Stay always informed

Interested in our articles? Get the latest information and analysis straight to your email. Sign up for our newsletter.

As the EU works to regulate per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS), decision-makers would do well to tune out the voice of the chemicals industry, just as they did with Big Tobacco and fossil fuels.

This article was written by Vicky Cann and originally appeared in Euractiv.

The EU is proposing to phase out PFAS, the toxic ‘forever chemicals’ found in everything from frying pans to waterproof coats. But PFAS producers and their industry customers are fighting back.

PFAS, per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances, are man-made chemicals which are hard-wearing and persistent meaning they resist degradation, hence their nickname ‘forever chemicals’.

As more and more evidence comes to light from scientists and the Forever Pollution project about the extent of PFAS contamination in our bodies and environments in Europe and around the world, the costs of trying to deal with these toxic chemicals, even if it were possible, is being counted in the billions, even trillions.

At the same time, more and more evidence is emerging about when the industry first knew that these chemicals were deeply problematic and what they did, or more precisely didn’t do, as a result.

Recent academic analysis of previously secret documents from major PFAS-producers DuPont and 3M shows that companies knew PFAS were “highly toxic when inhaled and moderately toxic when ingested” by 1970, 40 years before the public health community.

The companies used several strategies to influence science and regulation, including “suppressing unfavourable research and distorting public discourse”.

The parallels between the PFAS industry and the denial tactics of the Big Tobacco and fossil fuel industries are clear, and now we can see the legacy of that approach. Today in the Netherlands it is recommended not to eat fruit or vegetables coming from gardens within a one kilometre radius of a DuPont PFAS factory.

Now the regulation of ‘forever chemicals’ is firmly on the EU political agenda, with a proposal for an EU-wide PFAS ban on the manufacture, sale, and use of PFAS. And the industry has wised up.

Desperate to take the heat off their products, PFAS polluters are going out of their way to recognise public concern about ‘forever chemicals’, while simultaneously trying to persuade decision-makers that they are willing to sort it out themselves.

Having established this narrative, the PFAS public relations operation moves into phase two, with a much more ‘business as usual’ approach i.e.: to argue that a producer or user’s own PFAS are in a special class and therefore need special treatment, such as an opt-out to the ban.

Apparently the five or 12 year temporary opt-outs already included in the EU proposal are not enough.

Instead the new game in town is to attach your PFAS product to an EU strategic priority, whether it is the remnants of Ursula von der Leyen’s Green Deal or the EU Chips Act which aims to boost European competitiveness in the field of semiconductors.

The industry’s hyperbolic insistence that PFAS are critical to these sectors denies how regulation can be a key driver to finding sustainable alternatives. After all, replacements for PFAS are being found for various supply chains, and many consumer-focused companies are demanding a comprehensive ban.

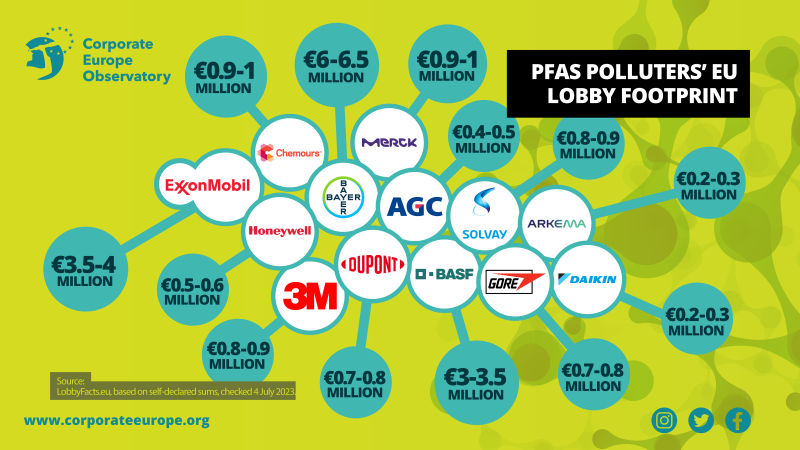

Nonetheless, PFAS polluters are largely sticking to these strategies – presenting themselves as reasonable, concerned actors, and then demanding a special opt-out for their products. And following these chemical producers and their corporate clients into battle are a legion of bespoke PFAS lobby groups, PR consultancies, and law firms.

EU officials must be feeling the heat, even at this early stage of the PFAS policy-making process.

But it does not have to be this way.

Governments around the world no longer allow tobacco companies to lobby on public health matters: the public interest in eliminating smoking is diametrically opposed to the commercial interests of cigarette companies.

Decision-makers are also increasingly being asked to reject the lobby overtures of the fossil fuel industry when it comes to decision-making about the climate crisis.

So why should decision-makers keep listening to the chemicals industry when it comes to regulating PFAS and other high-risk substances and pesticides? Industry is throwing the kitchen sink at influencing the consultation process on the proposed EU PFAS ban.

But once it is ended, industry should be kept well away from the decision-making process that follows.

PFAS are the new tobacco, and we must learn from the firewall strategies in place to restrict the tobacco industry. Commercial interests must not be allowed to pollute public interest decision-making to regulate ‘forever chemicals’.