PFAS are forever?

How the chemical industry is fighting back against regulation

Corporate Europe Observatory uncovers the story of how the toxics industry is fighting back against the upcoming regulation of PFAS or 'forever chemicals', which are found in everything from frying pans to food packaging. Using access to documents requests and LobbyFacts data we show how chemical companies paint themselves as reasonable, concerned actors, whilst at the same time privately pushing hard for exemptions for their own PFAS products, and warning in dramatic terms of the economic fallout of banning them. Meanwhile the real catastrophe – the impacts on human health and the environment – as well as the costs of clean up, continue apace.

Introduction

Every day it seems like there’s a new media story about the pollution legacy of PFAS (so-called ‘forever chemicals’) in our bodies and environments. And every day new legal suits are filed against the producers of PFAS by affected communities or workers. Legislators around the world, including in the EU, are taking action to tackle these groups of chemicals. But the fight-back of the toxics industry is underway against efforts to ban groups of PFAS, not least in the EU. Below Corporate Europe Observatory explores the key PFAS polluters and industry lobbies, and some of the strategies they are using. The PFAS industry is trying to avoid the PR disaster of being compared to Big Tobacco and Big Oil and their denial tactics. Instead the toxics lobby is acknowledging the public concern about PFAS pollution. But probe more carefully and it is clear that industry is trying to carve out exemptions to the banning of its toxic products. This is a cynical ploy because, just like Big Tobacco and Big Oil, the industry knew the truth about its products decades ago and chose to do nothing.

Why has it taken forever to regulate ‘forever chemicals’?

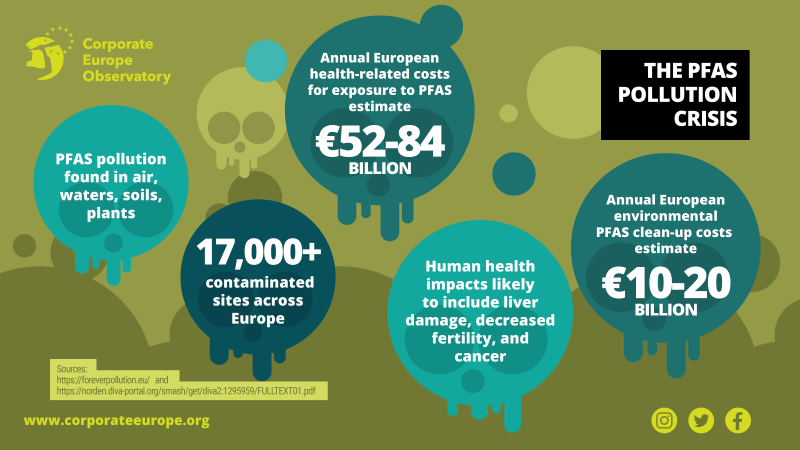

From non-stick frying pans to waterproof coats, from cosmetics to electronic chips in your phone or laptop, per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) are everywhere. This large class of thousands of man-made chemicals contain carbon-fluorine bonds which are one of the strongest in organic chemistry. They are hard-wearing and persistent, meaning they resist degradation, hence their nickname ‘forever chemicals’. These chemicals are also sometimes very mobile and there are now at least 17,000 confirmed PFAS-contaminated sites across Europe, with a further 21,000 presumed contamination sites. Sidenote For more information on the science of PFAS, check out the European Environmental Bureau’s webpage https://eeb.org/work-areas/industry-health/pfas/, CHEMTrust’s Ban PFAS manifesto https://www.banpfasmanifesto.org/en/, and HEAL’s PFAS pollution campaign https://www.env-health.org/banpfas/

The companies producing PFAS knew for decades about the toxicity of these chemicals, but they chose to do nothing about it. Recent academic analysis of previously secret documents from DuPont and 3M shows that companies knew PFAS were “highly toxic when inhaled and moderately toxic when ingested” by 1970, 40 years before the public health community. The analysis further notes that the industry used several strategies also common to tobacco, pharma, and other industries to influence science and regulation, including “suppressing unfavorable research and distorting public discourse”.

According to documents analysed by the news show Zembla, DuPont knew 30 years ago that it was seriously contaminating the groundwater under the Dordrecht plant in the Netherlands and in the surrounding area with large quantities of toxic and carcinogenic PFAS. SidenoteYou can read the response to Zembla by Chemours, DuPont’s successor company, here: https://www.chemours.com/en/about-chemours/global-reach/dordrecht/dordrecht-nieuws/reactie-chemours-op-uitzending-van-zembla-dd-15-juni In 2022 it was recommended not to eat vegetables or fruit coming from gardens within a one kilometre radius of this PFAS factory.

