect the integrity of the EU institution and is explicitly included in the EU Staff Regulations.

The process drawn up by the Commission Decision also relies on a system of restrictions but does not set up any monitoring or enforcement system, either at the individual case level or institutional level. By approving this decision, the Commission has effectively gutted the EU Staff Regulations. It also sets a bad example for other EU bodies such as the EBA.

One could also point to the bad example set by EU political leaders in cases like former President Barroso taking up a job at Goldman Sachs International, or Commissioner Oettinger setting up his own consultancy while in office and being allowed to start activity within one year of leaving.

This decision is, of course, not the only reason behind the poor enforcement of the rules. One could also point to the bad example set by EU political leaders in cases like former President Barroso taking up a job at Goldman Sachs International, or Commissioner Oettinger setting up his own consultancy while in office and being allowed to start activity within one year of leaving. These high level examples define a culture where revolving doors moves are seen as a normal part of the career progression.

Last month Corporate Europe Observatory joined other NGOs to write to the Commission to take stock of the Farkas case and the Ombudsman rulings and act to close the revolving door. Specifically, we asked the Commission to:

-

Enforce the rules on post-public employment within the Commission and in all EU agencies.

-

Sharpen the rules concerned with revolving doors.

-

Make sure that strong rules on conflict of interest and revolving doors are implemented across all EU institutions.

-

Harmonise the rules so that different ethics documents do not contradict each other. Meanwhile, the Commission should make sure that EU Staff Regulations are fully complied with.

-

Consult the public when creating an independent body to supervise and enforce the rules on revolving doors.

-

Create a culture of integrity by fostering staff knowledge and understanding of ethics rules.

All these measures are needed; otherwise the scandals and controversies will continue as the revolving door keeps spinning.