Why Europe can’t break free from the gas lobby

- By Pascoe Sabido, originally appeared in Social Europe

The invasion of Ukraine has exposed Europe’s dependency on Russian oil and gas. Its imports are directly funding Putin’s war efforts, to the tune of €20 billion in March alone. The EU’s response – driven by a mix of concerns over energy insecurity, price rises and domestic political instability, and the need to defang the Russian war machine – has been to double-down on gas from other sources and promote other fossil fuel industry-proposed alternatives. This is despite the fact that the IPCC’s latest report says we need to slash fossil fuel use as it’s “now or never” to stave off climate disaster.

So how did the EU come to depend not just on Russian gas, but all fossil gas? This is a consequence of how the fossil fuel industry has successfully captured EU decision-making. This was evident in 2014, when Russia occupied Crimea, and continues today with the powerful gas lobby shaping Europe’s response to the Ukraine crisis.

As a result of this ‘gastastrophe’ of corporate capture, the EU will continue to fuel conflict (if not in Ukraine then in Yemen and elsewhere), continue to fuel climate chaos, and continue to fail the millions who are facing a growing cost of living crisis.

2014: Ditch gas or double down?

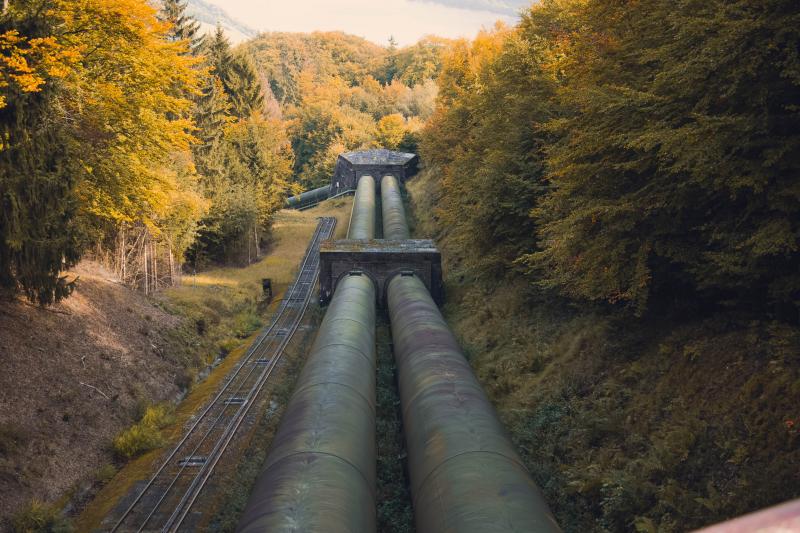

Russia’s annexation of Crimea in 2014 focused EU minds on reducing reliance on Russian gas. But rather than ramping up wind, wave, and solar energy, or energy efficiency – measures that would tackle climate change, fuel poverty, and gas dependency – the EU doubled down on gas from other equally dubious sources. Political and financial backing was given to pipelines from Azerbaijan and liquified natural gas (LNG) terminals which could ship-in fracked gas from the US.

This is the direct result of the co-dependent relationship between the European Commission and the gas lobby. A remarkable example is how the same companies who build and operate gas pipelines and LNG terminals, like Italy’s Snam, France’s GRTgaz, Belgium’s Fluxys, Spain’s Enagás, and the UK’s National Grid, were legally incorporated into EU policy-making via their membership of the European Network of Transmission System Operators for Gas (ENTSO-G), a group created by EU legislation.

The role of ENTSO-G is to predict future gas use and propose infrastructure projects to meet it, which its members then build. There couldn’t be a more obvious conflict of interest. Unsurprisingly, the group consistently over-estimated future gas demand; as a result between 2013-2020 the EU spent €4.5 billion on 44 new gas infrastructure projects, with 90 per cent of the money going to ENTSO-G members.

Thus, despite the urgency of the climate crisis, the EU remained dependent on a fossil gas, whose carbon footprint can be as bad as coal. Thanks to falling domestic production and increased LNG import capacity, Russian gas filled the gap by piping and shipping its gas. By 2021 Russian imports had reached 40% of the EU’s total gas consumption, an increase of almost half compared to 2013. Not only was this a mockery of climate goals, but by not moving away from gas, the EU rendered itself far more vulnerable to changes in global gas prices, particularly LNG spot prices, which caused skyrocketing energy prices in autumn 2021 even before the invasion of Ukraine.