Today, communities and governments are starting to come to terms with decades of toxic PFAS pollution. While the impacts are not easy to quantify, some health-related costs for exposure to PFAS across Europe have been estimated at €52-84 billion per year, for potential consequences such as liver damage, decreased fertility, and cancer. €10-20 billion is a plausible figure for European environmental clean-up costs. And the monetary figures are quite aside from the suffering caused. Meanwhile at a global level, Swedish NGO ChemSec estimates annual global PFAS costs at a massive €16 trillion when remediation and water clean-up are added in, but even that could well be an underestimate.

Despite this PFAS pollution crisis, the regulation of these chemicals remains decidedly patchy. The Stockholm Convention on persistent organic pollutants has contributed towards the phasing out of some PFAS. But very regrettably corporations have just substituted these chemicals with other PFAS, or substances that break down to PFAS. Today, many, many others remain in use, including some fluorinated gases (F-gases), fluoropolymers, perfluoropolyethers, and fluorotelomer substances which are often found in water-, oil- and stain-repellents as well as fire-fighting foams.

The lesson is surely that future PFAS regulations must be fully comprehensive and must avoid substitutions with other problematic substances. 125 NGOs have been demanding a ban on all PFAS in consumer products by 2025 and a complete ban by 2030.

A new regulatory effort is now underway with a proposal from five countries (Denmark, Germany, the Netherlands, Norway, and Sweden) to introduce an EU-wide universal PFAS (uPFAS) restriction to ban the manufacture, sale, and use of PFAS, of which about 10,000 substances have been identified so far. The proposal suggests an 18 month transition period for all PFAS uses to be phased out with a 5 or 12 year “derogation” for some uses where substitutes are not currently available. Such opt-outs already foreseen include the medical, food production, energy cell, and extractive sectors.

The EU Chemicals Agency (ECHA) is currently conducting a detailed consultation on the uPFAS proposal; eventually ECHA will provide its scientific opinion on the proposal to the European Commission which will then consult with the European Parliament and the Council. A uPFAS restriction could be in place by 2025, but in practice the lobby battle could well mean that it takes much longer.

But speed is of the essence. Unless action is taken, another 4.4 million tonnes of PFAS will end up in the environment over the next 30 years.

PFAS polluters’ EU lobby footprint

Corporate Europe Observatory recently profiled the Big Toxics lobby operating in Brussels, exposing how they are one of the biggest, if not the biggest, sector active in Brussels. But who are the producers of PFAS?

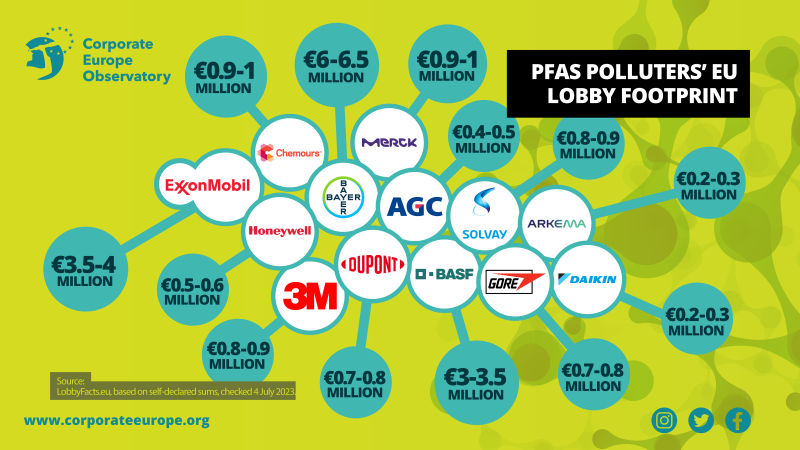

Chemsec has identified the 12 largest producers of PFAS in the world, accounting for a majority of production. These (in alphabetical order) are: 3M, AGC, Archroma, ARKEMA, BASF, Sidenote For an indepth study of BASF, check out: https://corporateeurope.org/en/chemical-romance-politicians-basf Bayer, Chemours, Daikin, Dongyue, Honeywell, Merck, and Solvay.

