Stay always informed

Interested in our articles? Get the latest information and analysis straight to your email. Sign up for our newsletter.

‘Stop deindustrialisation!’ is the latest hyperbole from the Verband der Chemischen Industrie (German chemical-industry association) in pushing back against more robust regulation of toxic chemicals. A major lobby domestically and on the European level, one of its tactics is to shift the focus from the huge impacts of these substances on our health and the environment—and scaremonger over threatened ‘competitiveness’ instead.

This op ed first appeared on Social Europe.

As well as demanding action to tackle high energy prices, VCI has in its sights the European Union’s most important legislation in this arena, REACH (Registration, Evaluation, Authorisation and Restriction of Chemicals), which it demands the EU institutions ‘avoid tightening’. Its also pushes to ‘stem the tide of new regulation’ and ‘prevent blanket bans’ of toxic chemicals.

We have been here before. Twenty years ago, the European Chemical Industry Council (CEFIC) used exactly the same rhetoric - called out at the time by Corporate Europe Observatory - when it opposed the introduction of the original REACH rules. These would purportedly ‘de-industrialise Europe’ and result in two million job losses. In fact, since 2002 the EU’s export of chemicals has grown on average by a remarkable 6.7 per cent annually.

But REACH is no longer fit for purpose. The European Green Deal promised action towards a toxic-free environment, and the European Commission committed itself to revising REACH, since the current rules are failing to get toxic chemicals off the market at anything like the pace needed to resolve the pollution crisis.

This is indeed urgent. European citizens are exposed to ‘alarmingly high levels of chemical substances’, linked to cancer, infertility, obesity and asthma while also contributing to the collapse of insect, bird and mammal populations. Yet, three years on, the commission has failed to produce its proposal to revise REACH. It is not only delayed but expected to be diluted in ambition too.

Right now, the fate of the revision hangs in the balance. How could a progressive policy aimed at tackling serious health and environmental issues, alongside a large number of other key pieces of the Green Deal agenda on pesticides and biodiversity, have become so vulnerable to industry pressure?

The VCI, whose members include BASF and Bayer, has been among the loudest voices pleading with German and EU policy-makers to stop new EU chemicals rules. And the pressure will certainly be on the chancellor, Olaf Scholz, when he hosts industry, trade unions and politicians at a chemicals summit on Wednesday.

After all, VCI is the fifth biggest lobbyist in Germany, declaring an annual budget of almost €9 million to influence domestic politicians and 64 active lobbyists. At the EU level, VCI is the fourth biggest trade association lobbying in Brussels (CEFIC is the biggest). Beyond this, Lobbypedia describes VCI as one of the ‘largest party donors’ in Germany, with €5.7 million in donations to political parties across the spectrum between 2000 and 2021.

German politicians have been prominent in opposing the revision of REACH—a call which has been picked up by the right-wing European People’s Party and heard at the highest levels. Last week the commission president, Ursula von der Leyen, failed to mention the REACH revision in her State of the EU speech. Even the environment commissioner, Virginijus Sinkevičius, is sounding doubtful about its fate, telling the European Parliament this month that he hoped the proposal would see the light of day—‘if the ambition is there’.

A key plank of industry’s rhetoric is that regulation is too ‘burdensome’ to cope with. That narrative has seemingly hit home with right-wing politicians. Reframing environmental regulation as a ‘burden’ is a common yet misleading tactic of the toxic-chemicals lobby: the real burden is the huge impact on human health associated with the manufacture, sale and use of such substances.

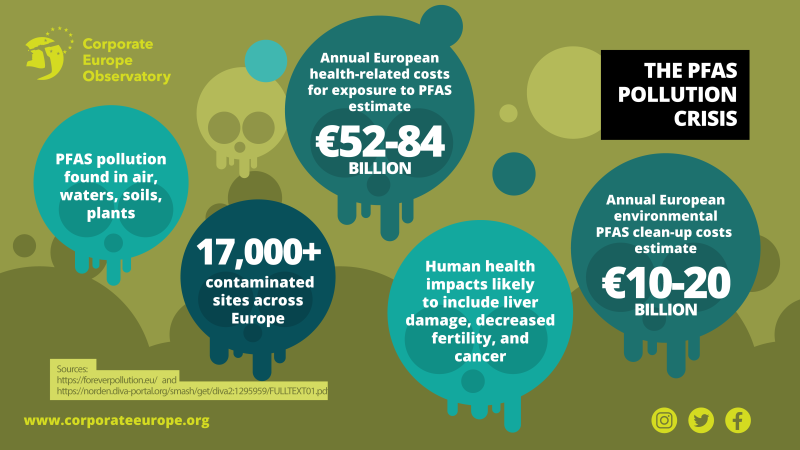

Estimating only some of the health-related costs of Europe-wide exposure specifically to per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS)—also known as ‘forever chemicals’—in a single year gives a tally of €52-84 billion. While the huge health and environmental consequences of toxic chemicals represent an ‘externality’ not showing up on any company’s balance sheet, these costs are all too real.

BASF and Bayer are among the top 12 global producers of PFAS, as well as leading sellers of the world’s most toxic and controversial pesticides. Between them, the two industrial giants produce 156 chemicals which, according to ChemSec, are ‘substances of very high concern’ which should be phased out.

Von der Leyen’s commission is about to decide whether to maintain its 2020 promise of a robust proposal to reform REACH, to regulate toxic chemicals better, or cave in to industry’s demands. This makes the timing of Scholz’ chemicals summit particularly concerning.

Having entertained the chemicals industry this week, will he flex his political muscle on its behalf by putting through a quiet call to the Berlaymont, as previous chancellors have done on behalf of other German industrial interests? Or will he remind industry that tighter environmental rules are not only in the public interest but ultimately can drive industrial efficiencies and a transition to sustainable products?

Politics is about taking tough decisions. For chemicals regulation, this means standing up to the power of the Big Toxics, to protect our health and that of our soils and waters. European citizens will be hoping Von der Leyen and Scholz meet that challenge.