2022: The story repeats itself?

The EU is once again trying to reduce its dependency on Russian gas; its latest RePowerEU communiqué aims to reduce demand by two-thirds by the end of 2022, and to stop all fossil fuel imports – coal and oil included – by 2027. But the proposed solutions have the fingerprints of the gas lobby all over them.

A core plank of RePowerEU, which will be fully fleshed out by 18 May, is to source oil and gas from beyond Russia. For example from other repressive regimes, such as Azerbaijan, Qatar, and Saudi Arabia, which executed 81 people days before British Prime Minister Boris Johnson visited Riyadh to ask for an increase in production.

The push for diversification is accompanied by a massive push for new gas infrastructure, both from industry and the European Commission. We’re facing half a dozen new LNG terminals in Germany and the revival of MidCat, a shelved pipeline from Portugal to Spain and then France. Yet new research shows increased support for rooftop solar and energy efficiency could reduce Russian gas imports by two-thirds in the next three years, with existing infrastructure easily covering the remainder.

RePowerEU also sets huge targets for gas lobby techno-fixes like hydrogen and biomethane, which are a climate disaster but highly profitable for industry. The communiqué talks about an extra 15 billion tonnes of ‘green’ hydrogen from renewable electricity by 2030, both domestic and imported, which is more than double the EU’s current target. But where will the renewable electricity come from when the EU is already missing its renewable energy targets? Today 97% of Europe’s hydrogen is made from fossil gas rather than renewable electricity, and Shell, Equinor, and other gas producers are confident that fossil hydrogen will remain a permanent fixture. They openly admit there will not be enough renewable electricity to produce the quantities of hydrogen being spoken about, but are using the appeal of green hydrogen (made from renewables), and the broader push for an EU-wide hydrogen market, as a trojan horse for their own fossil hydrogen. Despite this, the European Commission is pushing forward regardless, thanks to crafting its response to the Ukraine invasion hand in hand with the gas lobby.

Meanwhile 2030 targets for biomethane have also been doubled. The EU and industry claim it will come from agricultural or municipal waste, but producing high quality biomethane is easier and cheaper to produce from crops, likely competing with food, as we saw in the 2000s when high biofuel targets saw spikes in food prices and widespread hunger. Given the pandemic and war are hitting food prices, not just fuel, this solution is deeply short-sighted.

While the EU’s communiqué covers energy efficiency, compared to previous drafts this has been seriously weakened. According to sources close to the drafting process, neither the European Commission nor EU governments are relying on energy efficiency to reduce dependency on gas as it is “not concrete enough” compared to new sources.

Shifting from cheap Russian gas to expensive and volatile LNG while building expensive new infrastructure is only going to exacerbate the cost of living crisis, yet the social impact of the plan is not discussed. The opportunity to tackle it via energy efficiency, such as a mass insulation programme that could have trained up and employed thousands while lowering people’s bills, has been passed over. That’s also a missed opportunity for useful climate action.

Even the positive proposal of a windfall tax on Big Energy, supported by some national governments, is limited in scope, fearing it could ‘de-incentivise’ energy companies from investing in renewable energy. It couldn’t be clearer how the EU is putting the interests of the gas industry before the increasing numbers of energy poor, and climate action, because of the long-standing and incestuous relationship between the gas industry and decision-makers.

The risk of sleeping with the gas industry

The RePowerEU communiqué is itself evidence of the corporate capture of EU policy making by the gas industry, but since the invasion there have been more brazenly public examples. The President of the European Commission, Ursula Von der Leyen, openly tweeted about her meetings on reducing gas demand with the European Roundtable of Industrialists, a CEO-level lobby group whose members include TotalEnergies, BP, and E.On. As a result of that meeting, she publicly announced she was going to “Set a group of industry experts to help reduce our dependency [on Russian gas]”.

At the national level, CEO of Italian oil and gas major Eni has been on a world tour alongside Foreign Minister di Maio to secure new gas supplies from countries such as Algeria, Azerbaijan, and Angola. Similarly, Germany’s new Green climate and economics minister has been in Qatar signing a deal for LNG.

Corporate capture means EU energy policy is being crafted with and for the gas industry, threatening decades of continued fossil fuel lock-in. If we want to end our reliance on gas, Russian or otherwise, then we need to end the relationship between the fossil fuel industry and decision-makers, cutting fossil fuel interests out of our political system. In short we need fossil free politics.