Using LobbyFacts’ data from the EU lobby transparency register, Corporate Europe Observatory has calculated that these chemical producers have a self-declared total EU lobby spend (on all topics) of between €13.7 million and €15.5 million in the past year for which they have provided figures, with 53 European Parliament access passes currently held. Not all of the 12 largest producers have joined the EU lobby register: Archroma and Dongyue have not but, at least in the case of the former, still appear to be actively lobbying the EU on PFAS (see below).

Other PFAS producers or users are DuPont, ExxonMobil, Gujarat, Synthomer, and Gore, who are all members of a significant EU lobby group on PFAS (FPP4EU, see below). While only 3 of these 5 are registered in the EU lobby register, their inclusion means that the major PFAS polluter EU lobby footprint (based on self-declared annual figures of the 13 registered companies above) grows to between €18.6 million and €21.1 million, with 72 lobbyists, and 59 Parliament passes. If even a proportion of this firepower is directed towards the uPFAS proposal, it is formidable. All figures are available in this spreadsheet.

Boosting the PFAS industry's lobby firepower

Beyond these chemical companies there are new, bespoke lobby groups being set up to concentrate corporate firepower on proposals to regulate PFAS.

The EU chemical lobby trade association CEFIC – which regularly tops the LobbyFacts list of biggest declared spenders on lobbying – set up 'FluoroProducts and PFAS for Europe' or FPP4EU in March 2021, bringing together 14 of the PFAS producers or users mentioned above. FPP4EU says that its members produce, import, and use over 300 PFAS. FPP4EU calls for “time unlimited derogation on PFAS used in industrial settings”, that the proposal should address “primary and secondary financial impacts”, and “take into account the drive for a competitive, resilient and sustainable Europe”. In other words, the lobby representing 14 of the biggest PFAS industry players wants an unending opt-out from the ban for industrial uses of PFAS and a focus on economic interests when regulating these toxic chemicals. Information secured via an access to documents request indicates that FPP4EU has met with DG Grow twice (in October 2022 and December 2022), including a meeting with FPP4EU’s “Collaboration Platform” which included “many industry stakeholders” and representatives from member states.

PlasticsEurope, another of Brussels’ Big Toxic lobbies, has also set up a group to work specifically on PFAS. The Fluoropolymers Product Group (FPG) was created in 2022 and a majority of the companies listed above are members. It argues that a total ban on fluoropolymers would not be proportionate and that “a general derogation for fluoropolymers” ie a time-unlimited opt-out should be provided in the proposal. The FPG spoke at the FPP4EU 'Collaboration Platform' event with DG Grow (presentation) to promote the idea that there should be continued manufacture and use of fluoropolymers and a “Voluntary Industry Initiative” to deal with “situations of concern”. Such voluntary initiatives are a well-known industry lobby tactic to divert attention away from binding regulation. A DG Grow official also attended an FPG event following the publication of the uPFAS proposal in February 2023 “to hear the reactions of industry stakeholders”. [Email.]

In the US similar industry lobby groups are also being set up. The Sustainable PFAS Action Network (SPAN) was launched in 2022 and brings together corporate lobbies from the semi-conductor and aerospace industries for example, and argues against banning “all PFAS compounds”, although it is not clear that such a ban is proposed anywhere. Honeywell and Daikin are members.

But the PFAS lobby is much more than just the biggest producers and their bespoke industry advocates. There is the wider chemical industry lobby (such as Eli Lilly), plus other industries which use PFAS in their products or manufacturing processes further down the supply chain (such as EPEE, the refrigeration and air conditioning lobby, which is active on F-gases), and wider business lobbies (such as the American Chamber of Commerce or AmCham, which is actively lobbying to demand broader opt-outs in the uPFAS proposal). And that’s not to mention the lobby firms and law firms acting on industry’s behalf (see below).

This article is just considering the lobby footprint of the key PFAS industry actors at the EU level. But the current uPFAS proposal was developed by five member states and member states will play an important role in finalising the restriction. And lobbying already seems intense within member states too.

The Flemish environment minister Zuhal Demir recently told the Parliament that, on the uPFAS dossier: "I also share the concern that we need to see that no delaying tactics are invoked, because I also note that the lobbying machine - this has been something of the past three months - has increased enormously. In fact, it is going from bad to worse, I think. I will give my own account that we as a cabinet were contacted by a major lobbying firm working with PFAS. We turned that down. Then an intermediary was brought in. We also said to that intermediary, "No, those are the formal procedures. You have to follow those." They were not satisfied with that either. Then they approached individual people from my cabinet on social media and so on. Allow me to say that I do find that fairly aggressive ... Surely in the last three or four months that lobbying has been huge."

Of the 17 PFAS producers and users listed above, 11 are also in the German lobby register and have a combined self-declared lobby spend of up to €9 million in Germany in the most recent year for which figures are available, on all topics, with 94 lobbyists. Figures are available in this spreadsheet. If these figures are replicated across other member states, the PFAS industry lobby footprint becomes even greater.

Taking the heat off PFAS...

The six month ECHA consultation on the uPFAS restriction which started in March 2023 appears to be the current focus of PFAS polluters’ influencing efforts. Indeed, PlasticsEurope was refused a one-to-one meeting with DG Grow in the Spring because, as the official noted: “At this moment, I do not foresee to have specific meetings with industry representatives on the UPFAS dossier because each time the message will be the same: not on our desk; please submit information in ECHA’s consultation.” (Email.)

While the consultation is dry and technical, it also provides plenty of opportunities for the PFAS lobby to have wider political influence on the debate.

In April 2023 UK-based PR company Commetric published communications advice for companies producing PFAS or using them in their products or industrial processes. Its central point is that companies with a PFAS PR problem should learn lessons from Big Tobacco and Big Oil: to paraphrase, their advice is: don’t deny the PFAS problem, acknowledge it, and set out how your company is part of the solution.

Indeed this kind of approach seems to be prevalent in Brussels, with companies and other corporate actors going out of their way to apparently recognise the growing public concern about PFAS and their willingness to work with regulators to sort it out. This strategy aims to take the heat off PFAS, while creating the impression that industry is a reasonable and legitimate actor which can be relied upon to do the right thing.

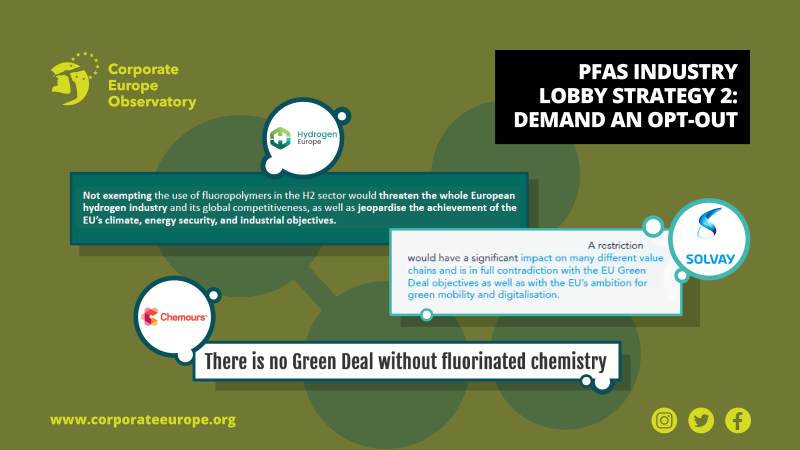

… And then argue for an opt-out

Having established this narrative, the PFAS PR operation moves onto phase two ie to argue that a producer or user’s own PFAS are in a special class and therefore need special treatment, such as an opt-out to the ban. The current uPFAS proposal already makes concessions to various sectors offering them temporary opt-outs for 5 or 12 years, but for the PFAS industry, this is not enough. And their PR operation is using some key EU strategic priorities to make the case against the uPFAS restriction.

“There is no Green Deal without fluorinated chemistry”, we are told. Or, “A restriction… is in full contradiction… with the EU’s ambition for green mobility and digitalisation”, says Solvay. “Not exempting the use of fluoropolymers in the hydrogen SidenoteHyped demand for green hydrogen (made from renewable energy) is problematic. It ends up supporting dirty hydrogen (during the supposed transition to ‘cleaner’ hydrogen) and represents a huge grab of clean energy, including from the global south, when that electricity could meet local development needs and climate targets instead. sector would … jeopardise the achievement of the EU’s climate, energy security, and industrial objectives”, says another.

But will this hyperbolic insistence that PFAS are critical to the green economy really work? We know that regulation, including substance bans, can be a key driver to push companies to find more sustainable alternatives, and a derogation of 12 years is a lengthy period to make that transition. As ChemSec points out, some companies are already finding replacements for PFAS in the green energy, refrigerant, semi-conductor, and water-repellency industries.

We have been here before. When the EU worked on the original REACH regulation SidenoteREACH – the EU’s flagship chemicals regulation from 2007 – is the registration, evaluation, authorisation and restriction of chemicals. It aims to improve the protection of human health and the environment through the better and earlier identification of the intrinsic properties of chemical substances. https://ec.europa.eu/environment/chemicals/reach/reach_en.htm a couple of decades ago, the chemicals industry scaremongered that the proposal would “de-industrialise Europe”. They were on the wrong side of history then and little has changed since.

Nonetheless, PFAS polluters are largely sticking to these strategies – presenting themselves as reasonable, concerned actors, and then demanding a special opt-out for their products – and are being supported in these efforts by various lobby, PR, and law firms.

Wider PFAS allies

Chemours is one of the biggest producers of fluoropolymers with 12 per cent of global production and 64 PFAS chemicals on ChemSec’s SIN (substitute it now) list of hazardous substances. According to the New York Times, Chemours was spun-off from DuPont in 2015 so as to “assume the liabilities” from some of DuPont’s PFAS, explosives, and asbestos operations. But the NYT argues that: “The transactions that created Chemours and reinvented DuPont laid the groundwork for a blame-shifting exercise that has made it difficult for regulators and others to hold anyone accountable for decades of contamination”. SidenoteTo find out more about DuPont’s history of producing PFAS and denying their consequences, watch Dark Waters: https://www.imdb.com/title/tt9071322/

Chemours is where notorious products such as Teflon now sit. Little wonder, then, that the company is the most prominent actor in the fight-back against the uPFAS restriction. Chemours has defended both fluoropolymers and F-gases via sponsored messages in Politico newsletters, in a tour of various European business newspapers to apparently tell “Chemours' side of the story”, and a placed article in Euractiv. Chemours secured a meeting with Environment Commissioner Virginijus Sinkevičius in March 2023 to discuss the uPFAS restriction.

Beyond this, Chemours has set up a ‘Customer Advocacy Portal’ to encourage its downstream customers (businesses which use Chemours’ PFAS in their own products or processes) to defend them in the ongoing ECHA consultation on the proposed PFAS restriction. With YouTube videos, submission guides, and background briefings, Chemours is hammering home its PFAS messaging. Chemours is apparently aided in this mission by FTI Consulting, the second biggest lobby consultancy firm in Brussels, with some of the documents in the portal including the Fluoropolymer Advocacy Toolkit and other briefings apparently authored by FTI or its staff.

According to the EU lobby register, in 2022, FTI also received up to €400,000 from Honeywell, including for work on PFAS. In 2020 FTI was criticised for driving influence campaigns for Big Oil.

Alongside FTI, Chemours has also contracted other lobby consultancies Rud Pedersen (up to €400,000) and EU Focus Group (up to €600,000) for lobby work in 2022.

Chemours is not the only member of the PFAS lobby helping with submissions to the ECHA consultation. CEFIC’s PFAS sector group FPP4EU has provided advice to its members about how to respond to the consultation. In 2022 Brussels’ biggest lobby firm Fleishman-Hillard received €1 million from CEFIC including for work on “Environmental & energy policy incl. REACH, classification & labelling, sustainable food systems, F-Gases”. It is not clear if FPP4EU is specifically included in Fleishman-Hillard’s ongoing contract with CEFIC, but in 2023 it also reports working for other PFAS producers, DuPont and Arkema. Fleishman-Hillard accompanied Arkema to its lobby meeting with DG Grow in January 2023 to discuss PFAS, and one of its specific products. [January 2023 minutes.]

Other lobby firms are working for members of the PFAS industry. In 2022 Burson Cohn & Wolfe had contracts with ExxonMobil (up to €600,000), 3M (up to €300,000), and PlasticsEurope including its FPG group (up to €200,000). In fact, each of the top 6 lobby consultancy firms in Brussels (according to LobbyFacts) have at least 2 of the biggest PFAS industry players among their clients.

In March 2023 lobby firm Kreab helped facilitate a meeting with DG Grow for PFAS producer Archroma to present its arguments for an opt-out for its PFAS products. [Email.] This corporate lobbying appears pretty secretive: firstly Archroma is not registered in the lobby register even though Kreab has an obligation to make sure that all its clients are registered. Kreab declared receiving up to €200,000 from Archroma in 2022 and the PFAS producer also appears on Kreab’s list of 2023 clients. Corporate Europe Observatory has made a complaint to the EU lobby register about this. (UPDATE: the lobby register secretariat has now replied to our complaint, indicating that Archroma has now joined the lobby register.) Secondly, DG Grow refused to release an additional Archroma document related to the meeting because the company refused it permission to do so. Corporate Europe Observatory has made an appeal on this point. In 2022 Kreab also worked for Daikin (up to €400,000) and AGC (up to €200,000), including on PFAS issues.

Outside of the top 6 biggest Brussels’ lobby firms, others are also active. For example, FIPRA organised a debate on PFAS in December 2022 which included industry and an NGO speaker; DG Grow also attended. Two of the three industry speakers – COCIR (lobby representing semi-conductor industry) and EFPIA (the pharma lobby) – were FIPRA lobby clients from the wider PFAS supply chain. [Meeting summary.]

Law firms smell blood

Alongside lobby firms, law firms have a lot of skin in the PFAS game. Several well-known law firms already represent ‘forever chemicals’ producers in the growing number of lawsuits as more evidence comes to light about the impacts of these toxic chemicals. Further legal action could be on the way.

Hogan Lovells has acted for PFAS-producer 3M in an environmental law suit in California as a city council sought to recover costs to restore its city’s water supply after being contaminated with chemicals. Hogan Lovells has also commissioned a report from ToxStrategies, a US-based 'scientific consulting firm' which says that it aims to “address the scientific, technical, and regulatory challenges confronting our clients”. The Hogan Lovells-commissioned report on PFAS 'mixtures' includes several industry-friendly arguments which could be helpful for future lobbying or legal challenges on PFAS. ToxStrategies has previously produced research into PFAS which was “supported” by Chemours and has also presented "study findings in meetings with regulators, including public meetings, on behalf of Chemours".

Another law firm, Mayer Brown, which has also represented 3M and says that it works on “PFAS litigation”, has published a briefing on the proposed uPFAS restriction calling it “draconian” and setting out “how we can help”. Mayer Brown calls for lobbying of the European Commission and ECHA, but already talks up the possibility of a legal challenge in the future. It cites its legal case, on behalf of chemical producers (including Chemours) against the restriction of another (non-PFAS) substance, titanium dioxide, after a regulatory lobby battle. This legal challenge led to the annulment of the restriction which was a big win for industry, but a bitter blow to anyone wanting robust regulation of “possible carcinogens to humans” such as titanium dioxide. Both the European Commission and the French Government have now appealed the annulment of the titanium dioxide restriction.

Meanwhile law firm Steptoe says it has the largest dedicated EU chemical and environment regulatory practice in Brussels. Last month Steptoe organised a conference in Brussels on “chemicals and sustainability”, including PFAS, with speakers from CEFIC, Eurometaux, Total, PFAS producer Solvay, and a DG Grow speaker. Its “client alert” policy briefings, particularly the overview of the PFAS restriction raises several “legal concerns” about the proposed uPFAS restriction. Steptoe is affiliated to both AmCham EU and the UK trade association the Chemical Industries Association.

All in all, there are strong indications that law firms in Brussels and beyond are joining the PFAS industry’s fight-back, readying for the upcoming lobby battle ‒ and potential legal fights.

We can’t trust industry

Here we are in 2023 and the PFAS industry wants us to trust them. They know best and, they tell us, they fully support a ‘green transition’.

But let’s be clear: companies knew about the risks of PFAS for decades and did nothing to stop it. This is why we are now facing a massive pollution crisis, the burden of which will largely fall on tax-payers to clean up or at least manage.

Today one company, 3M, is alone among the major PFAS polluters in saying it will exit PFAS production by the end of 2025. The reality of this remains to be seen, but its extensive PFAS legacy means that its legal liabilities are colossal, and presumably it can see the writing on the wall for these toxic substances.

But the rest of the industry looks set to try to battle on, to one degree or another. They are arguing for opt-outs from the proposed PFAS ban, instead of opting out of PFAS production for good. By doing this they continue to insist that the burden of PFAS should fall on people and planet, and not on those who created the problem in the first place. By presenting themselves as apparently reasonable and responsible corporate actors, the PFAS industry is trying to sow the seeds of doubt in the minds of EU decision-makers about how far the uPFAS restriction should go, especially on the number and length of the opt-outs.

We know that we can’t trust Big Tobacco when it comes to public health lobbying. We know that we can’t trust the fossil fuel industry when it comes to tackling the climate emergency. So why should decision-makers keep listening to the toxics industry when it comes to regulating PFAS and other high-risk chemicals and pesticides? Industry has the opportunity to respond to the ECHA consultation, but it then needs to be kept well away from the decision-making process that follows. Commercial interests must not be allowed to pollute public interest decision-making to regulate ‘forever chemicals’.